Newark Museum: 106 Years Ahead of the Curve

by Ulysses Grant Dietz, Chief Curator

The Newark Museum’s vast and diverse collections showcase a broad range of works that explore the past, inspire the present, and provide a glimpse into the future. With eighty galleries in a campus comprising six buildings, including the 1885 Ballantine House, the Newark Museum holds a unique place in the history of American museums. Newark’s selection for the Winter Antiques Show’s annual Loan Exhibition at the Park Avenue Armory in January introduces the museum to many who may be unfamiliar with the institution and our collections.

Founded in 1909 by museum pioneer John Cotton Dana, the museum is the largest in the state of New Jersey and ranks in the top thirty nationally in terms of the size of its collections. The Museum’s holdings of over 130,000 objects embrace American painting and sculpture; European and American decorative arts; the arts of global Africa; Native America and the Pacific; Asian art; and art of the ancient Mediterranean. In addition, the museum is steward of the largest natural science collection in the state.

The birthplace of the Newark Museum was the Newark Free Public Library on Washington Park, where a museum committee was established in 1902. The library’s fourth floor was arranged as a spacious suite of galleries, divided between installations of art and displays of natural history specimens. In 1909, the Newark Museum Association was formally incorporated, inspired by Dana’s vision of a museum that was not just an ornament to the thriving industrial city whose library he directed, but an institution that would be useful to the people who lived there.

His founding trustees included a department store magnate (Louis Bamberger), a varnish king (Franklin Murphy, who would also serve as New Jersey’s governor), and an art gallery owner (Frederick Keer Jr.). Aware of the great museums in Boston, Saint Louis, Chicago, and of course, in Manhattan and Brooklyn, only about ten miles from Newark, Dana worried that these institutions were intended largely as places where the social elite displayed their treasures. Dana, the museum’s director from 1909 to 1929, imagined his museum doing for visual learning what libraries did for book learning.

The small number of large municipal art museums that existed in the United States in 1909 all focused on the primacy of painting and sculpture in the arts, and (even worse from Dana’s point of view), the central importance of European painting and sculpture. He believed that people interacted with art through ordinary objects and that his museum would be a place where the “art of today” would be given the spotlight.

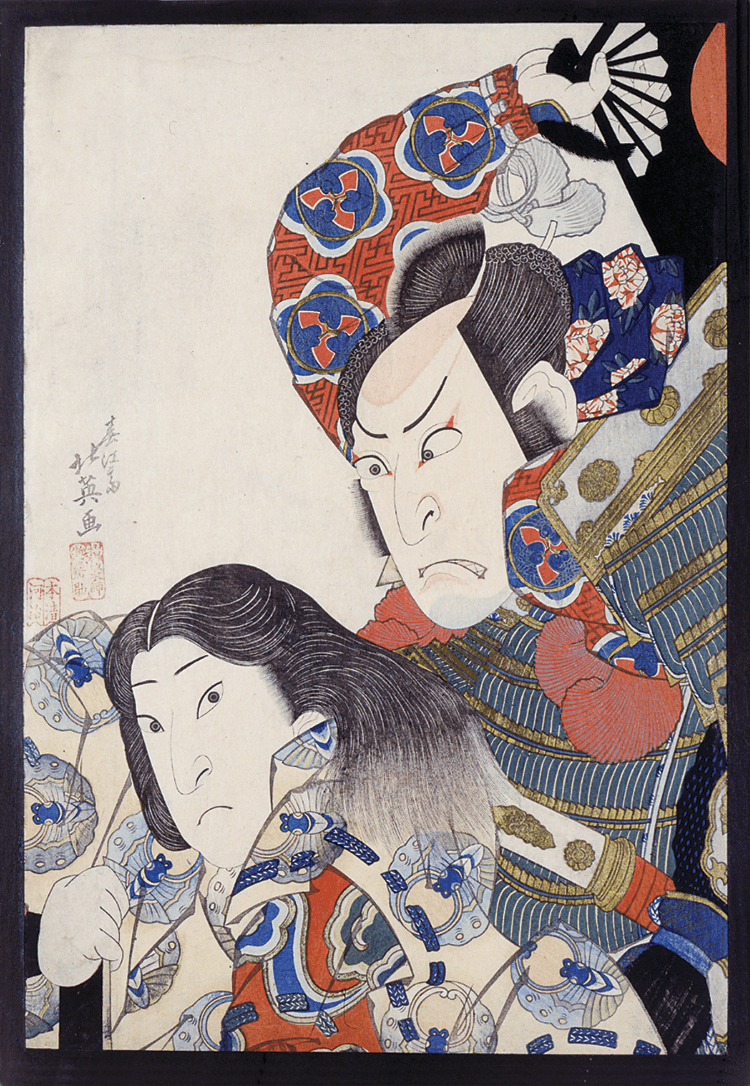

This philosophical background helps to explain the Newark Museum’s unorthodox founding purchase—made with a one-time appropriation of $10,000 from the City in the summer of 1909. The trustees used the grant to purchase the collection of Japanese and Chinese art, several thousand pieces, gathered by Newark pharmacist George T. Rockwell. The bulk of this enormous assemblage was decorative arts of the Edo and Meiji periods (Fig. 1). Newark can boast one of the finest collections of netsuke, inro, and ojime in the country, as well as one of the best ukiyo-e print collections.

The museum’s collection of Tibetan art started in 1911 with an exhibition of 150 works acquired through a medical missionary to Tibet, Dr. Albert Shelton. The fame of the Tibetan holdings, while deserved, has somewhat overshadowed the equally fine Japanese and Chinese holdings, which includes pieces found in few other museums (Fig. 2*). The Kangxi (1661–1722) meiping of seven horses included in the Winter Antiques Show display is a remarkable tour de force of Chinese enameled porcelain, inspired by scroll paintings of horses of the same period. Today the Asian art collection stands at nearly 30,000 objects and covers every part of Asia. Masterworks from Tibet, China, Japan, Burma, and India have been included in the Winter Antiques Show loan exhibition.

Western decorative arts were the next major theme in the fledgling museum’s history. The department was born when the museum acquired dozens of pieces of ceramic art in association with the 1910 exhibition Modern American Pottery. Dana believed that well designed, handcrafted pottery had the advantage over painting and sculpture because middle-class people could actually afford to buy it for their own homes. The ceramics collection expanded between 1910 and 1914 to include modern American, English, German, and Austrian pottery and porcelain. Dana organized a display of Cincinnati’s Rookwood Pottery in 1912, and in 1914, purchased seven pieces for the museum’s growing collection (Fig. 3*).

The Museum’s interest in modern design and craft is well documented in the objects gathered both during John Cotton Dana’s tenure as director and after. Newark was the first American museum to acquire Secessionist glass (three pieces purchased in 1912 from an exhibition of German applied arts); the first to acquire glass by René Lalique (three pieces purchased in 1913 from Haviland and Company), and the first to acquire silver by Georg Jensen (purchased from Jensen’s agent in 1922 by Louis Bamberger for the museum). In 1929, just after Dana’s death, the museum hosted a large exhibition of international ceramics and glass, in conjunction with two Newark department stores, from which it added French and Scandinavian pieces to its collection (Fig. 4*).

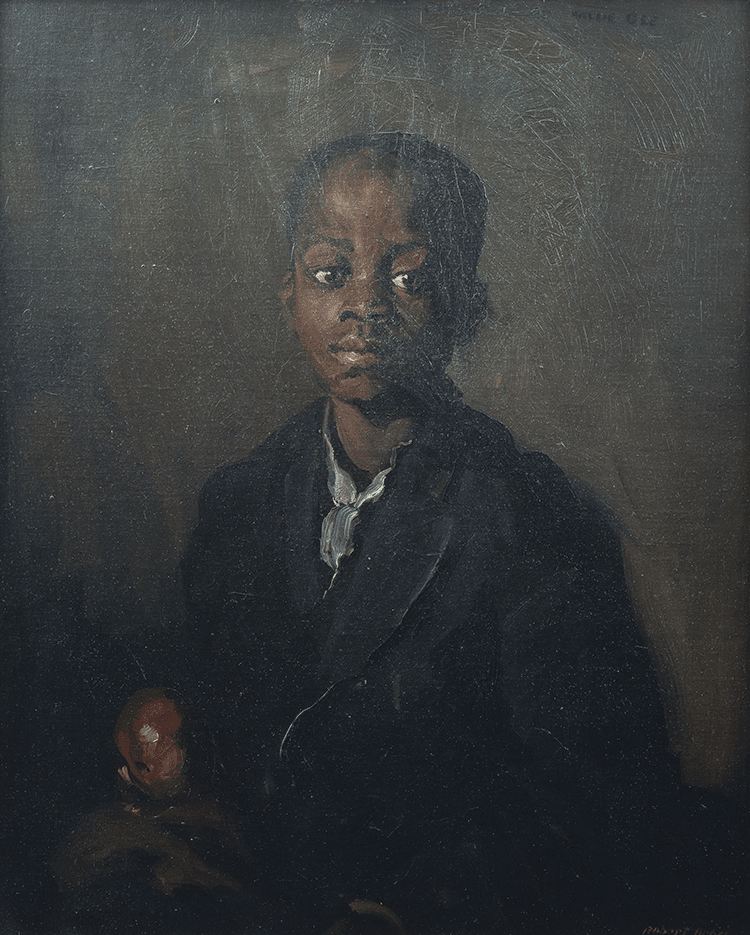

In spite of Dana’s resistance to the hegemony of “fine” art, at least two of his trustees, Franklin Murphy and Felix Fuld, were advocates for painting and sculpture. Fuld was Louis Bamberger’s business partner in the Newark department store, and was married to Bamberger’s sister Caroline. The Fulds became important patrons of the museum’s modern art collection. In 1909, while one of the New York museums had yet embraced what was seen by many at the time as radical art, the Newark Museum hosted one of the first exhibitions of works by “The Eight,” organized by the Macbeth Gallery. The first painting the museum ever purchased was by the modernist by Ernest Lawson in 1910; it was also the first Lawson acquired by a museum in the Northeast. The museum also gave Max Weber a one-man show in 1912, the first by a living artist in an American museum. The museum’s support of American modern artists was so influential that in 1925 Robert Henri donated his 1904 masterwork, Willie Gee, after Newark purchased another portrait by him that same year (Fig. 5*). The most important acquisition of Newark’s early decades was undoubtedly Joseph Stella’s monumental five-panel Voice of the City of New York Interpreted (1920–1922) (Fig. 6). When no other museum in the country would commit to all five of these large canvases, Caroline Bamberger Fuld and her husband’s legacy won the day.

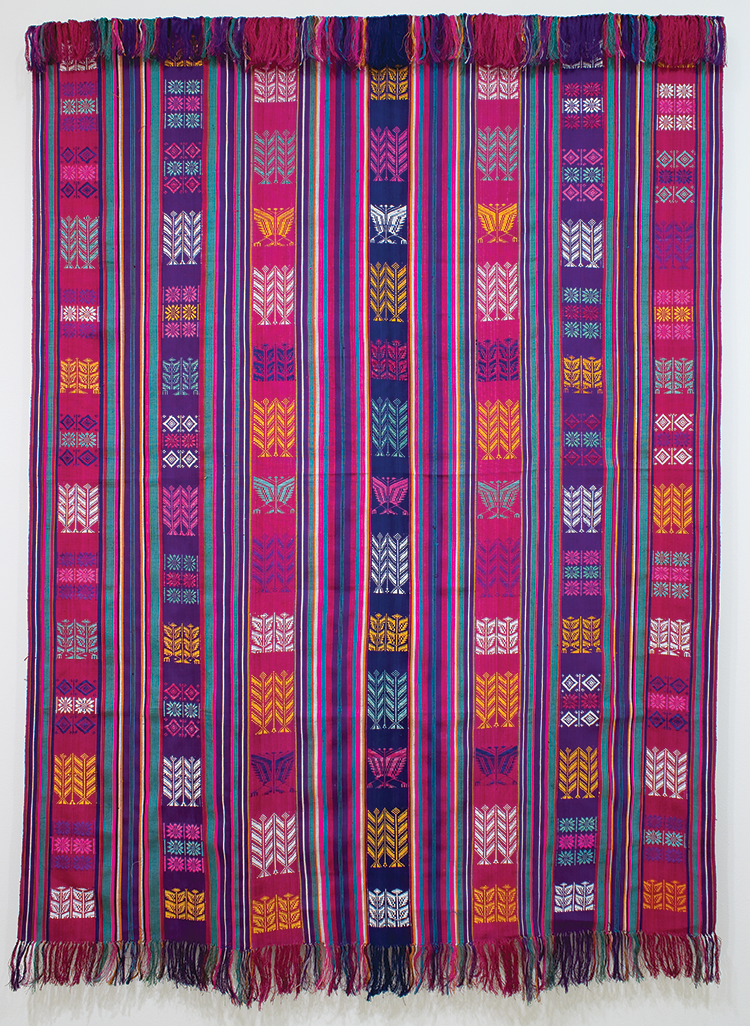

One of the forward-thinking interpretive positions that the Newark Museum took was to present works not rooted in Western European notions of art. Art of the Americas (Native North and South America) was collected and displayed as early as 1912, and the first pieces of African art (two pieces of Zulu beadwork) were acquired in 1917. The museum displayed objects that, while very different from each other and representing widely diverse cultures, were seen as expressing the same motivating interest in color, design, craft, surface, and form. One of Dana’s particular favorites was textiles, because, like ceramics, these were domestic, and relied on both craft and design principles for their aesthetic success (Fig. 7). The museum did a large exhibition on New Jersey’s textile industries in 1916, and began collecting American quilts in 1918. As a result of its wide-ranging focus, it enjoys one of the country’s most comprehensive holdings of African art (Fig. 8), representing the whole of the continent from the Mediterranean coast to the Cape of Good Hope. Today, the museum is in the vanguard of museums collecting the contemporary art of global Africa.

It was not until a major gift in 1924 that the museum began to acquire antiquities from Egypt, Greece, Rome, and the early Islamic world. The incorporation of antiquities into the overall collecting program was logical because it was fairly straightforward to link this to both early Asian material and to the sculpture, ceramics, glass, textiles and metalwork of the modern day. In 1950, a New Jersey collector, Eugene Schaefer, left thousands of ancient objects to the museum, including one of the finest holdings of ancient Egyptian, Roman, and early Islamic glass in the nation (Fig. 9).

Since its founding, the Newark Museum has only expanded twice, and today still faces the challenge of showcasing a collection that has far outgrown its campus. After the first stand-alone building was completed in 1926, the museum went on to acquire an adjacent insurance company to its north on Washington Park—which included the 1885 Ballantine House—in 1937, for additional offices and classrooms. In 1980, with the acquisition of an unused 1912 YWCA building to the south, the museum hired Princeton-based architect Michael Graves to transform this eclectic group of structures into a coherent exhibition complex. The Ballantine House, no longer necessary for administrative use, but in remarkably intact condition, was converted to gallery space in two waves, the first for the national bicentennial in 1976, and the second in 1994. House & Home, the exhibition of decorative arts within the Ballantine House was the first art museum installation to contextualize decorative arts objects and to focus on the meaning of home in America. Funded by the Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Collections Accessibility Initiative, the Ballantine House continues to exemplify the Newark Museum’s ongoing effort to stay ahead of the curve and to offer its visitors a starting place on a journey in visual learning (Fig. 10).

Ulysses Grant Dietz is chief curator and curator of decorative arts at Newark Museum.

This article was originally published in the Anniversary 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.