Preserving New York: The City's Historic Landmarks Law Turns Fifty

- Fig. 2: The Brokaw Mansion, 1 East 79th Street; built 1887–1890, Rose and Stone, architects. The public outcry and scathing press coverage relating to the threat to and actual demolition of this significant building in the mid-1960s were some of the key factors that led Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. to sign landmarks legislation into law on April 19, 1965. Image circa 1910–1915. Courtesy, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (LC-DIG-ggbain-15066).

On April 19, 1965, New York’s Mayor Robert F. Wagner, Jr. signed the New York City Landmarks Law, over a half-century in the making, which finally provided legal protection for the city’s treasured buildings, neighborhoods, and special places (Fig. 1). By the time the law was passed scores of architecturally significant buildings had been lost to the wrecking ball, among them the Brokaw Mansion (Figs. 2, 3), the Savoy-Plaza Hotel (Fig. 4), the Produce Exchange (Fig. 5) and Schwab House (Fig. 6). Battle weary from decades of losses, New York’s preservation community rejoiced at finally winning the right to protect the city’s landmarks.

At the heart of the law was the creation of a Landmarks Preservation Commission, an eleven-member board to be made up of a minimum of three architects, a historian, a city planner or landscape architect, a realtor, and at least one resident of Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island. While the law’s passage could not bring back the scores of demolished buildings that held so much of New York’s history, it was the legal mechanism needed to counter developers and planners wanting to build a city of the future at the expense of its past.1

Often believed to have been passed in response to public outrage at the 1963 destruction of Pennsylvania Station (Figs.7a, b), the Landmarks Law actually has its origins in the mid-nineteenth century when a fascination with historic sites generated public interest in saving important landmarks grew and led to the formation of large numbers of patriotic societies—among them, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union, the first national preservation organization and the oldest women's patriotic society in the United States.

The city’s most influential activist in the nineteenth century, Andrew Haswell Green (1820–1903), founded the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society in 1895. The first organized preservation lobby, and an umbrella organization for the nascent movement, the ASHPS attracted such influential supporters as John D. Rockefeller Jr. and J. Pierpont Morgan. Early twentieth-century preservation battles included saving high visibility sites such as the Morris-Jumel Mansion in upper Manhattan and historic Fraunces Tavern, one of the city’s oldest buildings. In 1913, the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society teamed with the Municipal Art Society and other civic advocates in an effort to stem the growth of the visual pollution caused by outdoor advertising along one of the city’s emerging grand promenades, Fifth Avenue. Their combined efforts were thwarted for lack of regulatory legislation.

Perhaps the most effective preservation advocate was New York civic activist, lawyer, and one-time president of the Municipal Art Society, Albert Sprague Bard (1866–1963). His Bard Act, passed in 1956, gave municipalities the right to create laws to protect their landmarks. Although he did not live to see the Landmarks Law signed, the Bard Act was the legal prerequisite for its creation.

- Fig. 5: Produce Exchange, Broadway at Bowling Green; built 1884; George B. Post, architect. Architectural historian Talbot F. Hamlin, who called the Produce Exchange the best of Post’s work, vehemently objected to the building’s 1957 demolition, asking whether New Yorkers were “such slaves to economic pressures that they can have no say in what they see, no power to preserve what they love?” Nevertheless, the building was replaced with 2 Broadway, which was derided by critics. Nathan Silver, in his 1967 book Lost New York, wrote: “The produce exchange, one of the best buildings in New York, was replaced…by one of the worst.” Image ca. 1904. Courtesy, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (LC-D401-17551).

- Fig. 6: Charles M. Schwab House, Riverside Drive between West 73rd and West 74th Streets; built 1902–1906, Maurice Hébert, architect. c. 1910–20; This extravagant, seventy-five room mansion was one of the grandest residences ever built in Manhattan. Schwab went bankrupt in the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and bequeathed the house to New York City as an official residence for the city’s mayors in 1939. However, reform-minded Mayor Fiorello La Guardia refused to live there and it was eventually demolished in 1948 and replaced with an apartment building; Image ca. 1910–1920. Courtesy, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (LC-DIG-det-4a24599).

- Fig. 7a, b: The Waiting Room and exterior of Pennsylvania Station between 31st and 34th Streets and 7th and 8th Avenues; built 1910, McKim, Mead & White, architects. Image ca. 1911; Courtesy, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Waiting Room: [LC-DIG-ds-04712 (digital file from original); LC-USZ62-68672 [b/w film copy neg.] Exterior: LC-DIG-det-4a23398.

- Fig. 9: 2 Columbus Circle; built 1964, Edward Durell Stone, architect. Built by A&P heir Huntington Hartford as the Gallery of Modern Art, this distinctive building was first put forward for landmark protection in 1996. But despite a heated advocacy battle that enlisted many notable architects, writers, artists, and preservation organizations, 2 Columbus Circle was never designated and it’s facades were modified when the Museum of Arts and Design took ownership. Image, 2010. Courtesy of Renate O’Flaherty, Wikimedia Commons.

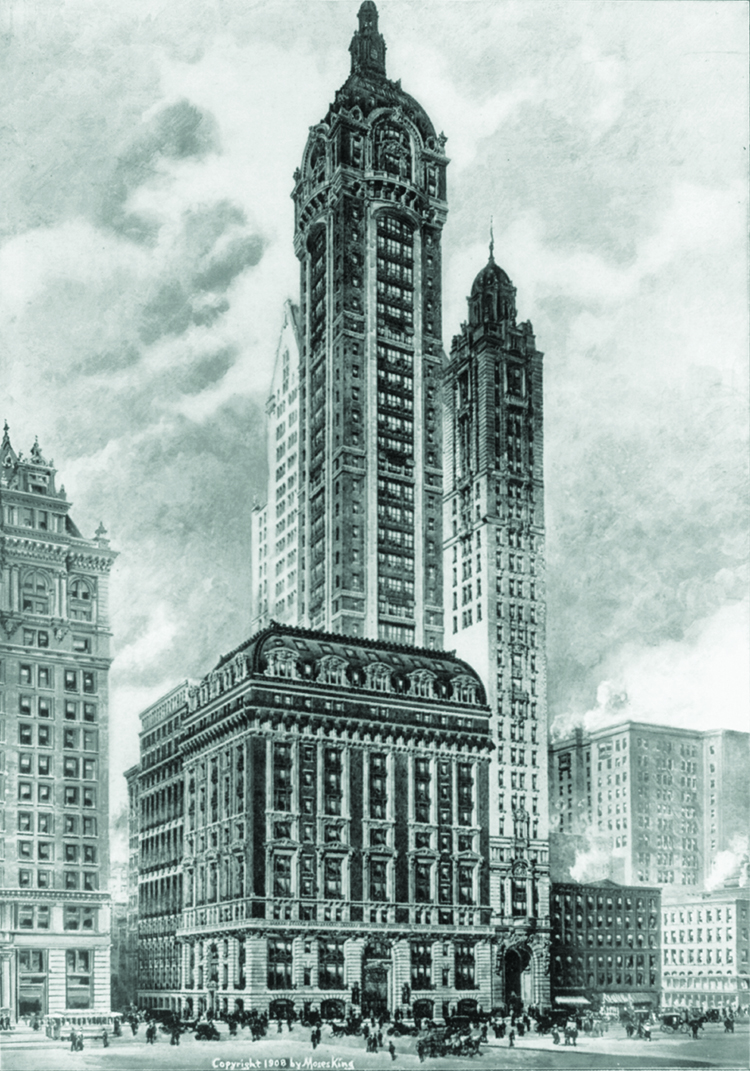

Though during the past fifty years the Landmarks Preservation Commission has designated nearly 1,400 individually significant buildings and 111 historic districts, preservation activist Anthony C. Wood in his book Preserving New York: Winning the Right to Protect a City’s Landmarks (2007) argues that the Landmarks Law needs constant monitoring if it is to continue to be effective.2 He reminds us that “The story of New York’s Landmarks Law is not that of some top-down government mandate for preservation but rather an example of if the people lead, the leaders will follow. The law was the product of an engaged and enraged citizenry demanding, after decades of tragic losses, a formal process for saving the city’s architectural, historical, and cultural sites and neighborhoods…But even with it, we have still lost remarkable sites such as the Singer Building (Fig. 8) (lost in 1967), and the façade of 2 Columbus Circle (Fig. 9) (refaced: 2005)…. Today, New Yorkers and visitors alike take for granted that all of the city’s architectural, historical and cultural treasures will always be there.” With New York real estate values continuing to rise, Wood warns that “the political pressure to both weaken the protection of existing landmarks and halt the designation of new ones is at an all-time high.” “Vigilance,” warns Wood, “is the price of preservation and public complacency is the greatest threat to its future.”

Richard Moe, president emeritus of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, has summed up well why the Landmarks Law and the work of the Landmarks Preservation Commission remain critical to New York City: “There may have been a time when preservation was about saving old buildings, here and there, but those days are gone. (Today) preservation is in the business of saving communities and the values they embody.”

To celebrate its fiftieth anniversary in 2015, Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, preservation activist and former director of the New York Department of Cultural Affairs, has launched the New York City Landmarks50 Alliance. One major event celebrating the anniversary is Saving Place: Fifty Years of New York City Landmarks, opening April 21, 2015, at the Museum of the City of New York (www.mcny.org). Illustrating the role of preservation in New York City during the last fifty years, the exhibition will be on view through the summer. During 2015, Diamonstein-Spielvogel and an advisory board made up of many of the city’s most visible cultural and preservation ambassadors will work with over one hundred-and-fifty institutions throughout the five boroughs to showcase a year of lectures, exhibitions, tours, and classes intended to inform the public about preservation’s role in protecting the historic fabric of New York (www.nyclandmarks50.org).

- Fig. 8: Singer Building, Liberty Street and Broadway; built 1908–1909, Ernest Flagg, architect. Even since the passage of the Landmarks Law, New York has lost some incredible architectural treasures. The headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, the Singer Building was the tallest building in the world until it was demolished in 1967 and remains the tallest building ever to be demolished. The AIA Guide to New York City called this the “city’s greatest loss since Penn Station.”; Courtesy, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (LC-USZ62-67472).

Grace Friary (gracefriary@comcast.net) is a marketing and development consultant working with museums and cultural institutions throughout the United States. She is grateful to Anthony C. Wood and Matthew Coody of the New York Preservation Archive Project for assistance in the preparation of this article www.nypap.org.

This article was originally published in the Anniversary 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. A former board member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and a recipient of the Historic Districts Council’s Landmarks Lion Award, Anthony Wood is founder and Chair of the New York Preservation Archive Project, a non-profit organization dedicated to documenting, preserving and celebrating the history of historic preservation in New York City.