Reflecting Changes in Taste and Fashion: Tankards and Teapots from the Glen-Sanders Collection

From great-grandmother’s quilt to George Washington’s watch seal, we venerate things from bygone days as tangible links to our personal and national histories. Among the varied artifacts from earlier generations, silver is particularly potent in recording lives lived long ago. Silver items often were marked by the master of the shop in which they were made, and receipts of payment occasionally survive for these costly items.

Silver was commonly engraved with the initials or coats of arms of its owners, in part to boast of possessing luxury goods and in part to ensure a greater likelihood of recovery in the event of theft. Later generations often removed, added to, or altered monograms and inscriptions to maintain anonymity when items were sold, to commemorate significant events, to record lines of descent, or to lay claim to current ownership. And unlike many other materials, silver could be altered or modified with relative ease to reflect changes in usage or fashion. Collectors and curators prize pieces in untouched condition, but in truth, little has survived the centuries without being “mended” or having “bruises” taken out, or being “scoured” or “burnished.” The frequent appearance of these terms in colonial silversmiths’ accounts and advertisements serves as a reminder that silver, like furniture, was frequently sent to craftsmen for freshening up as decades of wear and tear accrued.

In 1964, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation acquired the contents of a house called Scotia, built around 1713 in what is now Schenectady County, New York. The assemblage mirrors the lives of multiple generations of descendants of the early Dutch settlers of the Hudson River Valley, including, among others, members of the Glen, Sanders, Van Rensselaer, Elmendorf, and Ten Broeck families. The collection comprises paintings, furniture, ceramics, textiles, and glass, as well as silver and gold. Not surprisingly, the marked precious metals all originated in the shops of either New York or Albany silversmiths.

Silver from Mine to Masterpiece, a long-term exhibition at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, features a portion of the silver and jewelry in what is today known as the Glen-Sanders collection.1 A library and manuscript collection was also part of the Scotia materials. In addition to scores of books and family Bibles, the documents include manuscript ledgers and accounts, shipping records, correspondence and receipts, inventories and wills. These materials are now held by the New-York Historical Society.2

Tankards were common communal drinking vessels in America throughout the colonial period. Silver examples were both a sound means of displaying wealth and taste, and a useful form of tableware. The Glen-Sanders collection at Colonial Williamsburg includes two examples that typify the regional preferences of New York residents. A 1700–1720 tankard marked by Cornelius Kierstede (Fig. 1, left) features the rich style of ornament associated with early silver made in New York. Its broad, squat stance, cut-card and wriggle-work base band, handle with lavish cast figural ornamentation, and engraved, crenelated lid embody the full spectrum of characteristics associated with Dutch-influenced New York silver. The tankard is engraved with the unidentified initials “CG” on its handle, and with an elaborate mirror cypher “VR” on its cover for the Van Rensselaer family. The initials “EPVR” are engraved in sprigged script on its body for a later owner, Elizabeth P. Van Rensselaer (1771–1798).

A second tankard, marked by Jacob Gerritse Lansing and dating to 1735–1745, reflects the increased simplicity that occurred in New York silver over time (Fig. 1, right). Gone are the rich base band and handle ornamentation, replaced by simplified moldings and a beaded drop. The cocoon-shaped thumbpiece, coupled with the enduring flat-topped lid, are the signature features of mid-century tankards from this region. Block tripartite initials on its base “D/IS,” engraved in the Dutch New York style, with the woman’s given name uppermost (Fig. 2), record the tankard as the property of Deborah Glen (1721–1786) and John Sanders (1714–1782), who married in 1739. Although fashionable and useful at the time of its making, by the early nineteenth century, changing social customs and the growing temperance movement made vessels for the communal consumption of alcoholic beverages undesirable. Many silver tankards were sold, melted, and reworked into more fashionable forms.

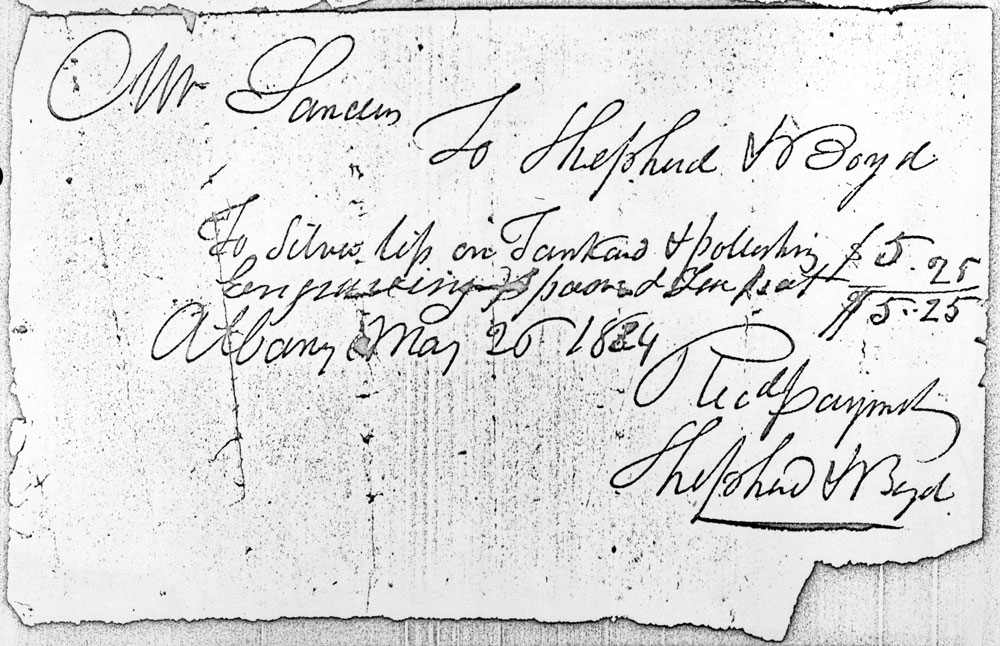

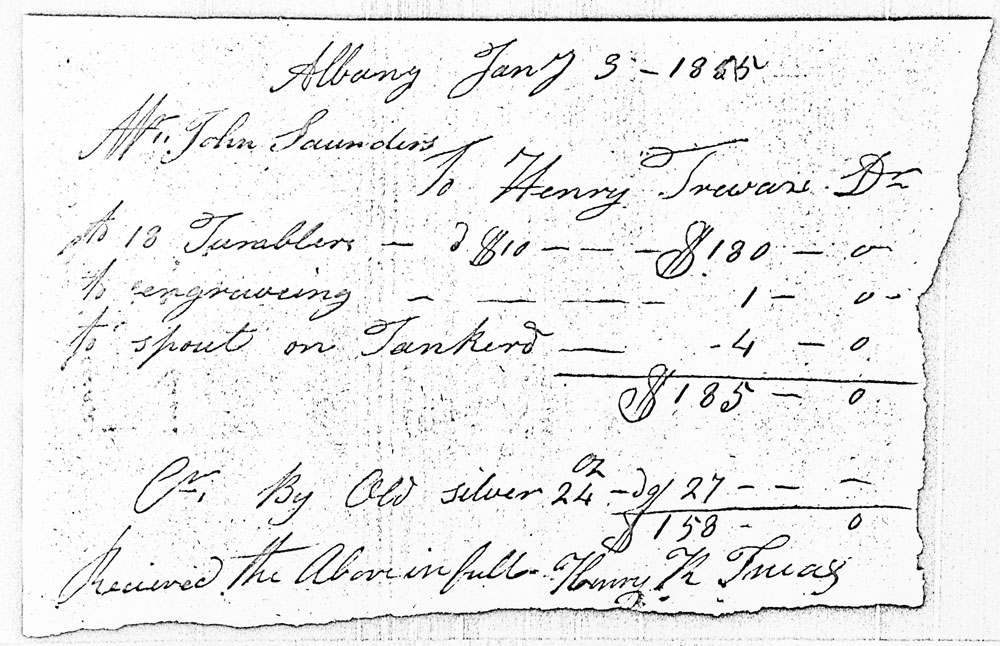

Among the Glen-Sanders papers, two receipts from the mid-1820s document Albany silversmiths Shepherd & Boyd and the lesser-known Henry R. Truax altering tankards for the Sanders family by adding spouts (Figs. 3, 4). Photographs from the 1960s document the appearance of the Lansing tankard with its spout still in place (Figs. 5, 6). While many tankards were converted for use as water pitchers through the addition of a lip opposite the handle, a Glen-Sanders descendant recalled these family relics being used as coffeepots in the twentieth century.3 In the mid-1960s, the pouring lips of these tankards were removed in an attempt to restore them to their original appearance. Close inspection of the surface area of the body reveals the telltale presence of the now-filled holes from the mid-1820s spouting (Fig. 7).4 Today, many curators and collectors would advocate keeping the spouts intact on both tankards as evidence of the objects’ changing function over time.

Although no purpose-made coffeepots survive among the Glen-Sanders silver, several teapots document the consumption of that beverage within the extended family. Two of the teapots were fashioned in the pear-shaped form widely embraced by both patrons and silversmiths of New York City and the Hudson River Valley. One of the pots is unmarked (Fig. 8, right), and the identity of the silversmith who struck an “IB” mark on either side of the handle on the other teapot remains a mystery (Fig. 8, left). This “IB” touchmark (Fig. 9) has not been found thus far on pieces associated with any identified silversmith. Among the many New York makers of pear-shaped teapots are Jesse Kip, Jacob Gerritse Lansing, Peter Van Dyck, Henricus Boelen II, Tobias Stoutenburgh, Myer Myers, and Daniel Christian Fueter. Dates ascribed to published examples by these smiths range from around 1715 to as late as 1769.

The “IB” marked teapot is engraved on its base with two sets of initials (Fig. 10). The triangular arrangement inscribed around the base’s center point, “R/IE,” has not been identified thus far. The lower monogram “PEE” was clearly engraved by a different hand, as shown by the heavier shading of the letters and the execution of their serifs. The engraving might reference Peter Edmund Elmendorf (1715–1765), who in 1744 married Mary Crook(e) (1721–1794). This attribution is further strengthened by the initials on the base of the unmarked teapot (Fig. 11). Once again, two monograms were engraved. The lower inscription “C-G-B” is unidentified. However, the upper set of letters, “ME,” both correspond to the married name of Mary Crook(e) Elmendorf and features the same style of weighty shading and enlarged serifs seen in the “PEE” monogram on the marked teapot.

The Glen-Sanders pear-shaped teapots are difficult to date. The lack of clear provenance and persistence of the form over a span of approximately fifty years compound the problem. Almost identical in appearance, the teapots vary most noticeably in their hinges, handles, and handle sockets. These features, however, are the most frequently repaired and replaced elements on any tea- or coffeepot. The stubs of wooden handles pinned within silver sockets easily become damaged from water and polishing agents, and are prone to splitting or cracking. When a handle gives way, the ferrule or socket frequently rips, too, necessitating the drilling of a new hole for the pin. With prolonged and vigorous use over time, the process of repairing and replacing a handle might be repeated. Indeed, at the same time in the 1960s when the spouts were removed from the Kierstede and Lansing tankards, the handle on the “IB” teapot was replaced and the hinge on the lid was repaired.5 The idiosyncratic lower handle juncture, however, was almost certainly the result of an earlier campaign to maintain the teapot’s usefulness.

These examples are among the approximately 170 objects dating from circa 1530 to 1835 on exhibit in Silver from Mine to Masterpiece. Organized by Janine E. Skerry and on view at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum at Colonial Williamsburg through January 7, 2018, the exhibit marks the reinstallation of Colonial Williamsburg’s silver galleries. Celebrating its 30th anniversary in 2015, the museum houses a world renowned assemblage of early British silver and Sheffield plate and has been actively acquiring early American silver since 2009. The exhibition has received generous support from the Mary Jewett Gaiser Silver Gallery Fund.

-----

Janine E. Skerry is curator of metals at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. For a brief description of the library and manuscript materials, see The Glen-Sanders Collection from Scotia, New York, p. 47. The library and manuscript collection was microfilmed in the early 1970s prior to its transfer to the New-York Historical Society; eighteen rolls of microfilm of this material are now held at the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg.

3. Reminiscence in 1966 of Mrs. J. Glen Sanders (1893–1982), as recorded in Glen-Sanders accessions files at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

4. The restoration work was done in 1964 by Robert Ensko, Inc., of New York City, as documented by correspondence in the Colonial Williamsburg accession files, 1964-270 and 1964-271.

5. Colonial Williamsburg accessions file, 1964-274.