Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art

|

by Dr. Alan Granby

And having fitted well our ship To pass Cape Horn again, Each man then, fore and aft the ship, Scrimshauning did begin.

Then knitting sheaths and jagging knives Were cut in every form, And other trinkets for the girls, As presents from Cape Horn.2 — From a whaler’s journal, 1820–1823 voyage |

Scrimshaw is the art of engraving on or carving items from whale bone, sperm whale teeth, walrus tusks, baleen, and other material byproducts of the nineteenth-century whaling trade. When the whalemen were not engaged in active hunting, processing whale blubber into oil, or routine maintenance of the vessel, they artfully engraved as well as carved all types of utilitarian and decorative items. More so than other mariners, whalers created their own forms of literature, song, and art, and by the mid-nineteenth century, they had developed stylistic conventions and technical skills that distinguished scrimshaw as a distinct occupational handcraft genre.1

Resourceful whalers used simple tools like needles or jack knives to engrave the teeth or bone, to which they applied materials, such as lampblack, ink, and sealing wax, that left the engraved lines darkened when rubbed off. The range of scrimshaw objects varied from simple, basic engravings to elaborate decorative constructions that required years to make. These intricate and remarkable pieces were often made as gifts for loved ones back home and served as personal mementos of particular voyages. In addition to their beauty, scrimshaw objects provide valuable documentation and insight into the whaler’s life.

Scrimshaw: the Whaler’s Art, at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Massachusetts, tells the surprising history of this unique art form through the stories of makers and recipients of these intricately detailed keepsakes. The exhibition contains more than two hundred important examples of a wide range of decorative and utilitarian objects that evoke connections to historic life on Cape Cod, Nantucket, and New Bedford. Works included are by known scrimshanders Caleb Alboro, Edward Burdett, Nathaniel Finney, William Gilpin, Frederick Myrick, William Lewis Roderick, Banknote Engraver, Naval Engagement Engraver, and several anonymous scrimshanders. On public display for the first time is a scrimshaw whale’s tooth attributed to Nantucket whaleman Edward Burdett (1805–1833) on board the ship Japan of Nantucket during a voyage between 1825 to 1829. Paintings by William Bradford (1823–1892), William John Huggins (1781–1845), and Frederick Jewett (1819–1864) complement the scrimshaw with visual and contextual information on the maritime trade.

|

|

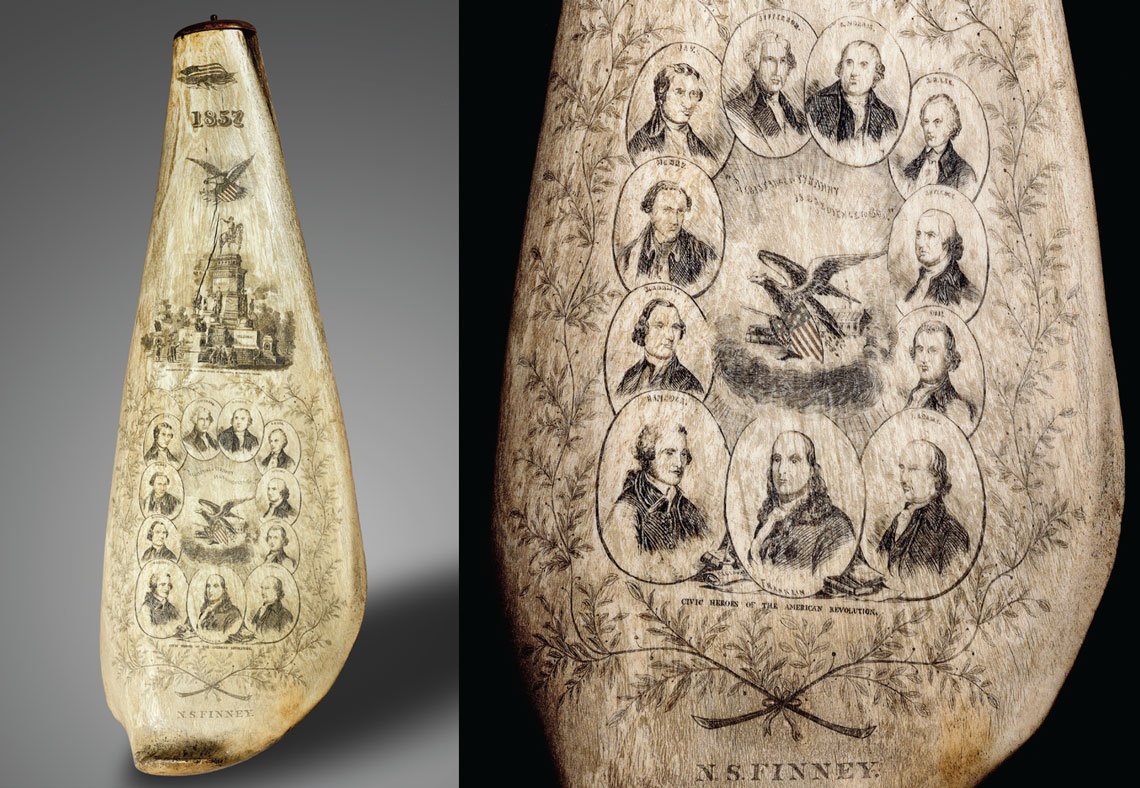

Nathaniel Sylvester Finney (1813–1879), Civic Heroes of the American Revolution, 1857. Whale panbone, metal, wood, pigment, L. 42¼, W. 15, D. 7½ in. Collection of and image courtesy of Mariners’ Museum and Park (1933.0134.000001). |

Nathaniel Sylvester Finney may be the only former whaleman to become a professional scrimshander after retiring from whaling. Regarded as among the most technically accomplished of the pictorial artists, his rendition of key historic figures of the American Revolution displays the breadth of his skill. Born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, records of his voyages include a tour as second mate of the Bramin, as second mate of the Rodman, and as first mate of the Bartholomew Gosnold, all originating out of the port of New Bedford. Beginning in the late 1860s, he lived in San Francisco, out of a shop on Meiggs Wharf, a lively locale clustered with nautical and curiosity shops, described as a “lounging place for ancient mariners.” This large engraved panbone—a section from a sperm whale’s jaw—appeared in the New Bedford Republican Standard and the San Francisco Bulletin in 1857. Taken from a “20-barrel sperm fellow” that Finney participated in killing, it was engraved by him with heroes of the American Revolution and portraits of politicians. The images were based on illustrations in books and magazines, adjusted to fit the size and shape of the panbone.

|

|

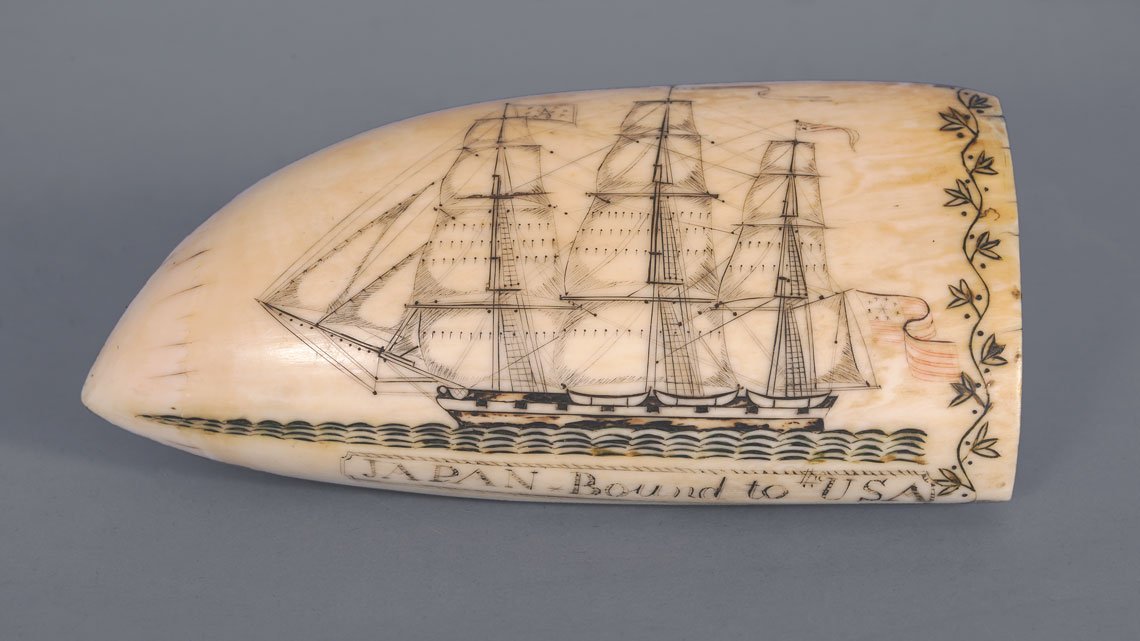

Attributed to Edward Burdett (1805-1833), Whaleship Japan of Nantucket Homeward Bound to the USA, ca. 1825–1829. Sperm whale tooth, pigment. L. 5¾ in. Private collection. Image courtesy of Eldred’s Auction Gallery. |

Born on Nantucket, Edward Burdett was the son of a prominent merchant sea captain. He went on his first voyage at the age of seventeen, on the ship Foster, under Captain Shubael Chase. His last voyage was aboard the Nantucket whale ship Montano in 1833, when, while in pursuit of a harpooned whale, Burdett became entangled in the line, was yanked overboard and drowned. Deaths were commonplace aboard American whale ships in the nineteenth century, yet few were caused by whales or occurred during pursuit. This tragic accident was a dramatic exception. Burdett was also a master scrimshaw artisan. In this example, demonstrating skilled attention to the ship’s details, rather than incising the lines of his design, Burdett gouged out the surface of the ivory in certain areas, resulting in a more powerful image. A remarkable depiction of a moment of life at sea and the business of whaling, it has never before been publicly exhibited. Engraved “JAPAN – Bound to the USA,” it is thought to be the first example of a scrimshaw tooth by Burdett, and since he was one of the earliest American scrimshanders, this engraved whale tooth is possibly the first known example of American scrimshaw. The history of the tooth has been recently documented in an essay by noted scrimshaw expert and historian Paul Vardeman.

|

|

Attributed to Britannia Engraver, The Ship Charles of London, second quarter 19th century. Sperm whale tooth, pigment. L. 5¼ in. Private collection. Image courtesy of Eldred’s Auction Gallery. |

Imaginative in design and bold in execution, this tooth, inscribed with the name of the ship Charles of London, is attributed to the British scrimshander known as Britannia Engraver, thought to be among the first whalemen scrimshaw artists. The practice of engraving pictures on sperm whale teeth likely originated with British mariners in the London South Sea sperm whale fishery shortly after the Napoleonic Wars. One side of the tooth depicts an active whaling scene with a sperm whale stoving a whale boat, sending harpoons, lances, a water cask, and four whalemen flying into midair. The Britannia Engraver relief-carved the tail of the whale in black above the waterline and left the whale uncolored in outline underneath the water. The scene shows eight additional whales and the stern of a whaleboat heading fast toward a whale. A relief-carved scallop and pique border encircles the base.

|

|

Frederick Stiles Jewett (1819–1864), Ship Huntress Off Cape of Good Hope, ca. 1850. Oil on canvas, 59 x 35 inches. Collection of and image from a private collection. |

After an early career on whaling ships, Connecticut artist Frederick Stiles Jewett devoted the last seven years of his life to painting the sea. In this dramatic whaling scene, a large sperm whale is portrayed fighting for its life, while a much-smaller whaleboat moves in for the kill. The mate stands at the bow, poised to drive his lance into the whale’s lungs. The deep red tones of the whale’s spouting blood are echoed in the fiery colors of the sunset that reflect on the bloodied waves, signifying the end of the day’s work and the metaphorical ending of the whale. The influence of British painter J.M.W. Turner, whose work Jewett studied during trips to Europe, can be seen in the gestural application of paint in the sea and sky. The New Bedford whale ship Huntress, which made several voyages through the waters off South Africa, approaches at right. Further in the right background, another whale and whale ship are silhouetted.

|

|

James Adolphus Bute (ca. 1799–mid-19th century), Darwin Expedition, ca. 1831–1836. Whale tooth, pigment. L. 7 in. Private collection. Image courtesy of Eldred’s Auction House. |

This scrimshaw tooth was engraved by Englishman James Adolphus Bute aboard the H.M.S. Beagle during Charles Darwin’s expedition. Born around 1799, Bute had joined the Royal Navy in around 1819. There was often crossover between whaling and the naval service in England, and Bute may have been introduced to scrimshaw during a whaling voyage between stints on naval vessels. In his journal, Syms Covington, assistant to Darwin, lists Bute as a crew member on his second voyage aboard the Beagle (1831–1836), one of six crew members listed as royal marines. The Beagle sailed from Plymouth Sound in 1831 under the command of Captain Robert FitzRoy. While the expedition was originally scheduled to last two years, the Beagle did not return until 1836. Published accounts of the voyage note that in early April 1834, the Beagle was laid on shore for repair in an estuary of the Rio Santa Cruz in Argentina. While repairs were being made, Darwin explored further upriver, with the men having to haul the boats they took with them for most of the journey. Both of these events are illustrated on the tooth. Conrad Martens, the official artist aboard the Beagle, also captured these events in two drawings that mirror the images on the tooth. Given the similarities between Bute’s and Martens’s work, it is possible that Bute was influenced by or collaborated with the artist in creating his pieces of scrimshaw.3

|

|

Pie crimper, 19th century. Whale bone, baleen, copper pin. L. 8½, W. 4¾, D. ¾ in. Collection of and image courtesy of Heritage Museums and Gardens (1972.6.8). |

Pie crimpers, also called jagging wheels, were used to seal the edges of a pie or pastry (most pies in the nineteenth century were savory and contained meat and sauces). Where simple pie crimpers had straight handles and plain, thin-bladed wheels, with a jagged edge for cutting fluted edges into pie crust, ornate versions had elaborately shaped handles and other distinctive features. This intricate example features a looped serpent handle, a pierced work wheel with star and hearts design, and a complex carved pastry stamp and fork.

|

|

Polychrome Whale’s Tooth Depicting Alwilda, the Female Pirate, mid-19th century. Whale tooth, pigment. L. 6 ½ in. Private collection. Image courtesy Eldred’s Auction Gallery. |

This tooth portrays the female pirate Alwilda wearing a striking checkered skirt, while holding a sword above her head, with a dagger and pistol tucked into her sash. According to legend, Alwilda was the daughter of a Scandinavian king. Her overprotective father locked his beautiful young daughter in a tower surrounded by snakes, to keep men away from her. The Prince of Denmark succeeded in defeating the snakes, and the king agreed to arrange a marriage. However, Alwilda had no intention of complying. Helped by her mother, Alwilda fled, and joined a group of female sailor friends who dressed like men. Together they commandeered a ship, and elected Alwilda their captain. Pursuing Alwilda, the prince boarded her vessel, and having killed most of her crew, killed the captain too, not recognizing Alwilda dressed as a man.

|

|

Captain Henry Daggett, Yarn swift with storage box, 1834. Whalebone, silver, wood, 23½ inches high. Private collection. |

Yarn swifts are often regarded as the pinnacle of the scrimshaw makers’ art, since they required intricate engineering and painstaking cutting, polishing, and assembly of dozens of interrelated parts. Swifts were used to convert skeins of yarn into balls, so that the yarn would not get tangled while knitting. Whalemen who built swifts at sea are known to have spent two to three years creating them, making them the most precious of scrimshaw gifts, usually designed for a sweetheart or wife.

The swift shown here is a superb example of design, beauty, and execution. It was created by Captain Henry Daggett (1811-1873). Though he sailed on many whaling voyages, his legacy lies in the scrimshaw swifts he made during his seafaring years. Daggett made this swift for Caroline Mayhew (1800-1880) on the event of her marriage to Capt. William Mayhew, Jr. (1798-1855), Daggett’s fellow whaling master and Martha’s Vineyard neighbor. The couple is represented on the front of the wooden storage box, which bears a whale ivory heart engraved with a man and woman in formal dress, representing the bride and groom.4

|

|

Scrimshaw tub, 19th century. Whale bone, baleen. Collection of and image from a private collection. |

Constructed from a scrimshaw base plate and multiple staves, this tub features elaborately carved heart-shaped handles, a scalloped edge decoration, and is bound with baleen hoops. Made at sea, it would have been used for washing clothes and household linen back home on land.

|

|

Attributed to Manuel Silvia (n.d.), Whale Ivory Trinket Box in Shape of Ship Hull, ca. 1860–1870s. H. 1½, W. 6¼, D. 1½ in. Collection of and image from the Nantucket Historical Association (1991.0496.001). |

The attributed maker of this whale ivory trinket box is Manuel Sylvia, an Azorean whaleman who sometimes worked aboard New Bedford vessels. He created this exquisite treasure box out of a whale tooth. The hull has six scrimshawed guns on each side, and an elaborate colored scrimshaw design of roses and leaves covers the lid; the quarterboard is inscribed “FLORINDA.” Florinda (1840–1906) was the scrimshander’s wife. Born on the island of St. George in the Azores, she married Sylvia in New Bedford in 1864. In 1873, she petitioned the probate authorities in Fall River to sell a tract of land in New Bedford that was owned by her husband, as he was away at sea on a whaling voyage and she had not heard from him “directly or indirectly” for four years. She was granted permission to sell the land, which she did for $400.

|

|

Carved Scrimshaw Cane with Inlay, mid-19th century. Whale ivory, whale bone. L. 35 in. Private collection. Image courtesy Eldred’s Auction Gallery. |

Canes of many types were produced aboard whale ships. This carved, scrimshawed, and inlaid whale ivory and whalebone cane exhibits workmanship of the highest caliber. The scrimshander carved the handle out of whale ivory as a fist clenching a snake (the human fist was a commonly used motif); the snake is coiled around the hand and wrist above a shirtsleeve, detailed with engraved trim and applied buttons. The snake has inlaid eyes, a forked tongue, and deeply engraved scales. The tapered whalebone shaft of the cane has been inlaid with shell in a delicate saw tooth and tassel design and silver metal inlays of a harpoon and lance. In the nineteenth century, canes were as much a fashion accessory as a utilitarian item.

|

|

Polychrome scrimshaw whale’s tooth, mid-19th century. Whale tooth, pigment. H. 6 in. Private collection. Image courtesy of Eldred’s Auction Gallery. |

Patriotic themes carry through the history of American scrimshaw, with images of eagles, American flags, and personifications of ideals such as Hope, Liberty, and Justice. This colorful engraved tooth features a spread-wing eagle clutching a red, white, and blue shield in its talons, and a red, white, and blue banner in its beak. An American twelve-star flag wraps nearly halfway around the tooth. The eagle’s wings, which have finely detailed feathers, reach almost entirely around the circumference.

|

1. Stuart M. Frank, Ingenious Contrivances, Curiously Carved: Scrimshaw in the New Bedford Whaling Museum (New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2012), 15–17.

2. Passage from the private journal of whaleman Charles Murphey, “A Journal of a Whaling Voyage on Board Ship Dauphin of Nantucket,” from an 1820–1823 voyage, published in 1877.

3. Frank, Dictionary of Scrimshaw Artists (Mystic, Conn.: Mystic Seaport Museum, 1991), 24.

4. As a girl in school, Caroline learned navigation along with painting, embroidery, and “use of the globe.” It was not unusual for women to accompany their husband’s on whaling voyages, as did Caroline. Caroline and William made three whaling voyages together. On the final voyage, William and eight crewmen came down with smallpox, and Caroline, the daughter of a doctor, not only nursed them back to health, but also assisted with navigation while William was incapacitated.

|

Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art is organized by and on view at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., from June 29 through October 30, 2022. A companion catalog, Wandering Whalemen and Their Art: A Collection of Scrimshaw Masterpieces accompanies the exhibition. Authored by Dr. Alan Granby, with a forward by Dr. Stuart M. Frank, the world-renowned scrimshaw expert. This 376-page book is available at cahoonmuseum.org/visit/museum-shop/. For details on the exhibition and associated programs, visit cahoonmuseum.org/event-calendar/.

Dr. Alan Granby is one of the world’s leading experts in the identification, evaluation, and appraisal of scrimshaw. He is co-founder of Hyland Granby Antiques and guest curator of Scrimshaw: The Whaler’s Art.