The Marquis de Lafayette and George Washington

The major commemoration in the United States of the 250th anniversary of the birth of the Marquis de Lafayette will inaugurate Mount Vernon’s new changing exhibitions gallery. A Son and his Adoptive Father: The Marquis de Lafayette and George Washington, organized in partnership with Lafayette College, is comprised of more than 125 artifacts drawn from some twenty museums and private collections. Portraits of Washington and Lafayette, ceramics, silver, glass, weapons, jewelry, textiles, memorabilia, letters and other documents have been organized into three chronological sections that trace Lafayette’s impact on America and his relationship with the Washington family.

A Missionary of Liberty, 1777–1779

Lafayette’s introduction to the American cause came at a dinner in 1775, given by his superior officer, the Comte de Broglie. There he met the Duke of Gloucester, brother of King George III, who spoke sympathetically about the struggle going on in the American colonies. So passionate was Lafayette to join the fight for independence in the American colonies that—against the wishes of family and king, and without the knowledge of his wife—he set sail on April 20, 1777, for a place he had never seen. The inexperienced nineteen-year-old learned English on his journey across the Atlantic. In Philadelphia on July 31, 1777, Lafayette met George Washington, then forty-five years old, and the two men formed a life-long friendship, united by a common belief in individual liberty and a democratic society. Lafayette found in Washington a father figure. To Washington, who had no children of his own, the courageous Lafayette met his expectations of the ideal son. Like Washington, Lafayette served without pay, supporting himself and his troops. Later, he played a critical role in bringing France into the war, which contributed to the decisive victory at Yorktown.

In the years following the Revolutionary War, the Washington and Lafayette families exchanged gifts and corresponded frequently, and Lafayette returned to America in 1784 to visit his “family” at Mount Vernon. After the French Revolution broke out in 1789, the connection between the Washington and Lafayette families became even stronger when Lafayette’s wife entrusted the Washingtons with the safety of their fifteen-year-old son, George Washington Lafayette. When Washington died in 1799, less than three years after his second term in office, Lafayette wrote to Alexander Hamilton of the “Lamentable Loss to Mankind” and “to Me His Adoptive and Loving Son.”

The Nation’s Guest, 1824–1825

At the invitation of President James Monroe on behalf of the American people, Lafayette returned to the United States as “the nation’s guest” on August 15, 1824. His landing in New York saw the first of many exuberant celebrations. During a thirteen-month period, Lafayette—accompanied by his son—visited all twenty-four states, where he was fêted with parades, public orations, private dinners, gala balls, and honors. In Lafayette, Americans saw a living link to George Washington and the glories of the founding era.

History painter John Vanderlyn depicted Washington and Lafayette on horseback, riding heroically across the Brandywine battlefield near Philadelphia. Although rendered nearly fifty years after the 1777 battle, the painting captures the confidence and gallantry of these two Revolutionary War leaders. Lafayette was wounded at Brandywine, the first battle in which he fought for the American cause. While recuperating, he wrote to his wife, “Do not be concerned, dear heart, about the care of my wound…. When he [Washington] sent his chief surgeon to care for me, he told him to care for me as though I were his son, for he loved me in the same way.” Washington and Lafayette fought side by side in several other battles.

- Salver, France, circa 1783. Silver plate. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John H. Gibbons, 1985. Wine Coaster, France, circa 1783. Silver plate, wood. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Purchase, 1981. Conservation courtesy of the Life Guard Society of Mount Vernon. Photography by Gavin Ashworth.

Interested in owning fashionable goods, Washington wrote to Lafayette on October 1783 requesting that he send him an array of silver-plated tea wares and other tablewares including “Two smaller size [salvers] for 6 wine glasses each” and “eight bottle sliders.” By March 1784 Washington had received the items from France, including this salver (tray) and bottle slider (wine coaster). The tray is decorated with a simple beaded edge and engraved coat of arms; Washington had stated that “If this kind of plated Ware will bear engraving, I should be glad to have my arms thereon.” The wine coaster exhibits more intricate neoclassical design elements, with pierced and engraved swags and floral motifs. The Washingtons used these elegant pieces to entertain the many guests who made their way to Mount Vernon to pay their respects to the victorious American general.

In November 1786, Washington received from Lafayette two partridges, three asses, and seven pheasants. The asses had been requested for use on the farm at Mount Vernon, but Washington was surprised by the gift of birds from the aviary of King Louis XVI. Charles Willson Peale, artist and friend of Washington, heard of this unusual cargo and requested that Washington send him the pheasants, upon their death, for his Philadelphia museum. In January 1787 Washington responded to Peale. “I cannot say that I shall be happy to have it in my power to comply with your request by sending you the bodies of my pheasants; but I am afraid it will not be long before they will compose a part of your museum, as they all appear to be drooping.” Washington kept his word to send the pheasants as they “make their exit.” Preserving these two golden pheasants was among the earliest of Peale’s forays into taxidermy, a process he would perfect over the coming years. Peale’s museum in Philadelphia, which showed preserved examples from the natural world alongside portraits and sculptures of the world’s great men, was a pioneering venture that Washington supported through an annual subscription.

By 1824, as the people of Philadelphia planned for the arrival of Lafayette, Thomas Sully had established himself as one of the city’s foremost portrait painters. Prior to Lafayette’s 1824 trip to America, a committee calling themselves The Citizens of Philadelphia sent a letter to Lafayette stating that “A number of our most respectable citizens are desirous of presenting to the city of Philadelphia your portrait by Sully, should you consent to sit for it.” Lafayette sat for an ink and watercolor sketch in December 1824. It is unclear whether Lafayette sat for Sully again during his 1824–1825 tour. According to Sully’s register, this small study for the large Philadelphia commission was begun on January 16, 1826, but then “put by” and not completed until 1833. Sully had gained a reputation for painting flattering portraits, and this image of Lafayette is no exception. The aging Frenchman’s wrinkles have been smoothed out, his toupee looks natural, and his stance portrays a vigorous hero. The parade welcoming Lafayette to Philadelphia is depicted in the background.

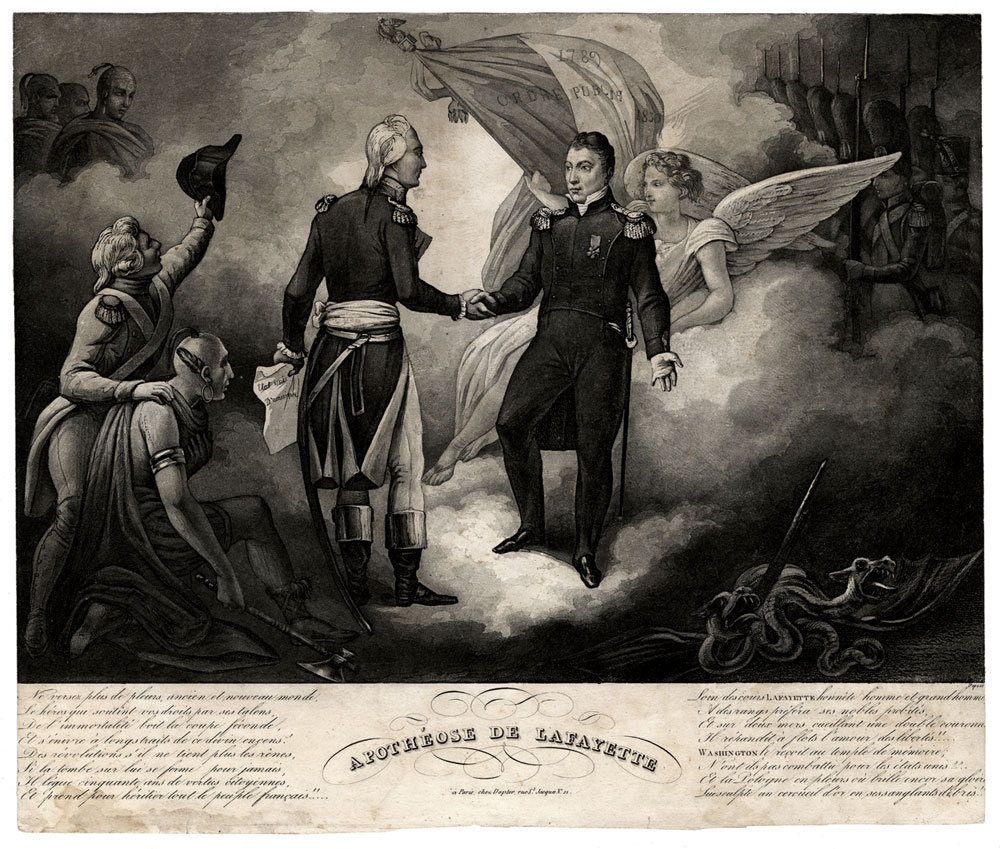

When news of Lafayette’s death reached America, it spurred a national outpouring of emotion. His death gained significance since it marked the passing of one of the nation’s last living links to the Founding Fathers. In this print by an unidentified artist, General Washington welcomes his close friend and ally to heaven, or as the print’s text suggests, the temple of eternal fame. The marquis is escorted by an angel and by French soldiers. An American Indian, representing the United States, kneels before both heroes, while a French soldier from the American Revolution greets Lafayette by removing his hat. Following their deaths, the likenesses of Washington and Lafayette appeared in a number of similar prints that communicated their godlike status and the enduring importance of their character and accomplishments.

Commemorative ceramics, often common tablewares such as platters, plates, teapots, and pitchers, were abundant during Lafayette’s tour. From 1819 to 1834, the Staffordshire ceramic manufactory of J & R Clews made transfer-printed wares in a variety of colors, with blue being the most predominant. Many of the designs by the brothers were based on popular prints of the time. That is the case with this platter, part of a dinner service, depicting the scene of Lafayette’s 1824 arrival at Castle Garden in New York, where 30,000 Americans gathered to welcome him. The image derives from the most commonly recreated image of Lafayette’s tour by American engraver Samuel Maverick. Lafayette’s ship Cadmus is escorted by eight additional ships, the American flag with its twenty-four stars flapping in the wind, and the smoke of a cannon salute from Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor billowing in the air. The August 17 issue of the Commercial Advertiser reported: “The view of this fleet will perhaps never be forgotten. It was not only unique, but beyond a doubt one of the most splendid spectacles ever witnessed on this part of the globe.”

This is one of many silk-screened scarves that commemorated the arrival of American troops in France in 1917 and the subsequent Allied victory in World War I. Made in France, the scarves were often sold to American soldiers stationed there. This brightly colored pattern depicts the flags of each of the Allied countries, as well as likenesses of President Wilson, George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, and the Statue of Liberty, a gift from France to the United States in 1886. The images reflect the strong Franco-American alliance that dated back to the American Revolution, in which Americans and French—symbolized by Washington and Lafayette—fought side by side for the cause of liberty. At the conclusion of World War I in 1918, Wilson became the first U.S. president to travel abroad while in office when he sailed to France aboard the S.S. George Washington to attend the Versailles Peace Conference.

- Thomas Oldham Barlow (English, 1824–1889), The Home of Washington, after Thomas Pritchard Rossiter (1818–1871) and Louis Rémy Mignot (1831–1870), both American, 1860. Engraving. Publisher unknown. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. The Willard-Budd Collection; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Robert B. Gibby, 1984.

Thomas Rossiter and Louis Mignot were among many mid-nineteenth-century artists who depicted scenes from Washington’s life. The publication of several biographies of Washington in the same period, together with the preservation efforts of Ann Pamela Cunningham and the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, focused renewed attention on Washington as a private citizen. Rossiter and Mignot portrayed Washington, his family, and Lafayette on the piazza at Mount Vernon. In an essay accompanying the exhibition of their monumental painting, upon which this print is based, Rossiter wrote, “What thoughts of a hero’s repose are awakened at mention of the beloved home of the venerated and idolized Father of the Nation! What a Mecca of the Western hemisphere is its site!” Washington invited Lafayette to visit Mount Vernon in 1784, where Lafayette wrote to his wife: “I am reveling in the happiness of finding my dear general again; . . . our meeting was very tender and our satisfaction completely mutual.” In addition to furthering the new nineteenth-century interest in Washington’s domestic life at Mount Vernon, the print helped perpetuate the multilayered importance of the long relationship he had with Lafayette.

With a letter dated March 17, 1790, Lafayette, a leader in the French Revolution, sent his “Beloved General” two gifts. One was the main key to the Bastille prison, the storming of which on July 14, 1789, marked the beginning of the revolt. The second gift was a drawing of that “fortress of despotism…just as it looked a few days after I Had ordered its demolition.” Lafayette added, “it is a tribute Which I owe as A Son to My Adoptive father, as an aid de Camp to My General, As a Missionary of liberty to its patriarch.” Washington acknowledged Lafayette’s gifts, calling them a “token of victory gained by Liberty over Despotism….” After he retired from public life, Washington displayed the key and drawing in the central passage at Mount Vernon, where all entering guests might see them.

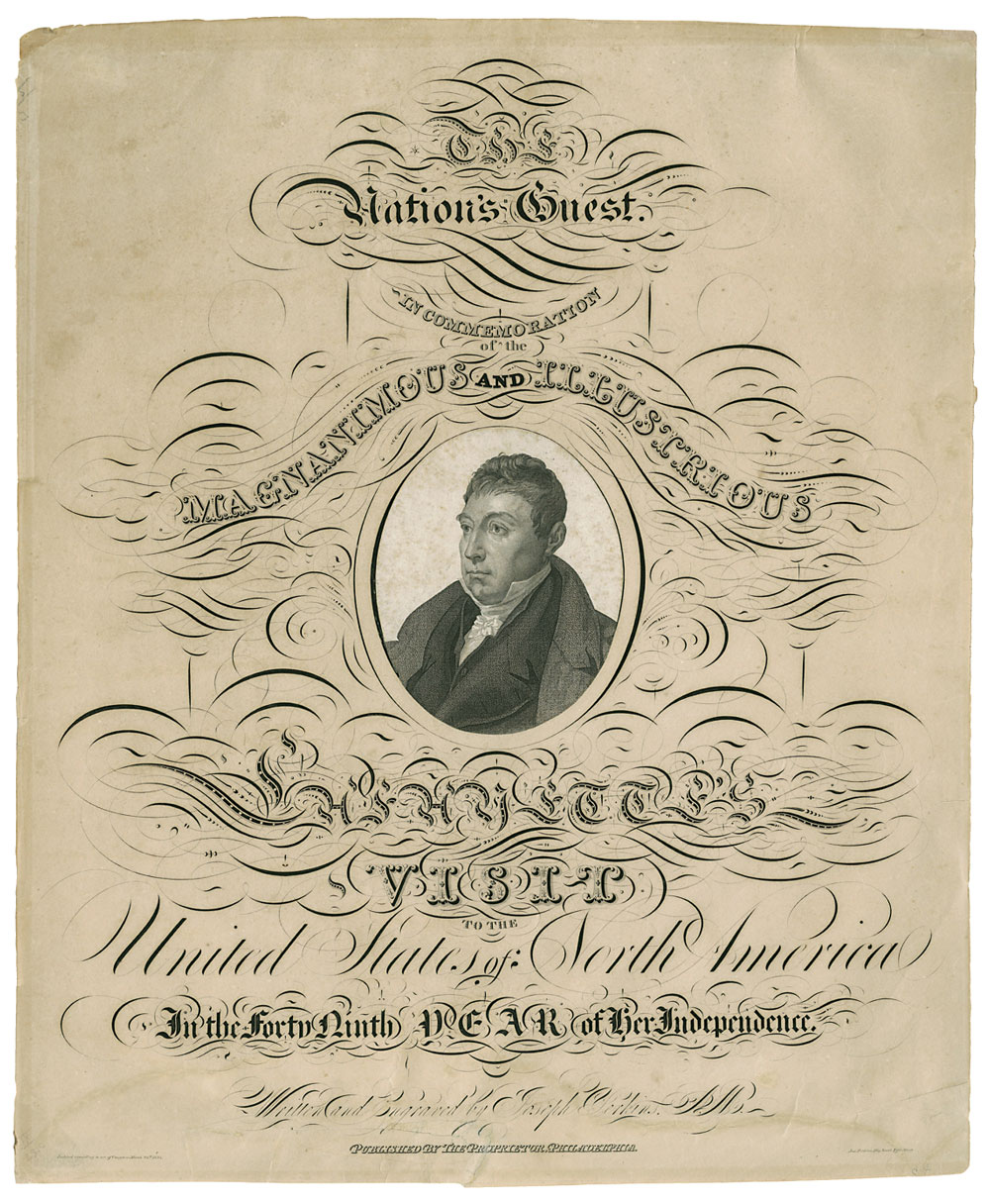

Lafayette’s triumphant 1824–1825 American tour spurred the creation of mementos and souvenirs. This elaborate calligraphic tribute reflects the exuberant welcome the marquis received throughout the country. The portrait of Lafayette is taken from Jean-Marie Leroux’s engraving of an 1823 portrait by Ary Scheffer. The Leroux print was the preeminent image of Lafayette during this era. Many artists and entrepreneurs used it when producing wares to commemorate and capitalize upon his popularity.

Their Fame Will Live Forever: The Enduring Legacy of Washington and Lafayette

Just as France and America had mourned the death of Washington in 1799, the two countries were brought together again in grief when Lafayette died on May 20, 1834. Americans mourned Lafayette’s death not only because of the gratitude and admiration they felt for him, but because his death marked the passing of one of the last Revolutionary War heroes.

Opening at Mount Vernon on October 27, 2006, A Son and his Adoptive Father: The Marquis de Lafayette and George Washington continues through August 5, 2007, then travels to Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania (August 27 through October 28, 2007), and to the New-York Historical Society (November 13, 2007 through March 9, 2008). The show will be accompanied by an illustrated publication and a variety of educational programs at each venue.

-----

Christine H. Messing, Assistant Curator, earned her degrees at James Madison University and George Washington University. She has been at Mount Vernon since July 2004.

John B. Rudder holds degrees from Washington and Lee University, the University of Virginia, and the Cooperstown Program in History Museum Studies. He became Special Projects Manager, Collections, in November 2004.