The Royall House and Slave Quarters: Interpreting a New England Plantation

In 1737, Isaac Royall Sr., “late of Antigua,” arrived in Massachusetts to take up residence in a newly built mansion outside of Boston—bringing with him “among other things and chattels[,] a parcel of negroes.” During the next four decades, more than sixty men, women, and children would be held in bondage on the Royall estate (Fig. 1).

Ever since Massachusetts outlawed slavery in 1783, starting a trend that led to the gradual end of this “peculiar institution” in the North, this important part of our national history has largely been forgotten. Instead, a more appealing narrative was constructed, one in which the North stood for liberty and the South for slavery, until the Civil War abolished slavery throughout the nation. The Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts, aims to set the record straight.

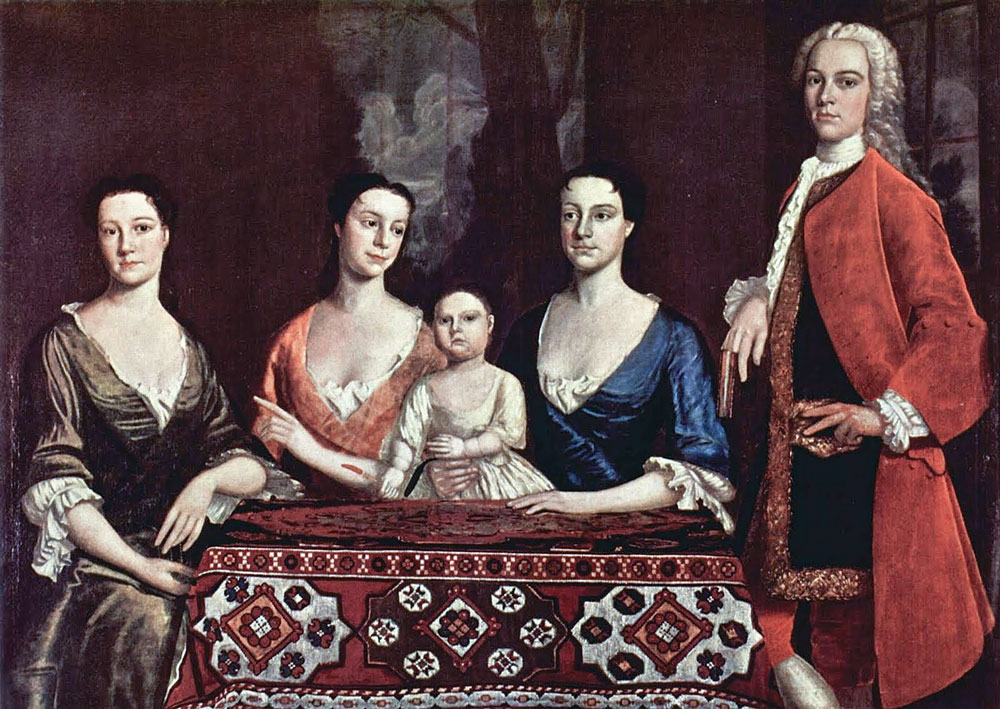

- Fig. 2: Robert Feke (1707-1750), Isaac Royall and His Family, 1741. Oil on canvas, 56-3⁄16 x 77-3/4 inches. Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library. Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Painted when Isaac Royall (1719–1781) was just twenty-two years old, and among the wealthiest men in the Massachusetts colony. This portrait shows, from right to left, Isaac Royall Jr., his wife Elizabeth, her sister Mary, and Isaac’s sister Penelope. The child is Isaac and Elizabeth’s first daughter Elizabeth, who died in 1747; her sister, born later that year, was also named Elizabeth.

The luxurious mansion and the stark slave housing—the only known freestanding slave quarters in the northern United States—along with many artifacts uncovered during extensive archaeological digs, vividly demonstrate the dependence of the Royalls’ lavish lifestyle on black labor (see figure 7). Tours stress the intertwined stories of wealth and bondage, set against the background of America’s quest for independence.

Isaac Royall Sr. made his fortune in Antigua as a slave trader and plantation owner, but when slave rebellions spread in the West Indies, he prepared to return to his native New England. In 1732, he purchased a five hundred acre farm in what is now the city of Medford, a few miles from Boston, and set about transforming it into a gentleman’s country estate. He expanded a colonial farmhouse into a three-story Georgian mansion considered one of the grandest houses of its era in North America, and—borrowing from practices common in the Caribbean—also constructed a summer “out kitchen” to keep heat away from the house in warmer temperatures. After five years of expansion and new construction, Royall and his family left Antigua for their new home, bringing twenty-seven enslaved Africans with them. Royall retained ownership of his valuable Antigua sugar plantation, which continued to depend on an enslaved workforce.

The Royalls were the largest slaveholding family in Massachusetts, and continued to purchase and sell individuals. When Isaac Royall Sr. died in 1739, his son and namesake inherited the family home and fortune—including the enslaved Africans. While those in bondage in Massachusetts produced wool, cider, and hay, and cared for the house and its white inhabitants, Isaac Royall Jr. enjoyed the fruits of their compelled labor. He used his wealth and leisure to become a leading citizen, serving as a member of the Governor’s Council, moderator of Medford’s Town Meeting, and an Overseer of Harvard College. Royall Jr. and his wife, Elizabeth, were well known for their elegant hospitality. Both John Singleton Copley and Robert Feke painted the richly attired Royalls, in portraits owned by, respectively, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Harvard University (Fig. 2).

The mansion vividly reflects the Royalls’ wealth and has long been recognized as an outstanding early example of Georgian residential design in New England. The public rooms on the entry floor and the three main bedchambers on the floor above feature elaborately carved woodwork, window seats, and fireplace surrounds of European tile (Figs. 3, 4). We know from probate inventories that the house was expensively furnished: in the “best room,” the japanned tea table set with imported porcelain would have shone against the backdrop of highly polished mahogany and walnut tables and chairs. Items unearthed on the property by archaeologists included wine bottles embossed with the Royall family crest, wine glasses with air-twist stems, and a delicate china chocolate cup.

The mansion’s service corridor features a narrow staircase that winds from basement to attic, linking the storage, work, and sleeping spaces used by those enslaved as they tended to the needs of the Royall family. These rooms notably lack the decorative flourishes that characterize the spaces inhabited by the family and their guests. At least eight “Negroes Beds and beding” were located in the so-called Winter Kitchen and the chamber above it at the time of Isaac Sr.’s death in 1739 (Figs. 5, 6).

Around 1760, a simple and nearly windowless clapboard addition more than doubled the size of the brick “out kitchen,” creating what is known today as the Slave Quarters (Fig. 7). The first floor of the addition—located just thirty-five feet from the mansion—was originally divided into three narrow rooms, each with a door opening onto what was then a cobblestoned courtyard. Extensively renovated soon after the site was purchased by the nonprofit organization in 1908, the space is now used for public and educational programs. The museum’s long-term goal is to restore the building for the interpretation of its original purpose.

Royall Jr. supported the Patriot cause in the debates that preceded the start of the American Revolution. But as soon as the British Redcoats and Colonial Minutemen exchanged fire in Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, he fled to Canada and then to England. His actions may have reflected latent Loyalist leanings, but his former friends believed he acted out of fear rather than conviction. During the war, his estate was used by American commanders, including General George Washington.

When Royall died in England in 1781, his will revealed his plans for the enslaved Africans he still held in Massachusetts, including a woman known as Belinda Sutton, enslaved in Ghana at the age of twelve and now in her sixties. Royall’s will offered her the choice of continued enslavement, in the household of his daughter, or freedom, “provided that she get Security that she shall not be a charge to the town of Medford.” Belinda chose freedom.

When the promised “security” was not forthcoming, Belinda appealed to the state. Illiterate, she signed an “X” on a petition, written by one of Boston’s black activists. The petition poignantly recounts her life from her childhood capture in Africa, where she had enjoyed a life of “compleat felicity,” through the fifty years she had been compelled to “ignoble servitude for the benefit of an Isaac Royall.” Belinda pleaded for an allowance from Royall’s estate, arguing that she had been denied “the enjoyment of that immense wealth, a part whereof hath been accumulated by her own industry and the whole augmented by her servitude.” The Massachusetts Legislature awarded Belinda fifteen pounds annually. With annual payments regularly missed, she renewed her claim five times in the next decade. The remainder of her life is, sadly, lost to history.

The timing of Belinda’s 1783 petition grants it a historical significance even beyond her remarkable narrative. For more than a decade, groups of Boston’s enslaved and free Africans had petitioned authorities for an end to slavery, claiming that the enslaved “have in common with other men a natural right to be free.” Only two months after Belinda submitted her petition, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court relied on the promises of freedom and equality in the new state Constitution to effectively abolish slavery. But as Belinda’s petition reveals, freedom was also a perilous state, which those newly freed—particularly the elderly and infirm—often faced without any means of support.

The Royall House and Slave Quarters is dedicated to ensuring the “rediscovery” of Northern slavery through the lives and artifacts of Belinda and others whom the Royalls enslaved. This unique museum—staffed largely by volunteers—offers enlightening tours and enriching programs for adults and students. It is committed to educating the next generation to have a deeper understanding of the North’s significant direct involvement, ongoing complicity, and economic investment in American slavery, and the many ways in which those actions have shaped our nation. Believing that its distinctive mission justifies big ambitions, the organization seeks the resources necessary to accomplish them. For more information about the museum and ways to support its educational mission, visit www.royallhouse.org or call 781.396.9032.

The Royall House and Slave Quarters is located at 15 George Street, Medford, Massachusetts. The museum is open to the public for tours on weekends from June through October, while school and group tours are available from mid-March to mid-November.

-----

Michael A. Baenen, Barbara F. Berenson, and Gracelaw Simmons are members of the Royall House and Slave Quarters Board of Directors.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.