Theodore Wendel

Ipswich Impressionist

Of the more than fifty years of Theodore Wendel’s (1859–1932) mature career as an Impressionist, thirty-four were spent in Ipswich, Massachusetts. There, in the town itself and, later, in the surrounding farmlands, he established a family, painted outdoors day and night, and fine-tuned his innovative style (Fig. 1).

Born in Midway, Ohio, Wendel trained at the McMicken School of Design of the University of Cincinnati and the Royal Academy in Munich (1878–1879). In the summer of 1879, he went to Polling, Bavaria, where he joined the charismatic Frank Duveneck, becoming one of the group of young American painters known as the “Duveneck Boys” who painted with Duveneck in Germany and Italy. A return to Ohio in 1881 and a stint of teaching in Newport, Rhode Island, only encouraged Wendel to seek more training abroad.

He subsequently enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris (1886–1887) and, during the summers, helped to found the first colony to paint alongside Claude Monet in the tiny French village of Giverny. Here Wendel’s style evolved from the dark, richly layered canvases of the Munich School, mostly figural and portrait subjects, to landscapes, first of soft grays and greens evoking the international school of Tonalism, and finally, to full-blown Impressionism, often demonstrating a love of compositional experimentation. His first works exhibited in America after the Giverny summers were highly praised, one critic even proclaiming Wendel as the “earliest of the Boston Impressionists to handle the Monet style with effect.” 1

With his return home, the most productive period of Wendel’s career began. Five solo and fourteen group exhibitions were added to his resume in the next decade. French themes were gradually replaced around 1890 by domestic ones, particularly those of Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he was painting and sometimes teaching. It was while an instructor at the Cowles Art School of Boston that Wendel met his future wife, Philena Stone, a student of the school. An accomplished pianist and member of a prominent Ipswich family, she appears in Wendel’s 1897 Artist’s Wife in a Hammock (Fig. 2), fashionably dressed in summer whites and straw hat. The couple was married that same year and, after an extended honeymoon abroad, settled in Ipswich for good.

Then, as now, Ipswich had the look of an old New England village, complete with winding roads, stone fences, a town green, and steeple-topped churches. The artist didn’t stray far from his home, a small Victorian house at what is now 28 County Street, to seek out subjects for his canvases. Works with obvious Ipswich titles began appearing around 1900 in Wendel’s submissions to major national exhibitions.

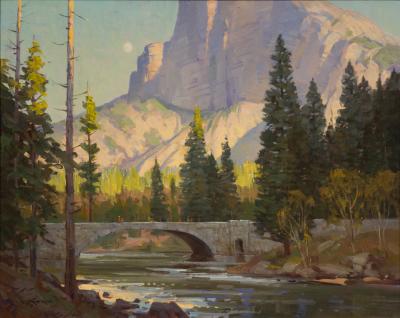

Within a short distance of his home, the County Street Bridge, its double-arched stone foundations allowing passage over the Ipswich River at one of its narrower points, was a favorite site for the artist. A painting of the bridge (Fig. 3) demonstrates the same compositional inventiveness that Wendel sought in his Giverny scenes. A high horizon line serves to focus the viewer’s eye in the picture’s design elements, a horizontal band of the upper walkway reflected in the water below. The same holds true for the arch of the bridge, which, when mirrored in the river, forms a full oval through which we glimpse a more traditional river vignette, as if to contrast the old and a new vision. Along the upper border of the canvas, a line of willow branches stream down unevenly, allowing snapshots of three figures crossing the bridge on foot and, below, a couple rowing in a small dory. This human activity reinforces that of the energy of the foreground rapids, which would have fed the old sawmill on the site.

Two extant Ipswich paintings feature the First Parrish Church, with its red spire glowing in the sunlight. In Sledding, Ipswich, Mass. (Fig. 4), several small children, perhaps Wendel’s own among them, are seen trudging up the favorite “sledding hill” of the town. Winter Sunlight (not shown) is a nearly identical scene, though with a different vantage point and without figures, flooded in a golden afternoon haze.

To the north of his home on County Street and a right turn on Green Street, stood the county jail, which also served at times to house the town’s indigent families. Wendel painted the formidable building in Old Jail House, Ipswich (Fig. 5). Once again, an Ipswich landmark is not the main focal point of the painting, its long brick structure and high chimneys punctuating a scene of mostly fruit trees and even taller oaks in full summer bloom.

A rich palette of pale green, yellow-gold, and beige pigment, applied in Impressionistic strokes, is clearly meant to complement the red-orange of the jail’s façade that appears in patches through the limbs of the trees.

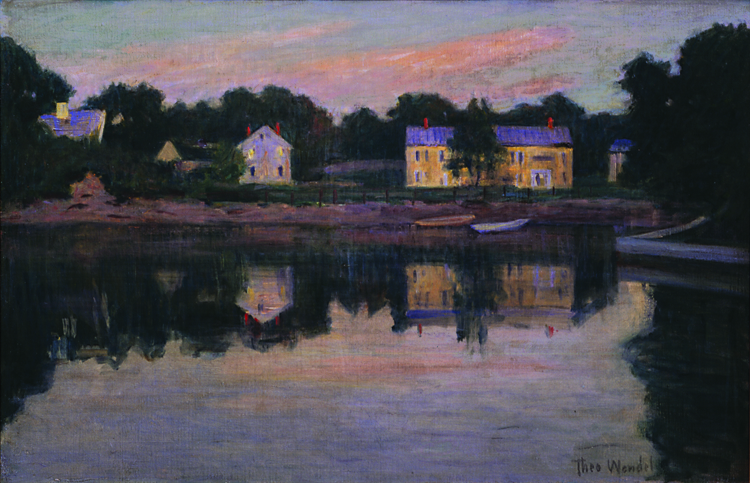

A rare evening subject is a painting now called Twilight on the Ipswich Marshes (Houses on a Pond) (Fig. 6), which may be a view of the Great Cove, a large bulge in the Ipswich River adjacent to the stretch of land that held the county jail. Once a bustling scene of shipbuilding and the town’s Heard distillery until the early 1800s, in Wendel’s time it was a much quieter place. Again, there is no foreground toehold, and the canvas divides almost symmetrically, with water below and buildings and sky for the upper half. Utilizing the mirror image of the houses and trees reflected in the water was a favorite compositional technique for Wendel. Along with the deepening hues of nightfall, the dark foliage and isolated buildings on the opposite shore create an atmosphere of deep melancholy.

From the vantage point of the Great Cove and the old jail, Wendel could catch a distant glimpse of the other major bridge in town, the Green Street Bridge. Bridge at Ipswich (Fig. 7) is undoubtedly Wendel’s masterpiece, the epitome of the New England fall scene. The entire canvas celebrates the hues of the season, not only in its natural elements but in those of human construction as well. The pale yellow, pink, and gold tones of the bridge itself are repeated in the tightly nestled houses in the distance. Perched on the Turkey Shore Road side of the bridge, Wendel incorporated in his view the Green Street transit over the bridge and its offshoot, Water Street, which winds its way north along the opposite bank. The slope of the sparsely populated Town Hill is backed by a pale pink and blue cloudy sky. Wendel included the mode of transportation of his day: two men on foot at the right and a horse and wagon posed midway on the bridge.

Moving north along the river and Turkey Shore Road, Wendel could look across the lawns of the town’s wealthy homeowners to the colorful dories of the fisherfolk and their picturesque clam shanties, where tools for digging and cleaning the clams were kept. Lower River, Ipswich (Fig. 8) captures that scene. The shedding birch tree at the left introduces another of the artist’s brilliant autumnal pictures, with golden yellow and orange grasses lining the waterway. Between these vertical framing elements, a young boy pulls up to the bank in his dory, one of many included in the foreground and opposite shore. The winding path of the river pulls the viewer around the cove and into the distance, guided by colorful swaths of grass.

At about the same time that Wendel and his wife lived at County Street, they also spent time during the warmer months at another property inherited from Philena’s family, called the “Lower Farm,” located at what is now 161 Argilla Road, two-thirds of the way from the town to Ipswich Bay. The glacial peninsula on which the site exists afforded the artist extensive views of the surrounding marshes, hills, and meadows, including landmark drumlin islands and beaches.

From the Lower Farm Wendel’s choice of subjects was endless. In one direction, he had a spectacular view of the marshes and water. In another sweep, he could take in the rolling hills and farms upland from the marshes. One such scene is Early Autumn (Fig. 9), now called Goldenrod and Asters (Field of Flowers), which was first shown in 1909. All of the angles within the picture—of the hills, the rock formation, and masses of brilliant golden rod and purple lupines—lead to the central focus of Wendel’s children: Mary, then about seven years of age, and Daniel, at about five; their youth reflected by the young birch with twin trunks nearby. At the right, the ever-present haystack is a reminder of the means of livelihood for most of the inhabitants of the region.

A familiar subject along the shore was the harvesting of salt marsh hay, with teams of oxen or horses tediously hauling the wagonloads to elevated wooden “straddles,” awaiting transfer to the barn as winter feed for the animals or, if in abundance, shipped as far as Boston. Wendel’s Old Bridge, Ipswich (Fig. 10) shows such a scene of a team and hay wagon trudging across a long, swaying bridge over the marshes. The line of delicate locust trees would have served either as a wind shield or may have marked the borders of the farmer’s property. Philena’s father, Asa Pease Stone, had farmed the marshlands successfully until his death in 1892, in the days when the fields were still cut by hand with a scythe.

The Ipswich marshes made for spectacular, colorful settings to place the figure, as in Woman by the Sea (Fig. 11), possibly an image of the artist’s wife strolling at the point where the salt hay field meets the tall grasses and purple lupines. Rich green bands of color, layer upon layer into the distance, are made up of vertical brushstrokes, interspersed with daubs of violet, patches of red flowers, and the occasional clumps of trees.

By the time the Wendels sold the Lower Farm in 1915, they had already set their sights on another parcel of land they called the “Upper Farm,” further upland and closer to Ipswich village, at what is now 89 Argilla Road. Now the artist had another set of vistas to choose from. The house on the forty-acre Upper Farm had two distinct personalities: the front of the house, with its double-tiered entrance, was that of a town residence (Fig. 12), while the rear (Fig. 13) shows the rugged aspect of a farmhouse, complete with a large vegetable garden.

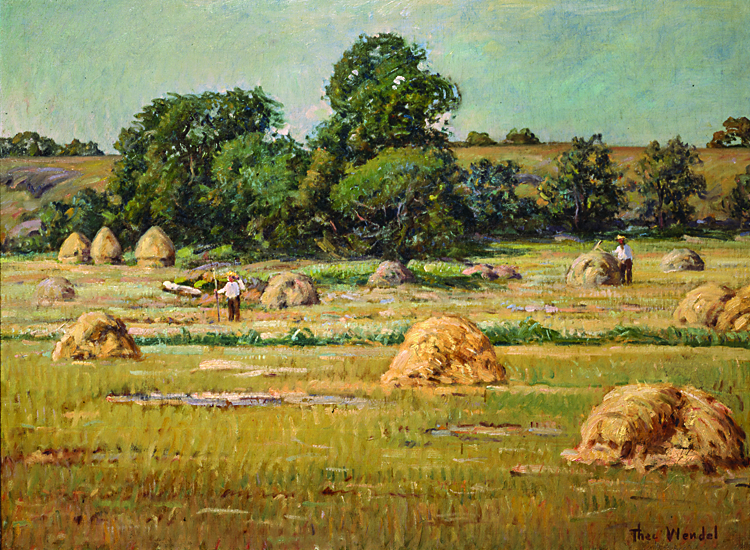

Haying (Fig. 14) captures the essence of farm life. The loose hay is being stacked by laborers with pitchforks into “cocks” that looked like “pointed hats,” according to Kitty Crockett Robertson in her memoirs of growing up on Argilla Road. “It was when the hay was in cocks that the farmers worried and watched the sky to the north for the approach of the black thunder clouds, heavy with wind and rain—or they looked to the east for a ‘sea turn,’ the shift of the wind to the northeast and the accompanying rain and fog that might last for days, while the hay blackened with mildew and spoiled.” 2 In Haying, however, the brilliant sunlit meadow seems the epitome of optimism.

Many of Wendel’s later works demonstrate his ability to celebrate trees of all species, working their colors and distinctive shapes into a harmonious whole. An Old Orchard, Ipswich, Mass. (Fig. 15) features a favorite motif of fruit trees in glorious bloom, dwarfed by taller willows and perhaps varieties of ash and hickory, although red oaks, white birches, and the vanishing elm were also germane to the region at the time. These trees were valued for their protection from the harsh winds coming off of the marshes. The view in An Old Orchard may be of the sloping terrain of Heartbreak Hill, directly across the road from the site of the Upper Farm. The artist painted all aspects of its wooded slopes, from head-on views to those from the crest, from which he could look all the way to Town Hill and the village of Ipswich and, in the other direction, to the marshlands and water.

A year before Wendel’s major one-person exhibition at the Guild of Boston Artists in 1918, he was stricken with a severe infection of the jaw, and, although his physical powers were restored, the couple spent the next few years in Boston (1919–1921), where he rented a studio and, most likely, reconnected with his old artist friends of the Munich and Gloucester years. The family continued to return to Ipswich in the summers and perhaps for Theodore Wendel’s final years. One obituary reported that the artist had died “at his home” at 23 High Street, Ipswich.3 Another reviewer, stating that Wendel “had not been in good health for several years,” called him “one of the best known American landscape painters.” 4

Laurene Buckley, Ph.D., is executive director of the Susquehanna Art Museum, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. She is the author of Joseph DeCamp: Master Painter of the Boston School (1995) and Edmund C. Tarbell: Poet of Domesticity (2001).

2. Kitty Crockett Robertson, Measuring Time (Ipswich, Mass.: Bookcrafters, 1981), 107–108.

3. “Obituary,” Boston Herald (December 20, 1932): 32.

4. “Ipswich Services for Theodore Wendel: Widely-Known American Landscape Painter,” Boston Globe (December 21, 1932): 2.

![Fig. 12: Theodore Wendel’s (1859–1932), Upper Farm house [front view with porch], ca. 1912. Photograph, Wendel family scrapbooks.](../sites/uploads/0121.jpg)

![Fig. 13: Theodore Wendel (1859–1932), Upper Farm house [rear view], ca. 1912. Photograph, Wendel family scrapbooks.](../sites/uploads/0131.jpg)