Top Museum Acquisitions: 2015 in Review

The year 2015 was one of general optimism for the museum community. New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art left its Madison Avenue location and opened its Renzo Piano-designed new home in the hip “Meatpacking” District, offering expanded and more convenient hours. Future building plans in Manhattan include MoMA’s $93 million expansion of its 11 West 53rd Street space into the neighboring lot once occupied by the American Folk Art Museum (now refocused at Lincoln Center); stay tuned. On the West Coast, the Broad opened its doors in downtown Los Angeles in September, and, in October, the Columbus Museum of Art opened its new Margaret M. Walter Wing. The Milwaukee Art Museum held its grand reopening in November after a six-year, $34 million renovation and reinstallation of its galleries.

As part of the expansions, re-hangings, and reinventions within institutions, museums are also looking for new ways to reach audiences through partnerships and online collections access. The Phillips Collection and University of Maryland are partnering to transform scholarship and innovation in the arts. Both the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Indianapolis Museum of Art have made thousands of works available for download, providing open access for personal, scholarly, or commercial use. Bloomberg Philanthropies committed $17 million to six museums to increase engagement and education through technology; they include the Brooklyn Museum, Cooper-Hewitt, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Other museums that have received grants to digitize portions of their collections include the Amon Carter Museum, New Hampshire Historical Society (textiles), and the Peabody Essex Museum’s Phillips Library; The Warhol and MoMA have joined forces to convert hundreds of Andy Warhol’s films to digital files. The National Gallery of Canada is utilizing new scanning and 3-D printing techniques so art can be “shared” and experienced on new levels. Winterthur Museum received a grant to map and record its garden, providing online access to its historic “living” collection.

All things don’t always go according to plan, however, and the year 2015 also saw the closing of several museums across the country. These include the Gene Autry Museum in Oklahoma, the Museum of Biblical Art in New York City, and the National Children’s Museum in Washington, D.C., all the result of financial woes. Meanwhile, complications led enlargement plans by both the Frick Collection in NYC and the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh to be dropped. An initial San Francisco location for George Lucas’ Museum of Narrative Art fell through but Chicago recently approved the plan. San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum and the Santa Monica Museum of Art are among those in search of a new home; the latter focusing on pop-up exhibitions in the meantime. Looking around, however, one sees many museums thriving and acquiring new objects for their permanent collections.

The year 2015 was a big year for the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, made possible in large part from a gift of American art from James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin—valued in excess of $200 million. In 2010, a wing was added to the museum in their name, in which a new acquisition by Benjamin West was recently installed, Portrait of Prince William and his Elder Sister, Princess Sophia (Fig. 1). Referred to as one of “the most valuable acquisitions in VMFA history,” King George III commissioned the portrait in 1779. West’s portrait depicts the eldest children of William Duke of Gloucester, brother of the “Mad King.” The work entered the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through the J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art.

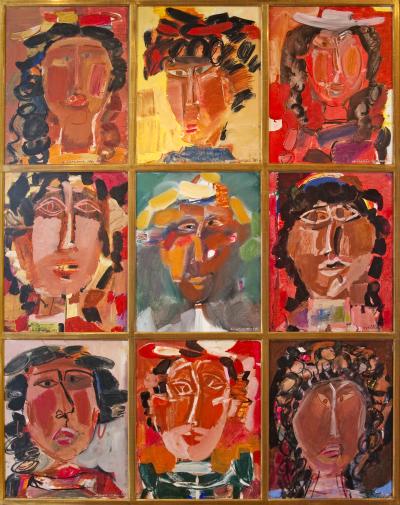

Works by Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas (1899–1979) are on many museums’ wish lists, and both The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art were able to acquire one. The Met purchased the circa-1934–1939 Let My People Go (Fig. 2), while the National Gallery scored the 1939 The Judgment Day. Both works were bought from a private collector who had purchased them from the artist.

The Frick Collection in New York City acquired a sixteenth-century French ceramic pitcher (Fig. 3), likely from the Saint-Porchaire factory in France, which had been owned by the French branch of the celebrated Rothschild banking family. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston was the recipient of a collection of 186 objects—European decorative arts, drawings, paintings and prints—originally owned by Baron and Baroness Alphonse and Clarice de Rothschild of Vienna, members of the Rothschild family, donated by their heirs to the museum. A year-end acquisition from the Ann and Gordon Getty Collection was of a rare eighteenth-century desk and bookcase from Mexico (see pages 210–211). Among the other acquisitions was a circa 1770-1775 silver coffee pot (Fig. 4) and creamer from Guatemala. The forms and chased decoration, which emulate English design, are a rare counterpoint to the ubiquitous ecclesiastical Catholic silver of Latin America.

The Art Institute of Chicago has been “historically poor in collections of classic pop art,” according to the museum’s curator of contemporary art, James Rondeau, but a gift of forty-four Pop and postwar art—including ten silkscreens by Andy Warhol, three Jasper Johns paintings, two Roy Lichtenstein canvases (Fig. 5), four Gerhard Richter paintings, and a Cy Twombly sculpture— from Chicago art collector and retired plastics mogul Stefan Edlis and his wife Gael Neeson, has changed that. The works are estimated to have a combined value of more than $500 million. The Art Institute has also been pledged almost four hundred pieces from the collection of Buddhist ritual objects and Asian ethnic jewelry of local business executive and life trustee Barbara Levy Kipper.

The Dallas Museum of Art has purchased objects in a variety of categories, including a Guatemalan ceramic vase (A.D. 700–900) previously owned by the Archaeological Institute of America; a marble head of Herakles (A.D. 100) from a Sotheby’s antiquities sale; and a seven hundred-piece jewelry collection once owned by Viennese gallerist and collector Inge Asenbaum and acquired by Dallas philanthropist Deedie Potter Rose as a gift for the museum. The works were created by more than 150 acclaimed modern studio jewelers, including Frank Bauer (Fig. 6), Georg Dobler, Emmy van Leersum, Fritz Maierhofer, Hermann Jünger, Daniel Kruger, Claus Bury, Peter Skubic, Francesco Pavan, Gert Mosettig, Anton Cepka, and Wendy Ramshaw.

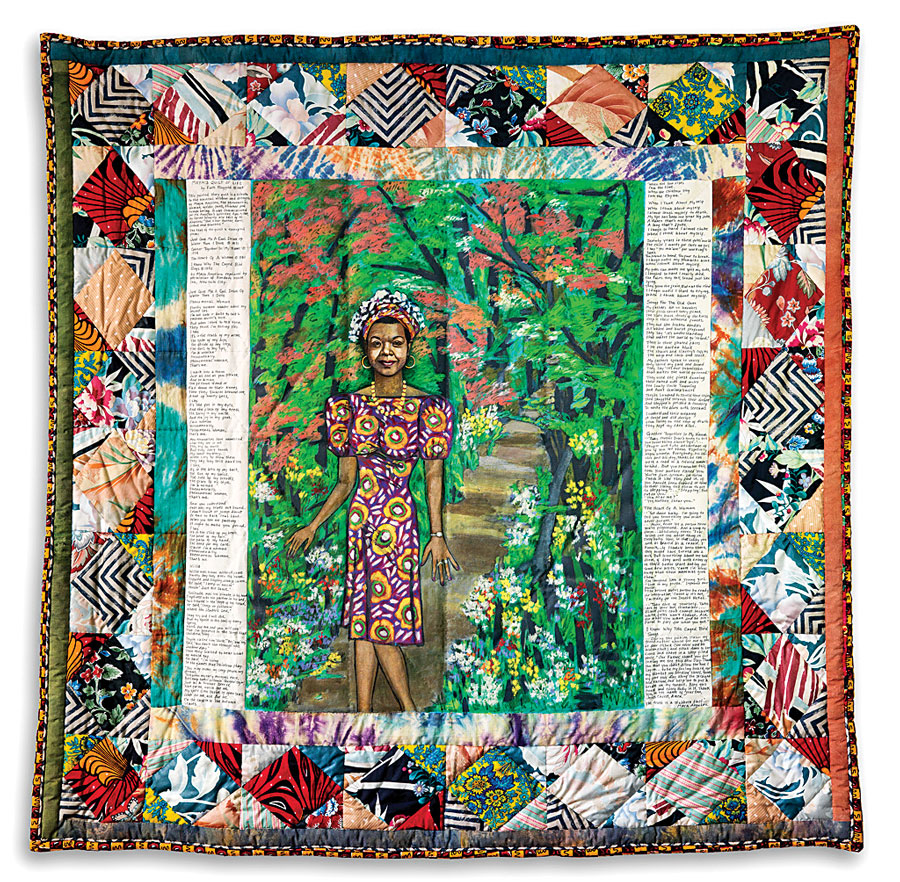

Another active buyer in 2015 has been the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, which purchased from an auction of the late poet Maya Angelou’s art collection, a painted quilt, Mayas Quilt of Life (Fig. 7), by Faith Ringgold (for $461,000), as well as two sculptures, Maman (1999, bronze, stainless steel, and marble) and Quarantania (1947–1953, bronze, painted white with blue and black, and stainless steel), and two paintings, Connecticutiana (1944–1945, oil on wood) and Untitled (1947, oil on canvas), by Louise Bourgeois, and a wall-mounted sculpture, Silver Upper White River (2015), by Maya Lin.

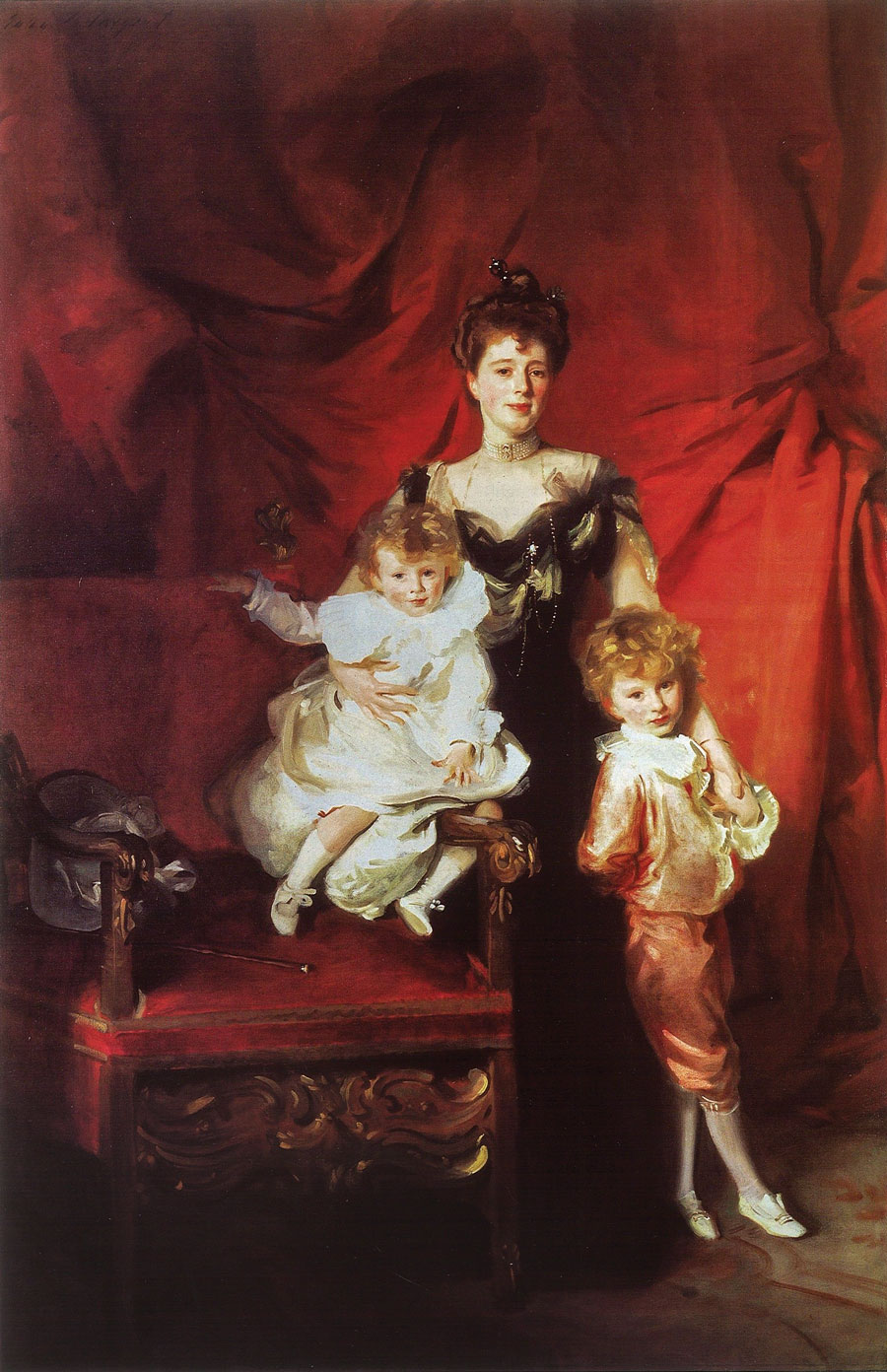

The Asian Art Museum of San Francisco received a gift from a San Francisco couple, Phyllis Kempner and David Stein of nineteen works by contemporary Japanese and Korean ceramicists (Fig. 8). For its fiftieth birthday in 2015, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art received many presents, including an eight-foot-tall oil portrait (Fig. 9) by John Singer Sargent of Mrs. Cazalet and Children Edward and Victor (1900–1901), a promised gift from Barbra Streisand. (For fans of Sargent, the MFA, Boston, established the John Singer Sargent Archive, formed with a 2015 gift of letters, photographs, and sketches that document the artist’s life and work. The gift was given by Sargentr’s grand-newphew, Richard Ormond, his wife, Leonée, and Jan and Warren Adelson.) Also in honor of its 50th—with funds from Kelvin Davis and a partial gift from Christine Jones Janssen—the museum purchased an eighteenth-century painting by Miguel Cabrera, considered the most notable artist of his time in Mexico City. From Spaniard and Marisca, Albino reveals the intense interest in interracial marriage at the time. As unusual as the painting’s subject is the location it had been kept in for years—rolled up under a sofa in a Bay Area home. The painting was in good condition and, after some sleuthing, its identity was discovered.

A number of museums received or purchased European works of art. Among them the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. The museum acquired a work that had been lost since 1882, Study of a Young Man, circa 1760, by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, the most acclaimed painter working in Paris at the time (Fig. 10). Among the renovations at the Milwaukee Art Museum was its expanded European galleries. Long an important center for the study of German art in America, the museum’s German Romanticism collection was strengthened with its acquisition of the sensitively painted 1872 Mother of the World (Fig. 11) by Franz Ittenbach. It was one of many acquisitions celebrating the reimagined galleries. Among the discoveries visitors will make is the newly inaugurated 16,000-square-foot Constance and Dudley Godfrey American Art Wing. Within the wing are five galleries curated by the Chipstone Foundation, which is dedicated to interpreting the decorative arts in innovative ways. Chipstone recently acquired a hitherto unknown Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Queen Anne cherry talk clock (Fig. 12) from Pook & Pook auctions for $192,000. Dated 1762 and with dial inscribed Rudy Stoner, the case is embellished with mixed hardwoods, pewter inlay, and some of the most exquisite and sophisticated engraving seen on an American colonial tall clock. Says furniture historian and consultant Alan Miller, “The clock is an architectural fantasy and features the most astonishingly original and beautiful Baroque hood ever made in America.”

The U.S. museum that has perhaps accessioned the most artworks for its permanent collection this year is the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. As a result of its 2014 merger/takeover of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, it has acquired approximately eight thousand pieces—including works by American artists Henry Ossawa Tanner, Betye Saar, Thomas Downing, Joshua Johnson (Fig. 13), and Howard Mehring; French artists, Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, Honoré Daumier; Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens, and Dutch painter Meindert Hobbema. Among the St. Louis Art Museum’s purchases was Sunday Morning Breakfast by Horace Pippin for $1.2 million (Fig. 14). Other acquisitions included Mariam Ghani’s The City & The City video, Soundsuit by Nick Cave, and a chrome 1935 table lamp by Harris Armstrong.

Looking ahead, some trends are emerging. The first involves African and African American art: The Smithsonian will open a National Museum of African American History and Culture next year, while the Brooklyn-based Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts is in the process of moving to a larger space within the borough, and the Baltimore Museum of Art recently opened renovated and expanded galleries for African art. The Studio Museum of Harlem is planning a new, larger building for its collection, and a retired phone company executive with a multi-million dollar collection of African art, Eric Edwards, is looking to open his own African art museum.

- Fig. 14: Horace Pippin, American (1888–1946), Sunday Morning Breakfast, 1943. Oil on fabric, 16 x 20 inches. Saint Louis Art Museum, Museum Funds; Friends Fund; Bequest of Marie Setz Hertslet, Museum Purchase, Eliza McMillan Trust, and Gift of Mrs. Carll Tucker, by exchange (164:2015). Image courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York.

Additionally, a growing number of museums have begun to allow visitors to look at their objects in storage. Among them are, the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Daytona Beach, Florida, London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, the Strong Museum in Rochester, New York, the Brooklyn Museum, The Metropolitan Museum and, most recently, the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. Referred to as “visible storage,” these displays reflect the fact that many museums are only able to exhibit a tiny fraction of their holdings.

-----

Daniel Grant is a freelance writer specializing in the arts industry.

This article was originally published in the 16th Anniversary (Spring 2016) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on www.afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and afamag are affiliated with InCollect.

©-Heirs-of-Aaron-DouglasLicensed-by-VAGA,-New-York,-NYf.jpg)

-2015.15_.jpg)