Treasures from Olana: Landscapes by Frederic Edwin Church

This archive article was originally published in Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Olana, in New York state’s Hudson Valley, is the spectacular former home of Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), the most renowned painter of the Civil War era and the leading artist of the second-generation Hudson River School. Built in 1870–1872 on an Italian-villa plan modified by Islamic detailing and decoration (Figs. 1, 1A), Olana was intended to be both a home for the artist and his family, and a museum to his work. The house is filled with the Oriental bric-a-brac that Church collected on his travels to the Near East and Europe between 1867 to 1869, just before he began construction of Olana. The exotic décor and accessories can distract from what are undoubtedly the house’s primary treasures: the paintings, oil sketches, and studies by Church, many of which he framed expressly for display on the walls. Thanks to Church’s son Louis (1870–1943) and his wife, Sally (1868–1964), who lived at Olana until their deaths, the house and grounds were preserved much as the artist originally fashioned them.

Chartered in 1966 and owned and operated by the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, the house has been open to the public since 1967. In 1971, The Olana Partnership, a nonprofit, was created to provide support for the site. In 2005 and 2007, while a fire protection and climate management system were being installed in the house, Treasures from Oland: The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church, a selection of eighteen paintings, circulated from the site to six museums and public galleries throughout the United States. At certain venues, other works by Church augmented the selection. This archive article presents themes from the traveling exhibition.

A pupil of Thomas Cole (1801–1848), the founder of the Hudson River School, and a devotee of the natural history texts of Alexander von Humboldt, the eminent German naturalist, Church made it his ambition to range beyond the scenery of North America and Europe, where Cole had traveled, and to explore internationally the disparate habitats of the earth, which he recorded and then interpreted on an expansive pictorial scale. In the 1850s he twice visited the humid jungles, temperate Andean valleys, and frozen summits of Colombia and Ecuador, and in the same decade sailed north near the Arctic Circle to sketch icebergs. A devout Presbyterian, Church brought his wife and family to the Near East in 1868, where he traced the Judeo-Christian history in the landscape of Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, and afterwards toured much of Europe. In the heyday of his career, about 1855 to 1875, he produced outsized paintings of those locales—as well as spectacular pictures of his native countryside in New York and New England—several of which he toured almost like theatrical events; using elaborate framing and draping, carefully managed lighting, and descriptions of each work that encouraged viewers to explore vicariously the regions depicted. The Heart of the Andes (1859; 66 x 120 inches; The Metropolitan Museum of Art), the largest and most talked-about of all his works, was shown to crowds in New York (twice) and seen in seven other American cities, as well as London and Edinburgh.

Church’s patrons paid him great sums for such paintings and he amplified his earnings by admission receipts to the exhibitions and the sale of engraved reproductions. To his growing income he added loans from his father, Joseph Church, a prosperous businessman from Hartford, Connecticut (where Frederic was born and raised) in order to purchase land near Hudson, New York in 1860. The property overlooked not only the Hudson River but also the house of his former master, Thomas Cole, in Catskill village, in the shadow of the mountains where pupil and teacher wandered and sketched together in the mid-1840s. After the Civil War, Church purchased hilltop property adjacent to his land and, on his return from his trip to the Old World in 1869, began building the Persian-inspired house that would become Olana. In 1872 the Church family moved in, but Frederic continued to refine and improve the house virtually until his death.

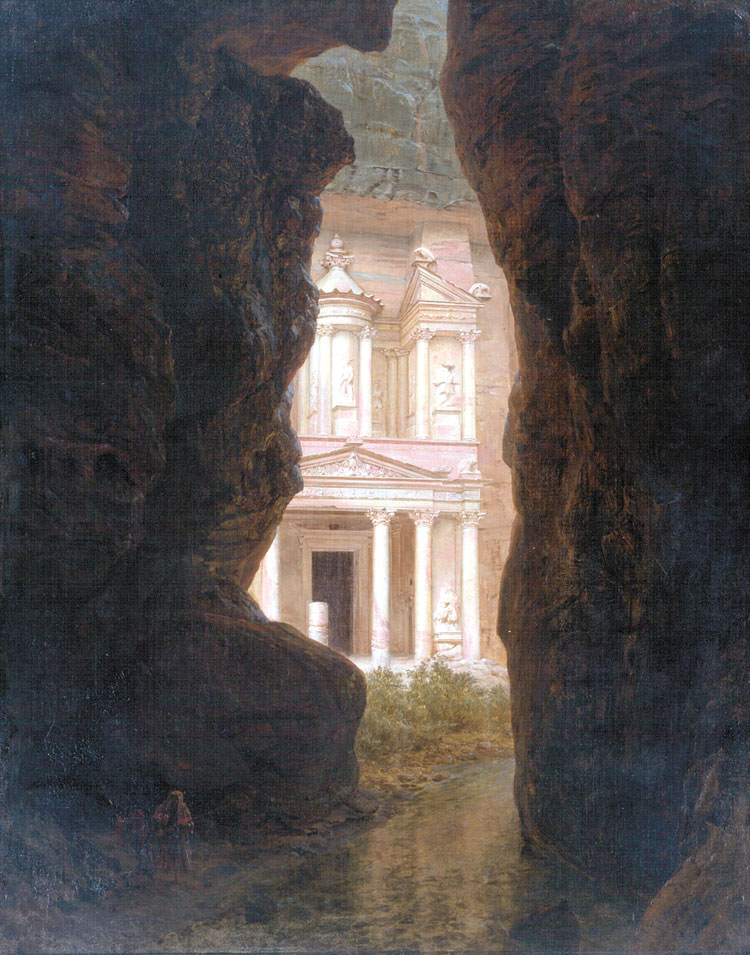

In 1875, he installed El Khasné, Petra (Fig. 2), the most important painting at Olana, over the ogee-shaped fireplace in the sitting room (Fig. 3). It was a gift to Isabel, who had been unable to accompany her husband on his excursion from Beirut to the ancient rock city of Petra in February 1868. “El Khasné” is Arab for “treasury,” the name given to the building by Bedouins who believed it had once held the riches of Egyptian pharaohs. El Khasné, with its little stream flowing by the foot of the façade, was a metaphor for Church’s castle on the hill, with the Hudson River running by its base. Indeed, Church’s exalted view of his home—in his own words, “the Center of the World”—is evident in the oil sketch (Fig. 4) he made in August 1872, just before moving in, of Olana’s tower visible among massive, lofty thunderheads.

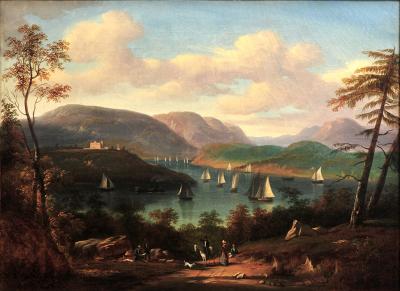

Such cloud depictions were part of the standard vocabulary of the Sublime (i.e., the awesome or fearsome in nature) aesthetic that Church had admired in the paintings of his teacher, Cole. From the neighborhood of Cedar Grove (Cole’s house and now also an historic site, operated by the Greene County Historical Society and the Cedar Grove Board of Governors), the nineteen-year-old Church painted a modest yet astonishingly lucid picture of the prospect that his teacher had made renowned: the view over the Catskill Creek to the eastern range of the mountains, including the dolphin-backed profile of Kaaterskill High Peak (Fig. 5). Cole once confessed—perhaps with as much envy as admiration—that his student possessed “the finest eye for drawing in the world.” Though a painting, Catskill Creek readily verifies the master’s words, and looks forward in both design and execution to several of the fastidiously wrought yet grand views and compositions of the North American, especially New England, landscape that Church would produce within the next decade. Paintings such as this established Church’s name among the New York community of landscape painters and patrons he joined in the late 1840s.

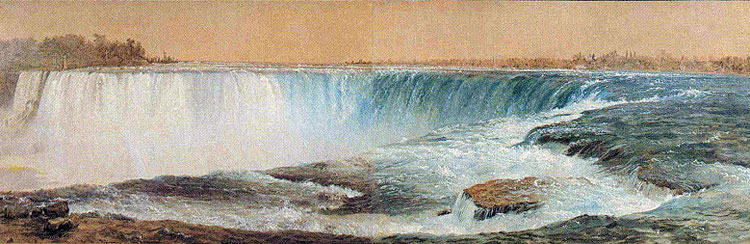

The exhibition of his seven-foot panorama, Niagara (Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), in a private gallery on Broadway in 1857 marked the beginning of Church’s national and even international reputation. The most famous natural landmark in America, Niagara was a hackneyed subject for artists even then. Yet Church found a way to see it afresh—even frighteningly—by stepping to the edge of the driving Niagara River and, for the effect of the picture, forgetting the foreground and forcing the viewer to contemplate the volume of water rushing irresistibly toward the fall. Except for raising the height and embellishing the sky in the finished painting, Church altered very little of the composition of the original oil study (Fig. 6) for Niagara. That he framed the study for display in his sitting room suggests his recognition of the work’s significance to his career.

The most spectacular of the North American pictures of his early career were of the sunset or twilight sky, culminating in his masterpiece, Twilight in the Wilderness (Cleveland Museum of Art), exhibited in 1860. As impressive in its way, though, is a sketch of a fleeting sunset (Fig. 7) that the artist made probably several years earlier in Maine. In it the horizon is divided into contiguous yellow and pink zones—caused by some atmospheric refraction of the sunlight beyond the distant hills. He bridged the color passages with streaming stratus clouds singed orange by the submerged sun’s fires, while higher wisps of cirrus await ignition. If Church did not depict this view on the spot, he surely recorded it while it was still warm in his memory.

Church cemented his reputation with his South American subjects, many painted on a monumental scale. The current exhibition includes his study for The Heart of the Andes, and a haunting twilight portrait of Mount Chimborazo, the snow-covered dome seen in the background of that great painting. Some of the artist’s most dazzling tropical sketches in oil were made years later in Jamaica, where he and Isabel had fled with friends in the summer of 1865, after they lost their first two children to diphtheria within days of one another. The devastated couple parried their grief in related ways: Isabel collecting ferns with an earnestness bordering on the “insane” (according to Church), and he focusing on botanical studies such as Tropical Vines and Trees, Jamaica (Fig. 8). The effect of the study is both wondrous and oppressive. Church seems not to have missed a single leaf among the hillside vegetation as it rises relentlessly towards the sun, yet appears smothered by the trailing vines. Frederic’s and Isabel’s complementary pursuits in their paradisiacal refuge helped summon their faith in regeneration. Returning home to Hudson, Isabel gave birth soon after to Frederic Joseph in September 1866; three more children followed by 1871.

Sunset, Jamaica (Fig. 9), may be the ultimate testimony of Church’s retreat to the island with his wife. The changeable weather they experienced there made for spellbinding sunsets and twilights comparable to those that had inspired him in North America. Some, if anything, were even more explosive or turbulent in effect. He later confided to his father: “I might not see similar again.” Naturally, therefore, he recorded a few, none more disquieting, even divine, in effect than the bursting radiance he witnessed over the ocean from Jamaica’s Blue Mountains in July 1865. Whatever the spectacle may have meant to Church at the time, two years later it assumed unmistakable memorial overtones when he amplified and concentrated its effect in a large painting suggestively titled The After Glow. Even as he worked on it, his cherished sister Charlotte succumbed in Hartford to a long illness, and his father purchased the painting later that year, 1867. Eventually, with the deaths of his father and another sister, the painting returned to Church at Olana, where it still hangs. Impressive as the large picture is, the oil study, with its airier foreground and middle distance and remote ocean horizon, retains more of the revelatory flavor of the artist’s first notice.

The retreat and reaffirmation sought in Jamaica were extended and perhaps fulfilled during the Churches’ sojourn in the Holy Land from 1867 to 1868. Isabel, her mother, and the couple’s toddler, Frederic Joseph, accompanied the artist, and while the family was abroad, another son, Theodore Winthrop was born in Rome in winter 1869. In Palestine, husband and wife pursued biblical archaeology, visiting the sites of the Old and New Testaments, and the artist collected sketch material for major pictures such as Damascus (1869; unlocated), Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives (1870; Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), Syria by the Sea (1873; Detroit Institute of Arts), El Khasné, Petra, and The Aegean Sea (1877; The Metropolitan Museum of Art). As the latter title suggests, the Church family’s itinerary through Asia Minor to Rome, along with the artist’s brief excursion to Athens in April 1869, exerted its influence, not least the Old World architecture that would inform his ideas for Olana. Yet even passing locales that did not figure in his major works, such as the Bavarian Alps that so thrilled Isabel when they paused at Berchtesgaden, Germany, in July 1868, prompted indelible images such as the ethereal apparition of a rainbow among granite peaks (Fig. 10).

The construction of his hilltop castle and the births of his last two children, Louis Palmer and Isabel Charlotte (in 1870 and 1871, respectively), required Church to spend more of his time upstate, though he did not neglect his brushes. Besides completing his major Near Eastern works, he executed a slew of oil sketches of the Hudson River Valley and Catskill region. Sunsets and twilights over the Catskills were essayed frequently, of course, but new to his repertory were winter prospects, many oriented to the south, down the Hudson, of which he produced more than twenty in two years. The most distinctive of them may be that seen in figure 11. Its vertical format accommodates not merely the frozen terrain but the brilliant nimbus clouds in a high, cold heaven that deepens to a sonorous blue. The whole is warmed by the pink imprimatura revealed in the clouds, the distant river, and the snow at the base of the picture. The dashing in of pasty white for the clouds, and their resulting vitality, looks forward to the impressionism of William Merritt Chase in the 1890s. The artist was certainly pleased with it, since he framed the sketch for display in the house.

The flush of sketching activity in the early 1870s coincided with the first symptoms of the rheumatoid arthritis that would increasingly plague Church. In the 1880s he virtually stopped executing large pictures, and to relieve his symptoms began spending nearly every winter in Mexico; his beloved Isabel, who contended with various ailments of her own, frequented more tropical locales in the southern U.S. Descriptions and photographs of the artist in those years make it difficult to see how he could paint at all, yet his will power and essential optimism seldom flagged. He continued to sketch in both pencil and oil, and occasionally completed cabinet-sized paintings of astonishing beauty and, given the circumstances, poignancy. Among the most unusual and memorable of those is Mexican Forest—A Composition (Fig. 12), painted in 1891. At first glance the picture’s subject, a deep wood interior glimpsed by sunlight, so uncharacteristic of the artist, seems like a concession to the contemporary taste for French Barbizon School painting and its American manifestation in the paintings of George Inness, who supplanted Church and his colleagues as the nation’s most admired landscape painter. Yet it also discloses the artist’s untiring phenomenological curiosity: the grand old bole on the right of the composition probably reflects his awareness of a prodigious cypress tree, fifty-two feet in diameter, which grew at Santa Maria del Tule. But Church also mentioned to a friend at this time that he wanted, while he could, to complete more paintings for his family, a sentiment that may lend mortal significance to his old monarch of the forest, and to the angelic white bird vacating the clearing beyond.

By the time of his death in 1900, Church was virtually forgotten, his representational aesthetic superseded by modernism; his idealism eclipsed by Darwinism. But the nationalism revived by two world wars created the climate in which the work of Church and the Hudson River School fraternity was gradually rediscovered. Louis and Sally Church preserved Olana long enough to see that revival, which helped ensure the rescue of the house and its remarkable contents. The current renovations are a measure of the diligence of New York State and The Olana Partnership. Both have worked to sustain the estate and its contents for future generations. As they do so, the public continues to benefit by treasures from Olana.

The Olana Partnership, Hudson, NY, and New York State’s Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, Albany, NY, organized Treasures from Olana: The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church. For information visit Olana.org.

—

Kevin Avery is associate curator in the Department of American Paintings and Sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and is guest curator of Treasures from Olana.

This article was originally published in the Late Summer 2005 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.