What is the Secret Behind the Enduring Popularity of Chinese Ink Painting?

|

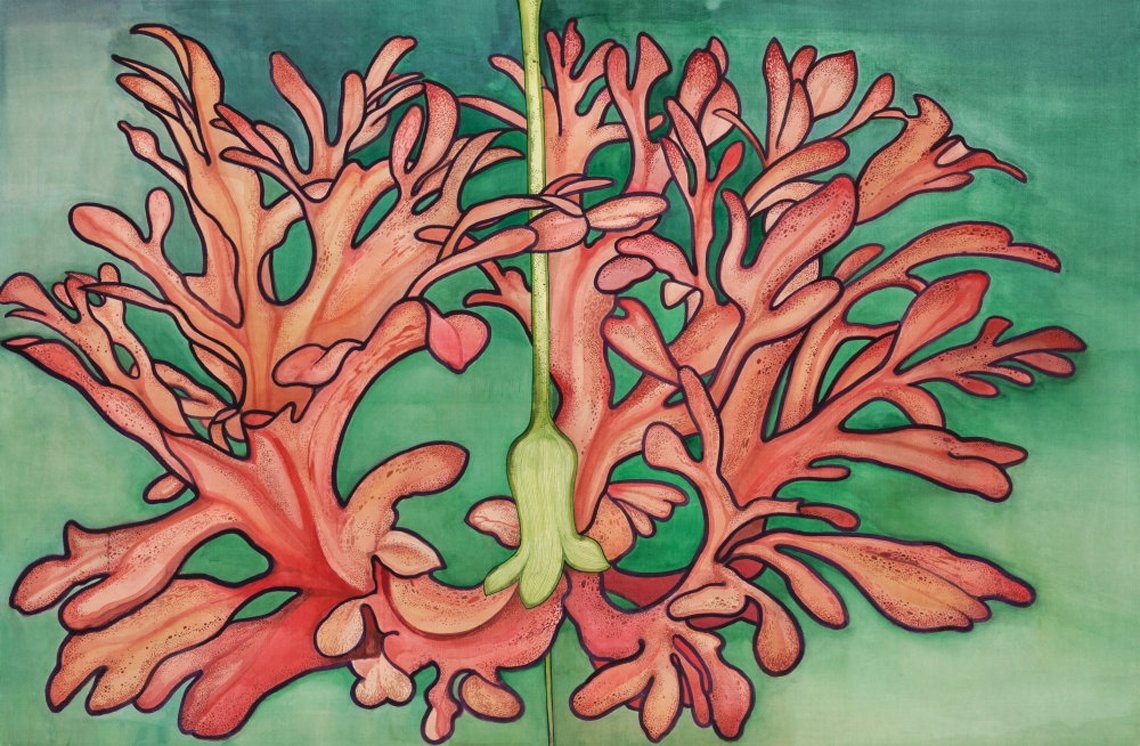

Chen Duxi, Paphiopedilum 兜兰, 2022. Mineral pigment on silk. Image courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York. |

What is the Secret Behind the Enduring Popularity of Chinese Ink Painting?

by Li Wen

Enter the home of a Chinese person, in China, or anywhere in the world, and there is a strong chance you will encounter ink painting of one kind or another — usually in the form of a poem or guiding aphorism about life, family and honor.

| |

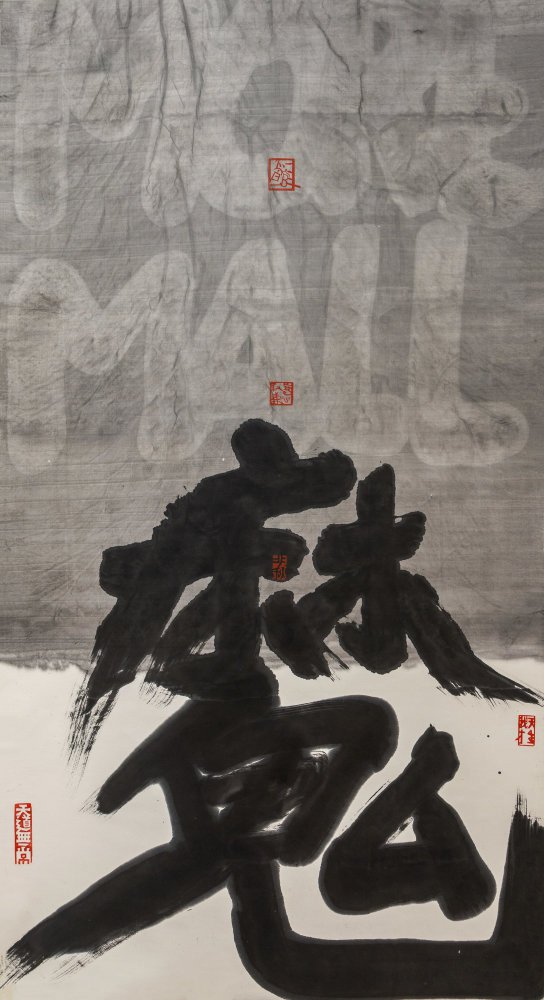

Fung Ming Chip, 时速音乐字 Music Script, 2013. Sealed ink on paper. Image courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York. |

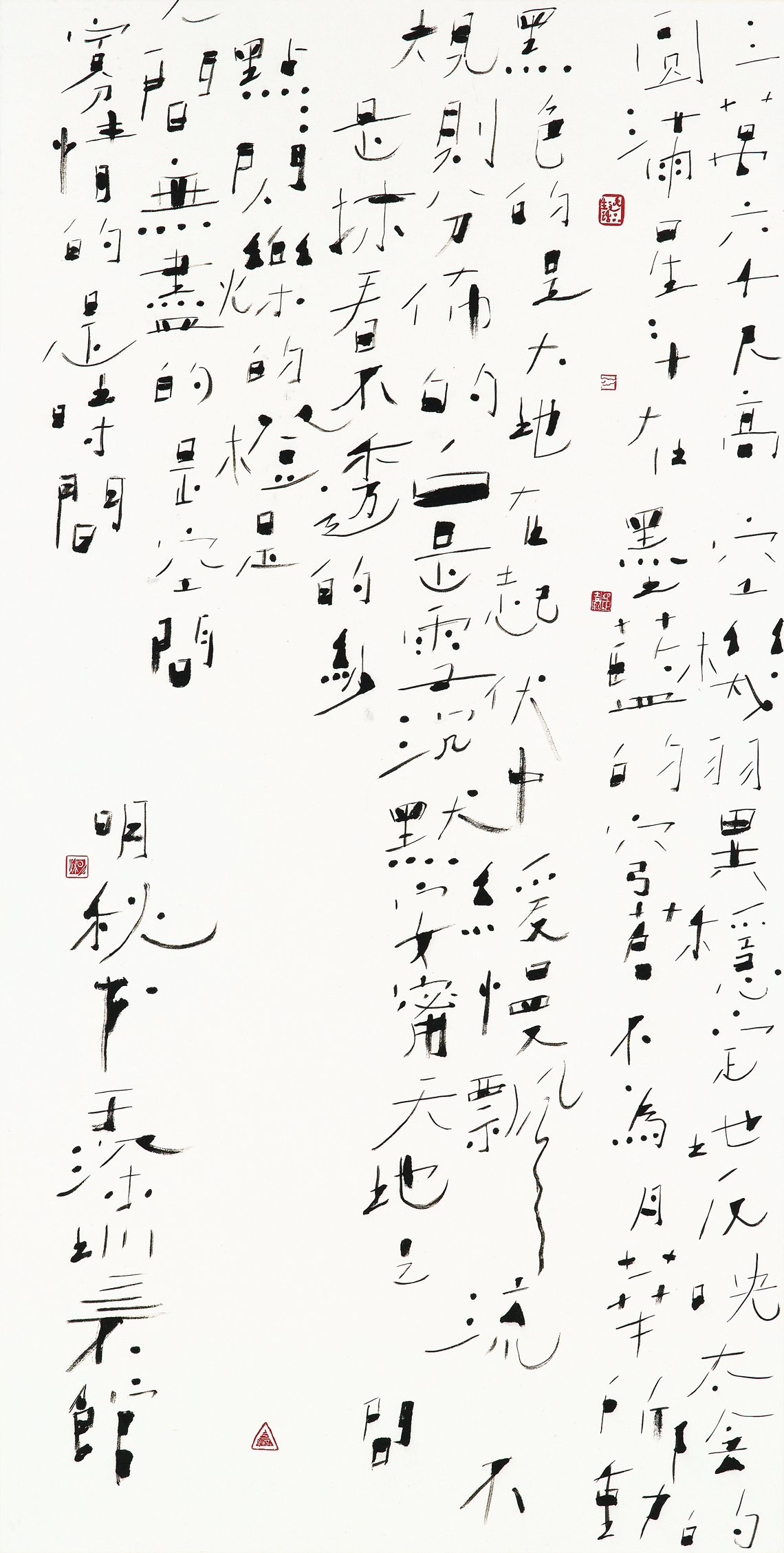

Calligraphy, with painting, poetry and music, constitutes one of the four major traditional arts of China. Calligraphy is viewed as the supreme art form of the four, given that poetry and ink painting are an extension of the art of calligraphy — all are done with a brush that is dipped in black ink and then applied to an absorbent paper.

Chinese script goes back five thousand years and first appears on tortoise shells and animal bones. Initially, it was used to record events. Over time, aesthetics and the meaning of the characters drew attention, and calligraphy began to emerge as an art form distinct from mere writing. How things were written now became as important as what they meant. The strength and speed of the brush strokes came to be admired as they were believed to reflect the inner energy and mind of the creator.

Calligraphy requires training to fully understand and appreciate. Each year, millions of Chinese children learn calligraphy at school and practice writing at home with a brush made of bamboo and animal hairs. Before dipping the brush into black ink, children are obliged to study the characters and memorize the strokes in order to be able to write them off the top of their heads. The brush cannot be soaked for too long in the bottle, otherwise, the ink will splatter on the paper before writing even begins. It takes patience, concentration and control as the ink doesn’t allow error or correction.

Each mark placed on the page has to be done in a single confident, definitive stroke. Students are advised to take a deep breath before a mark is made, the back straight, place the brush at an angle of 90 degrees from the table surface and concentrate attention on the tip of the brush. The practice sessions consist of writing one character over and over again for many hours. The more the student practices, the more fluid and expressive the calligraphic lines become, or that is the desired goal.

Calligraphy practice is often a communal activity, with other family members joining: first an ink stick is ground against a rough ink stone, a few spoons of water are added to form a liquid, paper is prepared, and practice begins. Results are shared, assessed, and discussed. Those who write beautifully are admired in a country where, six decades ago, only 20% of the population could read and write.

The purpose of traditional Chinese painting is to “write the meaning of things” (in Chinese 写意), which means, essentially, to express truth. A popular ambition for artists is to reflect “inner peace,” often viewed as the expression of the essence and beauty of life — something that in traditional Chinese paintings is most often found in the depiction of nature. Lotuses, for instance, are often viewed as symbols of purity, strength, and resilience because the flowers rise from muddy water without a stain.

|

| Chen Duxi, Lanterns 灯笼, 2022. Mineral pigment on silk. Image courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York. |

|

Wei Ligang, The Dews from the Tung Trees Floating in the Woods; Smoke Float Profoundly from the Furnace, 2018. Ink and acrylic on paper. Image courtesy of Michael Goedhuis. |

|

Yang Yanping, Autumn Love, 1998. Ink and colour on paper. Image courtesy of Michael Goedhuis. |

“The ultimate ‘beauty’ of a work does not depend on its beauty as we may see it by looking at it. It is the result of its inner ‘truth’ and it is this moral concept that is at the heart of all Chinese aesthetics,” said Michael Goedhuis, an art historian and London-based dealer who sought to bring Chinese contemporary ink art to Europe and the United States in the 1990s. He had a gallery in New York for several years as well.

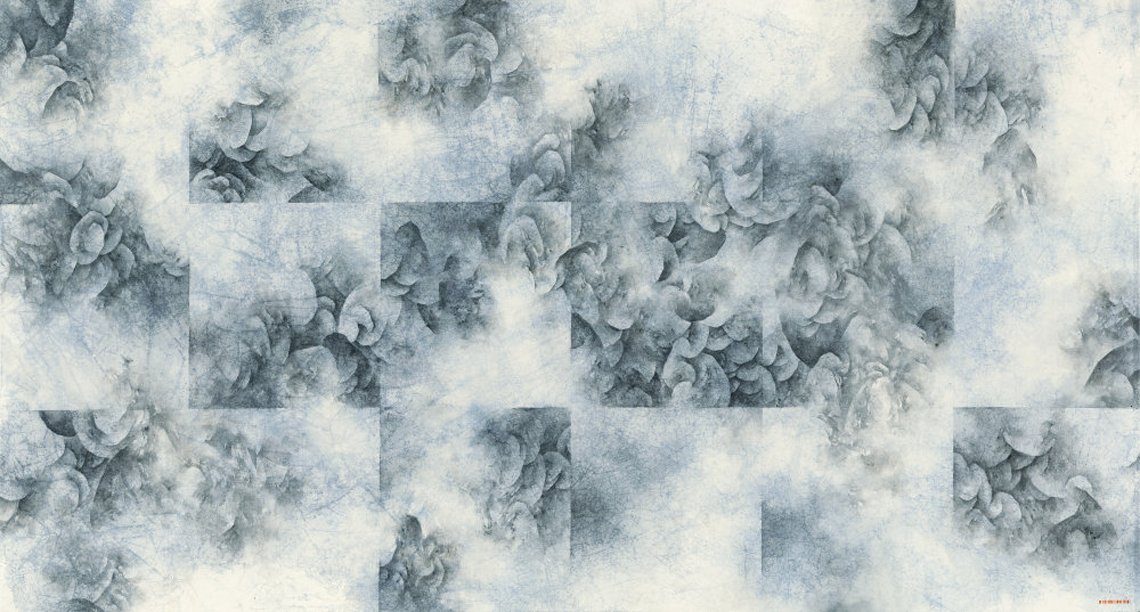

Calligraphy is not as popular today as it once was with contemporary Chinese artists. Since the early 20th century, the "ink art" tradition has increasingly been supplanted by introduced art forms, such as oil painting and sculpture as well as new media art practices. In response, in the early 1960s, the modern Chinese ink painting era was born as artists shifted away from traditional methods of ink painting to incorporate contemporary artistic techniques and new subjects for depiction.

Contemporary ink painters in China, specifically those who have sought to update ink painting techniques are divided into two categories, those who maintain a sense of tradition and traditional techniques such as Liu Dan, Li Xubai and Yang Yanping, and those who represent a more contemporary and avant-garde style of ink painting such as Xu Bing, Wenda Gu, Yang Jiechang, Qiu Anxiong or Qiu Zhijie. The second group are not strictly ink painters but artists who incorporate ink painting materials and techniques. They have received the most attention in the international art market, Goedhuis says. “Chinese painters who can break boundaries and break into new languages of expression are succeeding in the international art world,” he says.

|

Yau Wing Fung, Riding Mist X 驾雾 10, 2019. Ink and color on paper. Image courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York. |

Wei Ligang is another artist who has been at the forefront of contemporary Chinese avant-garde ink painting. He breaks with orthodox structures and colors by distorting the characters through brushstrokes to the point that they are not readable, a practice that other Chinese ink painters have simultaneously employed, using the forms of calligraphy as visual marks. His works were included in a pioneering show of Chinese ink painting organized by Gordon Barrass for the British Museum in 2002.

Over the years, while most of his paintings were bought by clients from Europe and the U.S., Goedhuis believes there is an enormous opportunity with a new generation of buyers from China and the Chinese diaspora. The Chinese are inclined to buy art from their own culture, or a contemporary interpretation of their traditional arts.

| |

Fung Ming Chip, Rubbing Script, 拓字, 2017. Ink on paper. Image courtesy of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, New York. |

Min Xiao, a Chinese artist and collector who lives in the United States, concurs with Goedhuis. “If I buy artwork from a Chinese artist, I’d like to see Chinese elements in a painting,” she said. “I want something current, but also speak to my Chinese roots.”

Elaine Hu, an architect from China who immigrated to California a decade ago, is a substantial collector of Chinese arts. Recently she bought and then renovated a century-old Victorian house in the San Francisco area. “I love contemporary design, especially with an Asian touch,” she said. “Tradition is the backbone of our society. In an evolving world, we want change, but we also want to mix the old and the new.”

In her home, located in the Pacific Heights area, Chinese decorative arts of all kinds are mingled throughout, together with modern furniture from Italy, America and France. On top of the marble fireplace is a work of Chinese calligraphy that in Chinese means "everything goes well" (如来). In the garden, a Buddhist sculpture with his palms closed and hands down in a gesture of supplication is positioned to greet guests.

Fu Qiuming, founder of Fu Qiumeng Fine Art, a New York-based gallery and advisory specializing in Asian art, said the market for contemporary Chinese ink art painting in America is undergoing an adjustment after the financial crisis in 2008. “The price of Chinese ink painting still requires a much larger sample size in order to form an established pricing system like other mainstream art categories such as post-war or contemporary art,” she said.

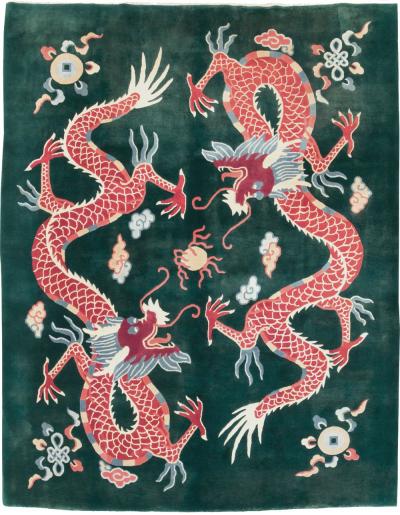

Yang Yanping 杨燕屏 is one of the most distinguished contemporary ink painters from China. Yang is well versed in many traditional painting styles but has excelled over the years in depicting the lotus flower, as a symbol of purity, transience, and fragility of nature and the potential for regeneration. Her works embrace modernism without jettisoning the traditional lessons of classical Chinese calligraphy.