From Houdon to Saint-Gaudens: A Private Collection of Nineteenth-Century Sculpture

- Fig. 2: View of the parlor, with the Houdon bust of Robert Fulton in the alcove. Childe Hassam’s (1859–1935) Spring Landscape, 1906, hangs above the carved mantel, in front of which is a Baltimore Classical drop-leaf table. On the left wall, above the New York side chair, hangs Venice by Rhoda Holmes Nicholls (1854–1930), below which is John Singer Sargent’s (1856–1925) Corfu of 1909. John Twachtman’s (1853-1902) Harbor Scene and Sargent’s Interior of the Basilica de San Marco, Venice, are highlighted over the Federal side chair to the right of the mantel.

It is rare for private collections of American paintings, drawings, and watercolors to span the entire nineteenth century—from America’s artistic development in the Federal period to the aesthetic movement of the late nineteenth century. It’s rarer still when the collection is coupled with American sculpture spanning the same period, particularly considering that there were few American sculptors of note for much of the first half of the century. The art within this East Coast private collection encompass paintings by Trumbull and Stuart to Chase and Sargent and sculpture from Houdon to Saint-Gaudens.

Most American sculpture of the early nineteenth century consists of portraits that celebrate the founding fathers of the nation. As such they complement paintings of the period which, while also recording the likenesses of the early patriots, include historical events, often battles. By mid-century, American paintings focused on recording the expanding boundaries of the nation in landscapes, often in conjunction with the discovery of topographical wonders as the country grew west across the continent. At the same time, American sculpture entered into what is described of as the neo-classical phase with images of mythological gods and goddesses, mainly relevant if one knew the stories behind them; most owners of the time likely did. Sculpture was meant to not only enliven the space of larger and more elaborate homes of the growing class of prominent businessmen, but to display a cultivated knowledge of classics. Toward the end of the century, subject matter of American art expanded into a new vision of landscape painting—American Impressionism being a prime example—and a more personalized record of likeness in portrait painting, which became more natural and accessible—avoiding artifice and obvious posing. At the same time sculpture became less formulized—to the point where some examples were also described (sometimes derisibly) as impressionistic.

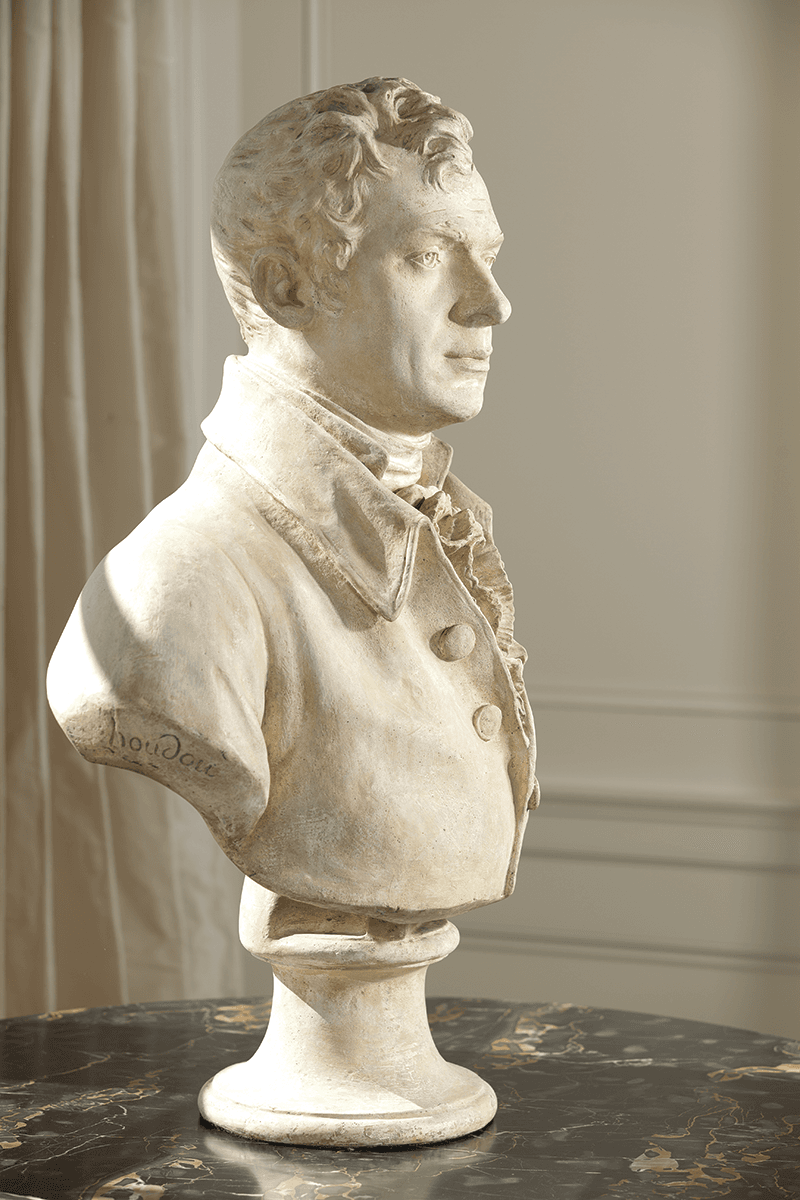

In the heady first years of the New Republic, such seismic events as the election of George Washington as the first U.S. president in 1789 needed to be celebrated by public statuary and portrait busts—as was traditionally done abroad. There were only a few artists of note able to accomplish such a commission, all of whom were European. The Assembly of the State of Virginia voted to commission a full length marble statue of Washington and contacted Thomas Jefferson, then living in Paris, to nominate a suitable sculptor. Jefferson suggested French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828), whom he described as “being unrivaled in Europe.” In 1803/4, Houdon completed what is considered to be one of his finest portrait busts—that of the 38-year-old Robert Fulton (1765–1815), an American inventor and entrepreneur. In 1797, Fulton, then living in London, moved to Paris to promote the building of a steamship of his design to travel the Seine in 1803. What better way to commemorate these events than to commission a portrait bust by the foremost sculptor of his day? The plaster bust of Fulton that now sits in an alcove of the parlor in the collector’s home was first exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1804 (Figs. 1, 2).

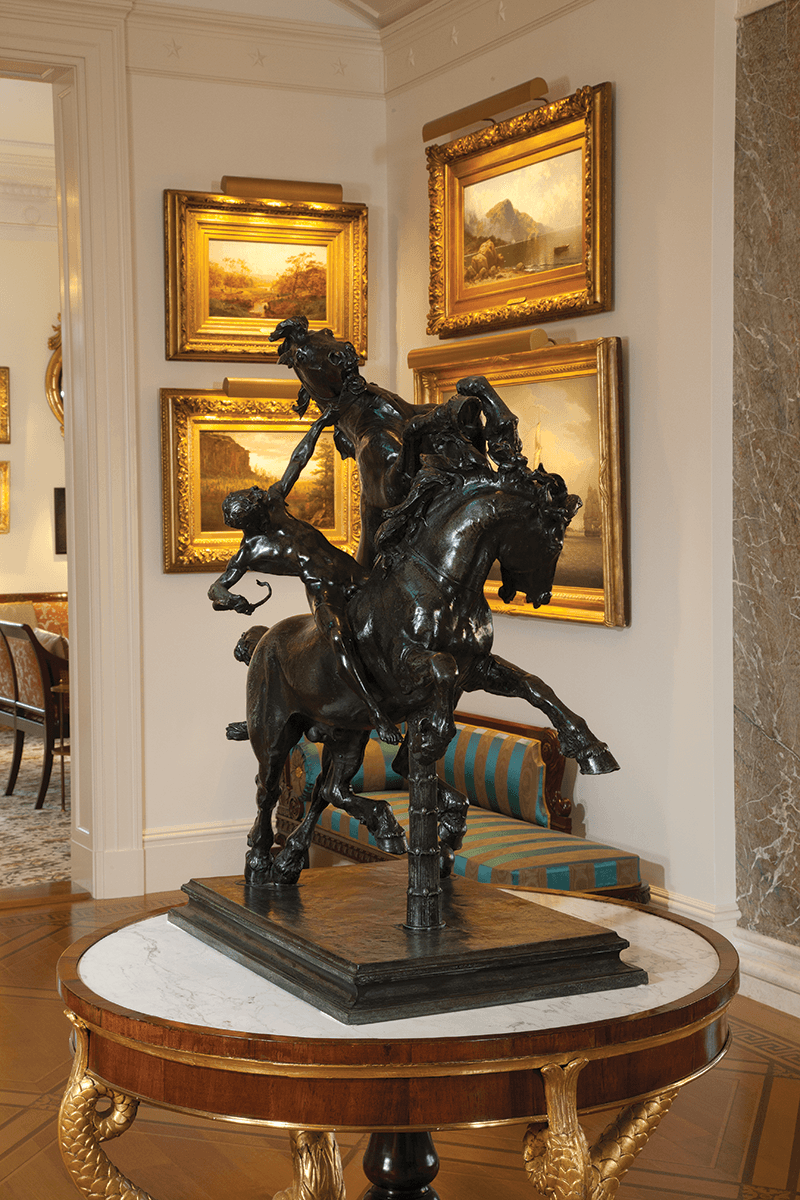

Past the entrance foyer of the home is the first floor gallery, with its centerpiece, The Horse Trainer by Frederick MacMonnies (1863–1937) (Figs. 3, 4). In the 1890s, Stanford White was asked to redesign the Park Circle entrance to Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. He chose MacMonnies to create the sculpture for the plan, consisting of monumental works on two large plinths, one on each side of the entrance road. The sculptor’s two related images were meant to be an allegory of “the triumph of mind over brute force.” The work was completed in plaster in MacMonnies’ Paris studio using Andalusian draft horses he purchased as models for the rearing horses ridden by a young tamer. The work in the collection is a reduced size “pin model” for the sculpture on the south side of the entrance. (A “pin” model refers to pins holding various sections of the work together, so labeled to allow various parts of the bronze to be taken apart and cast and then reassembled.) The “pin model” of any work is not only unique, but is closest to the original intent of a sculptor and especially noted for the sharpness of detail and crisp line.

At the base of the staircase leading to the second floor stands Atalanta, carved in 1874 by William Henry Rinehart (1825–1874) (Figs. 5, 6). Atalanta is shown running in a footrace she devised to discourage suitors—if she won, the suitor would die. She foiled all her suitors until Hippomenes tricked her by throwing three golden apples in her path. When Atalanta stopped to pick up one of the apples, Hippomenes won the race and her hand in marriage. This work, executed in Rome, stands on its original pedestal and descended in the family of the original buyer, John H. Warren of Troy, New York, later to be given to the Troy Public Library before entering the current collection.

In a niche along the staircase leading to the second floor is a marble bust by Chauncey Bradley Ives of the mythical figure Ariadne (Fig. 7), first modeled by Ives in 1852. Left on the Isle on Naxos by her lover, Theseus, she was rescued by Dionysos whom she then married, only to be later killed by Perseus. Hiram Powers’ marble carving of Psyche, is placed in the niche to the left of the stairwell window. Conceived in 1848, Psyche was the maiden who fell in love with Cupid, and was later made immortal by Cupid’s mother, Aphrodite. Both of the busts are representative of the mid-nineteenth century vogue for neo-classical sculpture.

At the end of the staircase railing in the second floor gallery is a bronze statue of Nathan Hale (Fig. 8), a reduction of the work MacMonnies first exhibited in plaster at the Paris Salon of 1891, where it, along with another work in plaster, won a second-class gold medal, the highest award available to “foreigners” by the somewhat xenophobic French judges, and the first won by an American sculptor. This very important “win” for MacMonnies led to other sculpture commissions. The idealistic rendition (no known likeness of Hale exists) of the twenty-one-year-old American Revolution hero, who declared as he was led out to be hung by the British on September 22, 1776, accused of spying, “I only regret I have but one life to give to my country,” epitomized the patriotic fervor of the newly established country. The completed full figure sculpture was commissioned for and still stands in New York’s City Hall Park.

The library, just off the first floor gallery, features a rare pair of marble sculptures by Hiram Powers (1805–1873), one of the first classically trained American sculptors. Conceived and sold as a pair in the mid-nineteenth century, this set is the only known pair that remained intact, descending in the family of the original purchaser, Sir Charles Scrace Dickens of Coolhurst, West Sussex, England. The Bust of the Greek Slave (Fig. 9) is among Powers’ most famous works. The full-length, nearly life-sized marble was meant to portray a young woman, stripped bare by heathens and manacled and revered for having retained her Christian virtue; Powers’ bust presented a more demure image. The companion work, the Bust of Proserpine (Fig. 10), is of the Roman goddess, daughter of Zeus and Demeter, and wife of Pluto, god of the netherworld. Though the tale of Proserpine involves abduction and rape, Powers depicts her in a rather virtuous state; fitting as a companion to the Greek slave.

In the same room is Emma Stebbins’s The Lotus Eater (Fig. 11). Stebbins (1815–1882) was one of the oldest of a group of American women sculptors, dubbed the White Mormalleon Flock, who moved to Rome to work during the second half of the nineteenth century. In addition to the cultural inspiration, Italy was home to some of the best marble quarries in the world, source of both Carrara and Seravegga white marble. The Lotus Eater was Stebbins’ earliest marble sculpture; it was both a commercial and critical success. The title refers to the mythological story of Lotus Island, where travelers who ate the lotus fruit, fell into a peaceful state and remained on the island forever. So popular was the work that Stebbins later made a bust version of the wistful youth, wearing a wreath of flowers in his hair, as seen here. This too became popular, and Stebbins produced a limited number of copies—limited because she never allowed studio assistants to work on her commissions and did all the work herself.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) was one of the leaders of the American Renaissance movement of the late nineteenth century. Translating French artistic sensibility into a muscled and elegant American point of view, his work memorialized in bronze historical and contemporary figures on the American scene. He also created portraits of his many friends, the artists and writers who played a vital role in the American arts of his day.

On the north wall of the parlor hangs Saint-Gaudens’ intimate bronze portrait of the Gilder family: Helena De Kay Gilder, her husband, Richard Watson Gilder, and their son, Rodman De Kay Gilder (Fig. 12). Richard Watson Gilder was a poet and editor of Scribner’s Monthly magazine and its successor, The Century Magazine. His wife, Helena, was one of the founders of The Society of American Artists. Together they were an indomitable force on the American art scene of their time; it is fitting that it hangs in a room with paintings by many of their friends. This bronze descended from the descendants of their daughters.

In a corner of the terrace that surrounds three sides of the house is the Four Seasons Sundial of 1902, by Enid Yandell (1870–1934) (Fig. 13). A tour de force, four intertwined figures representing the four seasons hold up the sundial, with a bird wing as the gnomon, which casts a shadow on the time of day plate, exactly positioned by the longitude and latitude of its location. Born in Kentucky, Yandell was only twenty-three years old when she was hired to create caryatids for the Women’s Pavilion at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. For this, she worked under the Chicago sculptor, Lorado Taft—becoming one of his “white rabbits” who completed various sculpture projects for the fair. Four years later she was in Paris at work on Pallas Athena, one of her monumental sculptural pieces commissioned for the Tennessee Centennial Exposition in Nashville.

On the opposite corner of the terrace is the Girl with Fish fountain of 1914 by Edward Berge (1876–1924) (Fig. 14). Berge studied at the Académie Julian in Paris for three years and also with Auguste Rodin. He became well known for his fountains, which usually included the playful image of a young figure, in this case, a young girl pouring water from a jug-shaped bottle into a pool that includes the heads of two fish spouting water. The fountain not only enhances the space, but the gentle sound of the running water adds to the serenity of the location.

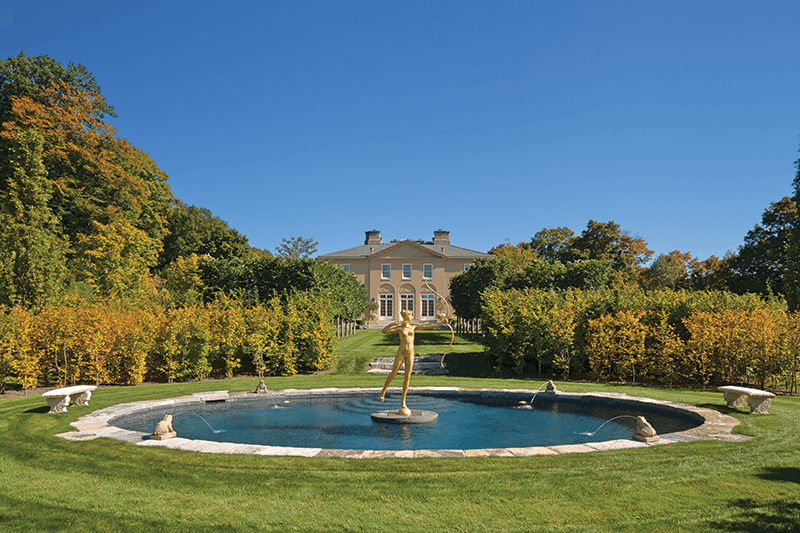

At the end of a long grass alley extending from the house is Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Diana (Fig. 15). The Roman goddess of the hunt is centered in a round reflecting pool. The famous image was originally created in 1891 as the weathervane for the tower of a new Madison Square Garden building designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White on the corner of Madison Avenue and East twenty-sixth Street, New York. The first version was eighteen feet high and weighed 1,800 pounds. Too heavy for a weathervane and deemed disproportionately large for the tower, it was replaced two years later by a thirteen-foot version. A few six-and-one-half-foot versions (including the cast in this collection) were later cast from a mold taken from a cement model given by Saint-Gaudens to Stanford White in 1894.

D. Frederick Baker is a regular contributor to Antiques and Fine Art. He oversaw the completion and posthumous publication of Ronald G. Pisano’s catalogue raisonné of William Merritt Chase.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.