Did You Know? Mapping America’s Road to Independence

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

We all use maps to find our way from one point to another. Maps also relay stories and information important to historians. In the exhibition We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence, maps provide guidance to the paths this country took to evolve into a society. Using geographic and cartographic perspectives, We Are One traces the American timeline from the French and Indian War to the creation of a new national government. The exhibition includes related objects that illustrate the many ways in which the story of the Revolution can be told.

In addition to being documents, maps and historic material hold information we may not recognize or know today. The following collections offer interesting insight into the American story.

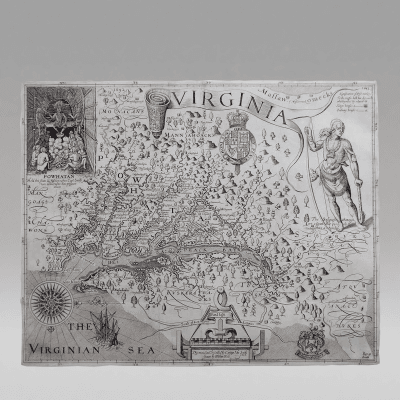

By 1750, the commissioners of the Board of Trade recognized the need for a comprehensive map that illustrated all of Britain’s American holdings and counteracted French claims. John Mitchell was given access to all of the maps, charts, journals, and reports belonging to the Board of Trade as well as the records of the British Admiralty. Attempting to prevail over French claims, Mitchell meticulously researched the original charters of each of the colonies and included his findings on the map. His work was immediately recognized for political the assertions it made on Britain’s behalf and helped to galvanize public sentiment in favor of defending British holdings during the French and Indian War. Following the Revolutionary War, treaty negotiators used Mitchell’s map to establish the boundaries of the new United States.

Did you know?

Glass could not be manufactured in pieces large enough to span the surface of a map that was larger than a single sheet of folio paper (about 24" by 19"). Therefore, large wall maps were often pasted to linen and attached to rollers so that they were both lightweight and easily portable. Large-format maps were also bound in atlas form or pasted to linen and folded to fit into a case.

Although the subject has not been identified, this miniature portrait, painted around 1776, appears to be the earliest known depiction of an officer in America’s Continental Navy. It is attributed to Joseph Dunkerley, one of the most important miniaturists of the Revolutionary War era. Born in England, Dunkerley came to Boston with British forces about 1775, but deserted to serve in America’s Continental Army. He left military service in May 1778, but continued to paint miniatures for another decade.

Did you know?

The Continental Navy was established in 1775 with a fleet of seven ships. By the following year, the Continental Navy had twenty-seven ships against Britain’s 270 ships.

George Washington read the Declaration of Independence to his troops in New York City on July 9, 1776. Afterward, New Yorkers joined with enslaved or freed Africans to pull down a statue of King George III. People gathered at their windows and on balconies to view the spectacle. The destruction of the statue by the people represented America’s challenge to monarchical tyranny.

Did you know?

The lead from the dismantled statue of George III was melted down and made into musket balls that were used by American soldiers in their fight against the British.

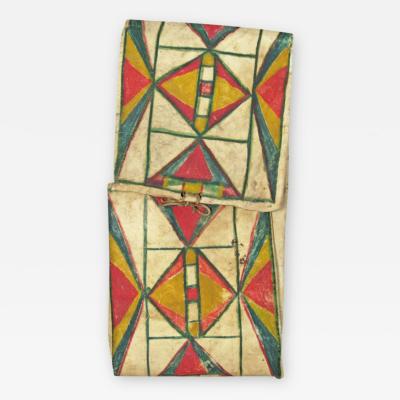

Prior to the 1740s, only a small number of rifles appear to have been owned by Native Americans. This changed during the French and Indian War when many more were distributed to the Native population. These rifles were of American or European manufacture. It wasn’t until the Revolutionary War that the British began making such firearms specifically for the Indian trade. This example, by William Wilson & Co., is one of two grades of Indian rifles offered by the firm during the war, and cost either £2. 12. 6 or £2. 10. 0.

Did you know?

This London-made rifle closely follows an eastern Pennsylvania-style rifle, representing a rare reversal for the English trade. It is one of the first examples of a distinctly American item being directly copied in Britain to satisfy demand.

When General George Washington realized that Cornwallis was planning to launch a campaign in Virginia, he dispatched the Marquis de Lafayette and twelve hundred light infantry to the colony. Lafayette was accompanied by a group of aides that he brought with him to America. One of them, a French topographical engineer named Michael Capitaine, made detailed plans of all of Lafayette’s campaigns.

Lafayette was well aware that his army was no match for Cornwallis, so he devised a strategy to engage the British general in a series of skirmishes rather than by direct confrontation. This map carefully detailed Lafayette’s strategy. Drawn by Capitaine, it is almost certain that this is the map that he and Lafayette consulted each day to mark their positions in relation to those of Cornwallis.

Did you know?

This map was made by using an early form of tracing paper. Traces of walnut oil discovered during conservation suggest that the small sheets of writing paper pasted together to form a large sheet were coated with oil to make the paper more translucent, enabling the engineer to place it over existing printed maps in order to record the geography.

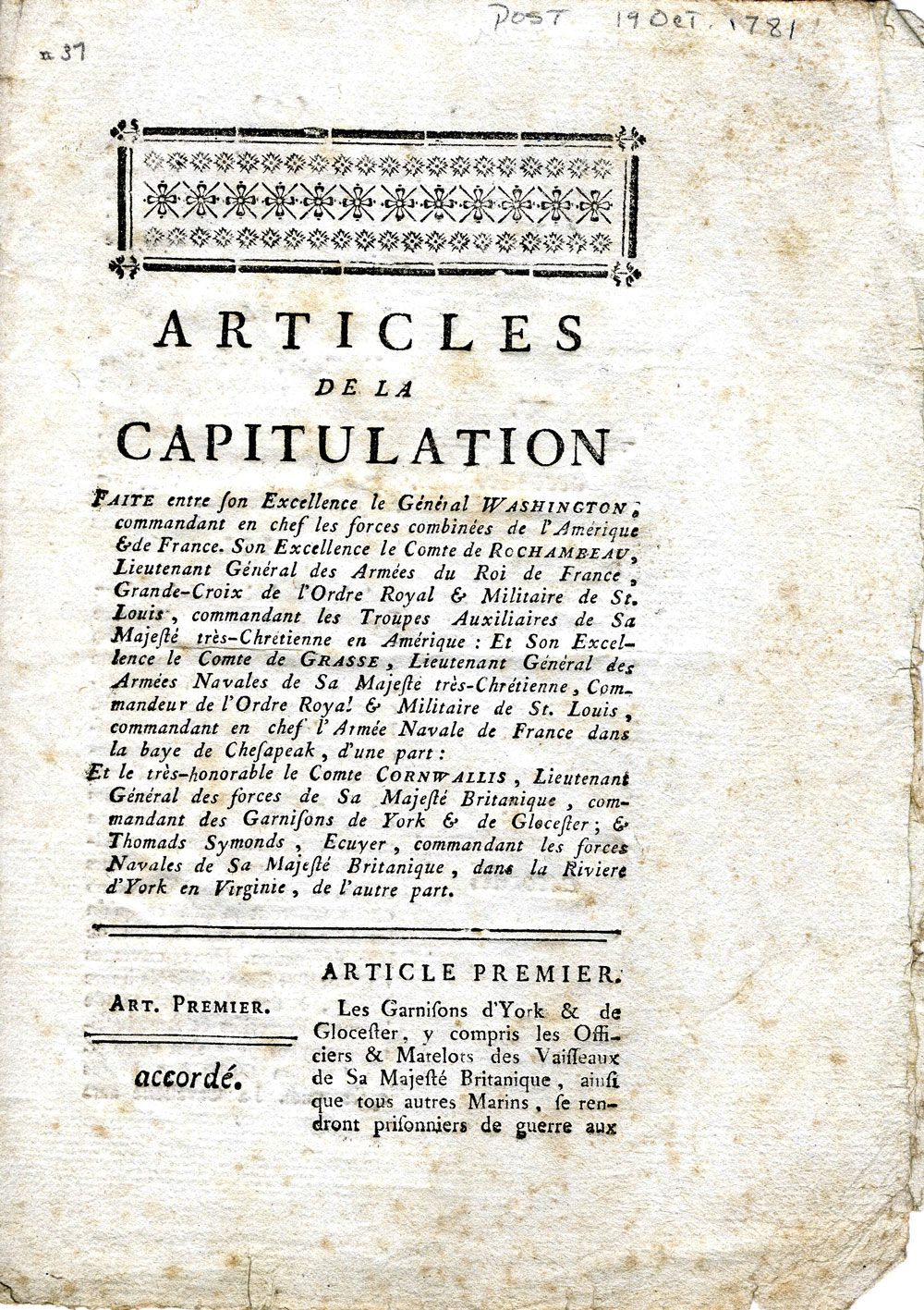

The fourteen articles of surrender agreed to at Yorktown by Cornwallis determined such things as where the troops, now prisoners of war, were to be sent, how to care for the sick and wounded, and details outlining the surrender ceremony. It is thought this pamphlet was printed on the press of the Ville de Paris, de Grasse’s flagship, then in Virginia waters.

Did you know?

It was fairly common for armed ships to carry printing presses to aid with communication. During the Revolution, the British engaged in economic warfare by printing counterfeit American currency while anchored in New York Harbor.

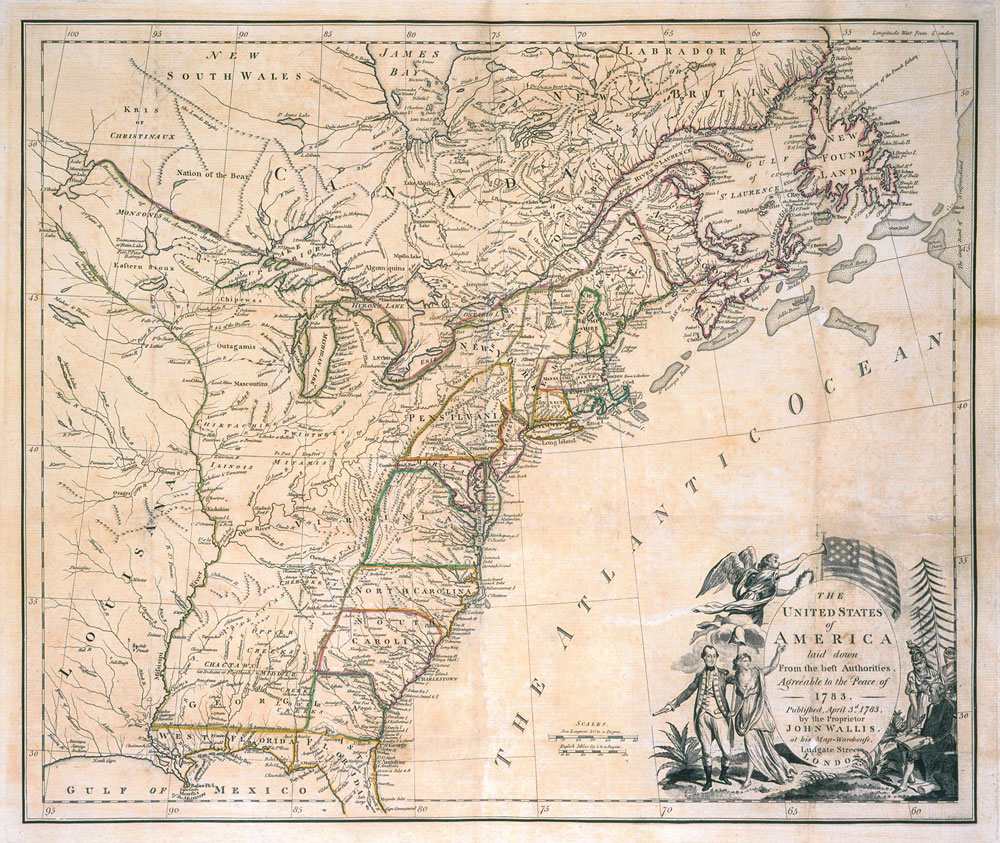

The preliminary articles of peace drafted by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Henry Laurens were signed at Versailles on January 20, 1783. Cartographers immediately rushed to issue maps that defined the boundaries of the independent nation. This map delineated state boundaries, Native American lands, and the remaining French and Spanish holdings.

The decorative cartouche, which symbolizes peace in America, is particularly noteworthy. The allegorical scene portrays George Washington alongside Liberty, and Benjamin Franklin, supported by Justice and Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and war, writing the Treaty of Paris. This is the first British map that illustrated the American flag.

Did you know?

The Flag Act directed “That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation…” Although adopted as the national banner in 1777, it was not widely recognized by Americans until 1789, when George Washington was elected President.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, among others, believed that the success of the new nation was tied to the exploration and cultivation of the frontier. Following the Purchase of Louisiana in 1803, Jefferson commissioned Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to map the newly acquired territory and to find a route across the continent. Their expedition opened the door for new explorations and helped to establish a United States presence in the West. Henry Tanner incorporated information from discoveries made by Lewis and Clark (1804–06), Zebulon Pike (1806) and Stephen H. Long (1819–20) to create the most significant map of the American West produced during the first decades of the nineteenth century.

Americans began to regard natural wonders as symbols of their national pride. The cartouche on Tanner’s map combined images of both Niagara Falls and Natural Bridge along with other symbolic forms of American fauna such as a rattlesnake, a beaver, and an eagle.

Did you know?

Thomas Jefferson purchased Natural Bridge and the surrounding 157 acres in 1774. He described it as “”the most sublime of Nature’s works.” In 1809 he wrote, “I view it in some degree as a public trust, and would on no consideration permit the bridge to be injured, defaced, or masked from public view.” In 1998, it was designated a National Historic Landmark.

We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence displays approximately 90 maps and objects and is on view at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, through January 29, 2017. It marks the first collaboration between the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg and the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. For information, visit www.history.org.

-----

Margaret Pritchard is the deputy chief curator and curator of prints and maps at Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.