Cornelius & Baker: Manufacturers of Lamps, Chandeliers, Gas Fixtures, Bronze Ornaments

In January 1, 1852, the Philadelphia newspaper North American and United States Gazette announced that “Robert Cornelius & Isaac F. Baker, have this day associated with . . . William C. Baker, in the manufacture and sale of Lamps, Gas Fixtures &c. The business hereafter will be conducted under the firm of CORNELIUS, BAKER & CO.” Though the name was new, the firm was not. Its roots extended back to 1810, when its founder Christian Cornelius (Robert’s father) first listed himself in the city directories as a silversmith at 8 Pewter-platter Alley.1 Christian Cornelius apparently determined, however, that greater opportunity lay in the manufacture of lighting rather than as a silversmith, which proved to be a fortuitous decision. By the 1830s, he was garnering accolades for his lighting devices, and by the 1850s, his firm had become the largest of its type in the United States.

- Fig. 1: Mammoth gaselier with twenty-four burners made by Cornelius & Baker for the Vermont State House in 1859. It hangs in the Representatives Chamber, and measures twenty feet high by nine feet in diameter; bronzed and gilt brass, bronzed zinc, iron. Cornelius & Baker also supplied about two dozen wall sconces for the Vermont State House at the same time, most of which survive, unlike many fixtures the firm made for the State Houses of other states. Courtesy the Vermont State Curator’s Office.

This was no small accomplishment, for the country was rife with manufacturers, vendors, and importers of lighting devices, working to supply significant and growing demand. Virtually every city and town counted lighting manufacturers and vendors among its merchant class. Philadelphia was no exception. Samuel F. Bradford, Frederick Hancock, and Lewis Veron, all lamp vendors, and Edward Clark, Jacob Keim, John Ledbeater, Charles Carr, Ellis Archer, and Charles C. Oat, all lamp manufacturers, were among many in the city competing for the same market as Cornelius.2

In spite of vigorous competition, the Cornelius firm dominated the field for decades, only waning after Thomas A. Edison patented his incandescent light bulb in 1880. During the firm’s heyday, it produced some of the most elegant candle, oil, gas, kerosene, and electrical fixtures made in the United States. Fortunately, many Cornelius fixtures survive, providing insight into the stylistic and technical nature of its production, and by extension, deepening appreciation for the appearance of American interiors, both private and public, during the era (Figs. 1, 2).

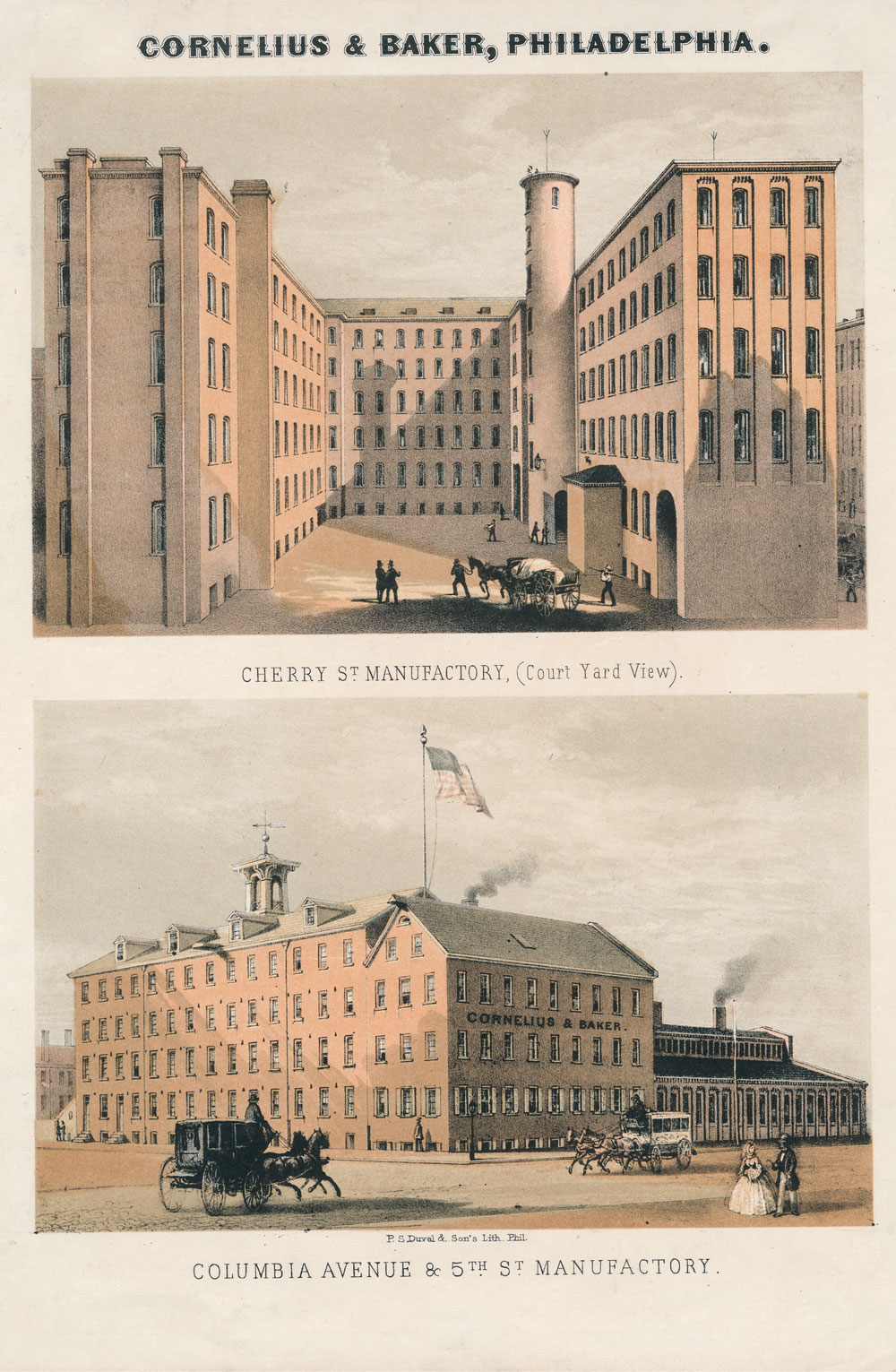

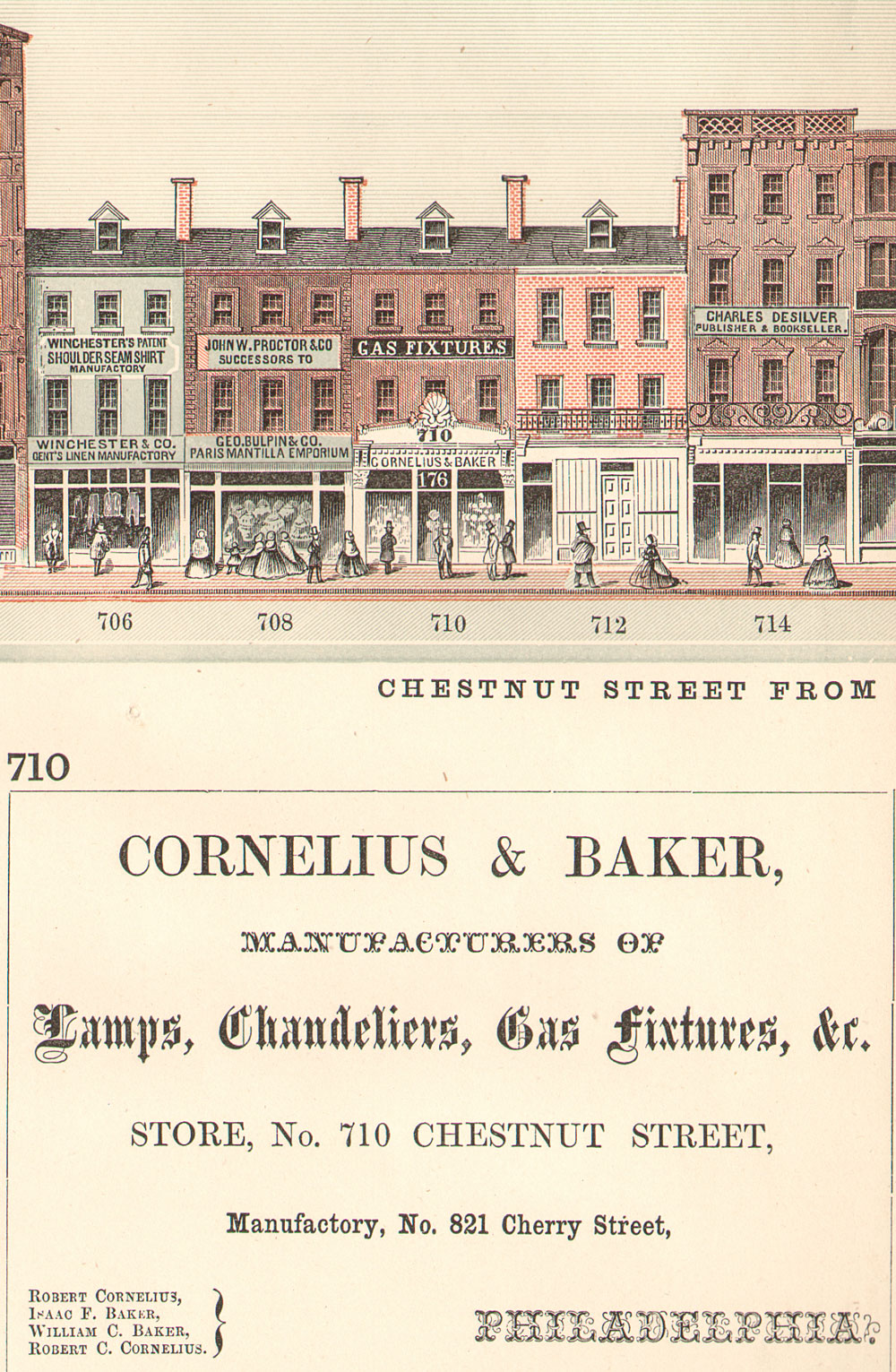

A number of social commentators wrote about the firm, the scale and scope of its production and the impact it had on mid-nineteenth century American’s sensibilities. A twenty-four page pamphlet published about 1858, Description of the Establishment of Cornelius & Baker, Manufacturers of Lamps, Chandeliers & Gas Fixtures, Philadelphia, is among the most informative.3 It states that the firm began as a small craft shop about fifty years earlier (in 1810), with the founder and two or three journeymen. Such was the demand for lighting in general and Cornelius’ fixtures specifically, that by the time the article was written the business had grown to encompass a six-story brick manufactory on Cherry Street, a five-story manufactory on Columbia Avenue, each almost a city block in size, and a separate three-story show and wareroom on Chestnut Street (Figs. 3, 4). It employed over five hundred and fifty men, women, and children, with two large steam engines supplying the motive power. The many work and display areas devoted to modeling, casting, spinning, stamping, dipping (in acids to clean), burnishing, fitting (parts together), painting and lacquering, glass cutting and finally, packing, are described in the pamphlet. In the last of these, packages and crates containing the firm’s products were addressed to every state in the Union, as well as to “China, India, various ports in South America, Havana, and the Canadas.” In the firm’s “museum,” a vast array of patterns and models were kept for use as inspiration by resident artists and designers.

- Fig. 2: Detail of the gaselier in fig. 1, showing the thirteen-inch high bronzed zinc statuettes standing between the two tiers of arms. Four of the figures are reductions of Hiram Powers’ celebrated marble statue of the Greek Slave. They alternate with allegorical figures representing Commerce, Science, Prudence and Eloquence. Courtesy of the Vermont State Curator’s Office.

Another record about the firm was generated by the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts, commonly known as the Franklin Institute. Founded in Philadelphia in 1824,4 an important component of the institute’s initiative consisted of annual competitive exhibitions to foster excellence in American arts and manufactures. The Cornelius firm displayed its wares in those exhibitions, beginning in 1830, and always garnered acclaim. Following the 1853 exhibition, the judging committee described the work submitted by the company as of such “great beauty, excellence, and taste [that] they bid fair to be soon classed in the department of Fine Arts.” 5

The admiration for the firm’s wares was not limited to the United States. In 1851, Cornelius & Baker submitted two massive chandeliers, each measuring fifteen and a half feet high by six feet in diameter, along with twenty-four “damask” solar lamps and seven “olive” colored solar lamps, to the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. Among the many admiring reviews, all were impressed with Cornelius & Baker’s submission, noting in their various publications that the chandeliers were “graceful specimens of workmanship, designed in good taste...the casting was remarkable for its fineness, sharpness, and uniformity” (Fig. 5). One noted that American lighting manufacturers “have attained so much excellence as to be willing to vie in the Exhibition with the oldest and most celebrated houses in the world.” 6

In spite of the subsequent revolution in lighting technology and changing taste during the twentieth century, admiration for lighting fixtures produced by the Cornelius firm never lost its luster. Cornelius candle, oil, gas and kerosene fixtures continue to be esteemed today by collectors, students, and enthusiasts of early Americana.

Little known today is the fact that Cornelius & Baker also produced parlor sculpture, During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, wealthy American householders, the increasingly vested middle class, and even those of more modest means increasingly sought statuary of American heroes (George Washington), ancient gods (Mercury), allegorical figures (Liberty), fictional characters (Walter Scott’s “Old Mortality”), and others, as evidence of their erudition and sense of style (Fig. 6). A lively trade in plaster, parian, terra-cotta, marble, bronze, and bronzed zinc statuettes ensued, most imported from Europe through merchants like Tiffany and Company in New York City and Alonzo & Francis Viti of Philadelphia.

Cornelius & Baker saw opportunity and entered this realm of production. Though not the only American firm to do so, it proved to be the most successful, due in large part to the business acumen of its founding partners who aggressively explored new marketing opportunities. The firm’s success was also due to the talented designers, modelers, and sculptors who worked under Charles Page (1819–1900), chief designer and head of the company’s design department from 1844 to 1864.

In contrast to imported European bronze statuettes, which were cast using the lost wax process, Cornelius & Baker cast theirs of zinc in brass molds (Figs. 7-8). Zinc was easy and relatively inexpensive to cast, and was typically patinated to imitate more expensive bronze and/or gold.7 The resulting figures compared favorably with imported bronze counterparts and cost considerably less.

The firm’s earliest statuettes, starting in about 1850, appear to have served as adjuncts for lighting. These consisted of small to medium sized figures measuring between four and eighteen inches in height. The subjects were sculpted for aesthetic and nationalistic sensibilities, as with the allegorical figures of Commerce, Science, Prudence, and Eloquence standing amid the arms of the great gaselier made for the Vermont State House in Montpelier (see figures 1, 2), and complemented by the figures of George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, William Penn, and the Revolutionary War Minuteman adorning accompanying wall sconces.

By the mid-1850s the company was casting increasingly large sculptures measuring from eighteen to over forty inches in height. These were for the most part intended as stand-alone sculptures for display on mantels, table tops, and pedestals (Figs. 9, 10). Whereas most of the firm’s statuettes were probably designed in house under the direction of Charles Page, others were copied with slight changes from imported European bronzes, while a few were adapted from the works of American sculptors, including Hiram Powers (1805–1873), William H. Rinehart (1825–1874) and Clark Mills (1810–1883) (Fig. 11).

- Fig. 11: Andrew Jackson on Horseback, by Cornelius & Baker, Philadelphia, 1855–1860. Bronzed zinc. H. 24 in. The original statue of heroic size was designed and cast in bronze by Clark Mills (1810–1883) and placed in Lafayette Park, in front of the White House in Washington, D.C., in 1853. In 1855, Mills patented the design and contracted with Cornelius & Baker to cast reductions in bronzed zinc for sale to the public. Private collection.

Allegorical and historical figures comprised important subject matter for Cornelius and Baker’s parlor sculpture. These statuettes were designed to satisfy style-conscious householders wishes to display their appreciation of art, literature and history, but also to exhibit their refined taste. By the early 1860s, Cornelius & Baker had added genre figures (puppeteer, hurdy-gurdy player, Civil War soldier, the biblical figures of Rebekah and Eliezer) to appeal to a growing taste for art that depicted everyday subject matter, perhaps best exemplified in the United States by the pottery genre groups of John Rodgers (Fig. 12).

Just as the firm’s lighting met with enthusiastic approval by discriminating critics, so too did its sculpture, as noted in the report of the twenty-fifth exhibition of American manufactures published by the Franklin Institute in 1856. Cornelius and Baker submitted ten statues in addition to many lighting devices for consideration by the exhibition committee. In response, the judges observed that “In color and evenness of the tint, the bronzes and verd antiques bear comparison with the best French” 8 (Fig. 13).

The September 17, 1869, issue of the Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin carried the following notice: “The copartnership heretofore existing under the firm and name of CORNELIUS & BAKER was dissolved by mutual consent on July 2, 1869.” Following dissolution, the former partners created two separate companies, Cornelius & Sons and Arnold & Baker, both of which continued to manufacture and sell lighting and associated fixtures. Even though the firm operated under the imprimatur “Cornelius & Baker” for only eighteen years, it represents a high water mark in the history of American lighting and parlor sculpture. While the firm’s lighting has always enjoyed a celebrated status, its parlor sculpture is only now beginning to be recognized as a significant contribution to the arts of mid-nineteenth century America.

-----

Donald Fennimore is curator emeritus, Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. He is currently researching, with Frank L. Hohmann III, the tall clocks of William Claggett.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. R. Kurt Chinnici, Argand Lighting in Philadelphia, 1800–1845, master’s thesis, Savannah College for Art and Design, 2000.

3. Anonymously authored, and printed in Philadelphia by J. B. Chandler. This pamphlet is owned by the Library Company of Philadelphia. See also “Everyday Actualities - No. VIII,” Godey’s Lady’s Book (March 1853): 97–203, and J. Leander Bishop, A History of American Manufactures from 1608 to 1860 (Philadelphia: Edward Young & Co., 1864), 553–557.

4. See Bruce Sinclair, Philadelphia’s Philosopher Mechanics: A History of the Franklin Institute, 1824–1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974), ix, x, 31.

5. Report of the Twenty-Third Exhibition of American Manufactures (Philadelphia: Franklin Institute, 1853), 21.

6. The Crystal Palace, and Its Contents: Being An Illustrated Cyclopaedia of the Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (London: W. M. Clark, 1852), 294, 295.

7. For a discussion on the firm and its statuettes, see Carol A. Grissom, “The Zinc Statuettes of Cornelius and Baker,” Winterthur Portfolio, 46, no. 1 (Spring 2012): 25-61, See also her book Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850–1950 (Delaware: University of Delaware Press, 2009).

8. Report (Philadelphia: Franklin Institute, 1856), 57.