Mementos: Jewelry of Life and Love

There are jewels that take our breath away, flights of fancy wrought in precious metals and fine gems admired not only for their value but for their artistry (Fig. 1). Then there are pieces we choose to wear every day: a fashion necklace that makes a playful statement or classic pearl earrings to match a suit, around which we spin anecdotes about where we found them or when our betrothed “popped the question” (Fig. 2). Whether a fashionable accessory or a family heirloom (Fig. 3), jewlery helps us tell stories about ourselves, our families, and our lives.

This spring Historic New England presents Mementos: Jewelry of Life and Love, at the Eustis Estate in Milton, Massachusetts. Shown with complementary textiles, portraits, and photographs, the exhibition draws on Historic New England’s collection of approximately 2,500 pieces of jewelry and related adornment, spanning the eighteenth century to the present day.

|

Organized in themes that echo the storytelling power of jewels—Celebrate, Remember, Tour, Collect, and Create—the exhibition showcases souvenir charm bracelets, diamond brooches, hair necklaces, and fashion jewelry worn in New England. Exemplifying Historic New England’s jewelry collection is a silver bracelet that belonged to Lydia Chace of Providence, Rhode Island. It was possibly a gift from her mother, Ella (Fig. 4). Engraved 1884 dimes, polished first to remove their original markings, were suspended from the silver cuff to document three generations of the Chace family—cousins and aunts, grandfathers and sisters. This is far more than a love token, even though these coin jewels are often given that name. This bracelet was an heirloom, a wearable family tree.

Celebrate features presents for new babies, class rings, and the many ways to say “I love you” with jewelry. Among them are a pair of gold bands (Fig. 5) that Stephen Borkowski and his partner, Wilfrid J. Michaud Jr., fell in love with when they saw them in the window of Tiffany & Co. in Palm Beach, Florida. Once they returned to Boston, they made a trip to Tiffany’s at Copley Place, where they had the jeweler customize each band with their initials and the dates of their decade of life together. When Wilfrid died in 2002, Stephen added another engraving, UBLUD (“united by love until death”), inspired by the classic 1968 movie Mayerling.

Elizabeth Gilbert’s parents commissioned a portrait of her holding her silver and coral rattle in 1839 when she was ten months old (Fig. 6). Many believed that coral had protective powers and its smooth texture also made it a popular choice for teething handles on rattles. When conserving the rattle for the exhibition (Fig. 6a), Fran Wilkins, a Mellon Foundation conservation fellow, discovered a fragment of the original coral hidden in the silver rattle. Her re-creation skillfully matched the original coral’s color. Unfortunately the silver end-cap visible in Elizabeth’s portrait disappeared before the rattle came to Historic New England.

Tour highlights New Englanders’ love of place and keepsakes of favorite vacation retreats and exotic locales. When naval paymaster Samuel T. Browne returned to Rhode Island from Japan in 1867 he brought an unusual braided straw chain and ivory pendant (Fig. 7) back with him. The oval plaque is set with a realistic silver fly, complete with gemstone eyes. Browne most likely used the piece as a watch chain and fob but a later owner turned it into a necklace.

Remember features examples of mourning gems passed down from generation to generation in memory of loved ones. An unusual double mourning ring (Fig. 8) commemorates husband and wife Zephaniah and Hannah Leonard, who died on the same day in 1766. Beneath the coffin-shaped crystals lie tiny drawings of skeletons. Family tradition held that the eldest daughter of the eldest son in each generation would inherit the ring.

Collect tells the stories of six women and the jewelry that had special meaning. Among them is Sara Norton, the daughter of Charles Eliot Norton, the first professor of the history of fine arts at Harvard University and friend to many late-nineteenth-century cultural luminaries. She was her father’s near-constant companion and the editor of his published letters. As portrayed in a 1910 portrait by English artist Hugh de Twenebrokes Glazebrook (Fig. 9), she might still have been in half-mourning for her father, who died in October 1908. The ear pendants she wore for her portrait are amethysts suspended from natural pearls, made by New York City jewelers Black, Starr & Frost, which she kept in a box marked with her hand-drawn monogram (Fig. 9a).

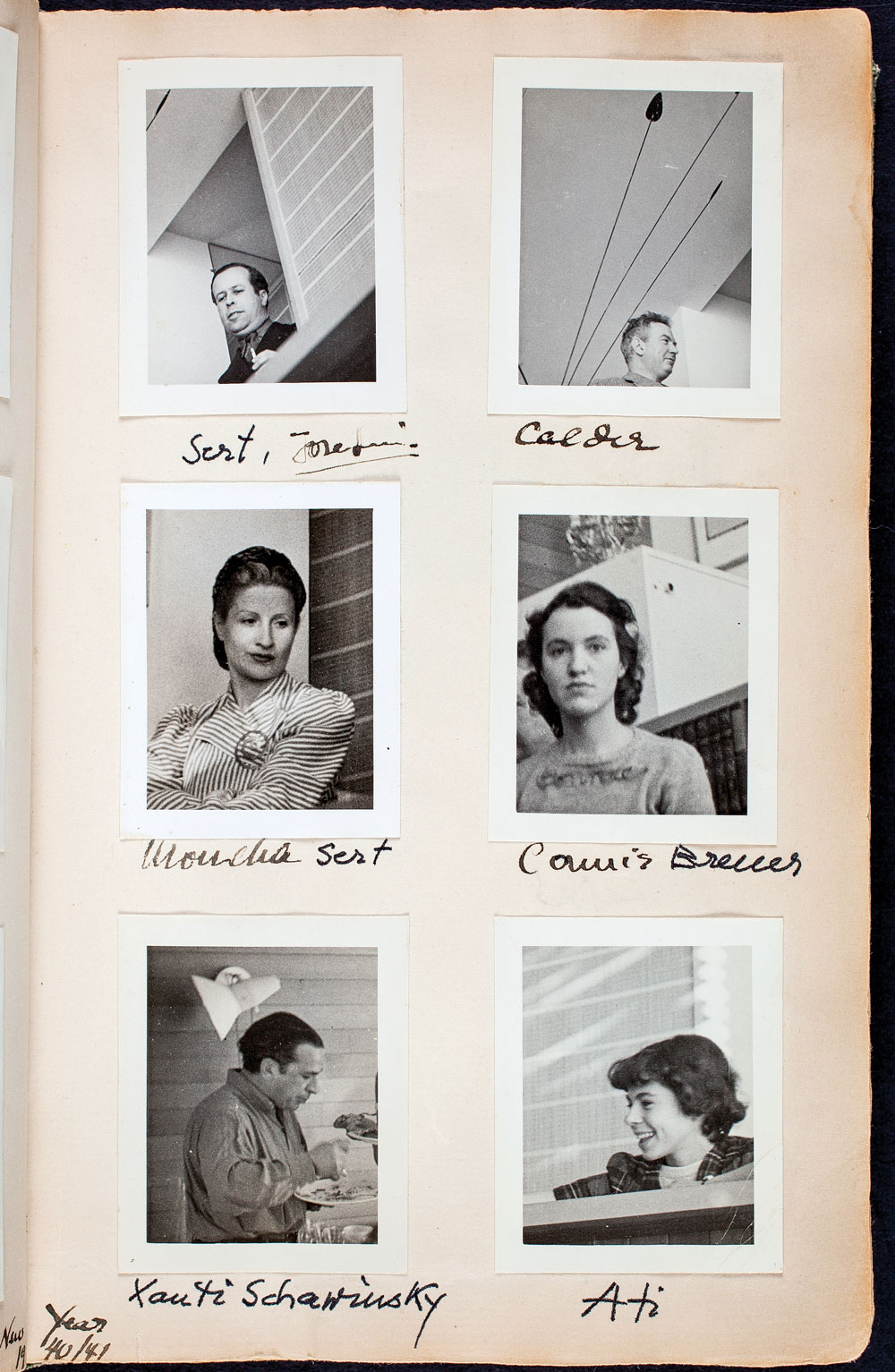

Fourteen-year-old Ati Gropius, daughter of Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus School in Germany, received a special present when she and her parents attended a New Year’s party at the Massachusetts’ home of neighbors Connie and Marcel Breuer’s in 1941. Her mother, Ise Gropius, recorded the event in annotated snapshots she pasted into their guest book (Fig. 10). Among the distinguished guests were New York gallery owner Marion Willard and sculptor Alexander Calder and his wife, Louisa. The party coincided with the first exhibition of Calder’s jewelry at Willard’s gallery. Since the 1930s, Calder had been making jewelry for his friends and family, and nearly all the women who attended wore Calder’s distinctive hammered wire jewelry. He often personalized these items, using the name or initials of the recipient as design components. At the party, or soon after, Ati received a brooch of her own, worked in brass and silver that spelled out her name. The brooch, now owned by Ati’s daughter, is the only item on loan to Historic New England for this exhibition (Fig. 10a).

Create investigates New England’s critical role in jewelry production, including costume jewelry for which the region was known, and the unique products of artisan jewelers from the 1800s to today. When costume jewelry became popular between the First and Second World Wars, designers intended it to resemble its precious counterparts. One of the first designers to embrace costume jewelry, Coco Chanel, said, “When you make imitation jewelry, you always make it bigger.” These pieces often copied, or at least hinted at, luxury jewels. New England’s manufacturing jewelers dominated the industry. Coro, Trifari, Little Nemo, L. G. Balfour, all founded before 1920, made stylish adornments available to a wide range of consumers.

Alfred Philippe, head designer at Trifari, created a bracelet (Fig. 11) to look similar to fine jewelry by Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels, where he had once worked. Trained in Paris, he helped to improve the quality of design and execution in American costume jewelry.

Boston jeweler Frank Gardner Hale brought techniques he learned from English Arts and Crafts jewelers back to his hometown. His leadership in the Society of Arts and Crafts Boston profoundly influenced American jewelers. A brooch that unites sinuous gold vines with a green tourmaline from Maine (Fig. 12) is typical of Hale’s style.

These are some of the more than one hundred thirty jewels included in Mementos: Jewelry of Life and Love. Shown with complementary textiles, portraits, and photographs, these objects illuminate a facet of New England’s past. The exhibition opens on May 17, 2017 at Historic New England’s Eustis Estate Museum in Milton, Massachusetts, and will remain on view through January 7, 2018. For more information, visit www.historicnewengland.org.

Laura E. Johnson is associate curator at Historic New England, with main offices in Boston, Milton, and Haverhill, Massachusetts.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.