Unmasking A Clock Dial: The Gentle Art of Cleaning A Clock

Cleaning Time! A WINTERTHUR PRIMER

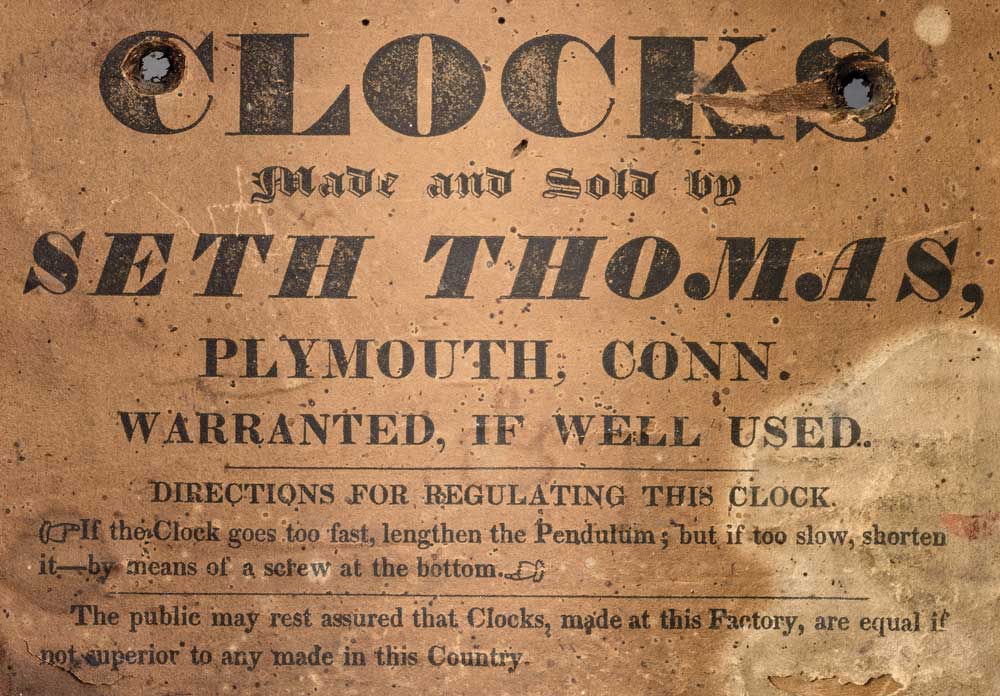

In preparation for a recent exhibition at Winterthur, we inspected one dozen small clocks to assess their conservation needs.1 The label inside a standard pillar-and-scroll shelf clock made by Seth Thomas’ manufactory (Fig. 1) amused us. It declares the clock “warranted, if well used,” meaning well maintained and well treated (Fig. 2). This painted dial clock was produced during the first boom-time of American clock making, when Seth Thomas, Eli Terry, and other Connecticut manufacturers shipped inexpensive and reliable clocks to markets around the nation. But the label is also a warning to would-be tinkerers. We found no instructions for cleaning clock dials and mechanisms in household servants’ manuals of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although they teemed with recipes for polishing metals, glass, and wood furniture. Clock movement maintenance was, and remains, an area of professional expertise.

We might suppose that antique clocks were regularly taken to local clockmakers for cleaning, but human hands and cleaning products have left ample evidence to the contrary. Even fingerprints from past owners sometimes remain etched on the brass plates. In addition to these traces, metal surfaces have been negatively affected by ingredients used in historic recipes to keep brass and silver gleaming. Polishing powders commonly used included cream of tartar, rottenstone, or even potassium cyanide in water, or soft soap with ammonia solutions, but modern chemicals have also left their mark.2 Although well intentioned, the use of chemical cleaners over generations can significantly alter a clock’s metal elements, often to the point of no return.

Understanding previous cleaning techniques in order to attempt to reverse their negative effects was our challenge for Winterthur’s tall clock with a dial signed by Benjamin Chandlee (Fig. 3). Some might describe the dial’s patina as original or “untouched,” but the brass dial and silvered elements were nearly the same color as the walnut case. Just the faintest trace of green copper oxidation was visible, and the thin layers of silvering could only be detected by scientific instruments. Rather than aging through gentle neglect, these metal surfaces became uniformly coppery-pink due to assiduous, harmful cleanings that resulted in a zinc depletion that altered all the surfaces especially in the formerly silvered areas (Fig. 4). Before attempting to improve the dial’s appearance, conservation fellows Lauren Fair and Jessica Arista identified black fill material in the dial’s engraved numbers and signature boss as pine resin, beeswax, and bitumen. Protecting those delicate original black fills was a priority that further complicated their treatment. They also determined that gentle elbow grease and cotton swabs alone would not return a warm, yellow surface to the brass.

After disassembling all the dial components, gentle chemical cleaners tailor-made in our lab were imbedded in a gel and selectively applied.3 Gradually the brass elements released the contents of their corroded surfaces and cleaning continued. The black-filled numbers received protective barrier coatings and any losses were filled in with acrylic paint. For the elements originally silvered, we selected a water-soluble gilding method using palladium leaf for its fully reversible quality and gentle, aged look.

This experimental, time-consuming process yielded an elegant clock dial, once again harmonious with its original case (Fig. 5). While our method was designed specifically for this particular brass dial, thankfully, the painted and varnished wood dials favored by Seth Thomas and other manufactories are less complicated to clean. The lesson here is that residues from chemical cleaners can continue to alter surfaces even if they are invisible. Other than careful dusting, antique clocks are best cleaned by professionals.

Ann K. Wagner is curator of decorative arts at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, and co-curator, with Josh Lane, of Striking Beauties: American Shelf Clocks and Timepieces.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available on Incollect. Visit www.Winterthur.org for a full listing.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Commercial polishing products often contain ammonia, which should be avoided when cleaning brass. The pH of any cleaning solution needs to be considered when cleaning copper alloys, as highly acidic solutions can solubilize zinc and weaken the metal substrate.

3. The cleaning process we selected is not typical, but is currently being explored by conservators.