Tribute to Abbott Lowell Cummings

Abbott Lowell Cummings passed away recently at the age of 94. A leading light in the field of architecture and historic preservation, he mentored three generations through his teaching and scholarship, while conveying a boundless enthusiasm for the material. He relished in engaging others, particularly young people, in conversation, and sharing his passion for the built environment.

I knew Abbott through my tenure at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA; now Historic New England) in the 1980s; I am forever grateful for the numerous times our paths crossed. I have asked a number of the hundreds of individuals who Abbott thought of as friends and colleagues to contribute their remembrances of this very special individual who touched the lives of so many. I am sure you will smile while you read the contributions below from Bernie Herman, James Garvin, Lorna Condon, Earle Shettleworth, Jane and Richard Nylander, Bill Hosley, Donald Friary, Phil Zea, Bill Flynt, Bob Trent, Brian Pfeiffer, Anne Grady, Ed Zimmer, and Marilee Boyd Meyer. Abbott requested that Richard Candee write his obituary, which follows the other tributes.

As Bill Flynt writes below, “We have lost a giant in the field whose legacy will continue to inspire all who had the good fortune to make his acquaintance and/or learn from his research and publications. In the words of my grandfather [Henry N. Flynt, cofounder of Historic Deerfield], 'he was a gentleman and a scholar.'”

There is a memorial service scheduled for Abbott on

October 12, 2017 at 3:00 p.m.: Old West Church, Cambridge Street, Boston, Mass.

Reflections

“There were a number of important gifts [to SPNEA in 1955-56] and there was also the acquisition of a large supply of the intangible elements which accelerate progress, namely youth, energy, knowledge, experience, initiative, and imagination. These intangibles have come to us through Mr. Little’s great success in having engaged young Mr. Abbott Lowell Cummings as assistant director.”

—Buchanan Charles, librarian, SPNEA, 1956

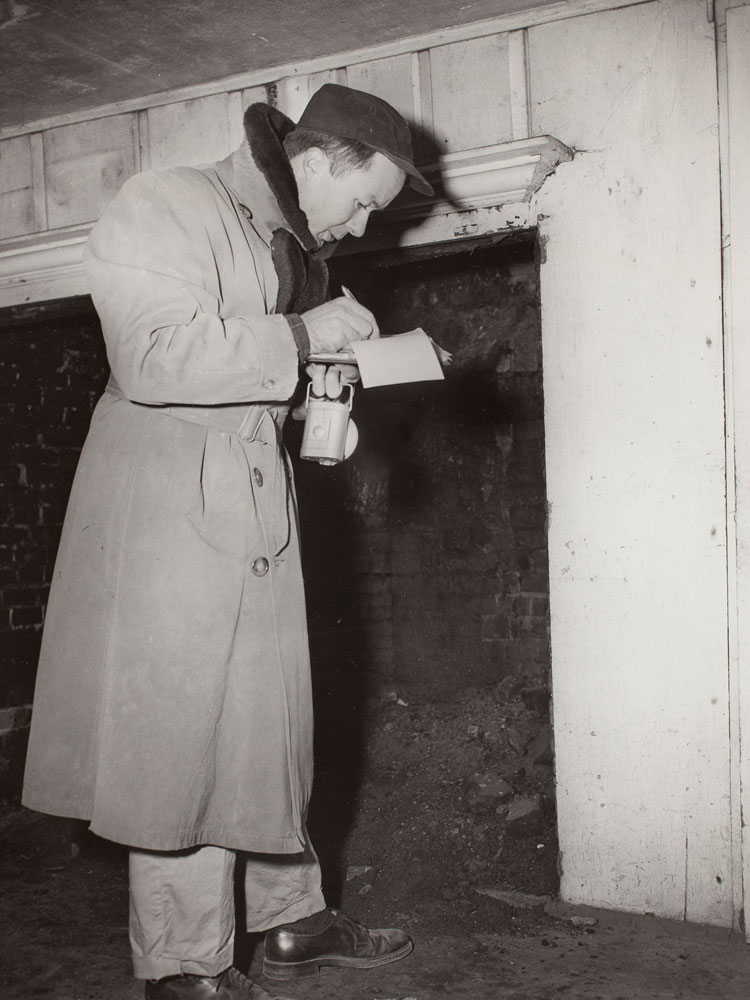

In 1955, Bertram K. Little, director and corresponding secretary of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, hired Abbott Lowell Cummings as assistant director. Abbott’s responsibilities included overseeing the interpretation and preservation of the organization’s numerous historic houses and editing Old-Time New England, the quarterly bulletin. Abbott also took on the role of preservation advocate travelling extensively throughout New England to advise communities about preservation efforts and their historic sites.

Abbott continued at SPNEA for the next twenty-eight years, and his tenure was filled with accomplishments and activities too numerous to mention here. But I do want to address just one aspect of his work: his devotion to the organization’s Library and Archives and his extraordinary efforts to acquire rare and important items for its collection. Perhaps his most important acquisition was in 1965, when he purchased a set of measured drawings that were, in his words, of “cornerstone significance”: the drawings of the 1737 Hancock House in Boston, which architect John Hubbard Sturgis made just before the house was demolished in 1863, following a preservation battle. They are considered to be the first set of measured drawings of an American domestic building.

As a result in part of his own efforts, Abbott could write in 1974: “the student of New England architectural history will find in the Library an almost limitless range of documentary source material, without recourse to which no serious study of the subject can be considered definitive.”

—Lorna Condon, Senior Curator of Library and Archives, Historic New England

Abbott epitomized grace, intellect, and generosity of spirit. Our paths converged in the founding days of the Vernacular Architecture Forum when Abbott lent his name and reputation to our collective enterprise. Abbott possessed “architectural creds” that lifted us all. His great and enduring The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay (1979) had just been published, shaping new methodologies and interpretations that would guide the next generation of fieldwork and scholarship. Abbott inspired us. And, he made us laugh as we learned. I recollect standing with Abbott, Cary Carson, Dell Upton, and others in the stripped interior of a 17th-century dwelling with drawings from Framed Houses pinned to the walls. One of our number noticed a discrepancy between the architectural fabric in front of us and the graphic. “How distressing,” Abbott sighed, “but there is so much to learn.” In that moment, Abbott taught us how to learn with humility and precision. That moment was the gift of a lesson about how we know and share the universe of ideas. That moment was the essence of Abbott.

— Bernard L. Herman, Department Chair, American Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Abbott was a visionary and champion for New England architecture and history. His passion for all things antiquarian inspired three generations of students and acolytes. Likening the work to monks keeping the light of civilization alive in dark times, his influence was magnetic and radiant.

Abbott’s scholarship breathed life into three distinct domains. His work on bed-hangings underscored the importance of original intent—the idea that understanding interiors depends on the fugitive aspects of fabrics and upholstery. His work on probate inventories helped launch a scientific approach to period restoration. Thirty years in the making, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625–1725 is one of the most important books on any aspect of American architecture—a gold standard.

Abbott was the founding spirit of of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the American and New England Studies Program (Boston University), and Historic New England’s Vale Program (1979), which lives on as the Program in New England Studies.

Abbott was a thought leader and moral compass in a world that needs both more than ever.

— William Hosley, Terra Firma Northeast, Enfield, CT

I remember the day in 1963 when Abbott and Bertram Little paid a visit to the fledgling Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth, New Hampshire—then a “preservation project” of uncertain promise, not yet a “museum.” Given my youth and limited background at that time, I had adopted Abbott’s engagingly written 1958 booklet Architecture in Early New England as my primer, and I was in awe of its author. I recall Abbott’s kindness and encouragement at our first meeting. In the half-century that followed, Abbott repeated that kindness and encouragement many times as a teacher and colleague, and multiplied the benefit of his little booklet through the voluminous contributions he made to our understanding of New England’s material culture.

Abbott embodied and defined standards of scholarly rigor, integrity, and colorful verbal expression. He posed questions that needed to be answered even when others had complacently assumed that the answers were in hand. He recognized research sources that others had ignored. He conveyed understanding through powerful reasoning and explanation. He presented his findings in precise and memorable language that no listener or reader ever forgot. The gifts he bestowed as a scholar, teacher, and friend will long suffuse and enrich our lives.

— James Garvin, State Architectural Historian, Retired, N.H. Division of Historical Resources

Thinking of Abbott

Son of New England

Man of prodigious memory

Inexhaustible Seeker

Inspiring Leader

Meticulous Scholar

Always eager to learn more

Devoted Antiquarian

Effective Preservationist

Enthusiastic Speaker

Constant Teacher

Mentor of Many

Entertaining Raconteur

Lover of Limericks…and Manhattans

Always Welcoming, Caring, Sharing

A Dear Friend

— Jane Nylander, President Emerita, Historic New England

Having worked with Abbott for seventeen years at “the Preservation Factory,” as we sometimes called SPNEA, now Historic New England, I had the honor to give the summary remarks at the day long symposium held in his honor before he was presented with the Henry Francis du Pont Award in 1998. I can’t find the notes I took that day but it doesn’t matter because my overriding memory is how each speaker fondly recalled how he or she had been inspired by Abbott. Abbott was many things, but above all, he was a mentor and teacher to both young and old. He was full of knowledge which he selflessly shared and he was always open to new ideas. His enthusiasm was contagious, not just for architecture for which he is most well-known but for anything that piqued his interest. He was very serious at times but hilarious at others. He taught us all the importance of documentation and the value of both curiosity and humor.

— Richard C. Nylander, Curator Emeritus, Historic New England

When Abbott Cummings and I first met in 1965, it was immediately clear that he was an able scholar, a sharp observer, and a magnetic personality. I knew that he would be a mentor and a boon companion. Rural Household Inventories had just been published and was exerting strong influence on research on domestic life and social history in those days of community studies. Abbott’s knowledge of New England architecture was well known—both the Federal period and the work of Asher Benjamin, on whom he had written his dissertation, and the seventeenth century, in which he was making pathbreaking discoveries in timber frame construction, roofing and cladding, interior and exterior paint. We learned something from Abbott in every conversation. It was always a treat to walk around Boston or any New England town with him. Abbott’s high standards in research and scholarship and his dogged determination to get to the bottom of any issue informed his own work, as well as that of so many students and colleagues. And he was great fun, unmatched as a raconteur!

—Donald R. Friary, President, Colonial Society of Massachusetts

During his long and fruitful life, Abbott contributed much to the fields of architectural history and historic preservation. His most enduring legacy will be his role as an educator. Through his research, lecturing, and publishing, his college and graduate school teaching, and his mentoring of students and colleagues, he instilled in us a deep appreciation for the built environment and material culture of New England. Abbott’s infectious enthusiasm, generous spirit, insatiable intellectual curiosity, and rigorous scholarship enriched and inspired all who knew him.

— Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Maine State Historian

For all of the New England places that Abbott might have called home, we have been blessed in Deerfield [Mass.] for years to have him as our neighbor just five miles down the road on Hillside Drive. If one seeks a model for merging vocation and avocation, look no further than Abbott Lowell Cummings. He sets the standard for bringing such a genuine and high level of inquiry to almost any subject, from first-period architecture to the National Football League, with such enthusiasm that a personal conversion experience was unavoidable. Abbott was so focused on process as a means of understanding the topic at hand that he could engage with anyone—robed academics, potential supporters, local politicians, trades people at work on the buildings he loved—essentially all gathered to solve social issues through the preservation of significant human places. Understanding the past and its occupants was Abbott’s mission; his passion was teaching about them—anywhere. I am personally sorry that the one place I never ‘experienced’ Abbott was in a formal classroom. Even failing that, I remember Abbott as one of the best, inspiring teachers I ever encountered. I think that it is time to reread Framed Houses of the Massachusetts Bay so that I can hear his voice through his words.

— Philip Zea, President, Historic Deerfield

I met Abbott by chance in 1970 on my first visit to the Harrison Gray Otis House, headquarters of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. While pondering architectural details, I overheard Abbott describe to a student how the decorative elements of a cornice were achieved in plaster. With limited architectural experience and the naïve courage of a novice, I interrupted to ask why he thought plaster rather than carved wood. I was not aware it could have been a foolish question and would never have known it from his reply. Abbott had that rare ability to make everyone around him feel insightful and intelligent. He questioned me briefly on my interest in such details, learned that I was a student at Boston University, and urged me to register for his graduate seminar in New England architecture. I explained that I was only a sophomore, a worry he dismissed with a gentle wave of his hand and a familiar phrase, “Don’t trouble yourself about that dear boy, just sign up.” I did, and it changed my life. I knew I loved architecture but did not know what to do with it. Abbott opened to me a way of seeing and understanding architecture, one which is complex and more engaging than a simple history of design. He taught me to dig into deeds, probate records, letters, diaries—any source that might reveal the particular truths of individual buildings. Even more important, his example gave permission to infuse scholarship with a deep, animating love of the subject. Words of thanks are inadequate for such a profound gift.

— Brian Pfeiffer, Architectural historian, founder, ArchipediaNewEngland.com, and former Vice President for Building Conservation Services at SPNEA.

Being in the presence of Abbott was always a treat as invariably there were lessons to be learned as he engaged in conversation, analyzed an architectural fragment, or studied a building he was asked to examine. He was thoughtful and interested in your opinion, even if he had a better explanation. Those of us living in the Connecticut Valley were fortunate to have Abbott retire to the area as he became a familiar presence in the Memorial Libraries and was accessible for conversation, inquiry, and an occasional field trip. On a recent visit to see him with Phil Zea, we were amazed that, though in his early 90s, he honed right in on genealogical research as it pertained to a local joiner we were discussing. His intellectual wheels just kept on rolling in spite of his advanced years. I will miss his encyclopedic and inquisitive mind for all things pertaining to New England architecture, his support and interest in the latest dendrochronology findings, the twinkling eyes, his ready smile, and dry humor. We have lost a giant in the field whose legacy will continue to inspire all who had the good fortune to make his acquaintance and/or learn from his research and publications. In the words of my grandfather, "he was a gentleman and a scholar."

— Bill Flynt, Architectural Conservator, Historic Deerfield, Deerfield, MA.

Abbott was universally loved and respected (except, perhaps, by a few homeowners whose houses he could not date to their liking). So many people were touched by his kindness, humor, enthusiasm, insight, scholarly acumen, and grace. Abbott inspired all kinds of people, most notably those he mentored, including me. As an uncertain older student, I was electrified by his presentations in his First Period Architecture course and never looked back as I pursued my own interest in 17th-century buildings.

It was for Abbott that I became, as he said, the midwife to the current dendrochronology in New England, after he lamented the failure of his earlier effort. My first impulse when making a discovery was to tell Abbott, even if it was delivered by iPhone from the upper reaches of scaffolding at the House of the Seven Gables where Bill Finch and I uncovered an interesting piece of early window trim. His enthusiastic reaction made the discovery sweeter.

Abbott had something approaching clairvoyance when evaluating an old building. Those who read his professional papers at Historic New England in the future will encounter his lucid writing style and exemplary description of so many New England buildings (every one he ever saw, I believe). Those who knew him may find comfort in experiencing the familiar “voice” again. I will remember Abbott as I use my well-thumbed copy of Framed Houses or consult my off print of Massachusetts and Its First Period Houses, its binding falling to pieces.

—Anne Andrus Grady, Architectural Historian, independent scholar

I first met Abbott when I took his famous early architecture course in about 1970. This was in the Otis House basement [SPNEA's headquarters]. I recall he used glass slides from the 1920s. We also took field trips to Salem. He was obviously brilliant and funny. I kept in touch with him through the years and he always listened intently to what I was saying. His usual greeting was "Here we are, my boy, aren't you looking virile and trim!"

— Robert Trent, independent scholar

My first contact with Abbott was a summer internship at SPNEA in 1973, between my college graduation and beginning the BU American Studies program. On my first day, Abbott directed me and another intern to transcribe a 17th century manuscript deed for the Pierce House in Dorchester. We struggled with the handwriting and the creative spelling. We knew nothing of the arcane and unfamiliar phrasing in which “convey” was followed by every synonym imaginable. We argued over which was punctuation, and which were flyspecks. After several hours of work, we were fairly confident we’d mastered the brief document. Then Abbott came by, marveled at the fun of working with early texts, and read us the deed aloud as if he was reading from the Boston Globe. From that internship through his signature on my dissertation in 1984, Abbott was a role model and mentor, especially in his contagious joy and excitement in research and teaching.

— Ed Zimmer, Historic Preservation Planner, Lincoln, Nebraska

I am so saddened to hear of this sparkly, elfin, passionate leader's passing. He was such a pied piper to this young (unaffiliated independent townie) historian and I continue to feel so blessed at being a member of the inaugural Vale Program at SPNEA. Abbott never once made me feel "less than" because I wasn't in a masters program somewhere, but instead let me know that citizens with passion are just as valuable if not more so to the greater society and the preservation cause—a sentiment that remains important today.

Abbott was a great model because his passion for history and research was pure—unadulterated by big money, development dealings, kick-backs, and having a great concern for what will be erased with some of the compromises seen by today's historical commissions.

Where are our future leaders who have this kind of commitment to our culture and historical context? We need him now more than ever. But let's hope that his seed-planting has garnered another generation of watchdogs in his name before we become homogenized, sterilized, and generic. The mantra "History Matters" will live on, carrying his lessons, observations, idealism, and passion in an effort to respect and protect our collective story.

Rest in peace, Abbott.

— Marilee Boyd Meyer, Independent scholar

Formal Obituary

Abbott Lowell Cummings 1923 – 2017

Abbott Lowell Cummings, the leading authority of 17th and early 18th century (“First Period”) architecture in the American northeast and author of The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay (Harvard Univ. Press, 1979) died early May 29 at age 94 at The Elaine Center, Hadley, Massachusetts. An outstanding teacher at Boston University, Yale University, and U. Mass Amherst mentoring dozens of young scholars, he asked me many years ago to memorialize his life and scholarship when the time came.

Born in St. Albans, Vermont, on March 14, 1923, the son of a Congregational minister and sometimes supporter of Norman Thomas, he spent much of his youth with his beloved paternal grandmother in Southington, Connecticut. This old Yankee helped to form his love of genealogy and appreciation of New England’s past. It was she, too, who gave the teenager a membership in the Society for Preservation of New England Antiquities.

The budding art historian was educated at The Hoosac School (1936–1941), Oberlin College (BA 1945, MA 1946), and Ohio State (PhD 1950), then one of the few universities offering American architectural history. He soon learned discretion in speaking of his research when, in 1948, Prof. Henry Russell Hitchcock published without credit Cummings’ new discoveries on the design and building of the Greek Revival Ohio capitol.

From 1948–1951 he taught at Antioch College, while finishing his critical study of the Federal era building guides of architect Asher Benjamin. Thereafter, he accepted a position as assistant curator for the American Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art until, in 1955, he was hired as assistant director of SPNEA, and editor of its journal, Old-Time New England.

I met Abbott Lowell Cummings in the early 1960s when I was an Oberlin sophomore in a summer program at Historic Deerfield on a fast-paced tour of Boston’s buildings. Given our mutual history at Oberlin he encouraged me to seek out his old professor—Clarence Ward—and urge him to give me a class on American architecture. It set me on my own career in architectural preservation.

For his Master’s Thesis at Oberlin, “Documentary Histories of Seventeenth Century Houses in Massachusetts Bay,” Abbott noted that stylistic a consistency through the 17th century and a time “lag” for adopting new design ideas was “confusing to the historian in his attempt to establish a system of dating for the houses of the 17th Century.” He carefully sifted through the documentary evidence of 70 houses—many of them no longer standing— in the Commonwealth with detailed notes on the “condition” and plan development for those still extant. This was followed—in typical Abbott Cummings fashion—by an appendix of 10 building contracts and similar documents, and a full secondary bibliography. This was in 1946.

I mention this first attempt at his favorite topic to show how long ago his Framed Houses actually began. Over the next 34 years Abbott continued his research about what really happened to these (mostly) surviving houses and what changes in structure or style occurred. Certainly, that is what he was doing while he worked at The Met, documenting all the rooms that George Francis Dow helped install in the 1920s.

Joining the SPNEA in 1955 as assistant director and editor he was allowed one day a month for personal research to delve into not only the oldest surviving houses but documents underpinning both his Framed Houses and other books and articles on bed-hangings, probate inventories, and wallpaper.

What most folk never knew, was that Abbott thought he had his masterwork (Framed Houses) nearly completed sometime in the late 1960s. He had all the documents, had been to see all the early houses in the Bay Colony, and had large chunks of writing well advanced. He had also searched out some of the (virtually unstudied) English buildings of the early 17th century that might have provided prototypes for Massachusetts work. Time and experience would postpone publication.

He and I spent several summer vacations trotting around England during the late 1960s and early 1970s looking at areas where “his carpenters” had come from, seeking out his famous “prototypes”—houses sharing similarity of form or construction to the earliest Mass. Bay homes. We spent several summers in the hands of Freddie Charles and his family, one summer looking at examples with Ron Brunskill, and another year attending a VAF meeting and tour with all the early VAG members. His particular interests brought new attention to the 17th-century timber framed vernacular that British scholars had considered one of the less interesting periods of their vernacular.

There, too, in the late 1960s he met Cecil Hewett—the secondary school art teacher with an antiquarian bent for drawing the structural joint systems of timber-framed buildings. Hewett revolutionized the dating of those English buildings by developing a theory about the chronology of various timber joints and how they “evolved”; this eventually led him to a position with the Greater London Council Buildings Division in 1972.

In what I always considered one of the clearest acts of intellectual honesty, Abbott essentially threw out his old manuscript and—getting a grant to bring the whole Hewett family over to Massachusetts for a summer—revisited all the major houses so Hewett could draw their framing details and educate Abbott about framing in this new theoretical system that linked the New World to the Old.

If computers had been more advanced in the early 70s, we might also have had a chance at tree-ring dating in Framed Houses. It has always been a disappointment that his discovery of the 1590s droughts in the chimney beam of the 1660s Gedney house in Salem did not evolve as easily into the general practice of dendrochronology that we know today. He saw it clearly as a potential—but the conservatism of the New Mexico experts who claimed New England’s weather was too “complacent” for measurement killed the idea for two decades and the coming of computers.

His intense study area was only Massachusetts Bay Colony with its great abundance of First Period buildings—more perhaps than anywhere outside Europe. And, as he remained somewhat secretive and justifiably paranoid that someone would scoop his research, he was perfectly happy to let others explore the 17th-century houses elsewhere in the state and region.

Thus, in the mid-60s when Cary Carson, a young Harvard graduate student, and I were both hired to explore the 17th-century architecture of Plymouth Colony for Plimoth Plantation museum, I replicated Abbott’s method of looking at the documents and tried to find patterns from the surviving houses and their inventories. He published my “Documentary History” of Plimoth’s early buildings in Old-Time New England. He also “gave” me my dissertation topic—the very few First Period wooden buildings of Southern Maine & NH—because they wouldn’t conflict with his study.

Abbott always claimed that his was “an old fashioned” history of the subject. Its geographic specificity—Massachusetts Bay—did make Framed Houses into something akin to Norman Isham’s studies of Rhode Island and Connecticut earliest buildings written much earlier in the 20th century.

Taking over as Executive Director of the SPNEA in the difficult 1970s and 80s, he also helped form the American and New England Studies Program at Boston University.

His interest in geographic specificity of early timber framing continued when he was lured to Yale University as the Charles F. Montgomery Professor of American Decorative Arts (1984–1992). Both Connecticut and New Netherlands offered whole new areas with buildings for which he might ask the same questions but elicit different results. I vividly remember a wonderful symposium at Yale where John Demos conjured up a mythical Dutch Carpenter named “von Cummins” to help explicate all the Dutch influences on Connecticut framed buildings.

Retiring from Yale to a home in South Deerfield, Massachusetts, with his sister’s family, he spent his early retirement compiling the Descendants of John Comins (ca. 1668–1751) and his wife, Mary . . . (Boston: Newbury Street Press, 2001). With a genealogical interest instilled by his beloved grandmother, Abbott served from 1970–73 as a Trustee of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, writing many articles in their magazines; he was a Council member after 2004.

In early retirement he taught again for two years at Boston University and at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst from whom he received an honorary degree in 1998. He was also recognized with the Henry Francis DuPont Award, and awarded honors for his scholarship by the Traditional Timber Frame Research Group, the Vernacular Architecture Forum, the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation, and the American Society of Genealogists American Society of Genealogists.

He was a Life member of SPNEA, the Bostonian Society, the Fairbanks Family in America, and the Southington [CT] Historical Society, a Massachusetts Historical Society Fellow, an Honorary Member of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and served on many boards and overseers committee including Plimoth Plantation, the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Historic Deerfield, and others.

He remained a Life Member of the Ancient Monuments Society, an elected member of Society of Antiquaries of London, the American Antiquarian Society, the British Vernacular Architecture Group, and was founding president of the Vernacular Architecture Forum whose highest prize for scholarship remains their Abbott Lowell Cummings Award.

Abbott is survived by his devoted nieces and nephews: Abigail Cummings of Arlington, VA, Carla Cummings of New York City, Jonathan Cummings, Jr. of Bethesda, Maryland, Justina Golden of Florence, MA and Scott Cummings of Austin, Texas.

— Richard M. Candee, Prof. Emeritus, American & New England Studies, & Preservation Studies Program, Boston University