“Mr Willson of NH” and His Remarkable Watercolors

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

|

|

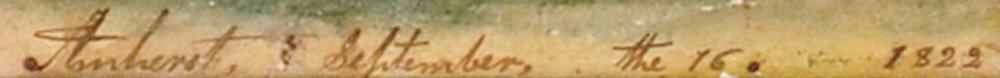

| Fig. 1a: (details) Inscription on Stratton portrait in a later hand reads: “Amherst, September the 16th 1822 Drawn by, Mr Willson: NH.” Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.; Gift of Stephen C. Clark (N0252.1961). Photography by Richard Walker. |

T

he name of “Mr. Willson of NH” has long been associated with an outstanding body of watercolor portraits executed in the state of New Hampshire during the third decade of the nineteenth century. Of the fifteen plus portraits attributed to his hand, none were signed by the artist and only one portrait makes a reference to who that might be. It is a portrait of an Amherst, New Hampshire, resident, Barnard Stratton, whose name appears at the top of the canvas (Fig. 1). Along the lower border, in a later hand, are inscribed the words “drawn by Mr. Willson NH; Amherst; September the 16th 1822” (Fig. 1a). Hence the name by which the artist is referred to this day.1

There is compelling evidence that “Mr. Willson,” was none other than Lyman Parks, also known as “James Wilson.” Born in Russell, Massachusetts, in 1782, Parks was a man of sophistication and breeding who had demonstrated an uncanny ability to render a likeness from early childhood. As an adult, he put these innate skills to work as a counterfeiter of bank notes, needing to support his growing family after a series of financial setbacks. The first recorded instance of his handiwork was sometime in the 1810s when, according to an 1846 article, “Lyman Parkes alias Wilson” was apparently entrapped in the illicit trade of counterfeiting, being threatened with imprisonment for forgery after an individual posing as a bank cashier retained his services to engrave a plate for a well-known Boston bank.2 At that time, there was no such thing as legal tender, and bank notes were essentially promissory notes. Each bank selected what design they wanted and outsourced the engraving to private engravers. Banks also decided what denominations they would issue. These ranged from five and half cents to $10,000. Paper and ink was not standardized either. All these variations provided myriad opportunities for counterfeiters such as Parks to ply their trade. The Federal Government did not begin to regulate the currency until 1862, so for decades the country was flooded with bogus bills, much of them passing from Lower Canada to states as far south as Virginia.

|  | |

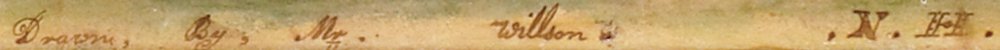

| Fig. 1: Attributed to Lyman Parks (1782-1872) aka “Mr. Willson of NH,” Portrait of Barnard Stratton (born Stowe, Mass., 1796–died Lancaster, Mass., 1870), ca. 1822. Watercolor and ink, 19-1/2 x 15 inches. Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.; Gift of Stephen C. Clark (N0252.1961). Photography by Richard Walker. | Fig. 2: Attributed to Lyman Parks (1782-1872), Portrait of Joseph Colby, born New London, N.H. (1787-1857), 1824. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper, 231-1⁄16 x 19-7⁄16 inches. Watermark: “J. Whatman 1823.” Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, Va.; Gift of Mary Cleveland Sholty in memory of her sister, Patience Cleveland (2005.300.1). |

As there were over five thousand households in New Hampshire with a Wilson or Willson listed in the 1820 Federal Census, using the alias “James Wilson” at least gave Parks cover as he travelled north through New Hampshire to the township of Stanstead (present-day Quebec), at that time the headquarters for those involved in the trade of making bogus money. By the 1830s, Parks was lauded as “the best engraver of counterfeit notes who ever lived; the greatest unquestionably who ever lived in this country.” 3

Given that “Willson” was Parks’ alias, it is not surprising that, despite a concerted search begun in the last century by such leading scholars as Nina Fletcher Little, no advertisements for the services of or further period references to a “Mr. Willson” portrait artist were ever found. It also makes sense that Parks/Willson either was in each town for such a short period that there was not time to place an ad and wait for sitters, or that he likely did not want to draw too much attention to himself, rather relying on word of mouth. Instead, what has proved to be invaluable for identifying works by his hand is his distinctive approach to painting portraits, based on association with the style of the image of Mr. Stratton in figure 1. Each portrait features a single sitter usually against an unadorned background. Sitters are shown half-length, almost life-sized, in a pyramid-like format. Heads are posed in a distinctive three-quarter turn to the right. This artist’s ability to render details is outstanding for the consistency displayed throughout. Every strand of hair, every eyelash, the patterning of the sitters’ vests, and even the folds of their cravats, are captured with so much care and precision that it is clear this is an artist with an unusually steady hand and an uncommon eye for subtle detail. The kind of painstaking attention evident in the portraits illustrated here would also have been a prerequisite skill for engraving bank notes at that time since they often featured vignettes of portraits, ships, birds, and townscapes.4

Aside from a portrait dated 1810 reportedly of a James N. Sinter (current location unknown), the earliest known work by this artist’s hand is the 1822 portrait of Stratton. It is executed on woven paper watermarked “S & C Wise/ 1815.” The yellowing of this paper over time has accentuated what was meant to be subtle highlights such as the white around the eyes, mouth, nose and ears of Stratton’s portrait and may well account for the slightly askew features of the sitter. In contrast, four later portraits of Levi Jones (Currier Gallery of Art), Mary Furber (Museum of Fine Art, Boston), Joseph Colby (Fig. 2), and John Searle (private collection) are done on Whatman Turkey Mill paper. This was an imported English paper that was smoother and stronger and far superior to earlier laid paper, which often encouraged pigment to pool on the page. Favored by many of the leading watercolorists of the early nineteenth century, including Turner and Audubon, it was the best paper available in America at that time. It is undoubtedly due to the artist’s use of good quality pigments and papers that these four watercolors are so well preserved today.

_-_001.jpg) |  | |

| Fig. 3: Joseph Colby (1787–1857), ca. 1845. Tinted daguerreotype. Case: 3-1/24 x 3-3/4 ; image: 2-3/4 x 3-1/4 in. Colby, Colgate, Cleveland Family papers. Courtesy of Colby Sawyer College, New London, N.H. (MS.2001.086). | Fig. 4: Colby homestead front room, New London, N.H., 1981. Colby, Colgate, Cleveland Family papers. Courtesy of Colby Sawyer College, New London, N.H. (MS.2001.086). |

Comparing Joseph Colby’s portrait with a daguerreotype of him about twenty years later (Fig. 3) confirms the artist had an uncanny ability to capture a likeness. Colby first opened a shop in Newburyport, Massachusetts, before setting up shop in his New Hampshire hometown of New London, where he also tended his father’s tavern and served as the local postmaster. He was a decidedly litigious individual who, beginning in 1817, initiated the first of six lawsuits against various individuals before securing a major windfall of $1000 for slander in 1823.5 This bounty is perhaps what prompted him to pose for the portrait, which hung in the Colby homestead from the time it was painted until 1981 (Fig. 4).

| |

| Fig. 5: Attributed to Lyman Parks (1782-1872) aka the Wilkinson Limner, Portrait of Asa Gilmore (born Weston, Windsor, Vt., 1802–died Tecumseh, Mich., 1874), 1825. Oil on scored white pine panel, 26-1/2 x 23-5/8 inches. Weston Historical Society. Weston, Vt. A label previously adhered to the front of this panel read: “Asa Gilmore, born in the old Gilmore house January 2, 1802. Picture painted by an inmate of Charlestown [Massachusetts] State Prison.” |

In June of 1824, three of “Mr. Willson’s” sitters were in the New Hampshire state capital of Concord. John Searle from New Chester and Levi Jones from Union were there representing their respective districts at the General Court. Joseph Colby’s presence in the capital is confirmed by a receipt for his room and board at the Stickney tavern. With its stately grounds and spacious assembly rooms, this tavern was considered one of the best in the town and an important crossroads for travelers passing through New Hampshire at this time. Stagecoaches leaving from Essex Coffee House, Salem, Massachusetts, would pass through Haverhill, Massachusetts, and Chester, New Hampshire, and arrive in Concord in time to connect with stagecoaches en route north to Plymouth, Hanover, and Haverhill, New Hampshire.6

The Stickney tavern was also known to have accommodated a portrait artist or two. In 1819, John Samuel Blunt and William Codman placed a joint advertisement offering portrait, landscape, and fancy painting from a room there.7 Situated on Court House Hill, it was also a favored spot for out-of town members of the General Court for Representatives like Searle and Jones. They, too, may have been guests there when they posed for their portraits. Alas no guest registry for the period has survived.

Regardless, it was surely no coincidence that same month three “Willson” sitters were in Concord, a cache of $3,700 in counterfeit notes was found in a shed adjacent to a tavern in the same town.8 Could Parks have been posing as “Mr. Willson” the portrait artist whilst he was distributing bills drawn from his own copperplates? As his sitters are formally attired with well-coiffed hair, he was undoubtedly similarly attired and presenting himself as a gentleman. This would be a perfect pretext for him as he could convey himself as a person of social standing and above suspicion whilst he carried on his illicit activities.

Fortunately, these are not the only portraits that can be attributed to “Mr. Willson” and linked to Lyman Parks. Beginning in 1825, a series of stunning portraits, were executed in the state prison in Charlestown, Massachusetts. I made this serendipitous discovery while examining photographs of portraits of Asa Gilmore (Fig. 5) and his brother Addison, from Weston, Vermont, on file at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia. Prior to 1986, when the Gilmore portraits were given to the Weston Historical Society in Weston, Vermont, each panel had a handwritten label adhered to the front citing the sitters’ place and date of birth, and the comment: “Picture painted by inmate of the Charlestown State Prison.” 9 Subsequent perusal of the prison records revealed that Asa, the older brother, was appointed a prison overseer, also known as a turnkey or guard, at that facility in 1826.10

| |

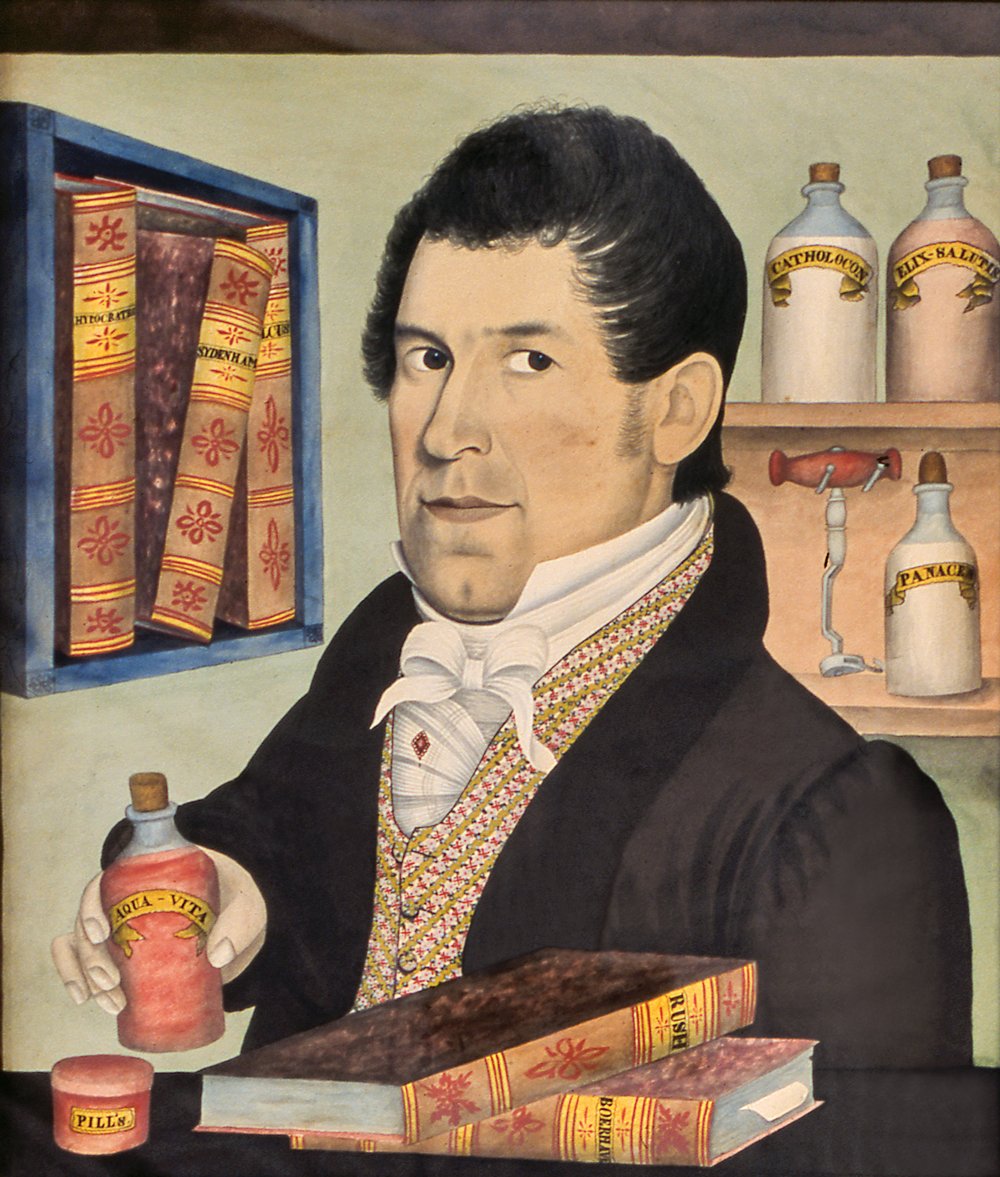

| Fig. 6: Attributed to Lyman Parks (1782-1872), Portrait of Doctor with Books, ca. 1826. Watercolor, 22 x 19 inches. Courtesy of Robert and Katharine Booth; photograph courtesy of Northeast Auctions. |

As I observed at the time, the Gilmore portraits bore all the characteristics present in the watercolors attributed here to Mr. Willson. In 1987, the late folk art scholar Colleen Cowles Heslip had forwarded the Gilmore photographs to the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum after noting they appeared to have been painted by the same hand that painted the AARFAM’s masterpiece, Portrait of Mrs. Seth Wilkinson. In 2011, I attributed twenty panels to the Wilkinson Limner in homage to AARFAM’s Mrs. Seth Wilkinson, but deferred formally linking the Wilkinson Limner to “Mr. Willson” as I was still gathering evidence to support my hypothesis that Lyman Parks aka “James Wilson” was the painter.11

Comparing Asa Gilmore’s oil-on-board portrait here with a watercolor attributed to “Mr. Willson,” Portrait of Doctor with Books (Fig. 6), is revealing.12 Aside from sharing the same pose, they have all the hallmarks of Mr. Willson’s hand and confirm the artist was proficient in both mediums. Nose, mouth, and chin are treated similarly, and hands are rendered in painstaking fashion with a characteristic grayish sheen to the fingernails, and both are fully attentive to the artist who is portraying them. The only real divergence that I have been able to discover in his work is that instead of having all sitters face to the right, after 1825 his male sitters continue to face to the right while female sitters to their left.

The doctor’s features and occupation are wholly consistent with that of Charlestown inmate Dr. Moses Perley Clark, described in the Massachusetts state prison registry as aged forty-three, with dark eyes and dark hair.13 Clark was a physician and a fully trained apothecary who had been caught altering bank bills in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1826. For this, he received a three-year sentence and served his time working in the prison infirmary until his pardon three years later. While in prison, he sat for at least two portraits.14 During the portrait sessions, Clark may well have been teaching his fellow forger how to use various chemicals to alter the denominations and the signatures on real bank notes, providing Parks with additional skills with which to ply his illicit trade.

| |

| Fig. 7: Attributed to Lyman Parks (1782-1872), Portrait of a Man with Key Seated at a Table. Watercolor, 22 x 17 inches. Provenance: Mary Allis; Estate of Austin Palmer, Hopkinton, N.H.; The Bisnoff Collection, Northeast Auctions (Oct. 27 2007, Manchester, N.H.), lot #633. Courtesy collection of William A. Hosie Jr. & Christin A. Couture. |

What is the evidence that Mr. Willson, aka the Wilkinson Limner, was Lyman Parks? Between 1825 and 1827 when Asa Gilmore and Dr. Clark sat for their portraits, Parks was also an inmate at the Massachusetts State prison, serving a two year sentence for counterfeiting bank notes, including one dollar notes issued by the Concord Bank of New Hampshire.15 Although no prison records have survived that specifically cite works by his hand, his sitters, or the prices paid for services rendered during this time, portrait painting was a pursuit clearly condoned by the authorities. Hence Dr. Clark felt free to commission two portraits while incarcerated.16 The fact that Parks had a gift for rendering a likeness and was never idle also fits with the eight portraits he appears to have undertaken during that period.17

That the artist was incarcerated at the time may also explain why the sitter in Portrait of a Man with Key Seated at a Table (Fig. 7) was probably Stephen Bennett. He was one of the principal turnkeys at the prison and was in charge of the east wing of the state hospital where Clark worked. He later provided a character reference for Clark in an alleged breach of marriage contract suit.18

More than a hundred years after Parks was released from the Massachusetts state prison system in 1827, four other portraits that embody all the key characteristics of his hand were found in Philadelphia by Edith Gregory Halpert.19 This is not surprising since Parks had been apprehended in Philadelphia in 1835 for counterfeiting bank notes on the Bank of the United States.20 For this he served four years in the Eastern State Penitentiary there. Since then, more portraits by his hand, either on board or on canvas, have been found, including a handful in New York State where Parks ostensibly spent his later years as the proprietor of a wood-turning business.21

But did Parks actually reform after his release in 1839? This is but one of the key questions that I will be addressing in the forthcoming biography I am writing tentatively titled One Slippery Rogue—Lyman Parks: Artist, Engraver and Counterfeiter.

Deborah M. Child (www.deborahmchild.com) is an independent scholar based in N.H. She is the author of The Sketchbooks of John Samuel Blunt (Portsmouth Athenaeum, 2007), and Soldier, Engraver, Forger: Richard Brunton’s Life on the Fringe in America’s New Republic (New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2015). Should you know of portraits similar to those illustrated here, or of any portraits signed by Lyman Parks, the author would be delighted to hear from you.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. “Lives of the Felons. No. 7. Lyman Parkes alias Wilson the Counterfeiter,” National Police Gazette (New York, N.Y.), vol. 1, no. 20, Jan. 24, 1846, 177–178.

3. National Police Gazette (New York, N.Y.), Sat., Nov. 25, 1848, 2.

4. Parks is not the first counterfeiter to undertake portrait painting. Another counterfeiter/portrait painter was featured in my earlier article in this magazine “Samuel Jordan: Artist, Thief, Villain” (Summer/Autumn 2009, 146–153). Counterfeiter Richard Brunton, the subject of my biography Soldier, Engraver, Forger: Richard Brunton’s Life on the Fringe in America’s New Republic (Boston, MA: NEHG, 2015), painted portraits of the keeper and his wife and child while incarcerated at NewGate prison in East Granby, Conn.

5. New Hampshire Sentinel (Keene, NH), vol. XXV, no.1286, Dec. 5, 1823, 4.

6. Receipt of payment to Wm. Stickney for Colby’s stay, dated June 20 1824, was $5.50 for board and 87 cents for liquor. No monies was charged for horse-keeping or a servant. Box 3, Folder 5, Joseph Colby Jr. Papers, MS2001.114, Cleveland Colby Colgate Archives, Colby-Sawyer College, New London, NH. “A New Line of Stages,” Salem Gazette (Salem, Mass.), Tuesday, Dec. 30, 1823, vol. I, no. 104, p. 3. For further information on travel and taverns in NH see Donna-Belle Garvin & James L. Garvin. On the Road North of Boston (Hanover and London: University Press of New England), 1988.

7. “Portrait, Landscape and Fancy Painting,” New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette (Concord, NH), vol. 1, no. 40, October 5, 1819, 2.

8. Cache located on June 27. New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette (Concord, NH), vol. XVI, no. 797, July 12, 1824, 3.

9. According to museum records at Weston Historical Society, in 1825 when the boys were 22 and 23 years old, their uncle a friend of the prison warden, Thomas Harris, made arrangements for one of the inmates to paint their portrait. Sometime prior to 1986, in order to preserve their painted surfaces, the labels were carefully removed from the Gilmore portraits and filed in the museum records.

10. Massachusetts State Prison, Board of Inspectors Minutes, July 5, 1826, HS9.01/Series 287X, Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass.

11. See Deborah M. Child “Unlocking the Mysteries of the Wilkinson Limner” Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana, vol. 11 (Seattle, WA: Marquand Books in association with Yale University Book Press, 2011), 141–153.

12. According to oral tradition, this work was consigned by a picker who found it in a New Hampshire attic in a box of frames. Sold Northeast Auctions August 8, 2004, lot #1207.

13. Commitment Register 1818–1840, State Prison, Charlestown, Mass., November 15, 1826, entry #841. Microfilm GS-134. Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass.

14. For details concerning Clark’s role at the prison and the portraits he sat for see Moses P. Clark, Inside Out: Or, Judith F. Spofford’s “Refutation” Refuted by “Extracts” of Her Own Selecting (Haverhill, MA, 1830). Collection American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA, pp. 8, 10–14; addendum Note 4-3, 4 & 12.

15. Commitment Register, 1818-1840, State Prison, Charlestown, Mass., entry #696, Microfilm GS-134. Massachusetts State Archives, Dorchester, Mass. Parks was cited as age 37 years [his real age was 43], dark hair and eyes, born Russell, Hampden, Mass. He was admitted April 19, 1825 from Boston and discharged April 29, 1827.

16. Moses P. Clark, Inside Out, addendum Note 4, 3–4. See also “Samuel Jordan: Artist, Thief, Villain” (Summer/Autumn 2009, 146–153).

17. In addition to the two watercolor portraits here of Dr. Clark and the prison guard, I have located six portraits on panel of sitters that have firm ties to the prison in Charlestown, including that of the keeper William Going’s wife and child, a prison guard, the Gilmore brothers and their cousin Jane Dodge.

18. Moses P. Clark, Inside Out, addendum Note 4, 3–4.

19. As recorded in Halpert’s Downtown Gallery records: “Found in Philadelphia.” Series 3: Notebooks: American Folk Art Gallery Notebooks. Oil Paintings, Portraits—Adult Pairs and Family Groups. (Reel 5559, Frames 8–75) http://wwww.aaa.si.edu/collectionsn/collection/downgall.

20. “The United States of America vs. Lyman Parkes alias James Wilson” Spectator (New York, NY) vol. XXXVIII, issue 46, April 27, 1835), 3.

21. Stephen Mihm, A Nation of Counterfeiters. Capitalists, Con Men and the Making of the United States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007, 155.