Freak Pictures? The Needlework Paintings of Margaret Ansell

Winterthur Primerr

New research on a needlework painting recently donated to Winterthur Museum has revealed it to be the work of the English artist and instructor Margaret Ansell, who displayed it at the 1776 Society of Artists exhibition in London. While one early twentieth-century writer described such needlework paintings as “freak pictures,” outside of the realm of art, Ansell’s needlework interpretations of two Benjamin West paintings, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians and The Death of General Wolfe, reveal how female artists participated in the debate over taste and materiality in late-eighteenth-century London.1 Through ambitious interpretations of popular paintings, these women made their voices heard with layers of worsted wool threads.

|

| Fig. 1: Margaret Ansell (n.d.), Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, needlework picture, 1771–1776, Tottenham, Middlesex, England. Worsted wool, silk, linen. Winterthur Museum (2014.0029.005); Gift of Julie and the late Carl M. Lindberg. Photograph by James Schneck. |

| |

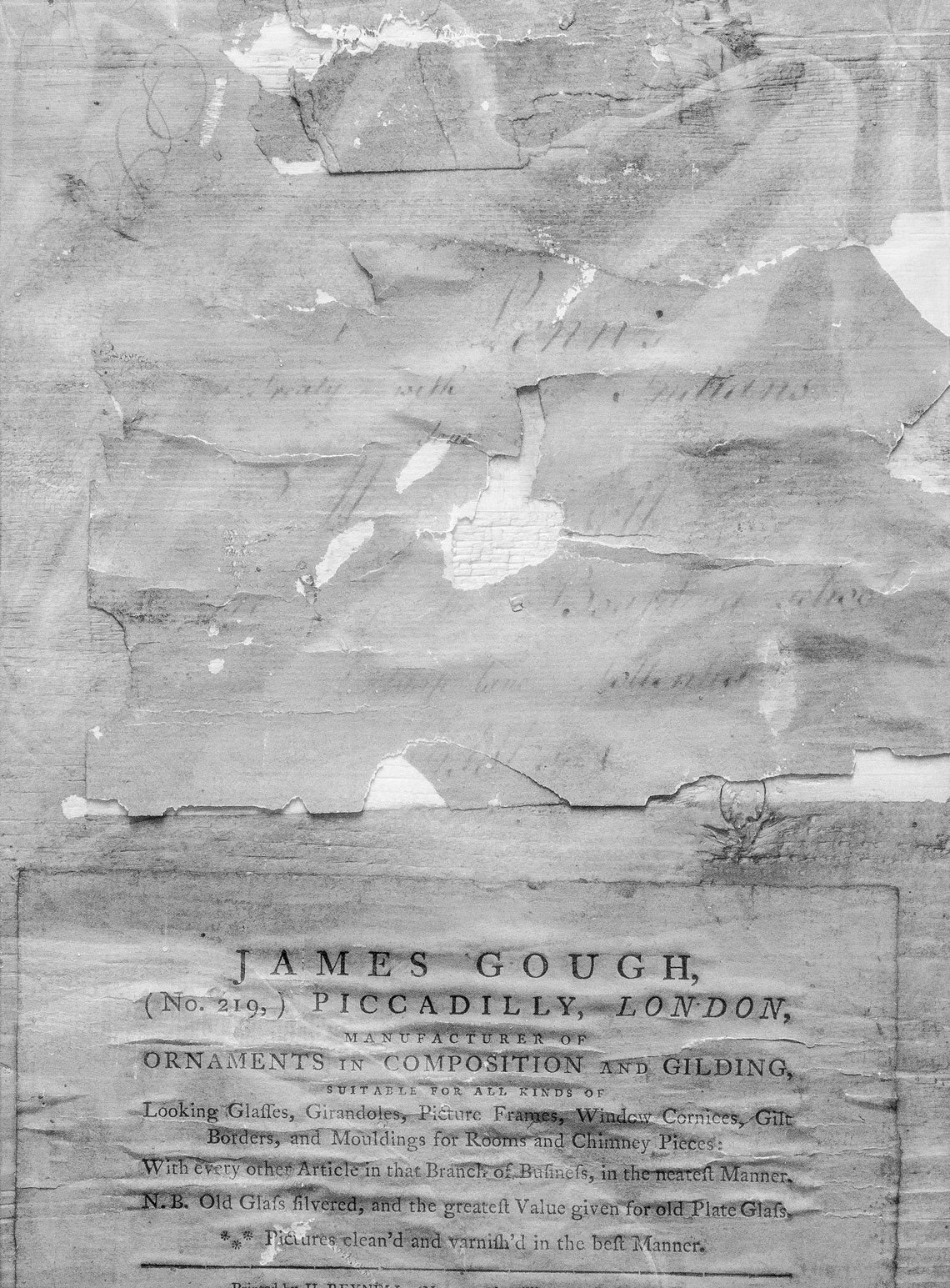

| Fig. 2: Backboard with labels for picture in figure 1. Photograph by James Schneck. |

Winterthur’s needlework picture of Penn’s Treaty is rendered in dense, overlapping stitches of worsted wool yarn by an artist pushing the boundaries of her medium (Fig. 1). Under key figures, she built up the surface, creating a three-dimensional canvas upon which she worked the shades of skin and textiles. Directional stitches animate forms and enhance the illusion of depth. She wrought the initials M. A. in the lower right quadrant of the needlework and attached a now torn label to the back, with the handwritten text “William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians/Done by/M ___sell/ M___ of the Boarding School/ Lordship Lane Tottenham/ Middlesex.” Fortunately, the label of the London framer, James Gough, also remains on the reverse (Fig. 2).

It was the initials M. A. and the James Gough label that brought to light the connection between Winterthur’s needlework painting and an interpretation of Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe in worsted wool, now in the collection of the Deerfield Museum, which shares these features (Fig. 3). The works are also linked by the artist’s technique, including her careful selection of stitches to imitate brushstrokes, the modeling of facial features, and the incorporation of raised elements.

The existence of two identically framed needlework pictures, each based on popular works by West and with the same initials, suggests they were intended for exhibition together. As many exhibition catalogues have been digitized, a search for the pair was quickly rewarded. The 1776 Society of Artists of Great Britain catalogue lists the two as the work of “M. Ansell,” a name that perfectly completes the torn information on the handwritten note, referenced above, which survives on the reverse of the Winterthur example (Fig. 4). Ansell exhibited once more, in 1780, and was referred to as being “at the Boarding School, Tottenham.” A 1782 newspaper notice for the estate of “Miss Margaret Ansell” and the contents of her boarding school in Tottenham further clarifies the artist’s identity.2

|

| Fig. 3: Margaret Ansell (n. d.), The Death of General Wolfe, needlework picture, 1771–1776, Tottenham, Middlesex, England. Worsted wool, silk, canvas. Historic Deerfield collection (HD66.198z). |

Although we do not know a great deal about her career or working practice, subtle details indicate that Margaret Ansell may have studied both of Benjamin West’s original paintings as well as subsequent engravings to accomplish her needlework pictures.3 In size and orientation, Ansell’s interpretation of West’s Wolfe and Penn’s Treaty match the engraved versions. John Hall’s 1775 engraving of Penn’s Treaty flips the original composition while William Woolett’s 1776 Wolfe does not, and Ansell chose to follow the orientation of both prints.4 The degree of correlation between the original colors and the yarns selected, however, indicate a strong familiarity with the painted originals rather than only the engravings.

Light damage has taken an especially hard toll on certain blue and green threads, leaving both works with a decidedly golden cast, but the red has survived well. Small red wool details that relate to Wolfe, including the fringe on the left-most figure’s leggings and the trim on the Native American figure’s robe, correspond perfectly with West’s original painting. The accuracy of the color choices indicates the works could indeed have been rendered in part from in-person examination of West’s paintings, which were displayed at the Royal Academy and remained in London during the engraving process.

| |

| Fig. 4: A Catalogue of the Pictures, Sculptures, Models, Designs in Architecture, Prints, &c. Exhibited by the Royal Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain, London, 1776, page 19, showing the entry for M. Ansell as well as the engraving by William Woollett of Wolfe. |

Margaret Ansell was one of eight artists (all female) who submitted a total of thirteen needlework pictures to the 1776 Society of Artists Exhibition, held at the Society’s Academy on the Strand in London. The eight artists were M. Ansell (Margaret Ansell), Miss Meredith, a “lady at Mrs. Marshall’s Boarding School, Wandsworth,” Miss Secombe, Miss Hinton, Miss Brewer, Mrs. Hannah Linwood, and Miss Mary Linwood. The needlework artists had a rapidly dwindling number of venues that would accept their work, and even the Society of Artists relegated all eight to the “honorary exhibitors” category. The rival Royal Society of Artists explicitly stated in newspaper notices for upcoming exhibitions that “NO COPIES WHATSOEVER, Needlework, artificial Flowers, Models in coloured Wax, or any Imitations of Painting will be received.” 5 Ansell’s use of needlework to copy an existing artwork was the epitome of what the Royal Society sought to exclude. The Society of Artists, however, accepted all of these categories. This divide between the societies represented a broader schism within the artistic community over the composition of the professional trade, and ultimately, what counted as fine art.

The dissolution of the Society of Artists in 1791 did not spell the end of needlework exhibitions, but the context of their display did change in the subsequent decades. The entrepreneurial needlework artist Mary Linwood developed her own independent exhibition that ran for the better part of forty years and became a “must see” in London. Linwood and Ansell were early practitioners of the needlework painting that was widely produced in the early nineteenth century, usually in silk rather than wool. The work of Ansell and Linwood is a transitional form of pictorial embroidery. These artists, and others of their period, utilized worsted wool on linen and a variety of techniques, frequently highlighting forms and imitating brushwork through long, floating, overlapping stitches. The faces rendered by Ansell and Linwood are accomplished fully in embroidery. Needlework pictures of the Neoclassical era that followed tend to use silk on a silk textile and are more likely to employ predominantly shorter stitches. Faces and other minute details are frequently painted, and in some cases, purchased from professional artists. Academies advertised exhibitions of their students’ work in both England and America, while parents patronized professional framers who created églomisé surrounds with text identifying the accomplished student artist. Although no longer permitted on the main stage of professional artistic societies, needlework painting remained an active outlet of expression well into the nineteenth century through academic and domestic sites of display.

The fate of Margaret Ansell is still unclear. A sale of her household and boarding school effects took place in February 1782, which likely indicates she was deceased by this date. Yet there is a hint that Margaret lived on to ply her needle. The final exhibition catalog of the Society of Artists in 1791 includes a “Mrs. R.” whose list of twelve needlework is startlingly similar to those shown by Margaret Ansell over the course of her career. Indeed, a Margaret Ansell (noted as a spinster from Tottenham) married widower James Roberts in 1781. Perhaps the 1782 sale of the “late Miss Ansell’s” property only marked the close of one chapter of her life, but not the end of her participation in the evolving landscape of public art in London.

Lea C. Lane is the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Curatorial Intern at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Formerly, she was the Elizabeth and Robert Owens Curatorial Fellow at Winterthur, where she co-curated the 2016 exhibition Embroidery: The Language of Art.

More Winterthur Primer articles are available by searching Incollect or can be found in one location at Winterthur.org.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (London, England), February 20, 1782. While the 1780 catalogue referred to Ansell as “at the Boarding School, Tottenham,” by 1782, the contents of the school are aligned with her, suggesting that by then she was owner of the school in addition to presumably teaching.

3. The decision of Margaret Ansell to replicate two well-known works by an artist born in the North American colonies, of scenes that took place in North America, at a moment when the relationship between the British North American colonies and motherland were in violent contention, could be read as a political statement, either for the presence of Britain in those areas or for the independent histories of the same. Additionally, both Wests had recently been engraved and would have been familiar to visitors to the 1776 Society of Artists exhibition. The popularity of West’s painting of Wolfe might have influenced Ansell’s decision to interpret this specific composition and to offer it for sale.

4. Ansell exhibited her needlework pictures relatively soon after the engravings were available. In fact, a print of Woollett’s Wolfe was also on display at the 1776 Society of Artists exhibition.

5. There was some inconsistency in the treatment of copies. Engraved versions of both West paintings rendered by Ansell also appear in the 1776 Society of Artists exhibition, but are given full billing (i.e., not honorary exhibitors). An engraving is, after all, often a copy after an existing painting.