At 25: Distinguishing the Biggs Museum of American Art

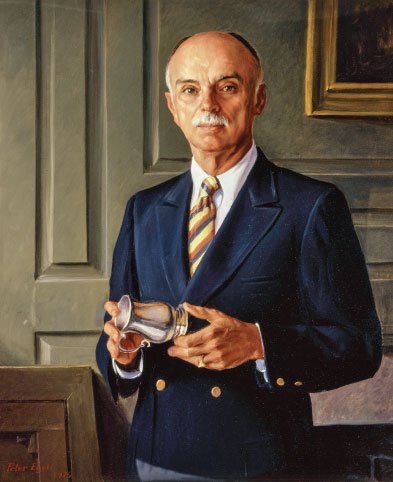

The Biggs Museum of American Art is the only institution working to give national attention to the full range of artistic achievement and cultural strength within Delaware and the Greater Delmarva region. The year 2018 marks the 25th anniversary of the museum’s location on the Delaware state capital’s impressive Legislative Mall (Fig. 1). Since the passing in 1993 of museum founder Sewall C. Biggs, the collection has continued to grow through public sponsorship, private philanthropy, careful choices, and significant good fortune.

|  | |

| Fig. 1: The façade of the Biggs Museum of American Art, featuring its first permanent sculptural installation, Aloft (2015), by Erica Loustau, the capstone of the museum’s 2011–2014 renovation. | Fig. 2: Peter Egeli (b. 1934), Sewell C. Biggs, 1979. Oil on canvas, 43¼ x 37½ inches. Bequest of Sewell C. Biggs (2004.469). |

|

| Fig. 3: The Marcia and Henry DeWitt Gallery, the Biggs Museum of American Art, as it appeared in 2015 after the museum’s three-year renovation. Featured are works by the family of Charles Willson Peale and Federal Delaware furnishings. |

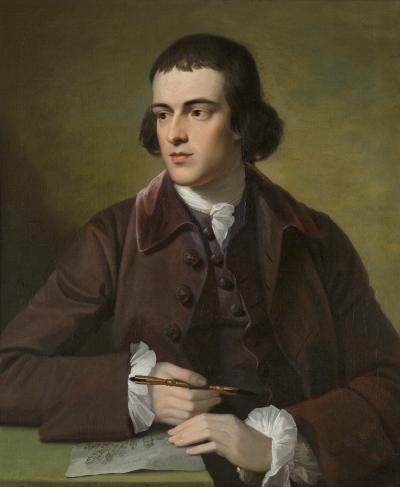

After sixty plus years of collecting, Sewell C. Biggs (Fig. 2) left behind an institution rich in early mid-Atlantic furniture, especially from Philadelphia and Delaware, and portraiture by regional limners of the period before 1825. He collected exceptional local colonial silver and works by members of the Charles Willson Peale family of artists. Reportedly urged by the collector Lee B. Anderson to acquire nineteenth-century American landscape paintings and sculpture, Biggs also found a niche within the regional collections of Brandywine illustrators, acquiring a large selection of works by Frank E. Schoonover (1877–1972), and significant examples by notable American impressionist and postimpressionist painters. Biggs pieced together a collection that demonstrated the history of many major movements in American representational painting through the early twentieth century peppered with objects representing the local Delaware flavor of these periods.

| |

| Fig. 4: The Delaware Silver Study Center, the Biggs Museum of American Art, featuring the Col. Kenneth P. and Regina I. Brown Collection. |

After 2003, the staff and trustees of the museum initiated several ambitious exhibitions, programs, and capital campaigns to induce greater attention and support from the community. The hiring of my position as museum curator culminated in a three-year expansion and renovation of its galleries (Fig. 3), several ground-breaking publications, educational partnerships, and widening public participation. Perhaps most notably, the museum’s permanent collection has doubled in size. Part of this growth came in the form of an important partial gift of the Colonel Kenneth P. and Regina I. Brown collection of Delaware silver (Fig. 4), As the most important single gift to the museum since the passing of its founder, the Brown Collection is a near encyclopedic collection of work by Delaware silversmiths and retailers until 1900.

The museum strives to refine and enlarge the foundational strengths of the original Biggs collection (Fig. 5). In 1992, Biggs purchased at auction Charles Willson Peale’s portrait of Maskell Ewing (1788), seen on the left, as a centerpiece to his grouping of paintings by Peale family members. In 2016, the museum was able to purchase the companion of this wedding set, the portrait of Jane Hunter Ewing; both retain their original frames. The two were reunited at the museum on Valentine’s Day.

|

| Fig. 5: Charles Wilson Peale (1741–1827), Portrait of Maskel Ewing and Portrait of Jane Hunter Ewing, 1788. Oil on canvas, each 41¾ x 32⅝ inches. Bequest of Sewell C. Biggs & museum purchase (2004.438 & 2016.2); Tall clock, after 1774, by James Kinkead (working in Philadelphia and Chester County 1760–1774 and in Christiana Bridge starting in 1774, perhaps died in 1797), Christiana Bridge, Del. Mahogany, brass. Museum purchase (2008.31); Two of five side chairs, 1795, by John Janvier (1749-1801), Cantwell’s Bridge (Odessa), Del. Mahogany. Gift of Barbara L. Simons (2011.11.1-.5). Photo by Andrew Dalton. |

|

| Fig. 6: Four side chairs, 1740–65, maker unknown, Dover, Del. Walnut. Gift and partial gift of the Loockerman/Bradford Family (2013.10.1-.2); Pembroke table, 1760–80, perhaps Benjamin Randolph (1721–1791), Philadelphia, Pa. Mahogany. Museum purchase (2006.17); Mary Tobias Putman (b. 1943), A Map of the World, 2006. Acrylic on panel, 46½ x 111½ inches. Museum purchase (2010.7). Photo by Andrew Dalton. |

| |

| Fig. 7: Michael Robear (b. 1962), Untethered, 2009. Watercolor on paper, 32½ x 44¼ inches. Gift of the artist; Wainscot chair, 1720–50, maker unknown, Cecil County, Md. Walnut. Museum purchase (2015.5). Photo by Andrew Dalton. |

Shortly after the publication of the Biggs Museum’s seminal study of Delaware tall-case clocks, its staff located an example, shown in the center of illustration five, by James Kinkead. Not as well known as other early-Delaware clockmakers already within the museum’s collection, this example has perhaps the most sophisticated engraved decoration of any Delaware clock known. Kinkead inscribed the silvered clock face with his name and “Christiana Bridge,” the place where his family had lived and operated a clock-making business perhaps since before 1750.1 The Biggs legacy was further enlarged with the gift of five side chairs, a pair of which is shown in figure 5. Originally from a set of twelve, of which only the Biggs five are known to have survived, these chairs are the only documented examples made by the famed Delaware cabinetmaker, John Janvier (1749-1801). Recorded in two separate copies of a 1795 receipt made out to Thomas Hardcastle of Castle Hall in Queen Anne’s County, Maryland,2 Janvier’s chairs populate a gallery within the museum dedicated to his work and influence upon the next two generations of cabinetmakers within the state.

While the museum continues to celebrate Mr. Biggs’ passion for early-Delaware furniture by exclusively adding well-documented and signed examples to his collection, few are as prized as the four 1740–65 compass-seat side chairs made for the Dover home of wealthy merchant Vincent Loockerman (Fig. 6)3 They complement the contemporaneous set of trapezoid-seat chairs and dressing table collected by Biggs (not illustrated), and are among the earliest known furniture believed to have been made in Delaware. The museum purchased the Pembroke table, also seen in figure 6, which may have been made by Benjamin Randolph (1721—1791), who supplied chairs to Loockerman, presumably in the 1760s.4

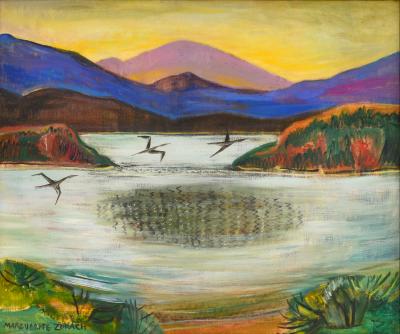

The respect paid to Sewell C. Biggs’ interests in the growth of the museum’s collection is also matched by an equally ambitious desire to forge new directions and to illuminate new relationships within the museum’s galleries. The modern and contemporary art collections are among the fastest growing portions of the Biggs Museum. As examples of national trends of the past hundred years are added to expand Mr. Biggs’ collection, much of the most exciting work being collected was made within the Mid-Atlantic region, and especially Delaware. Juxtaposed above this treasure of Loockerman material seen in figure 6, is A Map of the World (2006) by Townsend, Delaware, resident Mary Tobias Putman, winner of the Hassam, Speicher, Betts & Symons Purchase Fund Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This minimalist landscape pictures the timeless fishing village of Leipsic on the Delaware Bay only a few miles from the Biggs Museum.

|  | |

| Fig. 8: Robert Feke (1701-1751), Tench Francis, ca. 1740. Oil on canvas, each 43 x 36 inches. Museum purchase (2015.2.1). | Fig. 9: Ethel Pennewill Brown Leach (1878–1959), Far View, before 1926. Oil on canvas, 29½ x 62¼ inches. Museum purchase (2010.6); Sideboard, 1914, by Don Stephens (1887–1971). Oak, iron. Gift of the estate of Caroline Stephens Holt (2011.1.1). Photo by Andrew Dalton. |

The juxtaposition of periods is evident in other displays as well (Fig. 7). The museum has enjoyed tremendous success in looking to the nearby areas of the Chesapeake and southeast Pennsylvania to find relevant and related objects such as the wainscot chair dating from 1720–50, and documented to the Samuel England family of Cecil County, Maryland, a few miles outside Newark, Delaware. With a dearth of known early Delaware-made examples, the chair represents the type of furniture that would have been made and used within the state. Maryland has also provided contemporary points of view that dovetail perfectly with the region’s best-known artistic legacies. Michael Robear of Cecil County, Maryland, created Untethered (2009), in response to the death of Andrew Wyeth, a life-long influence in his surreal aesthetic formulated at the Corcoran School of Art (fig. 7).

The Biggs Museum recently purchased at auction the portraits of Tench and Elizabeth Turbutt Francis (ca. 1740) by Robert Feke ( ca. 1705 or 1707–ca. 1752) (Fig. 8). Now the earliest portraits within the collection, the couple lived in Kent County, Maryland, just miles from Dover, in the service of Lord Baltimore until relocating to Philadelphia in the 1740s. Through new partnerships, the museum has added an entire new gallery in recent years, with several examples of artworks created in the state’s two artist colonies: Arden, established north of Wilmington in 1900, and the Rehoboth Art League, opened in 1938 in Sussex County. The over-mantel coastal scene entitled Far View (Fig. 9) is by Ethel Pennewill Brown Leach (1878–1960), a student of Howard Pyle and co-founder of the Rehoboth Art League. The work is among the largest and most ambitious of Leach’s paintings of the lighthouse at Cape Henlopen, which fell into the ocean in 1926. Below it is a Mission-style sideboard that is part of a dining room created by the son of Arden founder, Frank Stephens, for his brother’s 1914 wedding. Woodworking was one of several arts-and-crafts industries that flourished in Arden’s utopian society. Others included the Arden forge that created the sideboard’s medieval-inspired hardware.

|  | |

| Fig. 10: William D. White (1896–1971), The Night Shift on Broad Street, ca. 1926. Oil on canvas, ca. 38 x 32 inches. Promised gift of Nancy Carol Willis. | Fig. 11: Edward Loper (1916–2011), Mae Mafco, ca. 1940. Oil on canvas, 37½ x 22 inches. Museum purchase (2007.4); Side table, 1865–1900, by “Big Tom” Burton (n.d.), Long Neck, Sussex County, Del. Walnut, unidentified root. Museum purchase (2009.4). Photo by Andrew Dalton. |

Always a great advocate of American illustration, the museum features one of the largest collections of the works of Frank E. Schoonover, as previously noted; the collection has recently expanded to include work by newly discovered figures, including works by the enigmatic William D. White (1896–1971). The Night Shift on Broad Street (Fig. 10), is the artist’s masterpiece. An illustration for a Hercules Corporation trade magazine, the image represents one of the earliest paintings in Delaware to incorporate realist subject matter of the working classes and people of color. Surprisingly, the artist’s socially conscious images graced the pages of a publication designed to increase sales of industrial chemicals.

The recognition of gaps in the museum’s collections have prompted the design of a lecture series by outside scholars to highlight new opportunities for the museum from populations of color, religious groups, visitors of different abilities, women, and the LGBTQ community. Among a few early examples of these new directions is a small table that dates to the last quarter of the nineteenth century (Fig. 11). According to family tradition, the table was created by an African American sharecropper named “Big Tom” Burton who farmed on the Burton Plantation in Sussex County, Delaware. The painting above it, Mae Mafco (ca. 1940), was painted by Edward Loper (1916–2011), an African-American modernist who started his career as an illustrator in Wilmington for the Index of American Design during the Great Depression. He later studied aesthetics at the Barnes Foundation and received an honorary doctorate for his artistic accomplishments.

In its first ten years, Mr. Biggs opened and nurtured a small American art museum with a teaching collection that reflected important early artforms of Delaware. In its next 15 years, the museum’s staff and trustees cultivated his foundation to build one of the finest regional art museums in the country. An exhibition celebrating the museum, At 25: Distinguishing the Biggs Museum of American Art, will feature the new accessions illustrating this article and debuting the museum’s new acquisition, a recently conserved Robert Henri oil sketch. The exhibition will be on view during the 54th Annual Delaware Antiques Show in Wilmington, Del., from November 10-12, 2017.

Ryan Grover is curator of the Biggs Museum of American Art, Dover, Delaware.

A Collector’s Perspective on the Biggs Museum

Thanks to the keen eye of its collector and founder, Sewell C. Biggs, the Biggs Museum of American Art, in Dover, Delaware, has a remarkable and varied collection that includes paintings, furniture, and decorative arts. One of the most impressive works in the Biggs collection is a stunning painting by Philadelphia artist, George Robert Bonfield (1805–1898), entitled Summer on the Delaware (1850).

|

| George Robert Bonfield (1805–1898), Summer on the Delaware, 1850. Oil on canvas. Biggs Museum of Art. Sewell C. Biggs bequest (204.443). |

What I admire about Bonfield’s work is that he experimented with the abstract possibilities of color and form in the seascape. Bonfield’s composition shows a particular allegiance to the art of Thomas Birch (1779–1851). His approach to his marine paintings display less interest in topographical detail than the works of his contemporaries. He had a lifelong fascination for tall ships and the sea (as indicated by his childhood sketches drawn in his schoolbooks), and his ships move, his seas are alive, and his sails form sweeping arcs. Bonfield’s marine paintings reveal a decided Dutch influence of contrasting light and dark to dramatize his prominent subjects. His brushwork is not that of a draftsman but of a Romantic with a loose flowing application. Depth and perspective are achieved by low horizons under large skies of billowing clouds, so that the feeling conveyed to the viewer is of an artist who knew his subject well and could translate that knowledge into a strong expression.

My own collection of marine art began at an early age, when, as one born “under a water sign,” I was attracted to marine art in museums. I so admired Bonfield’s works that I began to collect them where I could and now own several, among other American marine artists. During the nineteenth century, Bonfield, like another artist of the period, such as James Hamilton (born Ireland,1819, died San Francisco,1878), enjoyed attention from collectors and galleries, but public tastes changed in the twentieth century and their work lost favor. Another reason I enjoy the Biggs Museum is that its collection contains the works of both of these artists.

— James McClelland

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Both copies of the receipt are at the Biggs Museum of American Art. The original receipt is currently unaccounted for within the family who donated the chairs.

3. Two chairs have been gifted and two are currently promised gifts of the descendants of Vincent Loockerman.

4. The Biggs Museum owns one side chair of this set, inscribed with Randolph’s name and the partially obscured date of 1762 or 1765.