Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern

The genesis of my book and exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern unfolded over some twenty years. It derived from two experiences: first, my earlier scholarship on the artist and second, my lifelong curiosity about what might be learned from an artist’s material culture — her home, her studio, her furniture, and her clothing.

Like many of my generation, I became aware of Georgia O’Keeffe’s (1887–1986) art in 1970 when I saw her first major New York museum retrospective at the Whitney Museum. In 1980, I interviewed O’Keeffe in her home in the fairly remote village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, a visit that gave me my first inkling that she was an artist not only in the studio but in the making of her homes and self-fashioning. Subsequently I learned that when O’Keeffe died in 1986, the closets in her two New Mexico homes were filled with garments. What light, I wondered, might this material shed on an already much-studied and famous artist? Some of her clothes were exquisitely handmade or professionally tailored; most were black and white, but in New Mexico she had introduced colors like blue and red into her wardrobe. I wasn’t free to pursue these questions until 2013 when, recently retired, I received a research fellowship at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum to study the artist’s wardrobe. The research I undertook with Susan Ward, an historian of textiles and fashion, and Carolyn Kastner, curator at the O’Keeffe Museum, became the subject of a book and exhibition, titled Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, that opened at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017 and is currently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The exhibition, retitled Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style features sixty items from her wardrobe. These are the stars of the exhibition, but they are given context and deeper meaning by forty pieces of O’Keeffe’s art and seventy-three photographs depicting the artist, her home, and domestic life—evidence that O’Keeffe upheld the same aesthetic of simplicity and minimalism in her self-fashioning and homes as she did in her work. With the help of her husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, she used her clothed body to build a public identity. After Stieglitz died, other photographers continued the task. She modeled for over forty photographers and consistently dressed for her portraits in the two colors she savored: black and white.

Here is a sampling of the exhibition’s highlights, with texts drawn from captions that accompanied them. Rejecting the staid Victorian world into which she was born, O’Keeffe absorbed the progressive principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, which promoted the idea that everything a person made or chose to live with — art, clothing, home décor — should reflect a unified and visually pleasing aesthetic. Even the smallest acts of daily life, she liked to say, should be done beautifully, a philosophy reinforced by her study and appreciation for the arts and cultures of Japan and China.

O’Keeffe applied these principles to her lifestyle comprehensively. The elemental, abstracted forms and serial investigations that characterized her art were also evident in her clothing. Whether hand sewn by her, custom made, or bought off the rack, her garments and the way she styled them emphasized her preference for compact shapes, simple lines, organic silhouettes, and minimal ornamentation. The many photographic portraits made of O’Keeffe over the course of her life reveal how carefully she dressed and posed for the camera, and how the photographer’s gaze so often bore witness to the deliberate alliance between the artist’s attire, her art, and her homes. For O’Keeffe, photography played an essential role in shaping and promoting her public identity and helped establish her present-day status — enduring, but to her, unintentional — as an icon of feminism and fashion.

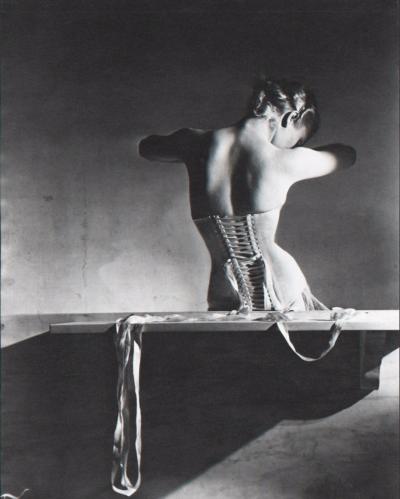

| Dress (tunic and underdress), attributed to Georgia O’Keeffe, ca. 1926. Ivory silk crepe. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton (2000.03.0235 and 2000.03.0236). Photo © Gavin Ashworth. O’Keeffe was an accomplished seamstress who hand made her clothes early in her life. Because of its fine details and high-quality construction — hallmarks of her dress in the 1920s — it seems reasonable to assume that she made this ivory silk ensemble. That she moved this garment and others like it from one home to the next for over half a century, suggests that they carried memories not only of her first years with Stieglitz but also of her considerable labors and artistry in crafting them. Tunics worn over an underdress of the same fabric were popular in both fashion and “art dress” in the 1920s, especially among artists and habitués of Greenwich Village. Peasant sleeves inspired by traditional Russian and Balkan vernacular dress were also trendy. O’Keeffe’s design conformed to her desire for ease of movement and evidence the ways she distilled and personalized current fashions. |  |

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Line and Curve, 1927. Oil on canvas, 32 x 16¼ in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Alfred Stieglitz Collection, Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe (1987.58.6). © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. O’Keeffe enjoyed painting entire pictures in shades of black and white, the same restricted palette she used in dress. First in her abstract drawings and watercolors in the 1910s, then in oil paintings of the 1920s, she made black and white into “colors” that were subtle and versatile. Sometimes she juxtaposed them; she also mixed the two and came up with a beautiful tonal range of grays. This narrow, vertical abstraction may also have been informed by O’Keeffe’s paintings of modern skyscrapers of Manhattan in the late 1920s. |

|

| Installation view at the Brooklyn Museum showing blouses and Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Yellow Leaves (Yellow Leaves), 1928. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30⅛ in. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe (87.136.6). Photo by Jonathan Dorado. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. © 2017 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

|

.jpg) | Detail, blouse, attributed to Georgia O’Keeffe, circa early to mid-1930s. White linen. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton (2000.03.0248). Photo © Gavin Ashworth. The decoration at the center of this handmade blouse offers a lovely companion to O’Keeffe’s paintings of crinkly-edged autumn leaves and corrugated seashells. The blouse and its ornament are shaped by tiny pintucks that look like the veins of a leaf. A conscientious mender of clothes she liked to wear, O’Keeffe meticulously patched the back of this blouse. |

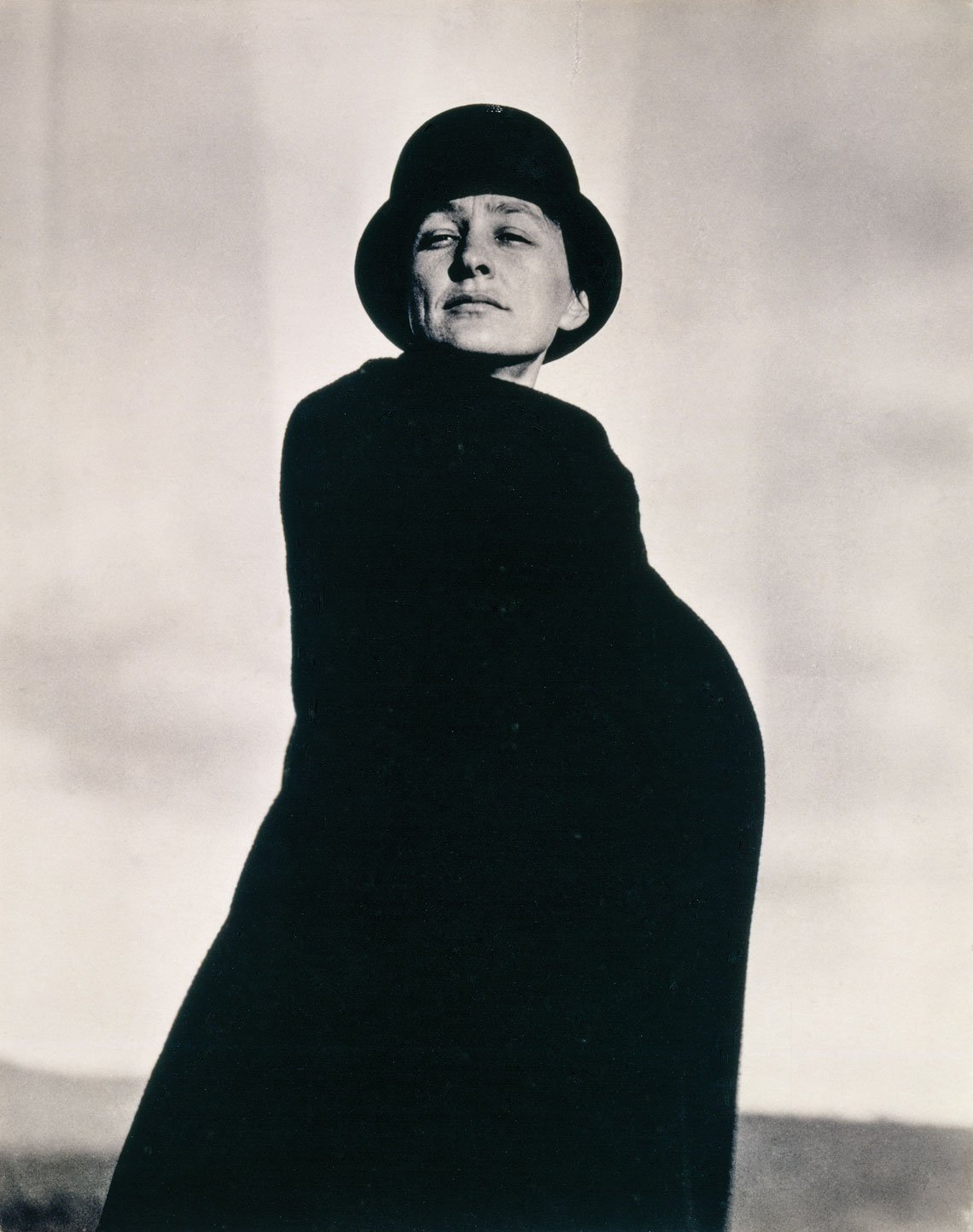

| Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), Georgia O’Keeffe, 1920–22. Gelatin silver print. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (2003.1.6). Photo © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. O’Keeffe treated her head and body like a blank canvas — something to be covered in abstract shapes. Like other radical women in the 1920s, she also experimented with gender-bending clothing to challenge and confound society’s conventional sartorial codes for men and women. For this photo session, O’Keeffe wore a bowler-like black hat and wrapped herself in Stieglitz’s cape, hiding its prominent buttons and collar. Sensitive to her daring androgyny, Stieglitz photographed her from a low vantage point, highlighting her streamlined body and emphasizing the way her clothing crossed gender lines to be neither male nor female, or both. |  |

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Manhattan, 1932. Oil on canvas, 84⅜ x 48¼ in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (1995.3.1). Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C./Art Resource, NY. In 1932, for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, some sixty contemporary artists were commissioned to create designs for a large public mural. Each was asked to submit a small mock-up of a mural and then scale up one part of the design. O’Keeffe’s mock-up was a triptych of modern New York cityscapes, claiming for herself a subject that had long been the province of male artists. This painting is her enlarged version of one piece of her overall design. It is a colorful composition of pink, mauve, red, black, and white skyscrapers, two wedges of blue sky, and, as her personal signature, three floating flowers. |

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Brooklyn Bridge, 1949. Oil on Masonite, 48 x 35⅛ inches. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Mary Childs Draper (77.11). Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. © 2017 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. When Stieglitz died in 1946, O’Keeffe made plans to move to northern New Mexico where she had been spending summers. In 1949, about to leave, she painted this farewell salute to New York, her home for thirty years. The Brooklyn Bridge was an iconic subject for her generation of modern artists, but she had never painted it before. She used the twin arches and harp-like cables of the bridge to create a valentine to the things she was leaving behind, saying goodbye to Stieglitz, their partnership, and the city where they launched their careers. The bridge is also a gateway, perhaps her metaphor for leaving the manmade city of stone and steel for the clear blue skies of New Mexico. |  |

|

| Installation view at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Jonathan Dorado. Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. Above left: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), In the Patio IX, ca. 1964. Oil on canvas mounted on panel. The Jan T. and Marica Vilcek Collection; Promised gift to The Vilcek Foundation (2012.05.01). Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. © 2017 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Above center: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Glen Canyon, ca. 1964. Polaroids. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation (2006.6.1084; 2006.6.1086; 2006.6.1092). Courtesy Brooklyn Museum. © 2017 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

|

| Emilio Pucci (1913–1992), “Chute” dress, ca. 1954. Black and white cotton. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton (2000.03.0614). Photo © Gavin Ashworth. The ‘V’ shape was prominent in O’Keeffe’s aesthetic. It occurs here in this abstract painting inspired by her beloved patio at Abiquiu. Her attraction to this simple geometric shape is also evident in the adjacent series of Polaroids she took at Glen Canyon while on a rafting trip on the Colorado River in 1961. She was captivated by the natural V created by the dark rock formations against the bright sky, and took a series of pictures capturing that slice of landscape under different light conditions. O’Keeffe’s 1954 “Chute” dress was one of the first Pucci dresses to be sold in the American market, testifying to O’Keeffe’s interest in and awareness of contemporary fashion. It was also a dress that featured pure geometric forms at a time when O’Keeffe was returning to abstraction in paintings. The waistless dress flared like a “chute” (or parachute), with the black shapes pieced together to extend without interruption from the shoulders to the hem. The design incorporates O’Keeffe’s signature V-neckline and convenient side pockets, a feature she invariably incorporated in her dresses. When this garment was catalogued, hankies were found in its pockets and pin marks at the V-neck, suggesting she wore it with her Calder or Navajo button pins. |  |

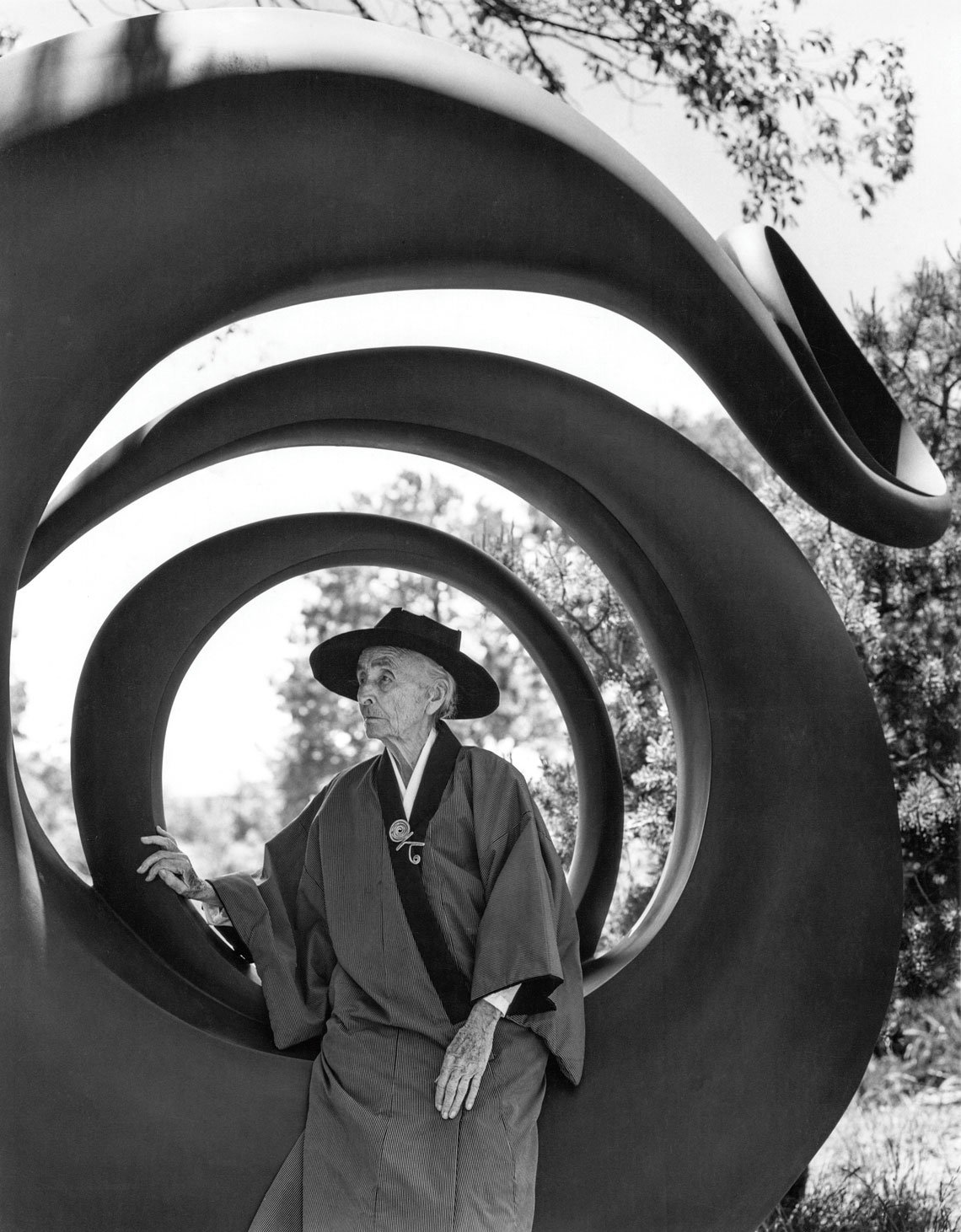

| Padded kimono (Tanzen), ca. 1960s–70s. Gray striped silk, black silk faille, cotton. Inner garment: Kimono, white linen. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton (2000.03.0359). Photo © Gavin Ashworth. O’Keeffe acquired many kimonos, buying her first ones in the 1910s, when she could find them in New York’s many emporia of imported Asian goods. Some were fashioned for the Western trade, some for domestic Japanese use. She may have also made one or two; commercial patterns for kimonos were readily available and their basic T-shape made them relatively easy to sew. When O’Keeffe traveled to Asia she also bought kimonos, and in the late 1970s and 1980s she purchased others from a store in Santa Fe. She had women’s and men’s styles and wore them in the Western manner, pulling them together with matching belts and narrow sashes rather than the traditional obi. She also overlapped the right side over the left side, rather than the other way around as the Japanese traditionally do. |

| Bruce Weber (b. 1946), Georgia O’Keeffe, Abiquiu, New Mexico, 1984. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 inches. Courtesy of Bruce Weber and Nan Bush Collection, NY. © Bruce Weber. O’Keeffe considered kimonos intimate wear and did not wear them when modeling for photographers. She made one major exception late in life when she wore this kimono for Bruce Weber’s camera. The prominent fashion photographer made portraits of O’Keeffe on two different occasions. For his first visit in 1980, she posed as she had been doing for twenty years, in a black wrap dress, seated against bones and firewood at Ghost Ranch. For the second sitting in 1984, the ninety-seven-year-old artist came up with a hybrid outfit fusing male with female and East with West. She wore a heavy Japanese men’s padded winter robe and her well-worn vaquero hat, with something white to emphasize the V-neck, and her Alexander Calder pin to hold the front together. Framed within the calligraphic circles of her own abstract sculpture, O’Keeffe looks away, a dignified, seemingly genderless elder. This inwardness was truly there in O’Keeffe’s aging body. Macular degeneration made it impossible for her to read or make art, and she now lived for many hours of the day in her mind, sitting quietly with her eyes downcast, listening to music or caretakers reading to her. This is the last formal portrait anyone made of O’Keeffe. |  |

Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style is organized by the Brooklyn Museum with guest curator Wanda M. Corn. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated, 320-page catalog written by Wanda M. Corn. The Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, is the third venue for this nationally touring exhibition, on view through April 1, 2018. For more information, visit www.pem.org or call 866.745.1876.

Wanda M. Corn, Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor Emerita in Art History at Stanford University, retired from teaching in 2007 and continues to research and organize major museum exhibitions. She advocates for the significance, preservation, and interpretation of places where artists have lived, labored, and left material remains.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.