The recently published The Art of the Peales presents the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s unparalleled body of work by America’s first artistic dynasty. Thanks to Robert L. McNeil Jr.’s gift of his personal collection,1 the museum, which previously possessed a fine but small group of works, now contains over 150 works by fifteen different artists in the family of Charles Willson Peale. The largest, most diverse collection of their art, created between the early 1770s and the early twentieth century, it encompasses watercolor on ivory miniatures, oil portraits, landscapes and still life in oil, and prints, drawings, and cut paper profiles. It also contains a wide variety of Peale family portraits, of which The Staircase Group is the most well-known.

The scope of this collection, which includes the work of six female artists, provides an opportunity to explore the dynamics of artistic influence and illuminate how the Peales responded to one another’s work by selectively borrowing, adapting, or replicating forms, techniques, and entire compositions. These interactions were motivated by a desire to master artistic skills, to assist a parent or sibling in completing commissions, or to derive financial benefit by meeting an established demand for a type of work made popular by another family member. In the process, the Peales maintained their affinities to one another while developing their individual areas of expertise. Examples of these interactions are illustrated by the ways in which James Peale’s daughters Margaretta and Sarah Miriam, as well as their cousin, Rubens, and his daughter, Mary Jane, adapted the still life pictures of James and Raphaelle, who had brilliantly reinvented European still life forms for an American audience. Also, notable are the examples of portraiture that illustrate the impact of Rembrandt Peale’s methods on the work of his cousin Sarah Miriam and his niece Mary Jane, as well as the way in which his finely crafted realistic portraiture informed the late style of his father, Charles Willson Peale.

Peale learned to fulfill the desires of the elite patrons of his native Maryland, and those of Virginia and Pennsylvania, by mastering the art of grand manner portraiture in Benjamin West’s London studio between 1767and1769. This portrait of John and Elizabeth Cadwalader and their daughter is the centerpiece of a rare ensemble of five family portraits, commissioned by Cadwalader for his grand Philadelphia townhouse, exemplifying Peale’s success. Charles’ detailed rendering of Elizabeth’s impressive jewelry and clothing is set within an intimate composition reflecting the latest trend in British portraiture. His use of William Hogarth’s (1697–1764) serpentine “line of beauty,” as his central design element, enlivened his figures and their handsome furniture. Cadwalader became a distinguished general during the Revolution and Peale’s commanding officer at the Battle of Princeton. The other Cadwalader family portraits and the card table seen in the picture are also in the museum’s collection.

|

|  |

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Portrait of John and Elizabeth Lloyd Cadwalader and Their Daughter Anne (1742–86; 1742–76; 1771–1850), 1772. Signed and dated, beneath table: C.W. Peale/pinx 1772. Oil on canvas, 50½ x 41¼ inches. Purchased for the Cadwalader Collection with funds contributed by the Mabel Pew Myrin Trust and the gift of an anonymous donor (1983-90-3).

|

|

|

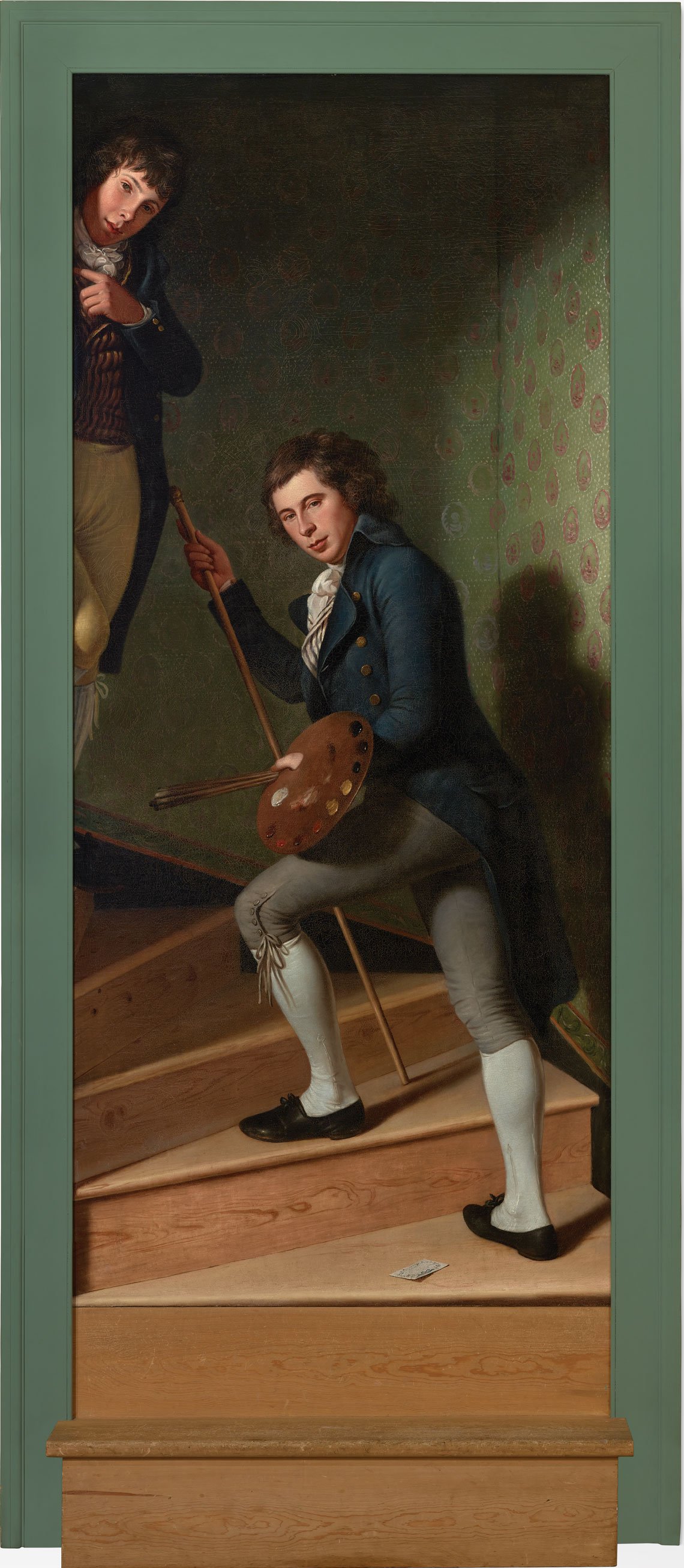

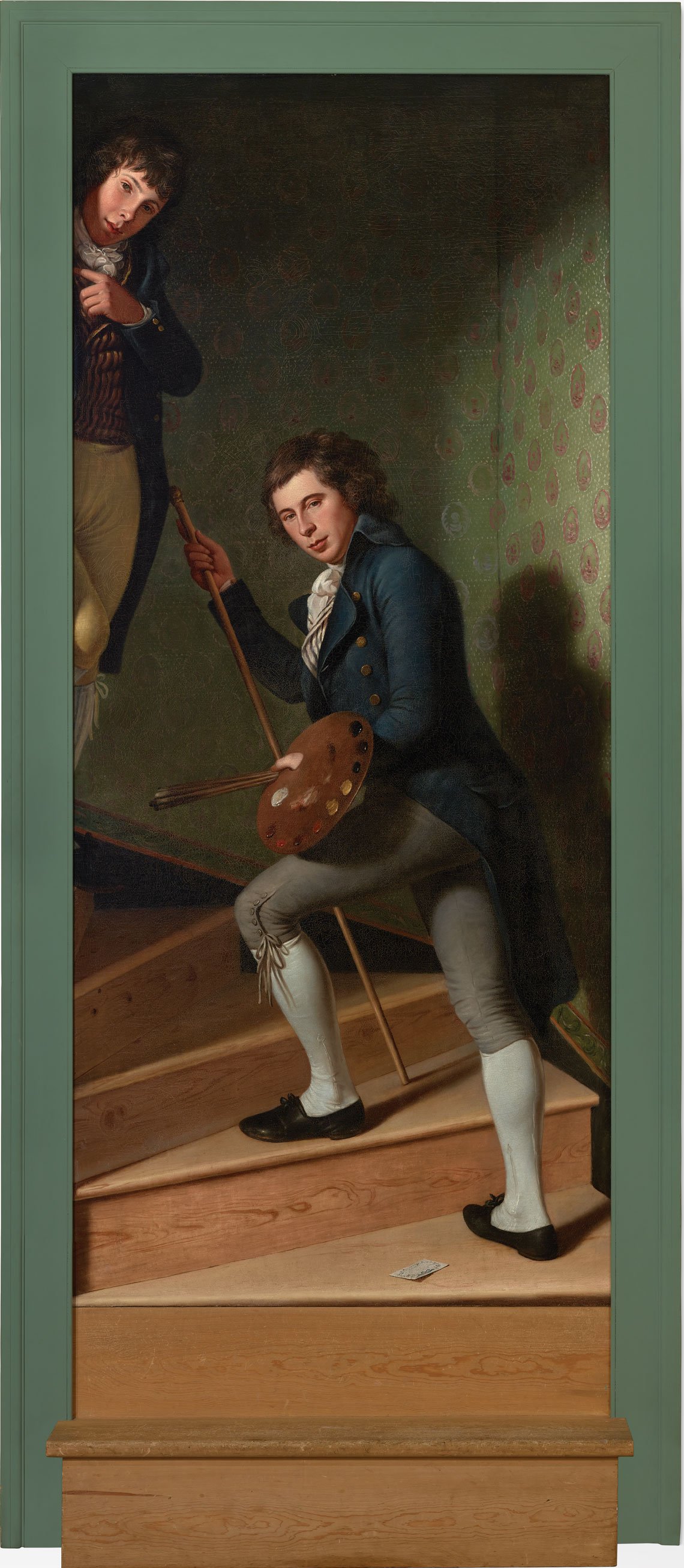

| In May 1795, at the inaugural exhibition of the Columbianum, America’s first, although short-lived, art academy, Charles Willson Peale exhibited his skill in rendering a full-length figure in motion and his mastery of pictorial illusionism with this portrait of two of his sons, Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay, on a staircase. Shortly thereafter, Peale installed the picture in his museum, the first successful American museum open to the public. Here the portrait asserted the literal presence and participation of his sons as part of the museum’s mission to share useful knowledge and entertain through its displays of art and natural science, which were the young men’s individual areas of expertise. Charles envisioned his sons as part of a talented rising generation that would distinguish the new nation and bring success and respect to his family.

|

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), The Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay Peale (1774–1825; 1780–98), 1795. Oil on canvas, 89½ x 39⅜ inches. The George W. Elkins Collection (E1945-1-1).

|

|

Charles Peale Polk, the orphaned son of Charles Willson Peale’s sister, Elizabeth Digby Peale (1747–1776) and her husband Robert Polk (1744–1777) was given a home and painting lessons by his uncle. Polk’s early style closely followed Charles’, and he found a ready market for his smaller scale versions of Peale’s 1787 life portrait of Washington. Active in Baltimore, western Maryland, and northern Virginia, his success in a more rural context may have contributed to the development of his later bolder, simplified style that gave full reign to his delight in color and pattern. The composition of his portrait of John Hart was one often used by Charles in the 1770s and 1780s, and the sitter’s tight, rosy lips reflect a Peale family anatomical formula. Yet Polk crafts his own crisp, individualized likeness with his description of Hart’s long nose, slightly knitted brow, and dark curling hair.

|

|  |

Charles Peale Polk (1767–1822), Mr. John Hart, ca. 1798. Oil on canvas, 37½ x 33⅝ inches. Collection of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch (1968-222-1).

|

|

|

James Peale (1749–1831), Apples and Grapes in a Pierced Bowl, 1823–25. Oil on canvas, 15 x 21¾ inches. Promised gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (x-8299).

|

|

James was instructed in the art of painting by his brother Charles and assisted him in his painting rooms in Annapolis and Philadelphia before launching his own career. A gifted portraitist in watercolor on ivory miniatures and in oils, he painted landscapes and small-scale historical scenes and excelled in still life painting. Along with his nephew, Raphaelle, he is acknowledged as a founder of the American still life tradition. Like most Peale family still-life pictures, this composition is presented on a table top and against a subdued background. But, James’ work is set apart by his naturalistic renderings of fruit and vegetables, his skill in decorative organization, and his delicacy of touch. In this instance, he personalized his picture with an elegant tendril at the top right that forms a cursive JP and a bolder “peeled” apple below. After Raphaelle’s death in 1825, James’ display of still life pictures increased significantly.

|

|

Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), Peaches Covered by a Handkerchief, 1819. Signed, lower right: Raphaelle Peale Pinxt. Oil on panel, 12½ x 18 inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2015-1-2).

|

|

Notable for its rich color, description of varied textures and subtle distribution of light, Raphaelle painted this picture for the wealthy, sophisticated Baltimore collector Robert Gilmor Jr. Raphaelle was already adept at still life and illusionistic painting by 1795, when he displayed five such works at the Columbianum exhibition alongside five portraits. Here he injects trompe l’oeil elements into an otherwise traditional picture. Typically small in scale, yet assertive and demanding of the viewer’s attention, Raphaelle’s compositions rarely include unusual objects, yet they often present unlikely juxtapositions or imaginative associations. Here the fabric used to keep insects like the trompe l’oeil wasp and fly off the peaches is not a utilitarian towel but a sheer kerchief of the type women frequently tucked into the bodice of a dress to insure modesty. It’s a choice that provokes the question of whether these peaches are simply from the garden or attributes of Venus?

|

|

Rubens Peale (1784–1865), From Nature in the Garden, 1856. Signed on basket: RuP to CWP 1856; inscribed, verso: By Rubens Peale from Nature in the Garden 1856. Oil on canvas, mounted on panel, 18¾ x 24¾ inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2010-70-3).

|

|

Described by his father, as his “right hand man” at his Philadelphia museum, Rubens later assumed ownership of his brother Rembrandt’s Baltimore museum before opening his own New-York Museum on Broadway in 1825. However, in 1839, in the wake of an economic panic and depression, Rubens relocated his family to Schuylkill Haven, Pennsylvania, where he farmed and pursued his love of botany. Only during the final decade of his life, instructed by his daughter, Mary Jane, did he turn to painting. This picture, which he gifted to his son, Charles Willson, his grandfather’s namesake, is an exuberant display of botanical specimens Rubens raised in his garden and greenhouse. Painting almost exclusively for his immediate and extended family, Rubens’ bold, individualized pictures are suffused with family memories and artistic prototypes. In this instance, he adapts the form of a bowl also seen in the work of Raphaelle and James.

|

|

| Sarah Miriam Peale was the youngest daughter of James and Mary Claypoole Peale. Like her sister Anna her abilities were publicly acknowledged by her election as an academician of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Instructed in still life painting and oil portraiture by James, she assisted him in his studio and later practiced both genres during a long independent career, which unfolded in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and St. Louis. Like Anna, she painted many high-profile individuals. During the early 1820s in Baltimore, Sarah studied with her cousin, Rembrandt, who occasionally facilitated commissions. Sarah’s patrons embraced her ability to capture their individual features and personalities in dynamic, visually interesting compositions. Her portrait of Cornelia Mandeville (1811–1841), the daughter of Henry D. Mandeville (1787–1878), a Philadelphia China trade merchant, manifests these qualities, with Cornelia’s firm gaze also projecting Sarah’s own intensity and assurance.

|

Sarah Miriam Peale (1800–1885), Portrait of Cornelia Mandeville (1811–1841), ca. 1830. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24⅞ inches. Gift of Marie Josephine Rozet and Rebecca Mandeville Rozet Hunt (1935-13-26).

|

|

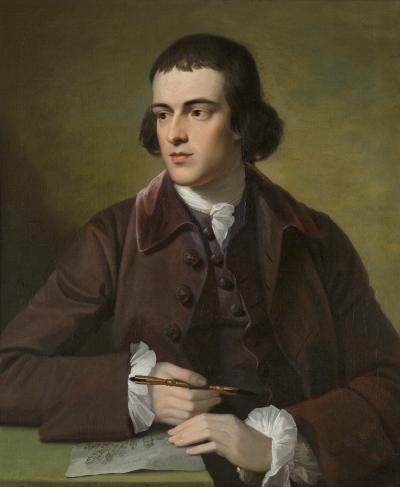

Anna Claypoole Peale (1791–1878), the eldest daughter of James and Mary Claypoole Peale, was among nineteenth-century America’s most prominent miniature painters. Instructed by James, she exhibited extensively at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, but also actively sought commissions in Washington, Baltimore, New York, and Boston. She painted well over 150 miniatures during her career, many of nationally renowned figures. Anna’s 1817 portrait of Philadelphian, John McAllister Jr. (1786–1877), a partner in his father’s prosperous optical equipment business, is a fine example of her realistic style, and is more akin to the works of her contemporaries than those of her father in its richer skin tones, more saturated color, and greater sense of physicality. James’ 1812 oil portraits of McAllister’s parents, also in the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s collection, suggest they shared family commissions.

|

|  |

Anna Claypoole Peale (1791–1878), Portrait of John McAllister Jr. (1786–1877), 1817. Signed and dated, lower left: Anna C./Peale/1817. Watercolor on ivory, 2⅞ x 2⅜ inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2008-112-5).

|

|

|

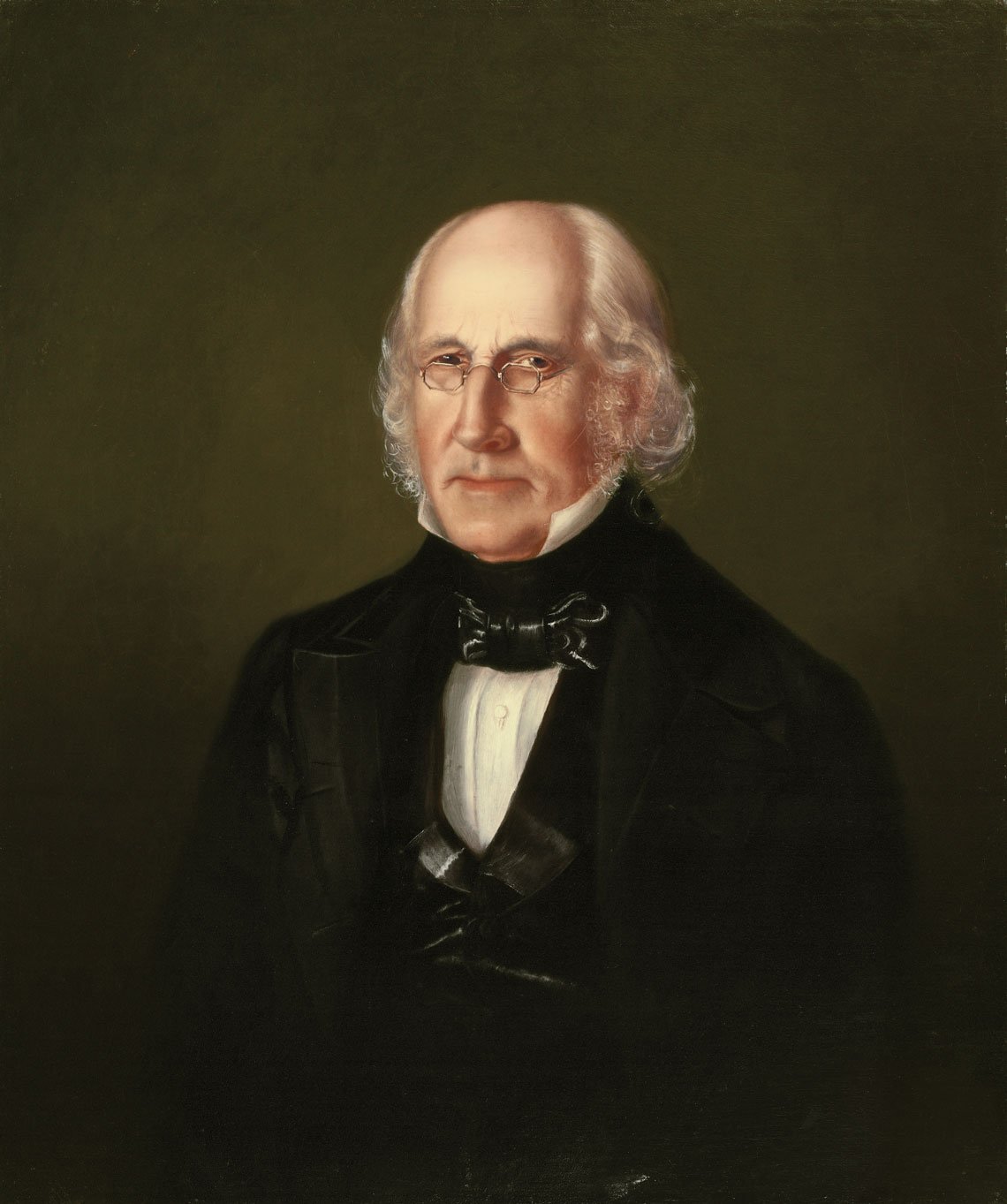

| Rembrandt was Charles’ second eldest son and the child who most closely met his expectations through his career as a portraitist and history painter. He was sixty-two when he painted this self-portrait for his second wife and student, Harriet Cany (1800–1869), during the first year of their marriage. His figure emerges from the darkness as his features are illuminated by light streaming across his face. His expression seems to resolve into a gentle smile, and details, like the shadows cast by his gold spectacles, draw the viewer into this intimate image. Its carefully rendered anatomy, meticulous execution, and high finish reflect his admiration for the neoclassical aesthetic he assimilated while studying in Paris, where he painted portraits of eminent European scientists and intellectuals for Peale’s museum. Throughout his long career, Rembrandt painted numerous self-portraits, which varied in size, format, and expressive quality.

|

Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860), Self Portrait, 1840. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2009-17-4).

|

|

Charles was seventy-seven when his interest in longevity led him to seek out the Guinean Muslim and former slave Yarrow Mamout, who was literate in Arabic, owned his own home, and had a bank account.2 Reputedly over 134 years old, but likely closer to eighty-three, Yarrow’s Georgetown neighbors explained to Peale that Yarrow’s calculations of age differed from western methods. Charles’ personal encounter with Yarrow confirmed his belief that advanced age was linked to “good temper,” and he noted in his diary that despite a life compromised by extraordinary hardships, Yarrow’s positive attitude, industry, self-discipline, frugality, perseverance, responsibility, resourcefulness, and temperance had sustained him. The portrait is a remarkably open and sympathetic encounter between artist and sitter and a rare image of ethnic and religious diversity in America prior to 1825. Its accomplished naturalism illustrates the development of Charles’ late style, which was indebted to lessons from his son Rembrandt.

|

|  |

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827), Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Muhammad Yaro) (ca. 1736–1823), 1819. Oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches. Purchased with the gifts (by exchange) of R. Wistar Harvey; Mrs. T. Charlton Henry, Mr. and Mrs. J. Stogdell Stokes, Elise Robinson Paumgarten from the Sallie Crozer Hilprecht Collection, Lucie Washington Mitcheson in memory of Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson for the Robert Stockton Johnson Mitcheson Collection, R. Nelson Buckley, the estate of Rictavia Schiff, and the McNeil Acquisition Fund for American Art and Material Culture (2011-87-1).

|

|

|

| Titian was the fourth child of Charles and his second wife, Elizabeth DePeyster (1765–1804), and the namesake of his brother, pictured in the Staircase Group, who died of yellow fever in 1798. A naturalist, explorer, and contributor to the scientific and ethnographic collections of the Peale museums, he embarked on his first scientific expedition at eighteen. Ultimately, he joined expeditions in North America, Central and South America, and the South Pacific. His most remarkable legacy, however, was his study, collecting, propagation, and preservation of butterflies. Late in life, as he completed his three-volume manuscript on these insects and crafted boxes for their display, he also began to paint them.3 In this delicate oil of exotic butterflies, Titian presents his specimens alive and partnering in flight across a luminous sky. It is a perfect union of artistry with the eye of the naturalist.

|

Titian Ramsay Peale II (1799–1885), Caligo Martia (Butterflies), 1878. Signed and dated, front, lower right, in brush and black ink: Titian R. Peale/March 1878; label on back of frame: CALIGO MARTIA./A rare Butterfly from Porto Alegre, rio grande, Brazil./Painted from Nature for Miss Catherine Bohlen/By Titian R. Peale, March 1878. Oil on textured coated paper, 13-5⁄16 x 10-13⁄16 inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2009-18-7).

|

|

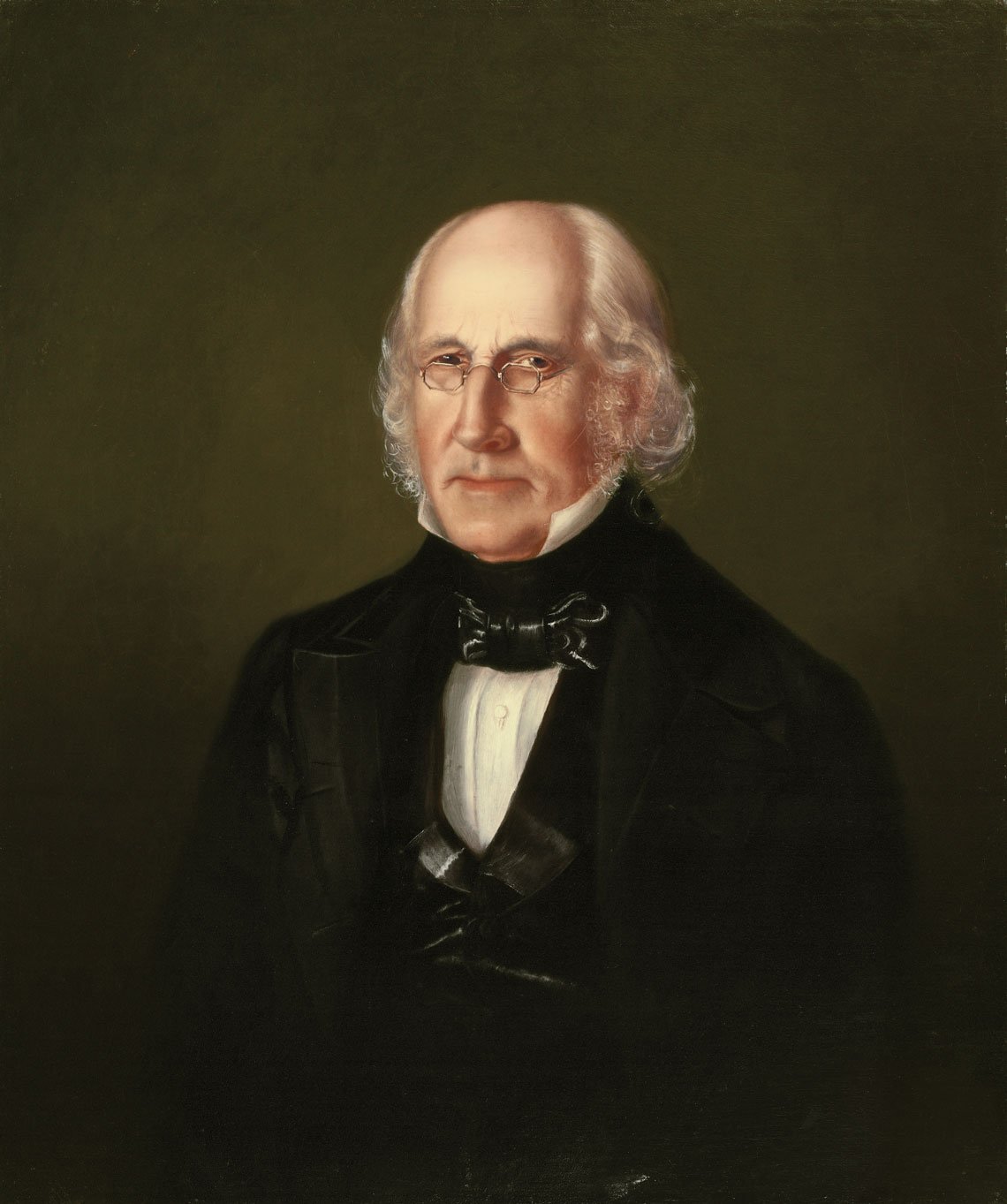

Mary Jane (1827–1902) was the only daughter of Rubens Peale and Elizabeth Burd Patterson Peale (1784–1865). Keenly aware of her family heritage, she noted in her diary that she began this portrait of her father the day after what would have been her grandfather, Charles’ 114th birthday. Her study with her uncle Rembrandt is illustrated by her careful modeling of Rubens’ cheeks, nose, lips, and face, which are painted in warm and silvery tones. As in Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait of 1840, the reflections from Rubens’ glasses are visible on his cheeks. Seemingly amused, Rubens shoots the viewer a sideways glance, as the delicate and springy silver curls on either side of his head catch the light and energize his likeness. Although productive, Mary limited her output to commissions from friends and family, painting both original works and copies largely after works by Rembrandt, Raphaelle, and James.

|

|  |

Mary Jane Peale (1827–1902), Rubens Peale, Aged 71 (The Artist’s Father) (1784–1865), 1855. Signed and dated, verso: Mary J. Peale/Woodland/April 1855. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Gift of the McNeil Americana Collection (2009-17-2).

|

|

The Art of the Peales, by Carol Eaton Soltis, will be complemented by an online component currently being created for the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s website, where the book is also available. The site will provide updated information on publications, provenance, and exhibition records relating to the museum’s Peale collection.

A symposium, Continuing Curiosity: The Art of the Peales, will be held on February 17, 2018 in the museum’s Perelman Building. Click here for information about purchasing the catalog. For more information about the exhibit, visit www.philamuseum.org. All images courtesy, The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Carol Eaton Soltis is a project associate curator, American Art, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, specializing in the work of the Peales.

This article was originally published in the 18th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

1. The Promised gift of the McNeil Americana Collection was established in 2007.

2. Carol Eaton Soltis, The Art of the Peales in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Adaptations and Innovations (Philadelphia: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2017), 195-98, 306 n.508.

3. Titian’s four-volume manuscript, “Butterflies of North America, Diurnal Lepidoptera: Whence They Come, Where they Go, and What They Do, illustrated and Described by Titian R. Peale” is in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History Research Library, New York. Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences owns over one hundred leather bound, glazed boxes created by Titian to house and display his extensive collection of specimens.