Top Museum Acquisitions: 2018 in Review

| |

Fig. 1: John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), John Alfred Parsons Millet, 1892. Oil on canvas, 36 ¼ x 24⅛ inches. San Diego Museum of Art; Purchased with funds from a variety of donors. |

This past year saw more museums taking active roles in social (and sometimes political) discourse, most commonly through programs and exhibitions. Last fall, for instance, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts offered a month-long series of talks about propaganda, black lists, paranoia, and the Red Scare; the High Museum of Art in Atlanta screened a documentary about Tommie Smith’s raised fist gesture during the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. But it hasn’t always worked out as planned. In September, an exhibition at the University Art Museum at Cal State Long Beach that focused on police violence against African Americans morphed into a protest against the museum’s firing, a few days before the show’s opening, of its director Kimberli Meyer. Museums were also the focus of frustratiom — from employees protesting low wages (MoMA PS1 in Long Island City), calls for increased diversity (the Brooklyn Museum’s hiring of a white consulting curator in the African art department), financial ties to corporations (from Big Pharma to non-green energy production), to artists and employees protesting the lack of government preparedness and funding after a devastating fire at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro this past summer. Controversy also continued with the selling through Sotheby’s of deaccessioned works by the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, for their endowment, and calls for the repatriation of cultural objects at a number of museums.

An important role that museums continue to play is the acquisition of objects and art. While not every museum needs an iconic work such as a Monet haystack, each institution has its wish lists. To house growing collections (and to integrate new technologies and reinterpret displays), many museums expanded their footprints in 2018. Among these were New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which is expanding (again) from 135,000 to 175,000 square feet ($450 million); the Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland, which increased the visitor capacity from 25,000 to 100,000 through a 200,000 square foot expansion ($200 million); the Studio Museum in New York City, which will erect an entirely new 82,000 square-foot building at its current site ($175 million); the Holocaust Museum Houston, which increased from 21,000 to 57,000 square feet ($49.4 million); and the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, which is adding more exhibition galleries ($6.2 million).

Let’s take a look at a selection of museum acquisitions from the past year. >>

|

Fig. 2: Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), Sunburst in the Riesengebirge, ca. 1820–30. Oil on canvas, 25½ x 31½ inches. Saint Louis Art Museum. |

| |

Fig. 3: William Dering (active 1734/1735–1755), Joyce Armistead Booth (Mrs. Mordecai Booth), Williamsburg, Va., ca. 1745. Oil on canvas. Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; gift of Julia Miles Brock, Edward Taliaferro Miles and Georginana Serpell Miles in memory of their mother, Alice Taliaferro Miles (2018-165, A&B). |

Trophy Finds

The San Diego Museum of Art purchased Lucas Cranach the Younger’s circa-1540 Nymph of the Spring (with funds provided by Toni Bloomberg; Gene and Taffin Ray; an anonymous donor; Kevin Rowe & Irene Vlitos Rowe, and the museum’s acquisition fund) and John Singer Sargent’s 1892 oil portrait of John Alfred Parsons Millet (Fig. 1). Paintings by German artist Caspar David Friedrich are rare on the market, and only a small number of U.S. museums have any. The Saint Louis Art Museum purchased the artist’s circa-1820–1830 Sunburst in the Riesengebirge at Sotheby’s London for $2.75 million (Fig. 2).

Authenticated lifetime casts of works by Frederic Remington can be difficult to come by, since so many posthumous editions, some suspect, of the artist’s work abound in the market. The Newark Museum got the real thing. The Rattlesnake (cast in 1906) and Mountain Man (cast in 1916 and authorized by Remington’s widow), are part of a bequest from Marie L. Garibaldi (d. 2016), the first woman appointed to the New Jersey Supreme Court.

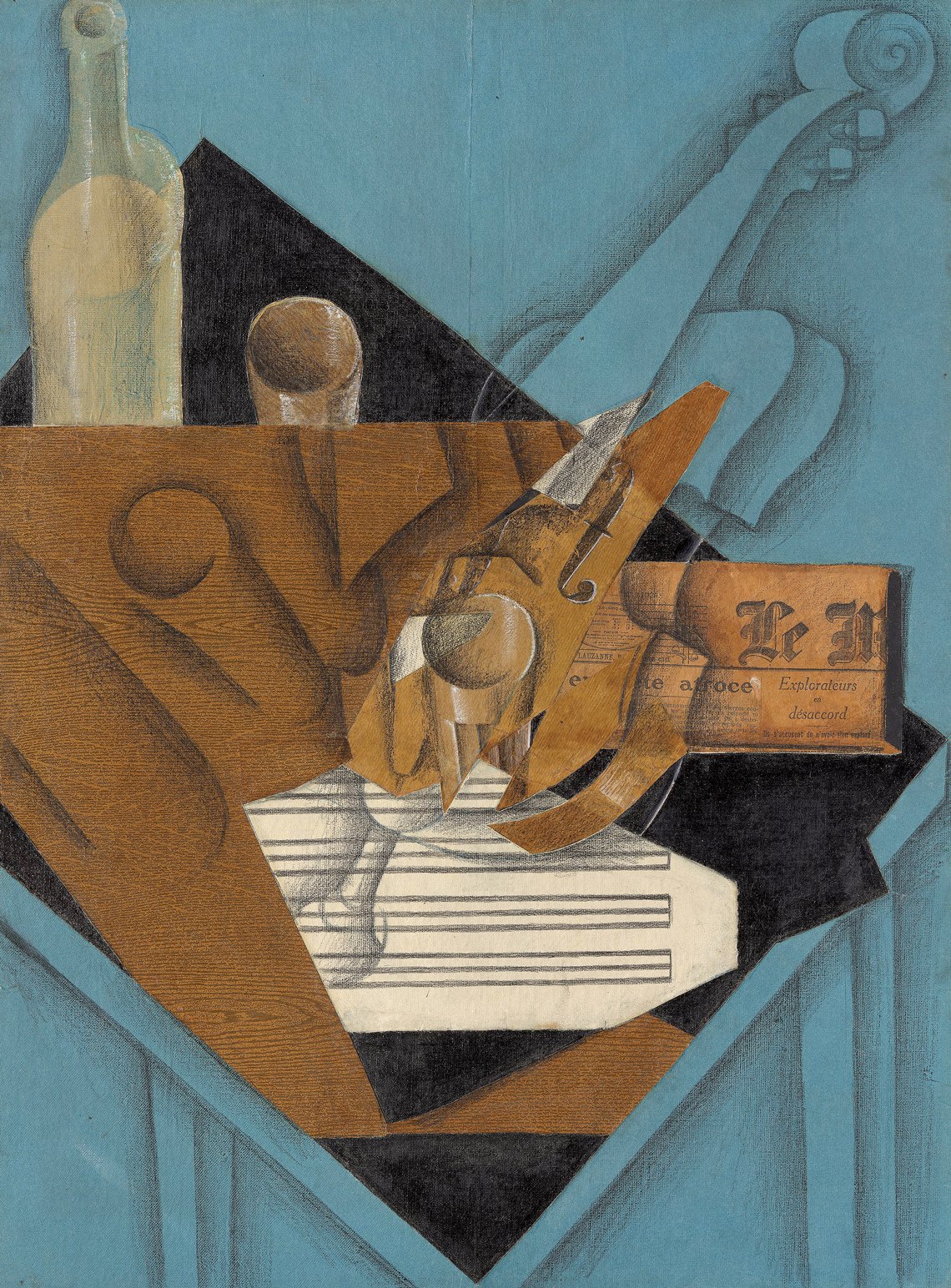

A gift from the sitter’s descendants, a large-scale, circa-1745 portrait of Joyce Armistead Booth (Fig. 3) by William Dering of Williamsburg, Virginia, in its original frame, became the fifth example of the artist’s work to enter the collection of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; only six examples are known. Having founded The Met’s Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art in 2013 and gifted the institution a nearly $1 billion collection of Cubist artwork, in September, Lauder added to this gift with a 1914 Juan Gris still life The Musician’s Table, purchased at Christie’s in May for $31.8 million (Fig. 4).

|  | |

Left: Fig. 4: Juan Gris (Spanish, 1887–1927), The Musician’s Table, 1914. Charcoal, wax crayon, gouache, cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper, blue and white laid papers, transparentized paper, newsprint, and brown wrapping paper; selectively varnished on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection; Purchase, Leonard A. Lauder Gift, 2018 (2018.216). Right: Fig. 5: Childe Hassam (1859-1935). Bleak House, Broadstairs, 1889. Watercolor on paper, 13 x 9 in. Collection of the Canton Museum of Art, Canton, Ohio. The house at the top of the painting is where Charles Dickens wrote David Copperfield. | ||

The Canton Museum of Art in Ohio bought Childe Hassam’s Bleak House, Broadstairs (1890) from a private collector (Fig. 5). Getting a work by the artist was on the institution’s “wish list,” according to Max Barton, executive director of the museum. Fredric Edwin Church’s Valley of Santa Isabel, New Granada, 1875 (in its original frame designed by the artist) has become the most significant Hudson River School painting in The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Art’s collection. Deaccessioned from the Berkshire Museum, it was purchased in a private transaction for more than $4 million. With the lawsuits completed over the Berkshire Museum’s decision to deaccession paintings from its permanent collection, we now know that one of its most notable pieces, Norman Rockwell’s Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1950), put up for sale in April, is going to the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, set to open in Los Angeles in 2022. Founder movie director George Lucas purchased the work for a sum assumed to be between $20 and $30 million. The work is currently on loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

|  | |

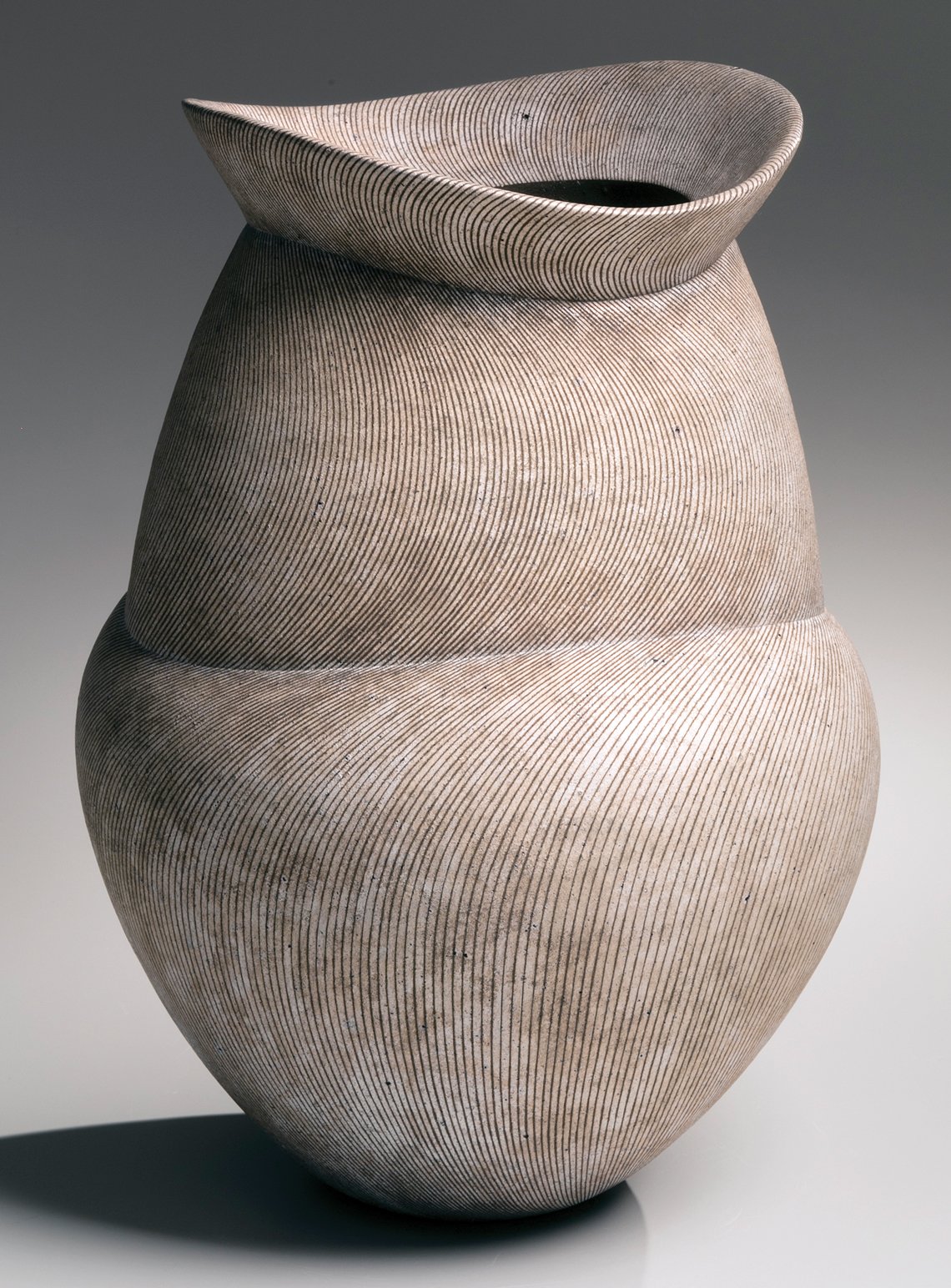

Left: Fig. 6: Ruba Rombic toilet bottle, Reuben Hailey (1872–1933), designer, Consolidated Lamp & Glass Co. (1893–1932), 1928–1932. Glass. Carnegie Museum of Art, James L. Winokur Fun and the Elizabeth A. Drain Fund (2018.19.A–B). © Public domain. Right: Fig. 7: Iguchi Daisuke (Tochigi, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan, b. 1975), Shutoginsaiko; Ash-coated and silver slip vessel, 2017. Ash-coated stoneware with silver slip, 18 x 11¾ x 11⅜ in. Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection; Purchase, Tabriz Fund (2018.004). | ||

| |

Fig. 8: Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997), Shipboard Girl, 1965. Offset lithograph on white wove paper, Sheet: 27-3/16 x 20-1/4 in., Image: 26-1/8 x 19-3/16 in. Edition: unknown. Whitney Museum of American Art (2018). © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. |

Modern and Contemporary

The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburg, drew from two of its purchase funds to acquire a Reuben Haley-designed (and Cubist-influenced) lilac-colored toilet bottle from 1928–1932 (Fig. 6), part of the Ruba Rombic line of glassware manufactured at the Consolidated Lamp and Glass Company in Coraopolis, Pennsylvania. Among the 209 items acquired by the Arkansas Arts Center this year were works by Russian avant-garde artist Alexander Archipenko, American impressionist John Singer Sargent, and a ceramic vessel by Japanese ceramicist Iguchi Daisuke (Fig. 7).

The Brooklyn Museum added to its holdings in contemporary art with Do Ho Suh’s 2003 installation The Perfect Home II (gift of Lawrence B. Benenson) and the purchase of a large-scale untitled abstract painting, while the Whitney Museum of American Art was the recipient of approximately four hundred artworks in a variety of media from the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, which has been in the process of winding down its activities. The gift was one of the largest single artist donations in the museum’s history (Fig. 8). The Museum of Modern Art acquired a number of important collections, including a gift of ninety works of contemporary Latin-American art and the purchase of a collection of 324 early European Modernist works on paper.

A quiet trend has been the number of major gifts to college and university art museums. With good reason: Give a Jackson Pollock to the MoMA, and it likely will go into storage, because the museum has eighty-six of them. Give a Pollock to the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, and your gift will go on display right away. In fact, a purchase (made possible by donor funds and a partial gift from the previous owner) brought Pollock’s Composition with Masked Forms (1941) to the museum. The work anticipates Pollock’s drip paintings begun in 1947.

A gift of fifty-plus artworks by Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 9) and by contemporaries and later artists he influenced, such as Diane Arbus, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Irving Penn, Man Ray and Tristan Tzara, was donated to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., by Barbara and Aaron Levine, who are themselves major Duchamp collectors. Founder Michael A. Mennello promised the Mennello Museum of American Art in Orlando its largest gift ever of fourteen paintings and five sculptural works valued at nearly $9 million. Included are artists from the Ashcan School of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Arts Students League in New York including John Sloan (Fig. 10), George Bellows, Robert Henri, and others.

|

Fig. 9: Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), With Hidden Noise (A Bruit Secret). Signed Marcel Duchamp, dated 1964, numbered 7/8 and engraved “A Bruit Secret 1916 /Edition Galerie Schwarz, Milan.” Assisted Readymade: ball of twine (containing unknown object) between two brass plates joined by four long bolts. Height: 4½ in. Courtesy of Sotheby’s. © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2018. Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden. |

|

Fig. 10: John Sloan (1871–1951), Roof Chats, 1944/1950. Tempera and oil varnish on panel, 16 x 20 inches. Collection of the Mennello Museum of American Art; Gift of Michael A. Mennello ( 2018). |

|

Fig. 11: Sam Doyle (1906–1985), St. Helena’s Black Merry Go Rond, ca. 1980-83. House paint on metal, 26 x 48 inches. California African American Museum. |

| |

Fig. 12: Beauford Delaney (1901–1979), Self Portrait in a Paris Bath House, 1971. Oil on canvas, 21¾ x 18 inches. Knoxville Museum of Art. All images: © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator. |

African-American Art

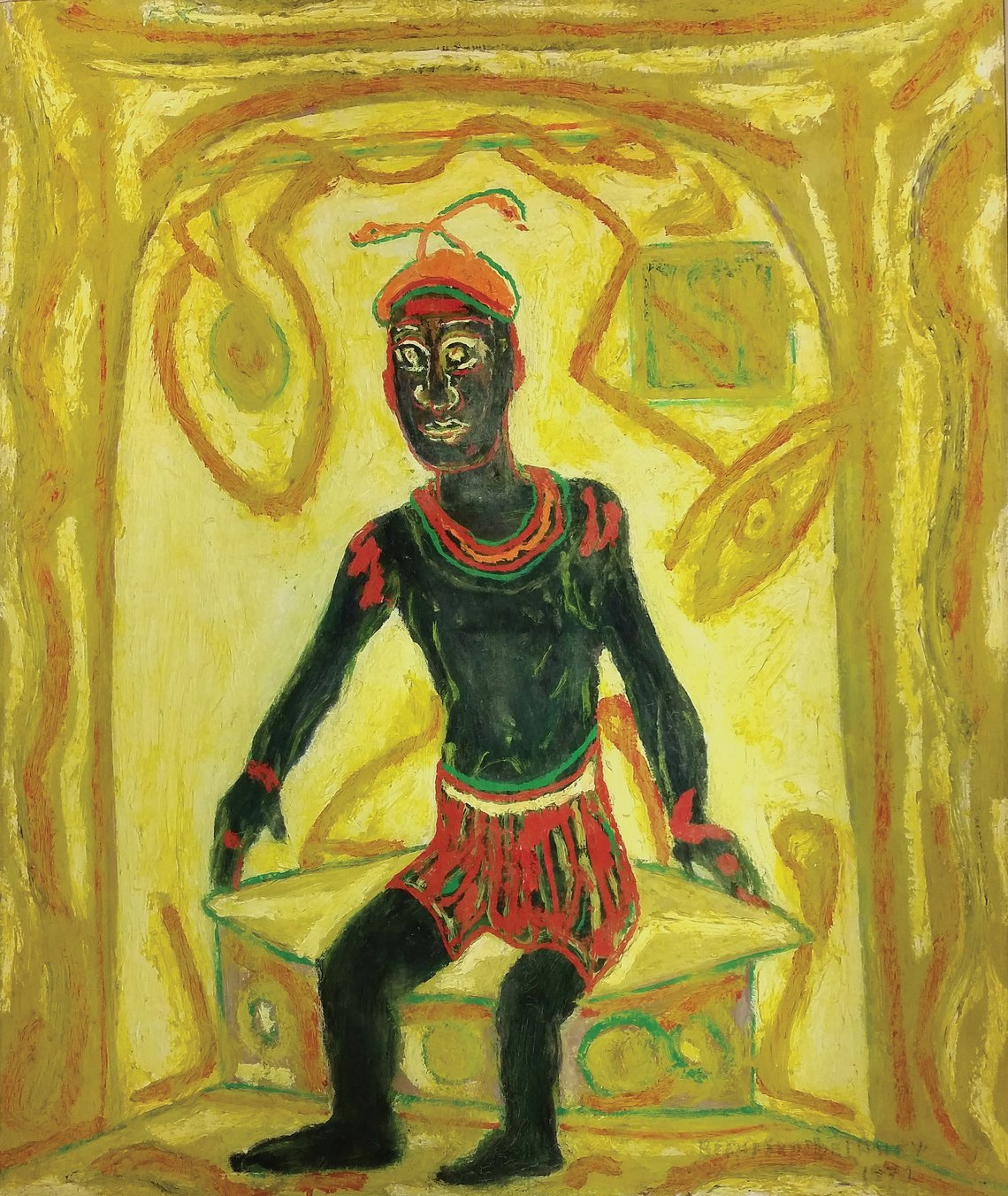

Civil rights activist and art collector Peggy Cooper Cafritz donated her collection of six hundred and fifty works of contemporary art by artists of African descent to the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, D.C. Most of the artworks went to the Studio Museum, and include pieces by Nina Chanel Abney, Derrick Adams, Sanford Biggers, Nick Cave, Noah Davis, and Kerry James Marshall, among others. Collector and scholar Gordon W. Bailey donated thirty-two paintings, sculpture, and mixed-media pieces by such artists as Sam Doyle (Fig. 11), Georgia Speller, Jimmy Lee Sudduth and Purvis Young, to the California African American Museum in Los Angeles.

The Baltimore Museum of Art sold works by such artists from its permanent collection as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Franz Kline to raise funds to acquire works by African-American artists. So far, the museum has bought paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Amy Sherald, and Jack Whitten, a sculpture by Wangechi Mutu and two film pieces by Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelly. The Getty Research Institute acquired the archive of artist Betye Saar as part of its newly announced African-American Art History Initiative.

Also of note is the accession of the photographic archive of Stephen Shames, best known as the Black Panther Party’s photographer between 1967 and 1973, by the Briscoe Center at the University of Texas; the purchase of twelve works by painter Beauford Delaney (Fig. 12) by the Knoxville Museum of Art in Tennessee; and, the transfer of fifty-one artworks by thirty African-American self-taught artists from the Atlanta-based Souls Grown Deep Foundation to the Brooklyn Museum, Morgan Library & Museum, Spelman College Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas Museum of Art, and the MFA, Boston.

Art by Women

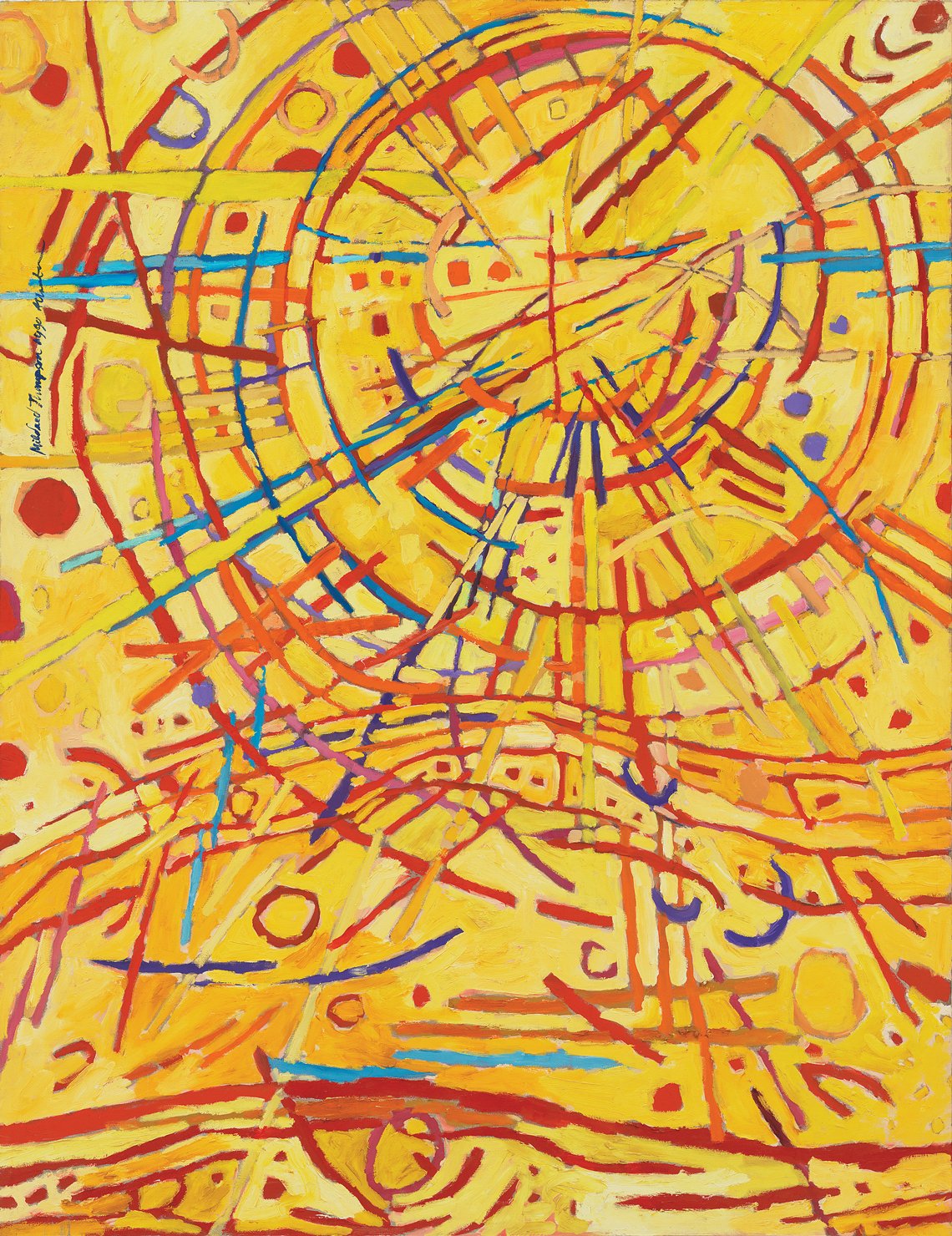

Museums are also catching up in their representation of women artists, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum was helped by a gift from the Kallir Family of ten paintings by Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses that will take place over the span of seven years. All ten paintings will figure in a traveling Grandma Moses exhibition slated for fall 2023. Also in Washington, D.C., the National Museum of Women in the Arts received one abstract painting by African-American artist Mildred Thompson from her Magnetic Fields series (Fig. 13) and one of her wood pictures. This past spring, the collectors committee of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art contributed approximately $2.6 million to purchase works by six women artists, including Martha Boto, Betye Saar, Jennifer Bartlett and Julie Mehretu. Michael Govan, the museum’s director, has declared its intention to put women artists “front and center.”

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 13: Mildred Thompson (1936–2003), Magnetic Fields, 1990. Oil on canvas, 62 x 48 inches. Gift of the Georgia Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in honor of the 30th anniversary of the Georgia Committee and the National Museum of Women in the Arts; ©The Mildred Thompson Estate; Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York. Right: Fig. 14: Louise Nevelson (1899–1988), Cascades-Perpendiculars II (Night Music), 1980–1982. Wood painted black, 82 x 33 x 38 in. San José Museum of Art; Gift of the Lipman Family Foundation, (2017.17.05). Image courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York. | ||

Others acquiring the work of women artists are the Cleveland Museum of Art, which purchased Emma Amos’s Sandy and Her Husband (1973): the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which bought a group of thirty-seven photographs by Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide; the San Jose Museum of Art, which received as a donation five works by sculptor Louise Nevelson (Fig. 14) from the collection of Beverly and Peter Lipman of Portola Valley and the Lipman Family Foundation; and the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, which bought directly from the Alice Neel estate Julie and the Doll (1943). The J. Paul Getty Museum has added Camille Claudel’s 1887 bronze Torso of a Crouching Woman. Slowly, the Getty has been building its holdings of artwork by women artists and has works by sculptors Luisa Roldàn (La Roldana), Barbara Hepworth, and Elisabeth Frink.

Daniel Grant is a freelance writer specializing in the arts industry.

This article was originally published in the 2019 Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com.