Collecting Nantucket: Connecting the World

|

The island of Nantucket, twenty-five miles off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, is well known for its whaling heritage and, for more than one hundred and fifty years, it has been famous as a summer holiday destination as well. The many threads that make up the island’s history meet in the collections of the Nantucket Historical Association (NHA), which celebrates its 125th anniversary in 2019 by providing the loan exhibition to the Winter Show (formerly the Winter Antiques Show) in New York City. The best the association has to offer is reflected at the Winter Show by spectacular examples of sailors’ scrimshaw, journals from sea-captain’s wives, and art inspired by the whale hunt and ocean journeys to the far side of the world. The island’s diverse people, from Native Wampanoag sailors and English settlers to African-American businessmen and colorful mariners, are represented in portraits by Gilbert Stuart, Eastman Johnson, Elizabeth R. Coffin, Spoilum, and William Swain. The association is also pleased, during the 200th birthday year of Herman Melville, to be displaying artifacts related to the 1820 tragedy of the whaleship Essex, whose destruction by an angry whale inspired key aspects of Moby-Dick.

The name “Nantucket” or “faraway place,” comes from the island’s first inhabitants — the Wampanoags, one of the Algonquian peoples of southern New England. From the time Nantucket was formed by glacial melting five thousand years ago, the island was already home to the Wampanoags. When the first English settlers arrived in 1659, they adopted the native Wampanoags’ fish and shellfish foodways and introduced sheep herding and cattle grazing to the island in hopes of developing trade. During their first fifty years on island, the English population of Nantucket grew to seven hundred, while the three thousand-person native community dwindled to eight hundred, due to poverty, disease, and alcoholism caused by the English presence.

|  | |

Left: Fig. 1: The Pollard Limner (active ca. 1690–1730), attributed, Mary Gardner Coffin, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas; 29¾ x 25 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of Eunice Coffin Gardner Brooks (1924.3.1). Right: Fig. 2: Candlesticks, unknown maker, mid-nineteenth century. Whale bone, whale ivory; H. 9½, W. 4, D. 4 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of the Friends of the Nantucket Historical Association with support of the Gosnell and Geschke families (2008.10.1 & .2). | ||

The NHA’s portrait of Mary Gardner Coffin (1670–1767) represents the second generation of English settlers on the island (Fig. 1). It is the earliest known painted portrait of a Nantucketer, but it was not painted on Nantucket. The island during this period was isolated and rural, with an economy too small to nourish its own fine arts traditions. Even as the island’s trade expanded internationally from mid-century on, the increasing cultural dominance of Quakerism and its doctrine of simplicity limited the development of a taste for the arts, and citizens of means who sought finer things had to seek them in mainland cities or in Europe.

When agriculture and shepherding produced poor results on sandy Nantucket, the English settlers turned to whaling. Hiring predominantly Wampanoag crews, they started shore whaling in small boats around 1690. Longer trips “over the horizon” began around 1715, growing to two- and three-month cruises as far as Newfoundland waters around 1730 and to four- and five-month cruises to the Azores and West Indies in the 1760s. By 1770, whale products were colonial New England’s second most valuable export, after codfish, and Nantucket provided over half of the region’s production. On the eve of the American Revolution, Nantucket ships were making voyages of up to a year to the Guinean and Brazilian coasts, and in 1791 a Nantucket whaler crossed into the Pacific Ocean for the first time.

For about a century and a half, whale hunting drove Nantucket’s economy, bringing the island prosperity from the sale of refined oils and clean-burning, bright spermaceti candles. A spectacular pair of turned candlesticks made of sperm-whale ivory and bone perfectly symbolize the island’s cetacean-fueled economy (Fig. 2). The island’s specialty enterprise also vitally linked its people to the far corners of the globe. This success flowed, too, from the influence of the plain, frugal, and pragmatic philosophy of the Quakers, whose religious doctrines dominated island life from the 1720s to the 1820s. Quaker theology emphasized industry and thrift and accepted material prosperity as a sign of God’s favor. It also encouraged equality of the sexes, education for both men and women, and plainness in dress and living.

|

Fig. 3: Thomas Birch (1779–1851), View of the Town of Nantucket, ca. 1811. Oil on canvas; 17¼ x 27 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of Robert M. Waggaman in memory of his parents, Floyd Pierpont and Jean Mackenzie Waggaman (1974.21.1). |

|

Fig. 4: Engraved panbone, unknown English artist, ca. 1830. Whale bone and ink; H. 39⅝, W. 14½, D. 6 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; acquired in trade from David Gray (1956.3.1). |

The island’s reliance on the water forms the theme of Thomas Birch’s View of the Town of Nantucket (Fig. 3), the earliest known painting of the town. Maritime activity fills the scene, with whalers and coastal traders lining the wharfs and passing to and fro. Philadelphian Joseph Sansom visited the island around 1810 and described the lively scene with its wood stores and houses and its two prominent Congregational meeting-house tower. The numerous Quaker meeting houses, being very plain, did not announce themselves on the Nantucket skyline.

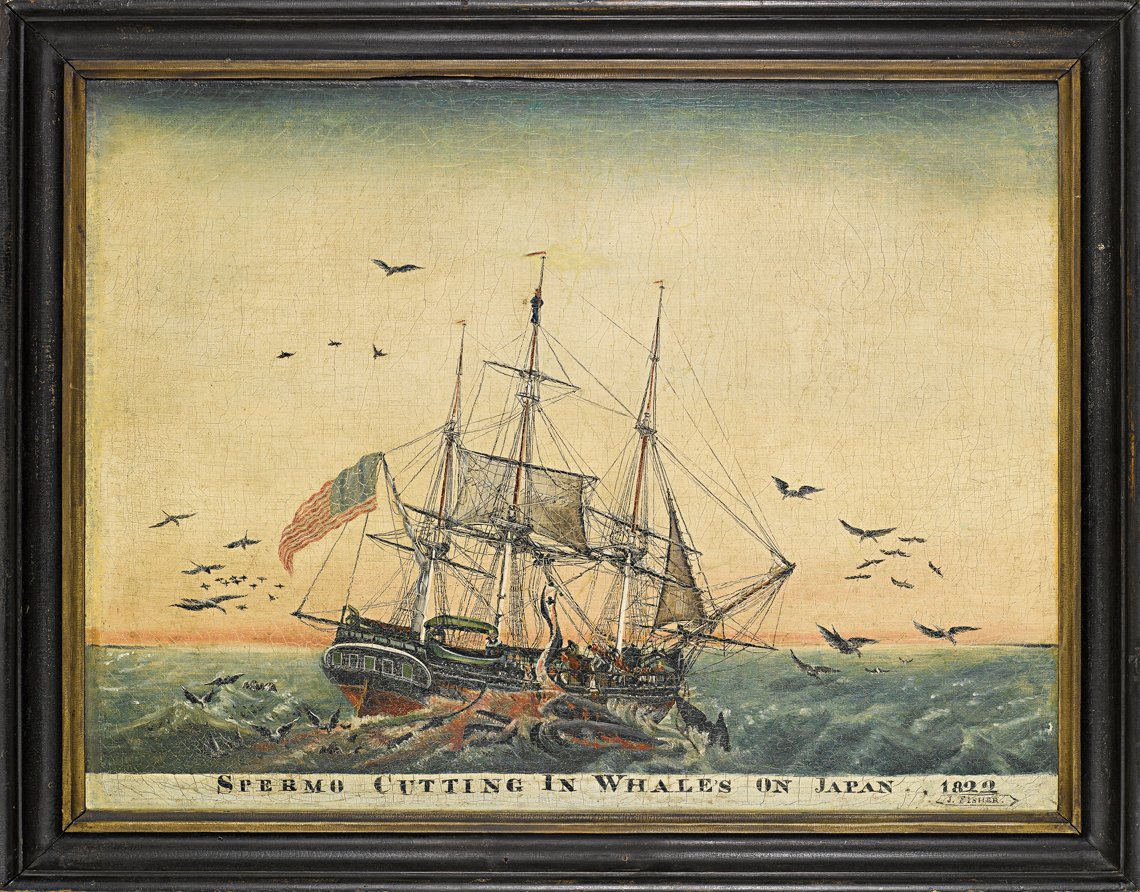

Numerous artifacts reflect the awful labor that underpinned Nantucket’s whaling wealth. An outstanding decorative engraving on part of the jawbone of a sperm whale depicts a range of whaling activities on the high seas (Fig. 4). While small whaleboats hunt their prey, an enraged whale smashes a boat with its tail, propelling men and equipment into the air. Back aboard one of the motherships, men remove the blubber from a carcass while a stain of red spreads across the water. Similarly, a pair of paintings record the Nantucket ship Spermo in the course of a profitable voyage in 1820–1823. In Spermo Cutting In Whales On Japan (Fig. 5), the artist J. Fisher precisely captures the process of cutting the blubber off a slaughtered whale, while his Ship Spermo Trying With Boats (Fig. 6) shows the noisome and smoke-filled practice of boiling whale blubber to render it into storable oil. The scenes reflect the backbreaking and dangerous labor that gathered millions of gallons of oil to light and lubricate the industrial revolution.

|  | |

Left: Fig. 5: J. Fisher (life dates uncertain), Spermo Cutting In Whales On Japan, 1822, ca. 1823. Oil on canvas; 18¾ x 24¾ in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of the Friends of the Nantucket Historical Association (2008.31.2). Right: Fig. 6: J. Fisher (life dates uncertain), Ship Spermo Trying With Boats Among Whales On California, 1821, ca. 1823. Oil on canvas; 18¾ x 24¾ in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection, gift of the Friends of the Nantucket Historical Association (2008.31.1). | ||

| |

Fig. 7: Piece of twine, made by Benjamin Lawrence (1799–1879), 1820–1821. Natural fibers on card in ivory frame, 4 x 5 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of Alexander Starbuck (1914.15.1). |

Extraordinary terrors sometimes augmented the more routine hazards of whaling life. On November 20, 1820, an enraged sperm whale, eighty-five-feet long and weighing about eighty tons, rammed the Nantucket ship Essex while the ship hunted whales near the equator in the remote Pacific. The ship promptly filled with water and rolled over, a total wreck. Fearing cannibals on the closest islands — twenty to thirty days’ sail away — Captain George Pollard Jr. and his crew of nineteen set course in small boats for South America, hoping to run three thousand miles against contrary winds before exhausting the limited food and water they could carry. Three months later, passing ships picked up just five emaciated survivors from the boats. Three other men were stranded on a remote island, and twelve men were dead — seven of them eaten in desperation by their starving shipmates.

This story, as told in an 1821 book by First Mate Owen Chase, fired the imagination of young Herman Melville when he was a whaler in the early 1840s, and it inspired, in part, Captain Ahab’s quest for the malevolent white whale in Moby-Dick, published in 1851. This mammoth literary heritage notwithstanding, a short length of hand-twisted twine (Fig. 7) in the NHA’s collection, made by twenty-one-year-old Benjamin Lawrence while in one of the boats, is all that remains of the doomed Essex.

| |

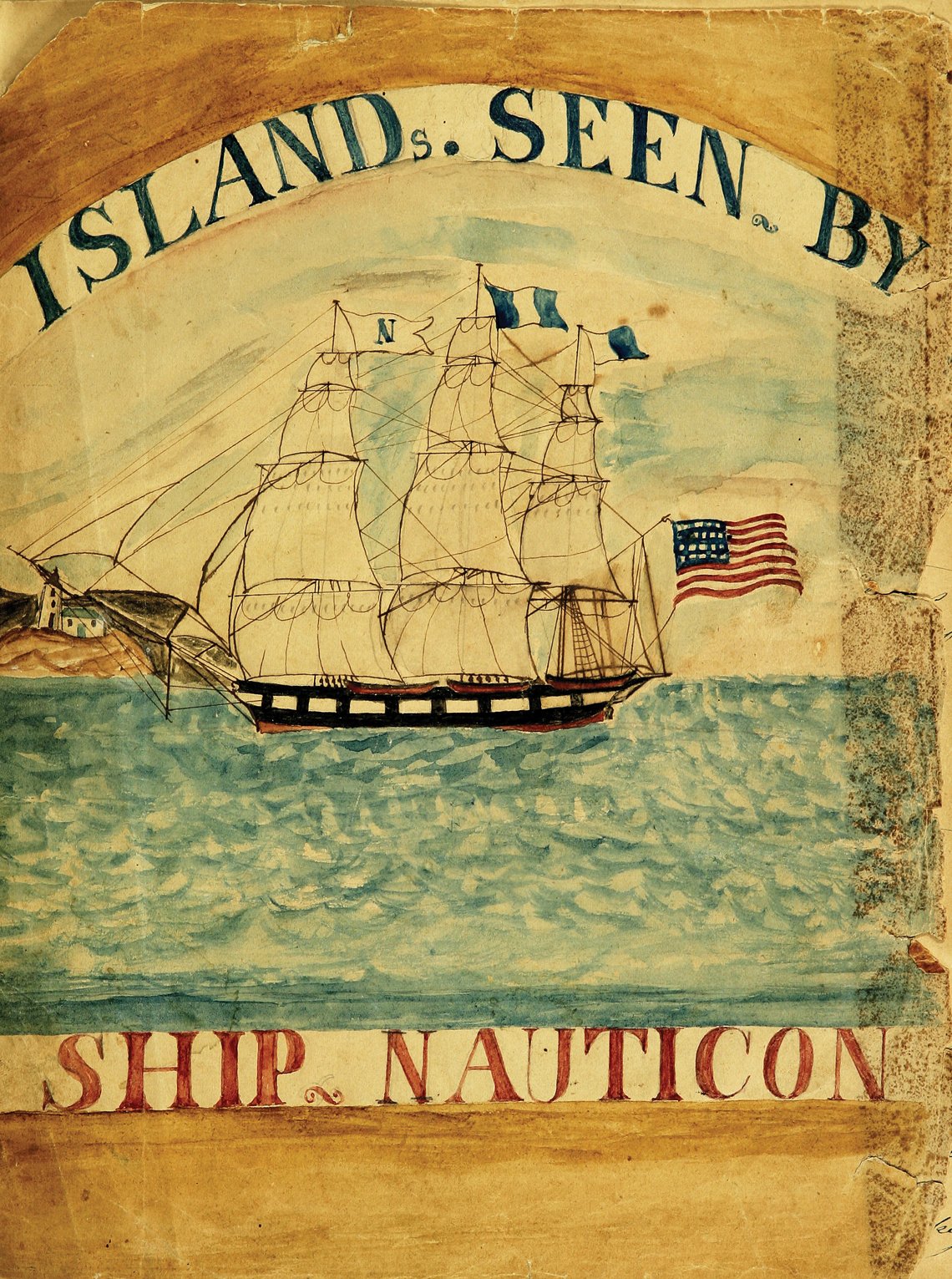

Fig. 8: Susan Veeder (1816–1897), Cover of “Islands Seen by Ship Nauticon” journal 1848–1853). Ink and watercolor on paper; 10¼ x 8 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of the Friends of the Nantucket Historical Association (Ms. 220 log 347). |

Beginning in the 1820s, some enterprising women joined their sea-captain husbands on whaling voyages to the Pacific, often with their children. Among them was Susan Veeder, who sailed with her husband Charles and their young sons on the ship Nauticon between fall 1848 and spring 1853. The voyage was an eventful one, and Susan described and illustrated it in lively detail in a private journal (Fig. 8). Four months out from Nantucket, Susan gave birth to a daughter, Mary Frances, at Talcahuano, Chile. All was well with the family until early 1850, when the child was accidentally poisoned by medicine while the ship lay at Tahiti.

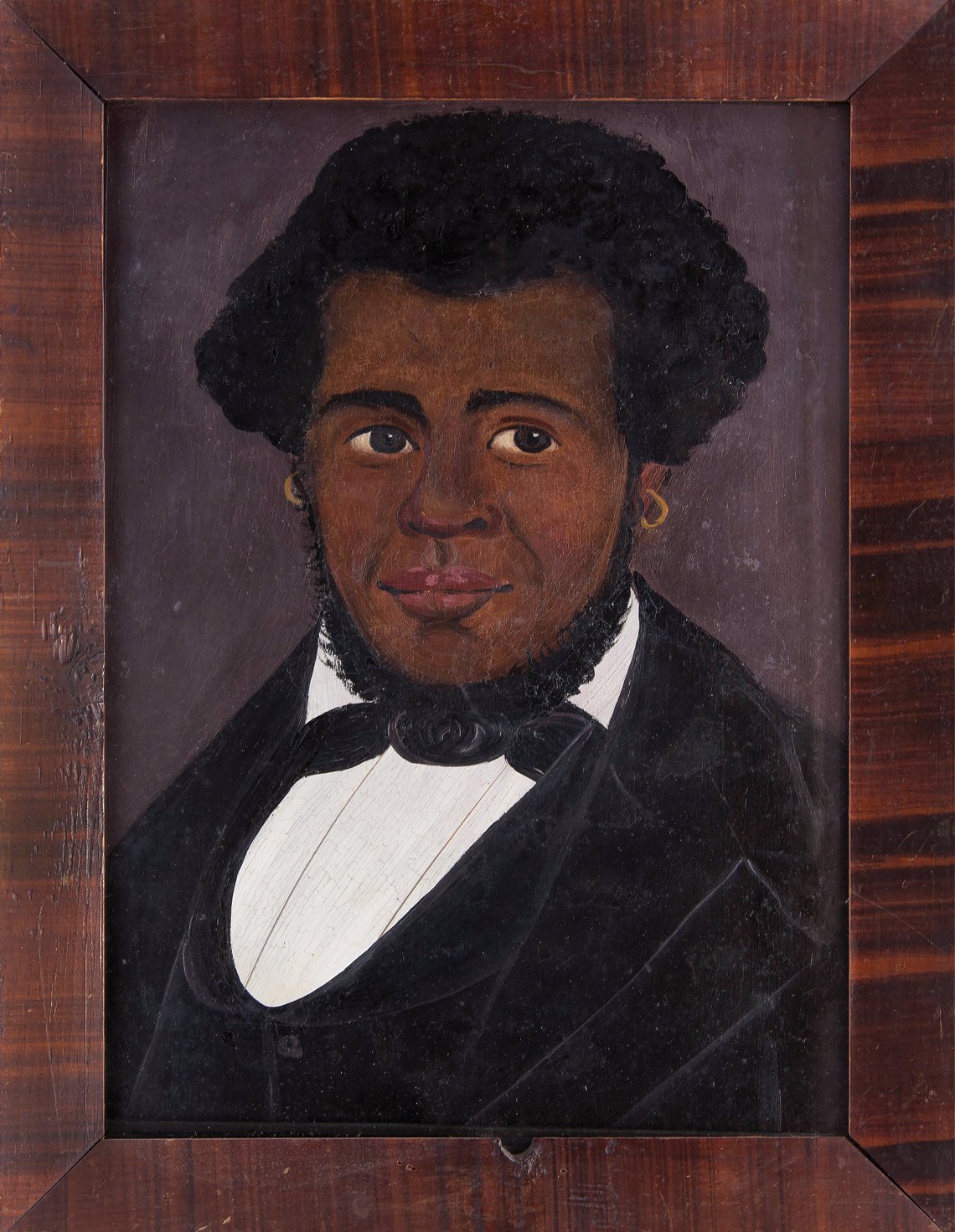

Whaling provided economic opportunities for many islanders, including African Americans and Native Americans. Sampson Dyer (1773–1843), a man of mixed African and Wampanoag heritage, and his wife settled in the 1790s in the island’s small but thriving community of free black sailors and tradespeople. Dyer sailed on Nantucket sealing and trading voyages to China, where he had his portrait painted by the Chinese artist Spoilum (Fig. 9). Captain Absalom F. Boston, whose likeness is also preserved in an important painting in the NHA collection (Fig. 10), commanded the island’s first all-black whaling crew when he took the ship Industry out to the Cape Verde Islands in 1822. He was a third-generation islander and engaged in real-estate trading and innkeeping after seafaring. He and his family figured in a number of important milestones of local racial equality. An uncle, Prince Boston, was involved in the 1773 legal case that set in motion the end of slavery on Nantucket. When his daughter, Phebe Ann, was denied admission to Nantucket High School, Boston began litigation that spurred the desegregation of local schools in 1846.

|  | |

Left: Fig. 9: Spoilum (active ca. 1785–1810), Sampson Dyer, 1802. Oil on canvas; 23 x 18 in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of the Friends of the Nantucket Historical Association (2013.2.1). Right: Fig. 10: Prior-Hamblin School, Captain Absalom F. Boston, ca. 1835. Oil on board; 14½ x 10⅝ in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of Sampson D. Pompey (1906.56.1). | ||

| |

Fig. 11: J. Eastman Johnson (1824–1906), Captain Charles Myrick, 1879. Oil on panel, 29¼ x 25½ in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of F. S. Church (1895.14.1). |

When whaling on Nantucket declined in the 1840s and 1850s, islanders left for opportunities elsewhere, and the population plunged from 8,800 in 1850 to 3,200 in 1875. Those who remained returned to fishing, shepherding, and farming, and actively sought to reinvent the island as a resort for summer visitors. As early as the 1840s, islanders opened hotels tailored to tourists. Concerted efforts to advertise the island as a “watering place” in the late 1860s blossomed in a rush of hotel building in the 1870s. More tourist development followed in the 1880s, including a seasonal railroad to carry visitors to outlying beach hotels. The summer colony attracted the painter Eastman Johnson, who became the primary artist of national importance associated with Nantucket in the late nineteenth century. He and his wife began summering on the island in 1870 and returned annually through 1890. He painted numerous important genre scenes on island, and, in the 1880s, created portraits of island civic leaders and retired mariners. Johnson used Captain Charles Myrick (Fig. 11) as the subject of a number of paintings, capturing the spirit of an old captain confined to island retirement. In a particularly poignant study in the NHA collection, Johnson portrays Myrick in reflective decline, holding a Malacca cane with an ivory handle, once a symbol of fashionable elegance but now a sign of decrepitude, and wearing a beaver hat on his drooping head.

The island’s faded glory spoke to other artists as well, including Elizabeth Rebecca Coffin, the most important female artist associated with the island (Fig. 12). She was a student of Johan Philip Koelman, William Merritt Chase, and Thomas Eakins, whose realist approach is evident in her surviving works. Many of her works depict Nantucket scenes, often approaching the island and its people from a nostalgic point of view. In The Window Toward the Sea, Coffin portrays octogenarian Phebe Folger Pitman knitting by the window of her kitchen — the very image of quaint Nantucket that was a major selling point of the island as a summer destination in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

|

Fig. 12: Elizabeth Rebecca Coffin (1851–1930), The Window Toward the Sea, 1886. Oil on canvas; 25⅛ x 30¼ in. Nantucket Historical Association Collection; Gift of the artist (1902.2.1). |

A century and a half of promotion and development have transformed Nantucket from yesterday’s faded whaling port into today’s polished summer destination, underpinned by a multi-billion-dollar economy based on real estate, construction, and tourism. Nowadays, more than seventeen-thousand people live on island year-round — more than at the height of whaling. The Nantucket Historical Association seeks to be a voice for the island and its history, preserving and presenting the art and artifacts that illuminate this little island in the Atlantic.

Collecting Nantucket/Connecting the World: Nantucket Historical Association was on view at the Winter Show from January 18–22, 2019, Park Avenue Armory, 67th and Park, New York City.

|

For information, visit www.thewintershow.org or www.nha.org.

This article was originally published in the 2019 Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com.

Michael R. Harrison, at the time of publication, was the Obed Macy Director of Research and Collections at the Nantucket Historical Association, Nantucket, Mass.