Rooted Revived Reinvented: Basketry in America

Historically, baskets were rooted in local landscapes and shaped by cultural traditions (Fig. 1). They served utilitarian functions and played pivotal roles in stimulating identity and forging community (Fig. 2). The rise of the Industrial Revolution at the end of the nineteenth century led basket makers to create works for new audiences and markets, including tourists, collectors, and fine art museums (Fig. 3). While retaining the forms, iconographies, and processes central to their tradition, basket makers also responded to the regional availability of materials, cultural exchange, and market forces.

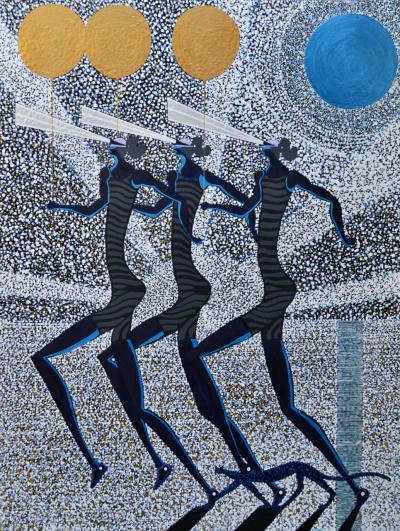

The “New Basketry,” an American art movement named by one of its founders, artist Ed Rossbach, emerged on the scene in the 1960s during an explosion of interest in all craft media (Fig. 4). Rossbach’s generous spirit inspired students and colleagues, who made California a hotbed of innovation that spread across the entire United States. These artists were influenced by a confluence of factors, including global weaving traditions, the back-to-the-landers’ creation of hand-made products, the feminist movement’s celebration of traditional crafts as art (Fig. 5), and experimentation with architecturally scaled textiles.

Today, there are three dominant strains in the contemporary basketry movement. Some artists perpetuate and transform the historical traditions in which they work. Responding to the growth of the art market, the loss of conventional materials caused by environmental devastation, and socio-economic issues facing their communities, these artists maintain basketry as living traditions (Figs. 6a, 6b). Other artists, inspired by the energy generated by the New Basketry, explore baskets as sculptural forms and experiment with new production methods and materials (Fig. 7 ). Their investigations, also motivated by modernism’s emphasis on the medium as the primary carrier of meaning, produce a visual language that interrogates American history and culture (Figs. 8, 9).

A third group of artists bridge the gap between the craft origins of basket making and the medium’s new place within sculpture, textile, and installation art. By exploring scale and dynamic form, these artists explore a wide variety of ideas and issues, including the visualization of scientific data, cultural appropriation and environmental politics. Additionally, they address the nature of art itself; how form and materials can be the subject of art as well as its meaning; and how art navigates between and among utility, commodity, and the aestheticized object in the fine art world (Fig. 10).

|

Fig. 1: Water bottle, Anonymous (Paiute), 19th century. Wood, mud, horsehair. Wrap-twined weaving, 21¼ x 13¼ inches. Lent by the University of Missouri Museum of Anthropology (RRR.62). |

Members of the Paiute tribe tightly wrapped and twined natural fibers into rounded forms and coated the exterior with mud to create vessels that stored and transported water. The two handles, made from horsehair, would have been attached to a braided strap that enabled women to carry the water bottles on their backs. The carefully engineered shape — with its short neck, rounded shoulder, and pointed foot — nestled into a carrier’s back and distributed the weight evenly, enabling her to carry several gallons of water.

|

Fig. 2: Lidded double-weave basket, Eva Queen Wolfe (Eastern Band Cherokee, 1922–2004), 1995. River cane. Double-woven diagonal plaiting, H. 9, W. 6½, D. 6½ in. Lent by Lambert G. Wilson (RRR.84 A&B). |

Wolfe learned weaving techniques from her mother and her aunt, Lottie Queen Stamper, who taught basket making at the Cherokee Indian School from 1937 to 1966. Wolfe focused on double-weave baskets with river cane so that the tradition “might be retained for future generations.” This technique was on the cusp of disappearing, in part because of the traumatic cultural upheaval that resulted from the Trail of Tears in 1838, when the U.S. Government forced the Cherokee to leave their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi River. Wolfe’s baskets, and those of contemporary artists working in the tradition she helped preserve, are nationally recognized as works of fine art.

|

Fig. 3: Rattle-top basket, Anonymous (Tlingit), ca. 1875. Spruce root, bear grass. Twining with overlaid imbrication. H. 3½ , W. 5, D. 5 in. Lent by Lois Russell (RRR.90 A&B). |

Traditionally, Tlingit rattle-top baskets were domestic workbaskets. Women wove a central chamber into the lid and placed loose pebbles or shot inside it, so that the basket made noise when it was moved. A pattern of repeated Raven’s tails (walhl-koo-woo) encircles the body of the basket, while spear barbs decorate its base as well as the lip of the lid. The once bright colors were created with synthetic dyes. At the end of the nineteenth century, rattle-top baskets like this one became popular tourist and collector’s items.

|

Fig. 4: Mickey Mouse coil basket, Ed Rossbach (1914–2002), 1975. Synthetic raffia, sea grass, coiling with imbrication. H. 6, W. 9, D. 9 in. Lent by Jim Harris (RRR.66). |

Translating traditional harvesting methods to modern life, Rossbach foraged readily available materials like plants and sticks as well as contemporary surplus such as foil, plastic bags, and newspapers for his work. He also appropriated pop culture iconography like his East Coast contemporary, Andy Warhol. This basket elevates the famous Disney character to the realm of fine art and critiques the low status given to craft media during this era.

|

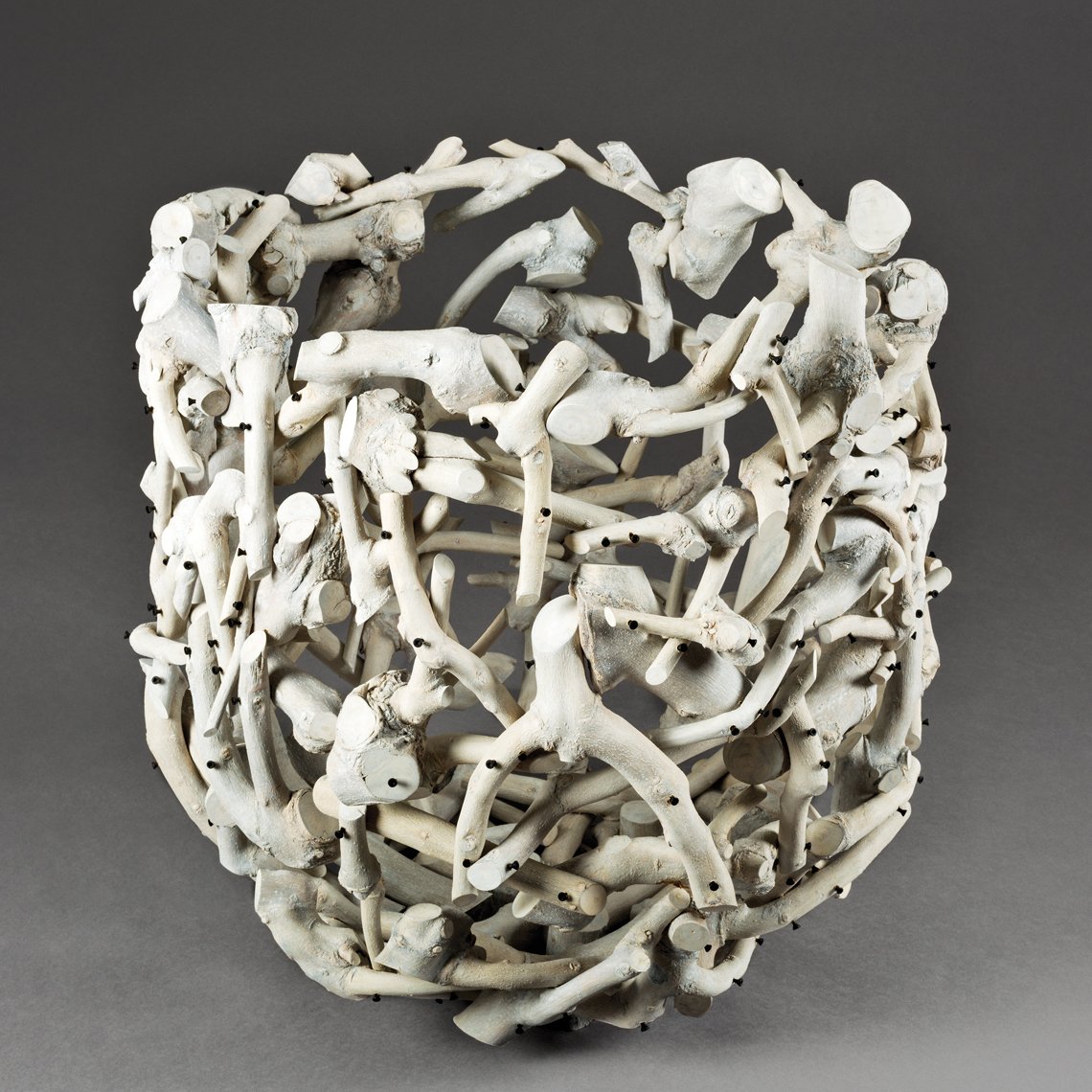

Fig. 5: Traverser, Gyöngy Laky (b. 1944), 2016. Branches, commercial wood, screws, acrylic paint. Fabrication. H. 24, W. 24, D 24 in. Lent by the artist (RRR.48). |

The latest in a series of works produced since the 1970s, Laky’s sculpture serves as a reflection on the history of basketry. She fabricated the vessel by sanding, painting, and drilling pieces of reclaimed wood and joining them with screws. The result is a “ghost” basket; its form evokes the utility of traditional baskets but its negative spaces deny functionality. The basket transcends time, marrying natural and industrial materials and the past with the contemporary world.

|

Figs. 6a, 6b: Yuppie Indian Couple, basket, Pat Courtney Gold (b. 1939), 2003. Acrylic yarn, Hungarian hemp. Twining. 9 x 7 inches. Lent by the artist (RRR.31). |

Gold revived the lost practices of Wasco basket making by studying traditional baskets and painstakingly transcribing their designs onto graph paper. This basket features a couple in two guises: on one side, they appear “Indian” according to the traditional iconography of native life; on the other, they flaunt the urban style they acquired after leaving the reservation, obtaining a college education, and accepting good paying jobs. The pairs are linked by a design that juxtaposes a historic Californian condor with a modern airplane, reinforcing Gold’s examination of the many elements, both traditional and contemporary, Native and non-Native, that fashion Indian identity.

|

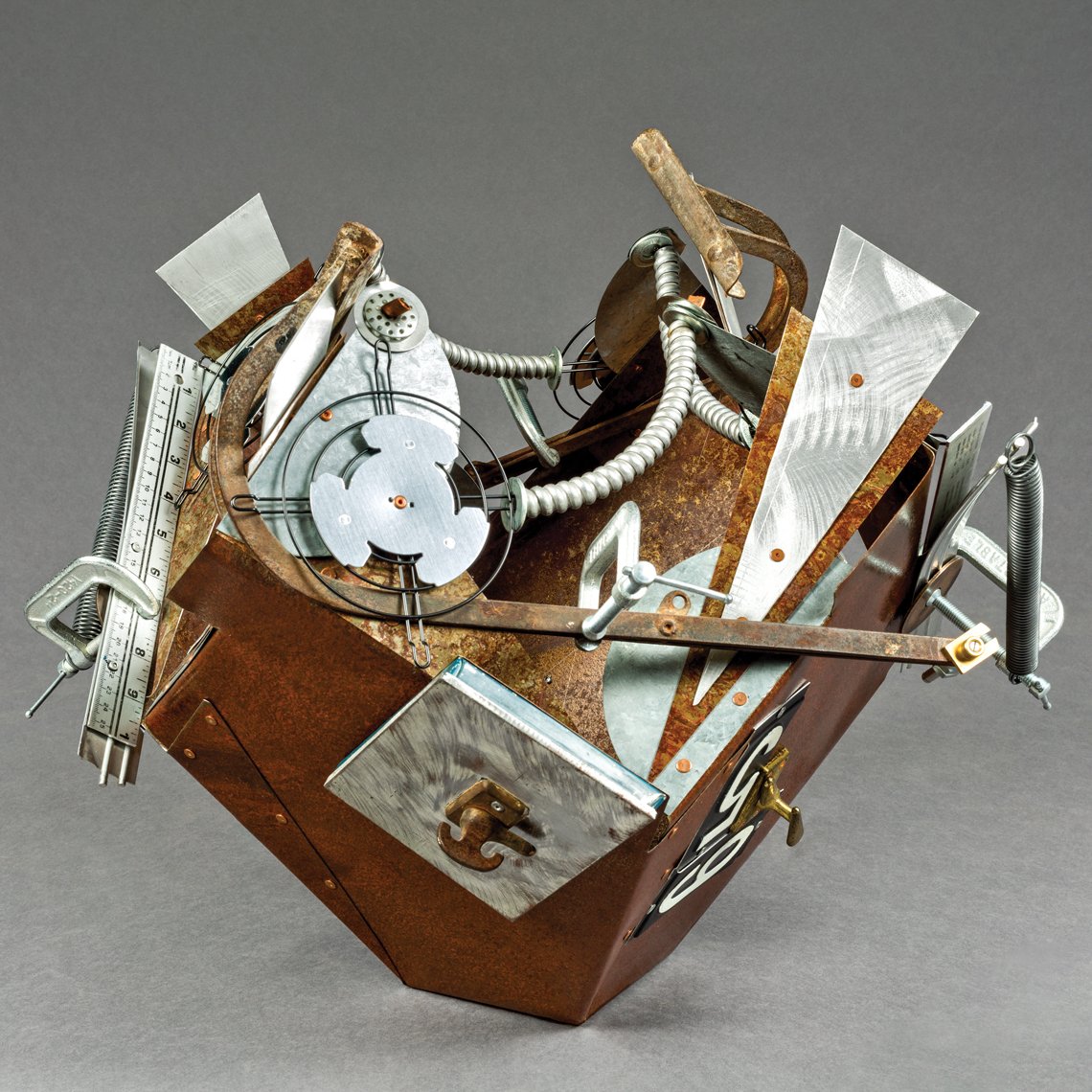

Fig. 7: The Builder’s Basket, basket, John G. Garrett (b. 1950), 1999. Oxidized steel, aluminum, miscellaneous metal findings, c-clamps, springs, partial yardstick, vintage steel skate components, aluminum louvers, metal cigarette boxes, house numbers, drawer pull, circuit board, metal mesh, electrical conduit, tin, copper tubing, fan covers, washers, nuts, latches, steel, copper rivets. Folded and riveted, Fabrication. H. 17¾ , W. 20, D. 21 in. Lent by the artist (RRR.2). |

Constructed in memory of his father, The Builder’s Basket includes materials Garrett collected while cleaning out the elder Garrett’s garage. As an electrician, his father accumulated a variety of mechanical objects that differed from the artifacts Garrett himself salvages from thrift and antique stores. By using materials found in his father’s workshop and collaging them into a form associated with his work, Garrett commemorates his father’s life through the “stuff” he left behind.

|

Fig. 8: Emery Cloth Bird, Leon Niehues (b. 1951), 2015. 3M emery cloth, white oak, brass and stainless-steel machine screws. Bent free-form, fabrication. H. 20, W. 12, D. 15 in. Lent by the artist (RRR.60). |

The gritty surface of the emery cloth skin is enclosed within a skeletal structure of white oak. Inverting inside and outside, it reveals the interdependence of natural and industrial production in contemporary life. Niehues harvests white oak on his forty-acre farm in northern Arkansas, using emery cloth — a 3M product — to sand the wood to a fine, smooth finish. Here, the emery cloth is more than a tool. It becomes a fine art material that forms the body of the bird, its presence made explicit by the brand label that appears inside the neck.

|

Fig. 9: They Were Called Kings, Shan Goshorn (Eastern Band Cherokee, 1957–2018), 2013. Watercolor paper, archival inks, acrylic paint. Plaiting. H. 13½, W. 8½, D. 7 in. Lent by the Shan Goshorn Family (RRR.34 A-C). |

Goshorn addresses the history of Native and Euro-American encounters in this series. Each piece presents a photograph of a contemporary member of the Warriors of the Anikituhwa — originally the first line of defense for the community and now ambassadors for the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation — wearing eighteenth-century-style clothing. The interweaving of past and present takes a narrative turn on the interior, which features printed accounts by Europeans of a 1762 visit of three Cherokee Warriors to England. Together, they show how European American representations of Native peoples, established over two hundred and fifty years ago, continue to dominate popular perceptions.

|

Fig.10: Work, Aron Fischer (b. 1980), 2014. Ebonized white oak, walnut, leather, synthetic reed, Egyptian paste, steel. Twining, fabrication. H. 24, W. 48, D. 4 in. Lent by the artist (RRR.26). |

Composed of a Shaker style peg board holding a series of handcrafted implements made from historical and contemporary materials, it appears, at first, to be a historic installation celebrating the Shaker ethos, “Put your hands to work and your hearts to God.” However, the actual utility of the tools remains a mystery. Fischer questions the very conception of handcraft by calling attention to the romanticism that surrounds it; even the Shakers employed industrial methods, like the assembly line and catalogue marketing, to meet the needs of consumers.

Rooted, Revived, Reinvented: Basketry in America has been traveling the U.S. since 2017. The exhibit is currently showing at the Briggs Museum of America Art, Dover, Del., through April 28, 2019. The show then travels to the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass., May 18–August 11, 2019; Ruth Funk Center for Textile Arts at Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Fla., September 21–December 14, 2019. For additional information visit the Fuller Craft Museum or americanbasketry.missouri.edu. The catalogue edited by Kristin Schwain and Jo Stealey is available through Schiffer Publishing Ltd. (www.schifferbooks.com).

Jo Stealey and Kristin Schwain, the School of Visual Studies, University of Missouri, are co-curators of the exhibit.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2019 edition of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com.