Winterthur Primer: Luxurious Lighting

|  | |

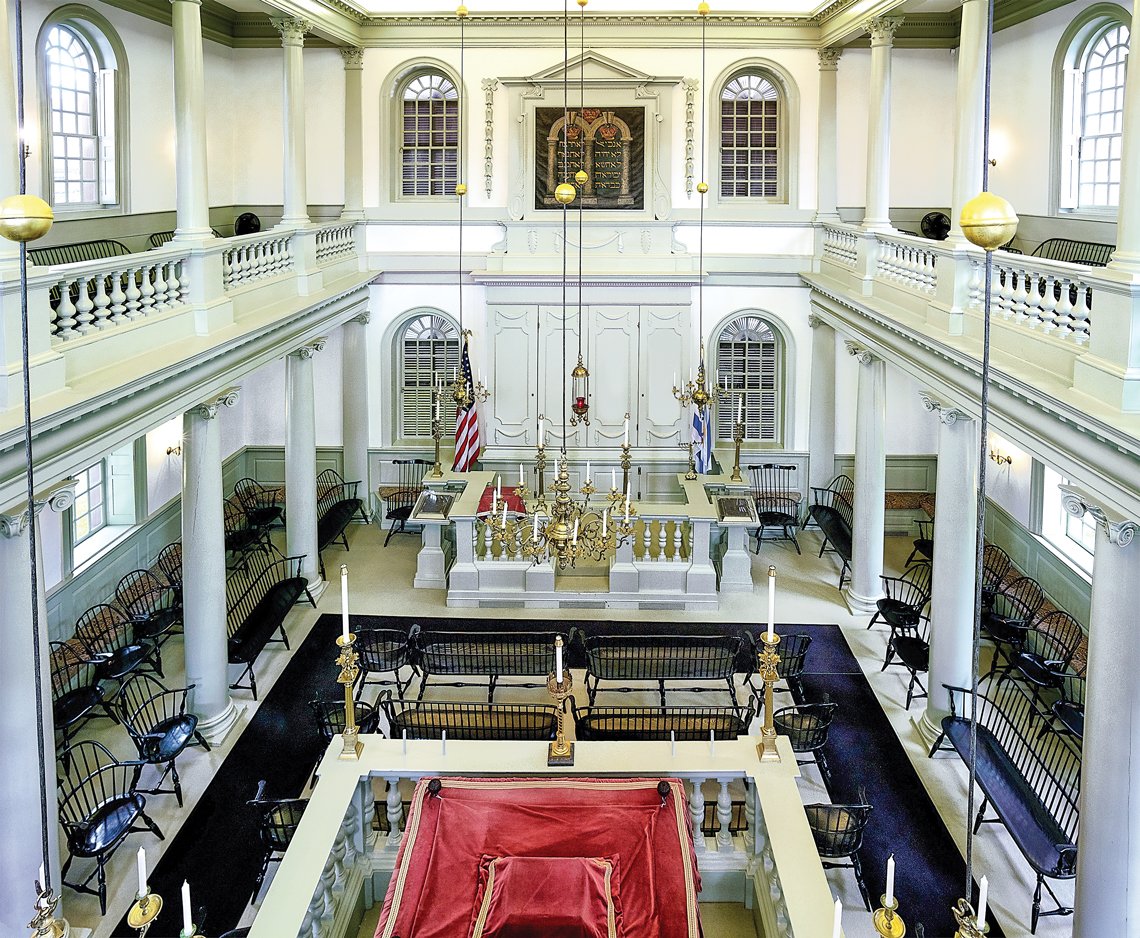

Left: Fig. 1: Touro Synagogue interior showing twelve-light chandelier (center), inscribed 1728, probably England. Brass. Courtesy: CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons (48760457). Right: Fig. 2: Ten-light chandelier in the State Closet, Chatsworth House, ca. 1694, England. Silver. Courtesy Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, England (DSC03230). | ||

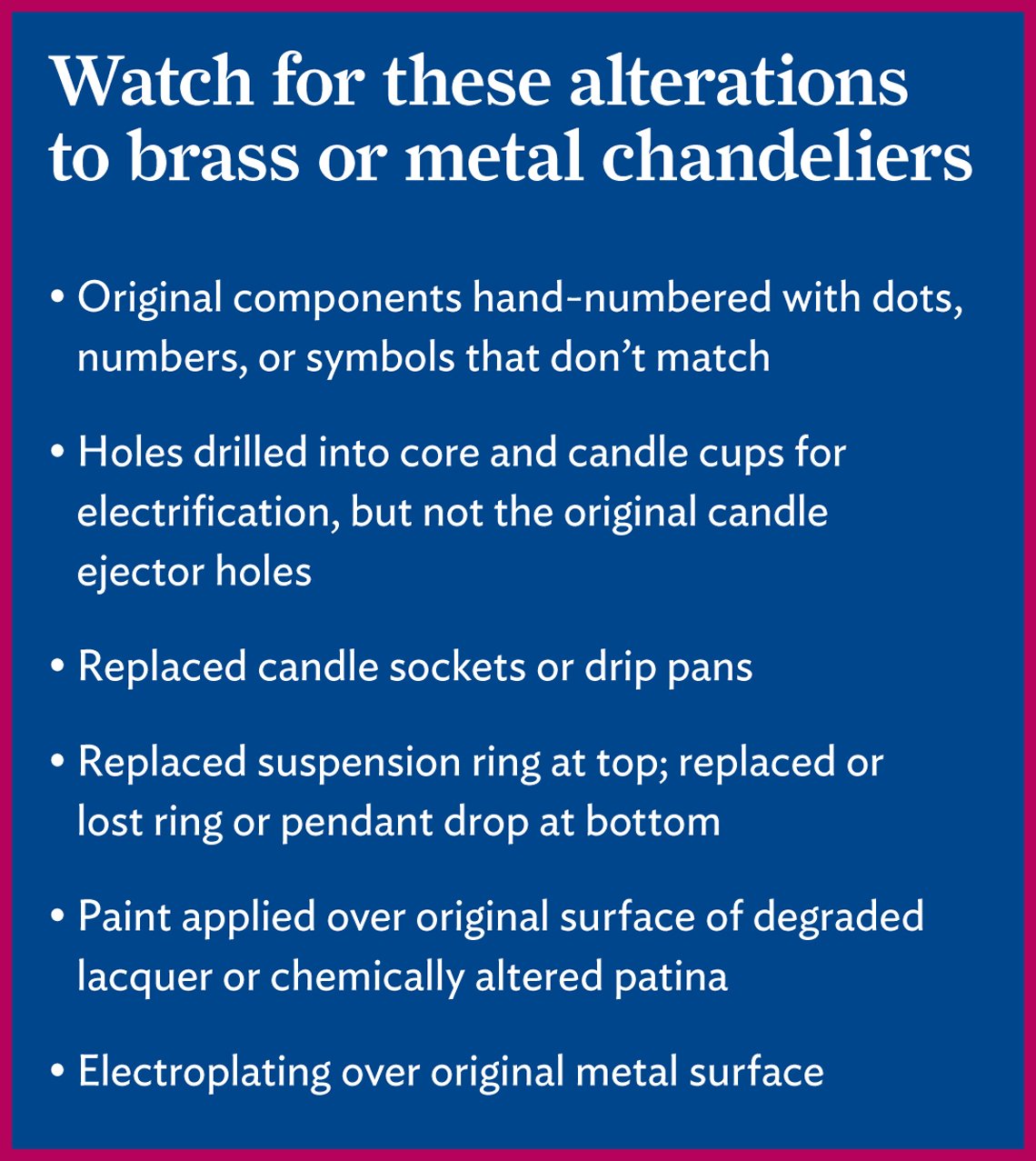

Within any collection or antiques saleroom, suspended chandeliers are uniformly difficult to inspect or maintain without risking a stiff neck or ladder ascent. As a result, they tend to hang around (pun intended), even if a room’s décor is updated. Alterations such as replacing a broken element or adding electrical sockets and wires inevitably occur over time, so a close visual inspection is warranted before acquiring an antique fixture.

|

Fig. 3: Twelve-light chandelier, dated 1742, attributed to Mark Fallon, Galway, Ireland. Silver, silverplate on brass, iron. Winterthur Museum, bequest of Henry Francis du Pont (1956.0519). |

| |

Fig. 4: Detail of figure 3 showing the lower sphere’s commemorative inscription for the Lynch family and the Dominican priory of Jesus, Mary and Joseph in Galway, Ireland. |

Remarkably, early chandeliers made in America or imported from Europe can still be seen in service in their original locations. Magnificent examples are the twelve-light brass chandelier at the Touro Synagogue in Newport, Rhode Island, from the early 1700s (Fig. 1); the enormous multi-tiered brass chandelier in St. Michael’s Church in Charleston, South Carolina, ordered in 1803, and the mid-1800s Cornelius and Baker gasolier in the Vermont State House. Provenance for multi-branched lighting fixtures made for domestic architecture is much harder to establish. Newer lighting technology and fashions prompted owners to replace them, releasing older chandeliers into the antiques market.

Solid silver chandeliers are exceptional in every category. Silver’s material properties hold desirable qualities similar to brass—reflectivity for candlelight as well as tensile strength and heat tolerance– but at a higher price. Unlike more humble lighting fixtures, their high intrinsic value generated documentation when ownership changed. In Europe, silver chandeliers illuminated chapels and churches, particularly in baroque Spain and its colonies, or in monarchs’ private spaces. An elaborate, ten-light chandelier acquired by the first Duke of Devonshire in the late seventeenth century for Chatsworth House still remains in the state apartments (Fig. 2). Early American newspapers mentioned silver chandeliers in relation to Europe; such extravagant fixtures appear only to have first arrived here with the collecting zeal of the twentieth century. 1

|

Winterthur Museum has approximately ninety historic chandeliers, primarily metal rather than glass or crystal, and almost all providing light for the house rooms and galleries. A stand out in the collection is the rare silver chandelier acquired at an auction in 1934 in New York (Figs. 3, 4). The delicate baroque chandelier is unusual in that its construction is primarily hammered rather than sandcast, with drawn and shaped graduated branches. There were additions, subtractions, and reinforcements to the candle cups and drip pans; several branches and the core spheres were not aligned, but its age and origin made it irresistible to the museum’s founder. The catalogue described it as Irish, dated 1742. Subsequent research determined it was made for a family named Lynch who donated it to the Dominican priory just outside Galway’s town walls. The donors were two sisters, Bridget and Ann Lynch, who became nuns in 1691. The funds for this commission may have been a legacy from their brother John, commemorated, along with his sisters, by the inscription on the lowest sphere. Or this possibly was the family’s patrimonial chandelier repurposed for the religious order’s chapel, where it remained until 1893.

When sold in New York many years later, the chandelier’s context of an ecclesiastical donation, Irish women’s silver patronage, and the history of many generations of use were nearly lost. Discovering meaning in the intangible elements of an object’s provenance can be as compelling as the visual evidence of manufacture, artistry, and alteration when collecting antiques, sometimes even more so.

1. The New-York Gazette’s noted that “six silver branches” from the Cathedral in Strasbourg were being melted at the royal mint (June 23, 1760). British silver chandeliers in American museums today include the ten-light chandelier marked by Daniel Garnier of London, England, ca. 1691–1697, acquired in 1938 by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and the eight-light chandelier designed by William Kent and marked by Balthasar Friedrich Behrens of Hanover, Germany, ca. 1736–1737, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, acquired in 1985.

|

This chandelier and other Irish American decorative arts from Winterthur Museum will be on view at the Delaware Antiques Show, November 8–10, 2019. For information, visit winterthur.org.

Ann Wagner is curator of decorative arts, Winterthur Museum Garden & Library.