Robert Duncanson: Painter of Freedom

|

Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), the Black artist of the Hudson River School, presents a challenge for scholars. His varied output—still lifes, genre, allegorical subjects, murals, and landscapes—presents a body of work yet to be fully deciphered. Guiding to a deeper interpretation are the extraordinary circumstances of a Black artist in the volatile 1850s, a fulcrum of experience forced between the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862. Recent discoveries of long-lost paintings by the artist, period literature and newspaper clippings, and maps and census data provide an eye-opener of context to Duncanson’s artistic journey. Applied to his art, this material reveals the hunger for freedom and basic human rights, all set in perilous but beautiful landscapes.

Robert Duncanson was born in 1821 to two free Black parents living in Fayette, New York, adjacent to the Seneca-Erie Canal extension project. After the opening of the canal, his family went west to Monroe, Michigan, where, when Duncanson came of age, he followed his father into the house painting trade. His interests lay in fine art, however, and he trained himself to paint still lifes and portraits from prints and drawings. A need to be in an environment where he would have more financial results caused Duncanson to move to Cincinnati, Ohio, which, because of its educated German immigrants and support of the arts, was referred to as the “Athens of the West.”

|

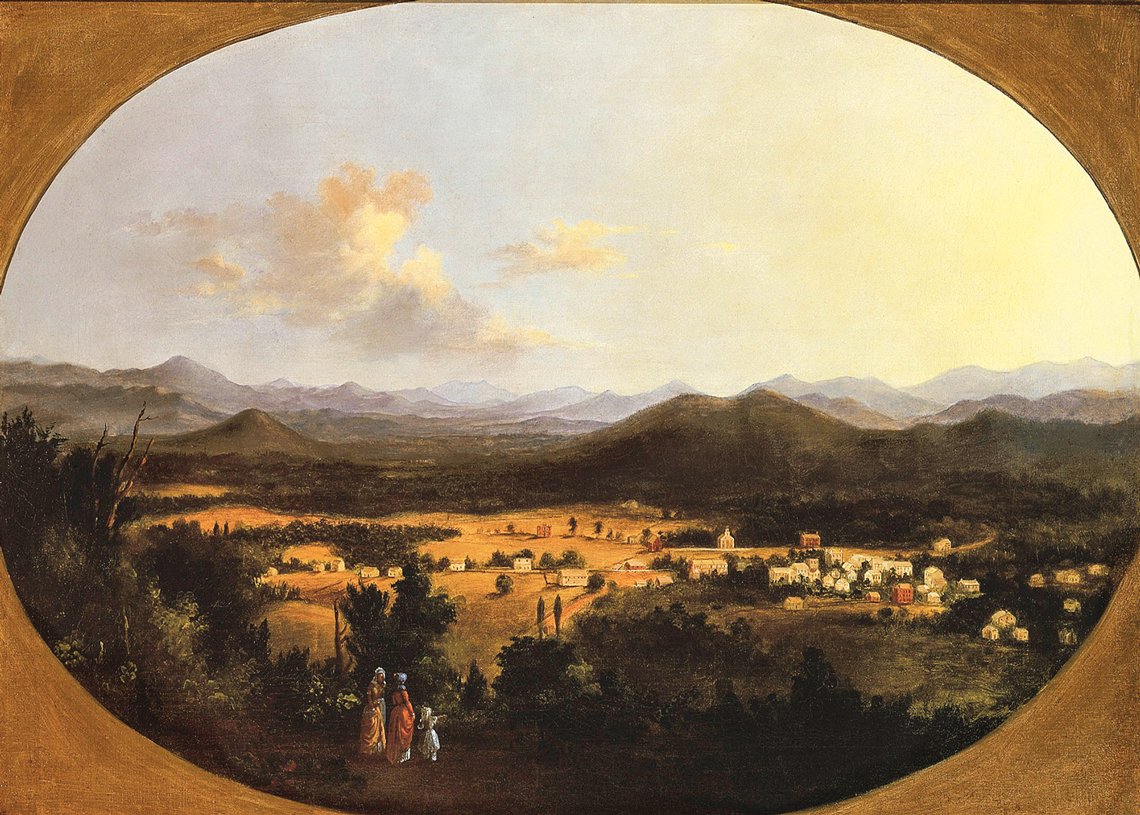

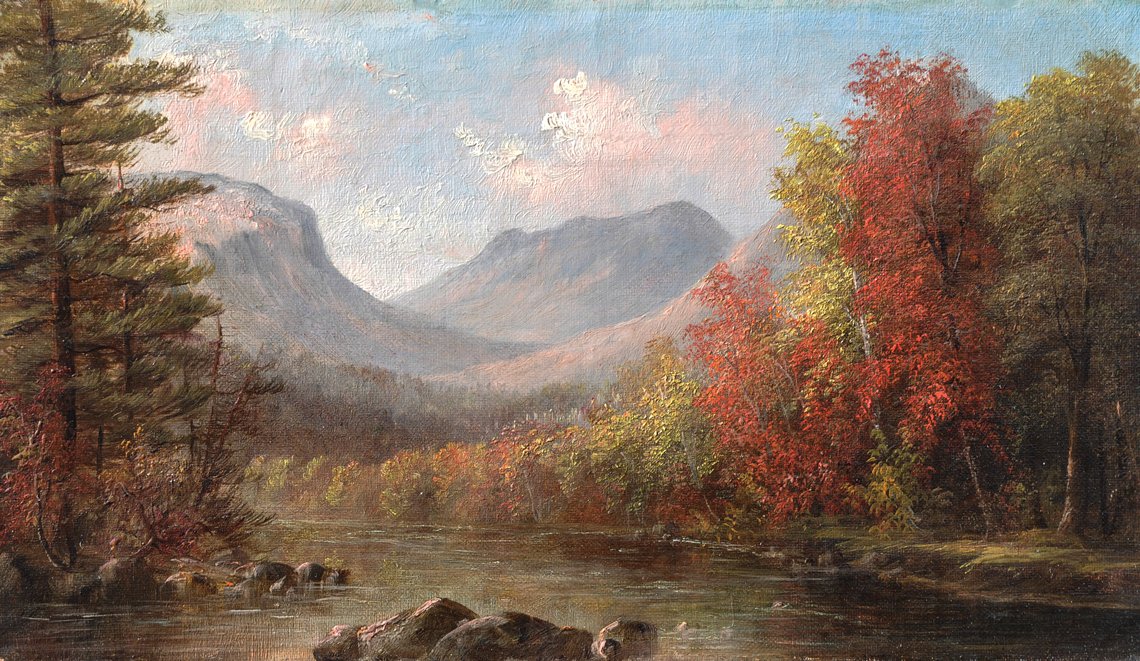

Fig. 1: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), View of Asheville, North Carolina, dated 1850. Inscription: (On back, underlining :) signed R. S. Duncanson. Oil on canvas, 23½ × 32½ inches. Greenville County Museum of Art (03.21.14). |

|

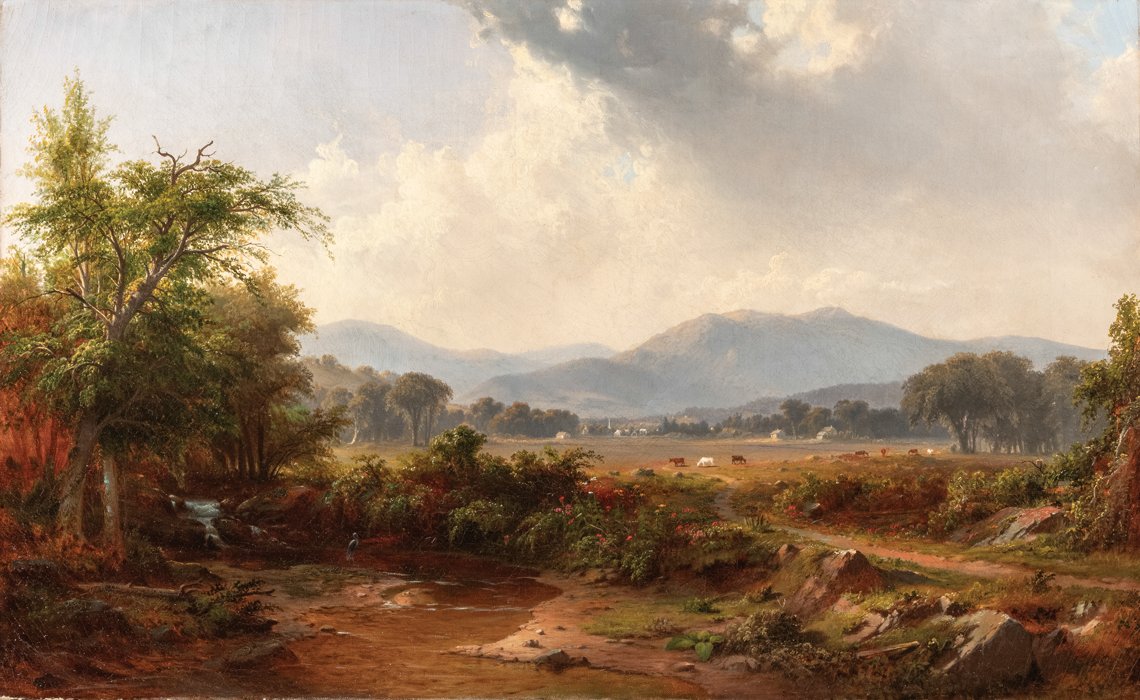

Fig. 2: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), A View of Asheville, North Carolina, 1850. Oil on academy board, panel: 13 × 18-13⁄16 inches. Museum purchase funded by the Susan Vaughan Foundation in memory of Susan Clayton McAshan. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Tx (2001.85). |

It was in Cincinnati, also a center for abolitionism, that Duncanson first painted landscapes and met and worked with one of the three major influences of his career, William Louis Sonntag (1822–1900), a central figure of the Hudson River School. Duncanson also studied the work of Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and Frederic Church (1826–1900), the latter whose path Duncanson may have crossed in 1860 when Church exhibited in Cincinnati. The influence of these three artists on Duncanson, whether directly or indirectly, starts to provide a timeline for Duncanson’s work, which can be broken down into three periods: Cole Influenced, 1848–1852; Sonntag influenced, 1852–1859; and Church influenced, 1860–1872.

During the past twenty years, a number of important Duncanson paintings have resurfaced at regional country auctions and the major sales in New York City. The subjects cluster in two areas: the Great Smokies of North Carolina/Tennessee (1850–1852) and the White Mountains of New England and in Canada (1860–1862).

The obstacles to reconstructing Duncanson’s travels to these regions, and why he did so, are enormous, especially in light of nineteenth-century logistics. Their common thread can be found in a previously overlooked Duncanson work of 1855, destroyed or lost, but explicitly detailed in a pamphlet titled Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade. As described, the canvas measured 600 yards in length, four yards in height, and incorporated fifty-three vignettes depicting Black slaves in flight to Canada from the Deep South.

|

Fig. 3: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), French Broad River, circa 18501–1851. Oil on canvas, 17 × 24 inches. Courtesy Private Collection, Bronxville, N.Y. Courtesy Private Collection, NY. |

|

Fig. 4: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), Landscape in the Smoky Mountains, Tennessee, 1851–1853. Oil on canvas, 16 × 26 inches. Courtesy Winterthur Museum; Museum purchase with funds drawn from the Centenary Fund, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum |

|

Fig. 5: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), Clinch Mountain, Tennessee. Oil on canvas, 16 × 26 inches. Private Collection, Yonkers, N.Y. Photo by Chris DeBow. |

|

Fig. 6: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Uncle Tom and Little Eva, 1853. Signed and dated lower left, “R.S. Duncanson 1853.” Oil on canvas, 27¼ × 38¼ inches. Detroit Institute of Art; Gift of Mrs. Jefferson Butler and Miss Grace R. Conover (49.498). |

| |

Fig. 7: Cover of Ball’s Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African American Slave Trade . . . Achilles Pugh, Printer (Cincinnati, 1855). |

Duncanson’s connection with the South—the first region under discussion—was through his first wife, Rebecca Graham, a freed slave from Nashville, Tennessee, who was living in Ohio, where, according to Hamilton County, Ohio, court clerk records, the two married on December 2, 1841. Nine years later the United States census of 1850 for Springfield Township, Ohio, described Rebecca Graham as age twenty-four, designated as an “M,” for mulatto. Her place of birth was identified as Tennessee. Two children with the last name of Dunkenson [sic] (ages six and four) were also listed as residing in the same household with Rebecca and her father, Reuben Graham, whose place of birth was identified as Virginia. The same census lists Reuben Graham as owning $14,000 worth of real estate, a remarkable sum for a Black American at the time. Of Robert Duncanson, no mention; the answer to his absence gets quickly answered.

In 2003, a previously unknown work by Duncanson of Asheville, North Carolina, dated 1850, surfaced at Brunk Auctions, also in Asheville (Fig. 1) Accompanying the painting was a period newspaper from the Asheville Messenger describing Duncanson’s trip to the vicinity in August of 1850. Until the newspaper clipping was found, no proof existed that Duncanson had ever set foot in North Carolina, though works exhibited by him in Cincinnati from 1850 to 1863 had titles invoking the state. The writers of the newspaper article mention that Duncanson had covered a great deal of territory:

Artists Mr. R. S Duncanson and A. O. Moore of Cincinnati, Ohio, have been at our village and vicinity of a fortnight and more, taking sketches of the mountains and river scenery. They have visited Warm Springs, French Broad, Black Mountain, Cumberland Gap, and Hickory Nut Gap. And have a number of correct sketches of the most interesting objects at these places. Mr. Duncanson appears to be a fine artist and has shown us a number of very pretty sketches. We hope he will be amply repaid for his trouble, and if he has them engraved, we have no doubt a large sale will be made of them. We wish him abundant success. Certainly, no part of America presents more, nor a greater variety of beautiful and grand scenery than Western Carolina and we are proud that artists are beginning to appreciate it. We are indebted to them for a very beautiful sketch of Hickory Nut Falls.

| |

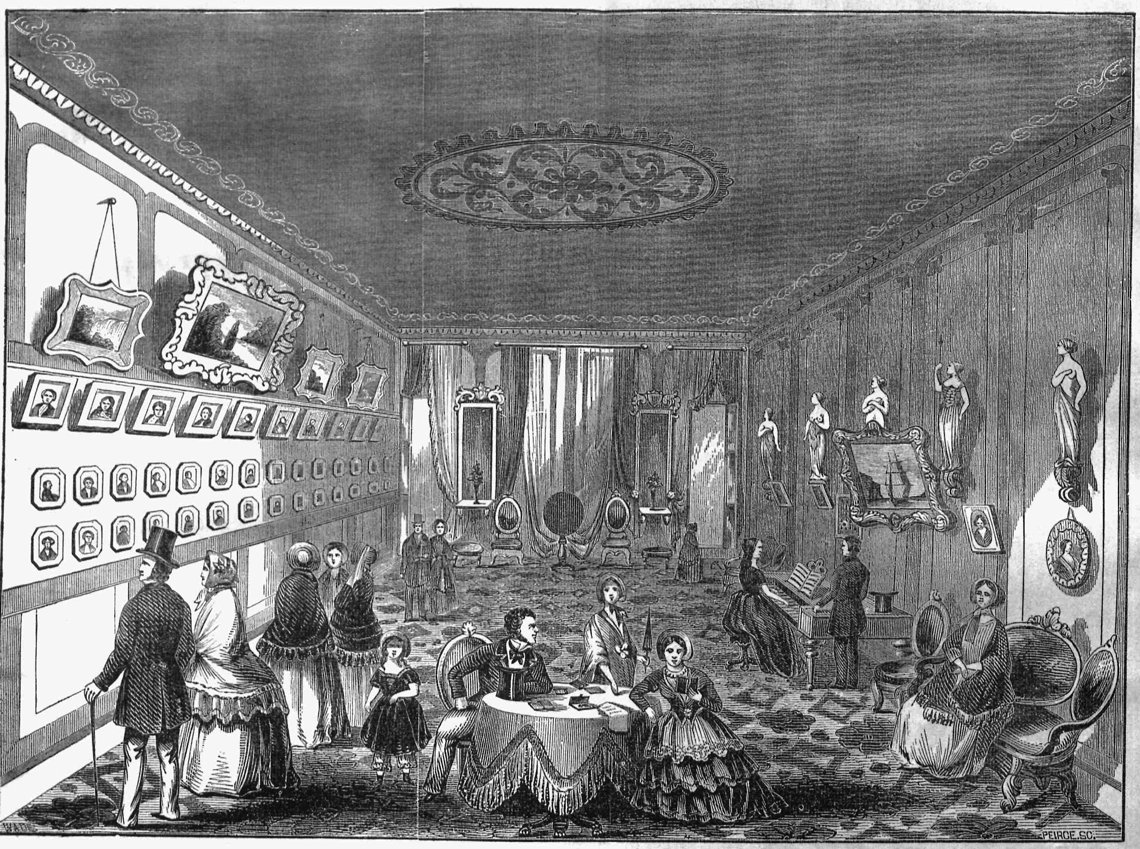

Fig. 8: Interior illustration from figure 7. |

The Asheville painting is a large panoramic composition view, derivative of Thomas Cole in terms of palette and brush. It is dark and dramatic, and somewhat loose in execution. The historic owner of the canvas prior to its sale was the Patton family of Asheville, and tradition held that it was executed for James W. Patton (1803–1861), who by 1860, was alleged to own seventy-eight slaves; he was one of the largest owners in the area. A smaller painting, similar in subject and date, belongs to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (Fig. 2). In that view, the town of Asheville is framed by gnarled and blasted trees trunks, clearly a devise borrowed from Thomas Cole’s Lake with Dead Trees (1825). The smaller work is believed to have descended in the family of Ernest Israel of Ashville before it arrived in the Museum of Fine Arts Houston collection in the early 2000s. It was a relative of Ernest Israel, named Jerry Israel, also of Asheville, North Carolina, who found the 1850 newspaper article. Jerry worked in the local newspaper business for many years before becoming an expert on the history of the Smokey Mountains as well as a partner in Brunk Auctions.

|

Fig. 9: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Landscape with Shepherd, dated 1852. Signed lower left, “R.S. Duncanson / 1852.” Oil on canvas, 32½ × 48¼ inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Purchase, Gift of Hanson K. Corning, by exchange, 1975 (1975.88). Duncanson titled this work Shepherd Boy. |

Duncanson’s companion on his southern trip was A. O. Moore, better known to history as Augustus Olcott Moore (1822–1865), an artist then publisher of books on horticulture, who was born in Augusta, Georgia. Duncanson likely met Moore through Cincinnati patron Nicholas Longworth (1784–1863), a wine merchant, horticulturist, and abolitionist. Moore and Longworth were active in Cincinnati horticultural circles, an interest that led to the Abolitionist Free Produce Association, a period alternative to buying produce from slave plantations.

Two locations visited by Duncanson and Moore were Warm Springs and the French Broad (River), both in the valleys on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee. Travelling up and down the Tennessee River, the largest tributary of the Ohio River, and by extension its remote Smokey Mountain tributaries, would explain how Duncanson and Moore accessed the area, since there were no railroads in that part of the country in 1850. In 2016, another work was brought to auction at The Potomack Company in Washington, D.C., a scene of the French Broad River, on the border of Tennessee and North Carolina (Fig. 3). Similar to the Asheville works, leaning trees bracket the romantic composition left and right; a Cole formula to give the illusion of depth. In the middle, birds flock together before heading north for the summer.

Resulting from that same 1850 trip to the western Smoky Mountains are two paintings, both 16 by 26 inches, possibly originally a pair. Rediscovered separately, one was exhibited in Cincinnati’s Western Art Union, in July 1851. This Eastern Tennessee work was cited in Cincinnati newspapers in the summer of 1851, less than eleven months after the Asheville trip, and described as follows: “Duncanson’s View on Clinch River, is a fine picture. It gives a view of the stream for some distance—of a plain on the opposite side, and of hills and mountains in the distance. The water has fine effects, and the distance is revealed as faithfully as in any picture we have seen by this artist, and his distance is good almost invariably.”

The first of these two canvases (Fig. 4), Landscape in the Smoky Mountains, Tennessee, was purchased by Winterthur in 2019. Exhaustive research by the late Duncanson expert Dr. Joseph Ketner, revealed a distinct Massachusetts provenance back to Clement Drew (1806–1889), an artist and an Abolitionist associate of William Lloyd Garrison, from Boston, Massachusetts. In the spring of 2018, the related example to the Winterthur work showed up in Massachusetts at the Cape Cod auction house Eldreds; it is now in a private collection (Fig. 5). Except for the degree of finish and locations of trees, they could very well have been based on the same eastern Tennessee landscape. When examined under infrared, the Winterthur example revealed that the stream and small waterfall were originally closer to the center, then moved toward the left, so at one time, these two works were even closer in composition. Winterthur conservator Matthew Cushman noted that pentimenti on the horizon of figure 4 reveal the mountains were changed and a soft mist added, consistent with the type of changes Duncanson often made.

|

Fig. 10: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Cattle and Rainbow, 1859. Oil on canvas, 30 × 52¼ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Leonard and Paula Granoff (1983.95.160). |

Some twenty works of North Carolina and Tennessee have now resurfaced, some of which display a crisper hand or finer draughtsmanship compared to Duncanson’s Cole-influenced earlier romantic vistas. This advancement in technique and use of multiple layers of pigment, and a known canvas in the collection of Walter Evans dated 1856, begs the question as to whether Duncanson returned south or simply revised earlier works in his studio after his European tour of 1853–1854, when he was exposed to the work of the Pre-Raphaelites in England? Though yet to be determined, it’s likely that Duncanson returned to North Carolina in 1856.

During the years 1850 to 1852, Duncanson was retained by Nicholas Longworth, previously noted, to produce what were referred to as the Belmont Mansion (now the Taft Museum) murals. Each mural was 110 inches tall, and anywhere from 77 to 91 inches wide, depending on the architectural space available. These landscapes were a challenge for a self-taught artist, who had no experience in executing large-scale compositions. Duncanson would put these new skills to use within a couple of years.

By the Spring of 1853, Duncanson had deliberately turned his back on the fleeting fame associated with his Harriet Beecher Stowe associated work, Uncle Tom and Little Eva (Fig. 6). By May 1853, Duncanson had departed for Europe on a grand tour to study the masters; he did so in the company of fellow Cincinnati artist William Louis Sonntag (1822–1900). According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, they left Ohio for New York in April of 1853, then took a ship to Europe. Duncanson and Sonntag returned to the United States via New York in January of 1854, and made it home to Cincinnati by May that same year.

| |

Fig. 11: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Lancaster, NH from Guild Hall, Vermont. Signed and dated 1862. Inscription on verso: “Lancaster, N.H./from Guild Hall/Vt./Painted/by R.S. Duncanson/Cin O 1862.” Oil on canvas, 20 × 16 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The John Axelrod Collection, Frank B. Bemis Fund, Charles H. Bayley Fund, and The Heritage Fund for a Diverse Collection (2011.1792). |

Once back in Cincinnati, Duncanson took up an association with James Presley Ball (1825–1904), a pioneering Black photographer who specialized in daguerreotype portraits chemically enhanced with color, presumably with pigments applied by Duncanson. The business was called Ball’s Daguerrean Gallery of the West. Aside from chemical portraits, the two collaborated to produce a canvas that measured six hundred yards long by four yards tall, titled Balls Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade (Figs. 7-8). This giant production was likely based on a series of engravings and/or daguerreotypes by Ball that were then projected onto the large canvas by a camera obscura or magic lantern process, one that helped Duncanson trace the basics of the composition, then fill in color and detail where needed. Of Duncanson, a reviewer remarked: “He is one of the most rapid painters I have met with; his largest works have been begun and finished in ten days, perhaps not at work on them only, but on others during the same time.”

The Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour was exhibited at the Ohio Mechanics Institute, Cincinnati, in March of 1855. In May of the same year, it traveled to Boston where it was on display at the Armory Hall on Washington and West Street, a venue for public speakers and art exhibitions. The original Pictorial Tour gets lost to history after Boston, but a digital copy of the fifty-eight-page pamphlet was found at the New York Public Library. Printed by Achilles Pugh (1805–1876), Cincinnati, 1855, the pamphlet explicitly details the slave trade—from the horrors of the Middle Passage and arrival in American ports such as Charleston, South Carolina, and New Orleans, Louisiana—to stories of escape by slaves bound for Canada. A sample of the fifty-plus remarkable stories portrayed by this pictorial includes: (#13) Interior of Banks Arcade; Auctioneers Selling Slaves (New Orleans auction and the fates that await); (#18) Mons. Valcoeurs Aimes Sugar Plantation; Growing Cane; Slaves at Work; #19) St. James Sugar Refinery. A Hunting Party on Horseback, with Dogs and Guns, in pursuit of runaways; #33) Mouth of the Big Miami; Railroad Bridge; and Fugitive Crossing the River on a Log.

Each of Duncanson’s scenes was likely twelve feet tall by thirty feet wide, based on there being fifty-three vignettes across 600 yards and four yards high. The climactic scene is titled, Queenston; Arrival of Fugitives on British Soil, which addresses the sad fate of Duncanson’s white Cincinnati neighbor, Seth Concklin, regarded as a martyr to the cause of freedom when he gave up his life to help escaped slave Peter Still, the older brother of Quaker William Still (1821–1902). William was the author of The Underground Railroad, A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c (1872), one of the published sources on the subject. Concklin was caught, branded with the marks SS for slave stealer, and then, wearing chains, battered and drowned in the Tennessee River.

Also exhibited in the Mammoth Pictorial Tour were six Duncanson landscape paintings. Foremost was Shepherd Boy (1852). It depicts a dark and dangerous landscape in which the shepherd guides a flock of sheep to safety (Fig. 9). Shown alongside Duncanson’s explicit depiction of slavery and the Underground Railroad, the shepherd is mostly likely a symbolic figure, possibly even an emblem of Concklin.

|

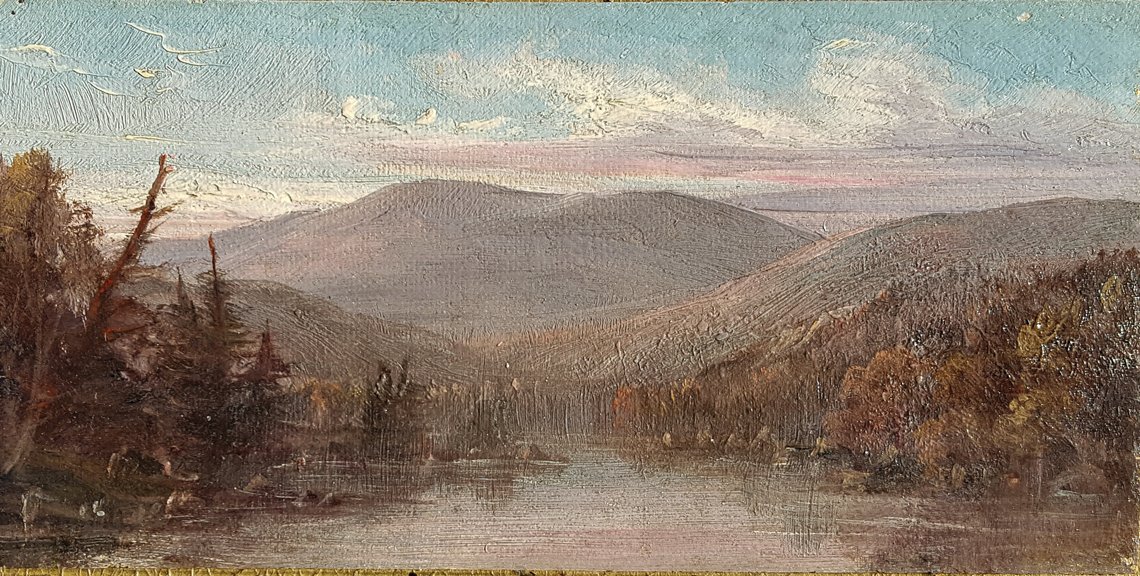

Fig. 12: Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872), Newport, Vermont, and Lake Memphremagog. Oil on board, 3 × 6 inches. Private collection, Yonkers, N.Y. |

Aiding the flight of a runaway slave was a criminal offense for which people could be prosecuted, or worse, as noted, depending on the jurisdiction. The net effect on Duncanson was that he had to be cryptic in his works, though it was obvious where his sympathies lay. The Splendid Mammoth Pictorial was as overt as Ball and Duncanson could get in their public support of the anti-slavery movement. Indeed, later writers on the subject such as Wilbur Siebert, author of The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (1899), wrote:

In view of the unlawful nature of Underground Railroad . . . that extremely little in the way of contemporaneous documents has descended to us even across the short span of a generation or two, and that there are few written data for the history of a movement that gave liberty to thousands of slaves. The legal restraints upon the rendering of aid to slaves bent on flight to Canada were, of course, ever present . . . There fore, written evidence of complicity was . . . avoided.

|

Fig. 13: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Presidential Range, White Mountains, N.H., circa 1861. Oil on canvas, 8 × 14 inches. Private Collection, Yonkers, N.Y. |

|

Fig. 14: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), Owl’s Head Mountain (Lake Memphremagog) Canada, 1864. Oil on canvas, 18 × 36 inches. National Gallery of Canada; Purchased in 1978 (18982). |

The Panic of 1857 brought the winds of change to the business. James Ball was booted out by Robert Harlan, a post-1855 investor, for “dishonest principles unbecoming any a gentleman,” which brought an end to Duncanson working with Ball. Occupied by more serious issues of freedom versus slavery, Duncanson’s response to the economic events was a sarcastic one, as noted in the Anti-Slavery Bugle of 1857:

“The Panic” we have panic goods, why not a panic picture? Duncanson is painting one. A bank director is represented with a “panic” on him. He is pale with hair steadily on end. Imps with sardonic grins attend to him.

In the fall of 1859, after the raid of John Brown on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had been put down, Duncanson completed Cattle and Rainbow (Fig. 10). The painting is a pastoral composition set beneath pinkish clouds, as cattle head to a rainbow by the river. According to William Still, the rainbow was associated with the escape of slaves across the Niagara River to Canada, a place Duncanson visited and painted for a scene in The Splendid Mammoth Pictorial. The Cattle were a symbol used in the “Grape-Vine telegraph code” for runaways.

The election of Lincoln coincided with Frederic Edwin Church’s painting The Heart of the Andes being put on display in Cincinnati at Pikes Opera House from late November 1860 to early January 1861. Advertisements by Church in the local papers encouraged people to view the masterpiece for a twenty-five cent admission fee. By late May of 1861, similar ads in Ohio papers exhorted readers to come to the same location to see “Duncanson’s celebrated picture The Land of the Lotus Eaters, on exhibition for a few days before going to Europe, Admission 25 cents, families and season tickets 50 cents.” Painted in the grand tradition of European historical works, Lotus Eaters is based on Tennyson’s poem about sailors from Odysseus’ fleet being seduced by temptation to remain in a false utopian world; Duncanson’s work, painted at the outset of the Civil War, was likely commentary on race relations and the South’s reliance on slavery.

|

Fig. 15: Robert Duncanson (1821–1872), View of Mount Orford, Canada, 1864. Oil on canvas, 31¼ x 52 inches. Signed and dated “Duncanson / 1864 (lower left) and “Mount Orford. / R. S. Duncanson. / 1864.” (reverse). Private Collection, on loan to the Minnesota Marine Art Museum. |

A likely impetus for Duncanson to leave for Europe was the ratification of the Corwin Act, by the state of Ohio on May 13, 1861, a proposed 13th amendment to the United States Constitution, passed by the Senate in hopes of derailing secession. The act would have made slavery permanent. Subsequent events rendered this moot, but, to Duncanson, the prospect of eternal slavery approved by his state of Ohio would have been alarming.

| |

Fig. 16: Map of the Stanstead Shefford and Chambly Rail Road And Its Connections, Published by Robertson & Seibert, 93 Fulton St., N.Y., 1858. This map illustrates the route of the Grand Trunk Railroad and the Stanstead spur line as well as locations where Duncanson worked that related to this right of way to Canada. |

In 1862, Duncanson exhibited Land of the Lotus Eaters in Toronto, Canada, then two years later in London, and Sweden, where it was purchased by King Charles XV of Sweden and Norway. In 1861 and 1862, prior to Duncanson’s move to Montreal, he made the first of several trips through New England, which point to the second group of works under discussion. A Duncanson canvas in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, titled, Lancaster, N.H. from Guild Hall, Vermont, (Fig. 11) is inscribed verso, Painted by R. S. Duncanson, Cin O 1862, meaning the artist painted the scene from a photograph or print in his Cincinnati studio, where he was at the time, a practice he was known to do. A seminal discovery ten years ago by Michael Meyer of a small oil on board, initialed “RSD” in the lower left, depicts Lake Memphremagog, Newport, Vermont, located on the border of Vermont and Canada (Fig. 12). With this image there were now two paintings of Vermont by Duncanson, eight hundred miles away from Cincinnati. Others were soon found. Meyer discovered two more works of autumn scenes in the White Mountains, the subject confirmed and described in a letter by the late Dr. Ketner of the Presidential Range of mountains in New Hampshire (Fig. 13), and another, of the nearby Saco River. A reference in the Cincinnati Daily Press, February 13, 1861, hints at such a trip when it described a small work by Duncanson titled The First Tints of Autumn. The composition included hills and bluffs, not the type of topographical detail found in southern Ohio, and likely the Presidential Range work.

With at least four images of northern New England now documented, the artist’s so called Canadian works deserved another look, namely Owl’s Head, in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada (Fig. 14), and an even larger work titled Mount Orford, bought by John Driscoll of Babcock Galleries in New York City at auction in 2005 (Fig. 15). Placed on a map, these six works wrap the border between Canada and northern New England, and follow the path of the Canadian railroad completed in 1858 (Fig. 16 ). The date proves that Duncanson would have travelled using the railroad. Known at the time as the Grand Trunk Railway, it ran from Portland, Maine, to Montreal, Canada, and eventually became the Canadian National Railway. Built so Montreal had winter access to the Atlantic, it primarily served to export Canadian lumber to the burgeoning industrial powerhouse of New England. And also, according to Wilbur Sibert in his encyclopedic book on the Underground Railroad (1898), it provided a ride to freedom: “The Grand Trunk, extending from Portland Maine through the northern parts of New Hampshire and Vermont into Canada, occasionally gave passes to fugitives, and would always take a reduced fare for this class of passengers.” These six works by Duncanson take on a new significance when it is seen that the locations are clustered around a railroad that helped enslaved fugitives make a dash for freedom.

1. Joseph Ketner, The Emergence of the African American Artist Robert S. Duncanson 1821–1872 (University of Missouri Press, 1994), 62.

2. New York Public Library.

3. The census details are confirmed in William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator (August 21, 1846).

4. Ashville Messenger, August, 14, 1850.

5. Robert Brunk, May We All Remember Well, A Journal of the History and Cultures of Western North Carolina (Asheville, NC: Brunk Auction Services, 1997), 117.

6. The river and location were identified by scholar Michael Meyer, who worked extensively with North Carolina historian Jerry Israel to better understand the topography of the Smokey Mountains.

7. Daily Cincinnati Gazette, July 2, 1851, “Western Art Union.”

8. Boston Globe, June 1, 1889, “Death of Artist Drew.”

9. Per conservation notes Cushman obtained from the Detroit Institute and the Cincinnati Art Museum, an institution that holds work by Duncanson.

10. Cincinnati Enquirer, April 15, 1853, “Trip to Europe,” 3. The work was commissioned by Reverend James Francis Conover, editor of The Detroit Tribune, whose position enabled widespread coverage of the canvas, including southern papers such as the Clarksville Jeffersonian, May 18, 1853.

11. Cincinnati Enquirer, May 6, 1854.

12. Clarksville Jeffersonian, May 18, 1853.

13. Ketner, 110–104.

14. Edward Radford, “Canadian Photographs,” Art Journal (London), n.s. Ill, (1864): 113.

15. Ball, Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade, 56. New York Public Library.

16. Wilbur Henry Siebert, The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (New York: Macmillan Co.,1898), 7.

17. Cincinnati Enquirer, December19, 1857.

18. Anti-Slavery Bugle (Lisbon, Ohio), November 21, 1857, “The Panic,” 3.

19. William Still, The Underground Rail Road, A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., (Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872), 760.

20. Siebert, Underground Railroad, 56.

21. Cincinnati Enquirer, September 20, 1869.

Robert Alexander Boyle specializes in works of the Hudson River School. A consultant for auction houses and writer, he has been involved in documentary film projects related to the topic and curated a show at Boscobel, in which Hudson River School paintings were exhibited next to his modern location photographs. The show traveled to the Sam Rayburn Gallery, U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C.

This article was originally published in the 21st Anniversary/Spring2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA has been rebranded and is now Incollect magazine.