The Arkansas Arts Center

Celebrating Fifty Years of Excellence in the Visual and Performing Arts

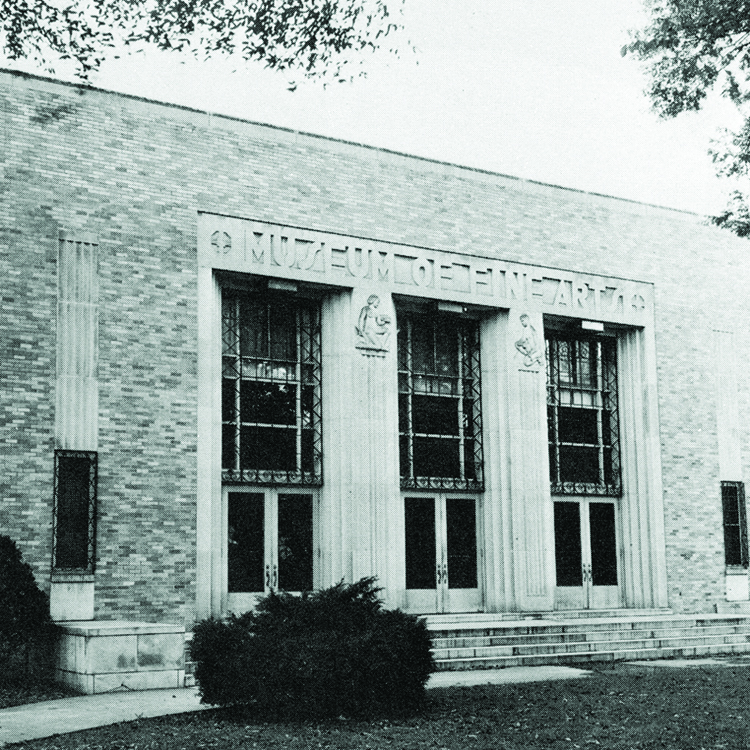

The Arkansas Arts Center (Fig. 1) is located in historic MacArthur Park in downtown Little Rock. The state’s premier center for the visual and performing arts, it was an outgrowth of the Museum of Fine Arts established in 1937 (Fig. 2), and opened its doors to visitors in 1963. During its past fifty years the Arts Center has organized a number of nationally recognized drawing- and craft-related exhibitions, including the biennial National Drawing Invitational (occurring this year), the National Craft Invitational (next occurring in 2015), as well as countless retrospective exhibitions of such artists as Will Barnet, Carroll Cloar, William Beckman, and Ron Meyers. The Arts Center is a dynamic facility, presenting classes in a variety of media for children and adults; offering live children’s theater productions; and possessing a world-class collection of art.

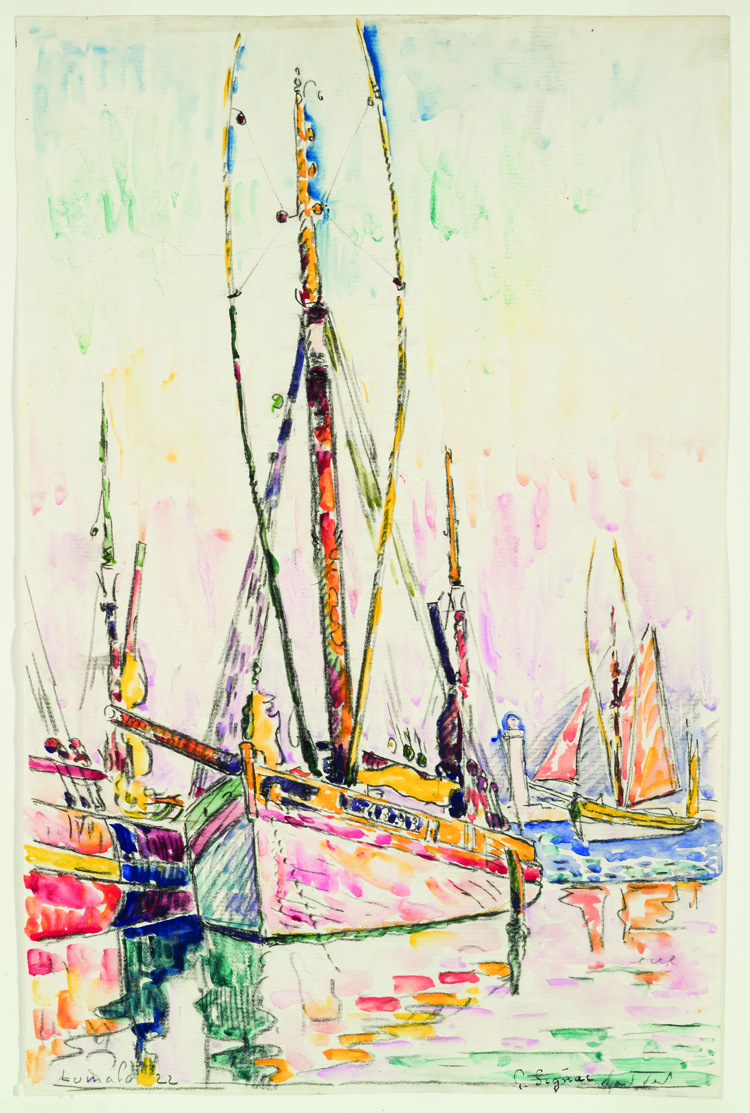

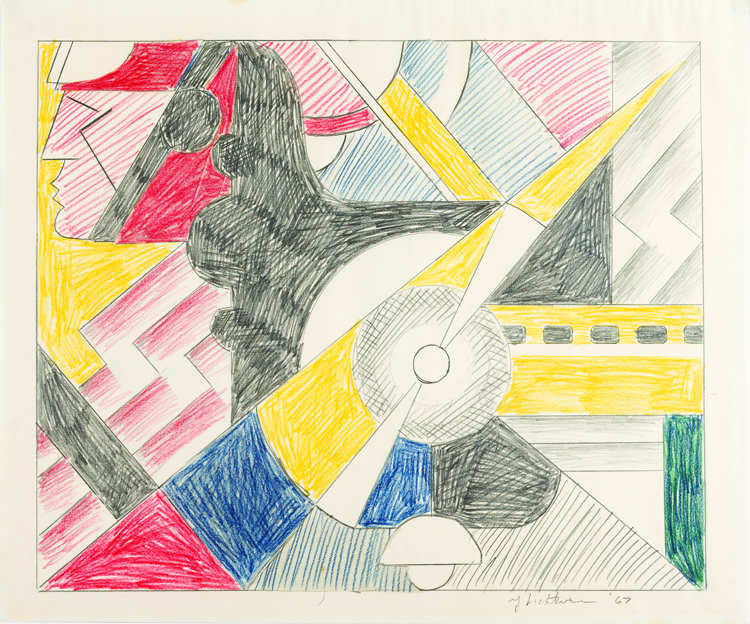

Throughout the last half-century, the Arts Center collection has grown to more than 22,000 objects and spans more than 600 years of artistic production. It began focusing its collecting activities in the areas of drawings and contemporary craft in 1971. In that year, the museum had made key purchases of drawings by Willem de Kooning, Morris Graves, and Andrew Wyeth; and the year prior, the museum had hosted the landmark traveling craft exhibition, Objects: USA. In the decades following, the museum has remained a leader in collecting and exhibiting artwork in these two areas, with notable strengths in French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism (Fig. 3), American Modernism (Fig. 4) and modern and contemporary (Figs. 5–12). The museum also possesses significant holdings from the earlier history of graphic art (Fig. 13), which help to convey the larger narratives of graphic art history.

This is one of the one-hundred-and-thirty-three watercolors and drawings by Signac in the museum’s collection, which is the largest and finest assemblage of Signac’s graphic art outside of France. The long poles of a tuna boat stand dramatically erect in Locmalo, thonier, one of Paul Signac’s masterpieces in the medium of watercolor. While the artist is most famous for his Neo-Impressionist oil paintings that use small dots of pure color to capture effects of light, he also created a great watercolor oeuvre. Beginning in 1892, Signac devoted an increasing amount of his artistic output to his new medium. Some of his most enchanting subjects were seen from the decks of his beloved yachts in waters all around France.

An exciting recent addition to the Arts Center’s drawings collection is a magnificent pastel drawing made by Georgia O’Keeffe in 1931, known previously only through a black and white 1931 photograph by the artist’s husband and dealer, Alfred Stieglitz. (Barbara Buhler Lynes, Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné, 1999, vol. II, 1106.) This drawing and a related oil painting, Shell on Red (private collection), were inspired by petrified shells that O’Keeffe had found during a summer sojourn in New Mexico. She said, “Out in those hills [near Taos] I picked up mussel shells in groups all turned to stone—probably millions of years old. They sometimes even had a little of the original blue color. I carried them back and left them somewhere in the unknown.” When O’Keeffe made these images she was moving from her famous flower paintings into her equally well-known images derived from the animal bones she brought home to New York from the desert. This drawing bridges the two series, combining the calcified shapes of bones with the sensual hues of flowers.

Rivera’s masterwork exemplifies his years in France before and during World War I, when he briefly but brilliantly embraced Cubism before turning to the stylized realism of his later years. In 1907 the young Mexican arrived in Europe on a grant from the Mexican government. Working first in Spain, where he painted more traditional compositions, Rivera had arrived in Paris by 1913, where he became captivated by the art of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and their fellow Cubists. Dos Mujeres demonstrates how Rivera’s Cubist paintings examine the world from multiple viewpoints. The faceted forms show the artist moving around people and objects as time passes. Dos Mujeres depicts a cluttered room in the Montparnasse district of Paris where the artist’s lover, the Russian artist Angelina Beloff, stands looking toward her seated friend, Alma Dolores Bastién. The dog lying beside the chair helps to evoke the relaxed atmosphere of this neighborhood, where creative young people gathered from around the world.

Roy Lichtenstein’s Study for “Aviation” illustrates some of the laborious processes that lay behind the artist’s production of his finished Pop paintings and prints; the Arkansas Arts Center collection includes many such preliminary drawings. Lichtenstein often began developing an image with a small colored pencil sketch that established the essential forms and colors. Next, he projected the drawing onto paper to enlarge it, as he may have done with Study for “Aviation.” Lichtenstein worked out many formal aspects of the composition in these mid-stage sketches, drawing and redrawing shapes to polish them. He altered some areas by drawing revisions on attached pieces of paper. Colors that appear in the drawing as roughly hatched areas of red and black are transformed in the final painting into either flat paint or the regular pattern of dots that the artist derived from commercial Ben-Day color screens. Lichtenstein’s 1967 painting Aviation (private collection), is about three times the size of this drawing and includes several changes in the composition.

Monumental drawings like John Himmelfarb’s Dos Guise are a specialty at the Arkansas Arts Center, in part due to the spacious galleries well suited to exhibiting big works. Himmelfarb’s intense linear style and rollicking approach to portraiture first arrived at the Arkansas Arts Center in 1988 as part of the second National Drawing Invitational exhibition. This series of exhibitions, which will have its twelfth iteration in 2014, brings to Arkansas the work of America’s most innovative and important graphic artists. Many artists featured in these shows later become important additions to the Arts Center’s permanent collection. A recent acquisition, Dos Guise is part of the Finch collection, a promised gift to the Arkansas Arts Center, which focuses on artists’ self-portraits that are truly individual. Himmelfarb’s Dos Guise, with its disconcertingly large scale and yet tight focus, and its vibrant pattern of lines, fills the bill perfectly. Himmelfarb’s witty title, a pun on disguise and two guys, is an added bonus.

Among the masterpieces in the craft collection of the Arkansas Arts Center is the monumental Vertical Sculpture—a gift of the Johnson Wax Company and exhibited at the Center in 1970 in the landmark craft exhibition, Objects: USA. Having first attended the Los Angeles Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design), in 1954, John Mason enrolled at the Chouinard Art Institute (now the California Institute of the Arts), where he became a student and a close friend of ceramist Peter Voulkos. The two rented a studio together in 1957, which they shared until Voulkos moved to Berkeley in the fall of 1958 to head the ceramics program at the University of California. Through Voulkos, Mason became exposed to the work of Abstract Expressionism and the artists of the New York School and became inspired to push the technical limits of the clay medium through his large-scale works and their firing. Nowhere is this more evident than in Mason’s early Vertical Sculptures. In their “rawness, spontaneity, and expressiveness,” writer Richard Marshall remarks, the sculptures “give the impression of having been formed by natural forces. The formal and technical aspects of balance, proportion, and stability—although purposefully planned and controlled—are subsumed by the very presence of the material itself.” (Ceramic Sculpture: Six Artists. Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981.)

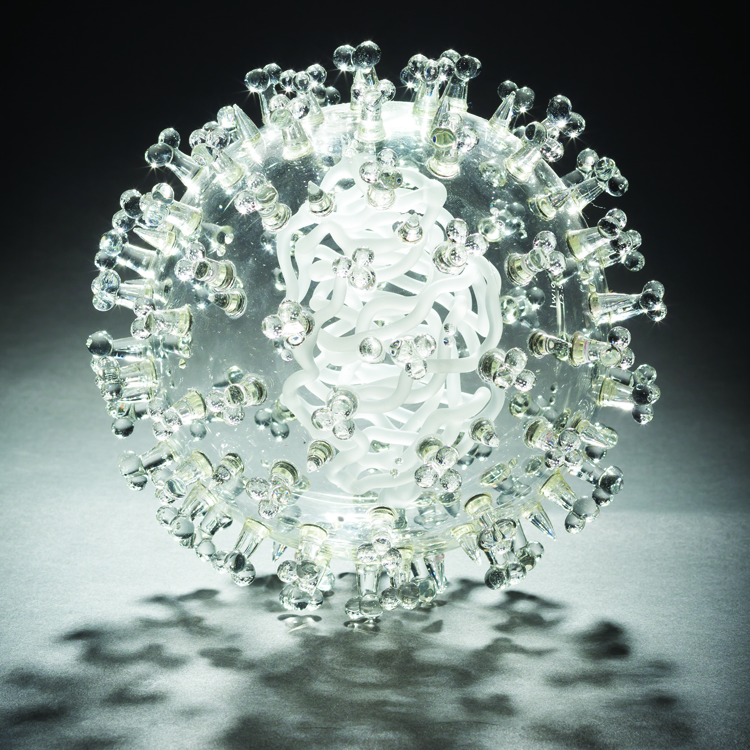

The blown- and flame-worked glass sculptures of Luke Jerram illustrate the ordered symmetry of the natural world—though on the microscopic level. An inventor, researcher, and amateur scientist, Jerram creates his transparent sculptures to call attention to the global impact of infectious diseases, to question the boundaries of human perception, and to further promote scientific understanding. Large SARS is one work from a larger series—Glass Microbiology—which the artist started in 2004 to raise awareness of the global impact of highly infectious diseases. The works in the series—others depict E. coli; Swine Flu; Ebola; HIV; Malaria; and others—are accurate representations of the colorless viruses (as they are smaller than the wavelength of visible light), rather than the artificially colored images disseminated by the media. By depicting the viruses in their colorless natural state, Jerram—who ironically is color-blind—establishes a paradoxical dynamic tension, whereby viewers admire a jewel-like sculpture that is both visually beautiful yet representative of something extremely deadly.

- Fig. 10: Gail Tremblay (American, born 1945)

And Then There’s the Business of Fancy Dancing…, 2011

Woven 35mm film; red, white and transparent leader film; metallic braid; plexiglas core, 25 inches x 14½ in. diam.

Arkansas Arts Center Foundation Collection: Purchase, Eleanor Herstein Wolff Fiber Arts Fund. Photo courtesy of Froelick Gallery

Through her unique basketry, Gail Tremblay explores the oftentimes contentious dynamic within intercultural and interpersonal relationships. Of Onondaga and Mi’kmaq descent, Tremblay is well-versed in traditional basketry forms and techniques, which she learned from her aunts, yet updates them for a contemporary audience through her use of film stock and film leader. In her recently acquired And Then There’s the Business of Fancy Dancing…—inspired by and made from stock of Sherman Alexie’s film, The Business of Fancydancing (2002)—Tremblay utilized contrasting red and white transparent leader film because “the central love relationship in the film is between a Spokane Indian man and a white man. I chose to use Porcupine Stitch because there are so many difficult and prickly relationships between characters in this film.”

Albert Paley has rightly earned his reputation as one of the nation’s foremost metalworkers. A master in a variety of forms and scales, ranging from intimate jewelry to functional objects to grand monumental sculpture, Paley’s versatile approach to forged steel and iron has pushed the limits of the medium and spurred a revival in the blacksmith’s art. Characterized by an organic style marked by a fluid linearity, Paley’s work is akin to drawing in three dimensions—and thus a natural fit to a museum collection rich in craft and drawing—and recalls the work of Art Nouveau masters, Hector Guimard and Louis Majorelle. In Plant Stand, Paley’s superbly crafted iron tendrils of varying thickness seemingly rise from the earth, reminiscent of wild-growing kudzu, wisteria or ivy, giving form to the stand and further emphasizing its function.

Born in Fort Smith, Arkansas, Robyn Horn is one of the leading contemporary artists in the state and the mid-South region. After exploring the media of glass, clay and paint, Horn turned to wood, which she felt afforded “the means of expression for which [she] had been searching.” Known for her abstract and geometric sculptures, she is drawn to their volume, form, textures, and negative spaces. She is obsessed with tension, movement, and the gestural qualities of sculptures. Nowhere is this more evident than in Pierced Geode, in which Horn skillfully reduces the burl, polishing its sides and a portion of the top while leaving some of its rough, natural state in stark contrast. Though a solid mass, the sculpture possesses both fluidity and grace, whose interplay of angles and planes create rich effects of light and shadow, enabling the sculpture to have fluidity, grace and even a sense of weightlessness.

With a few swift strokes of a pen, Rembrandt brought any story to life. Many of his drawings showed ordinary daily life in the Netherlands, but he also used his contemporary experience to add immediacy to biblical narratives. This drawing illustrates a dramatic moment in an Old Testament story from the Book of Kings. The central figure, Jeroboam, was a leader of Israel who set up golden idols for the people to worship. In this drawing, Rembrandt depicts King Jeroboam turning from his false idol to face a prophet who berates him. As the king extends his hand to harm the prophet, it miraculously withers. An accomplished draftsman, Rembrandt had difficulty in rendering the prophet’s hand. The artist often made corrections to drawings that he retained in his studio, either for his own use or the edification of his students. A drawing like this work therefore functioned as an independent work of art, although Rembrandt also drew preliminary designs for paintings and etchings.

With these firm foundations, the Arkansas Arts Center is well positioned to remain a vibrant cultural institution into the next half-century and beyond.

Brian J. Lang is chief curator and curator of contemporary craft and Ann Prentice Wagner, Ph.D. is curator of drawings

at the Arkansas Arts Center.

Photography by Cindy Momchilov, Camera Work, Inc., Little Rock, Arkansas, and are © Arkansas Arts Center.

This article was originally published in the 14th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is availale at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.