Master of Modern Silver: Erik Magnussen

Masterpieces Revealed

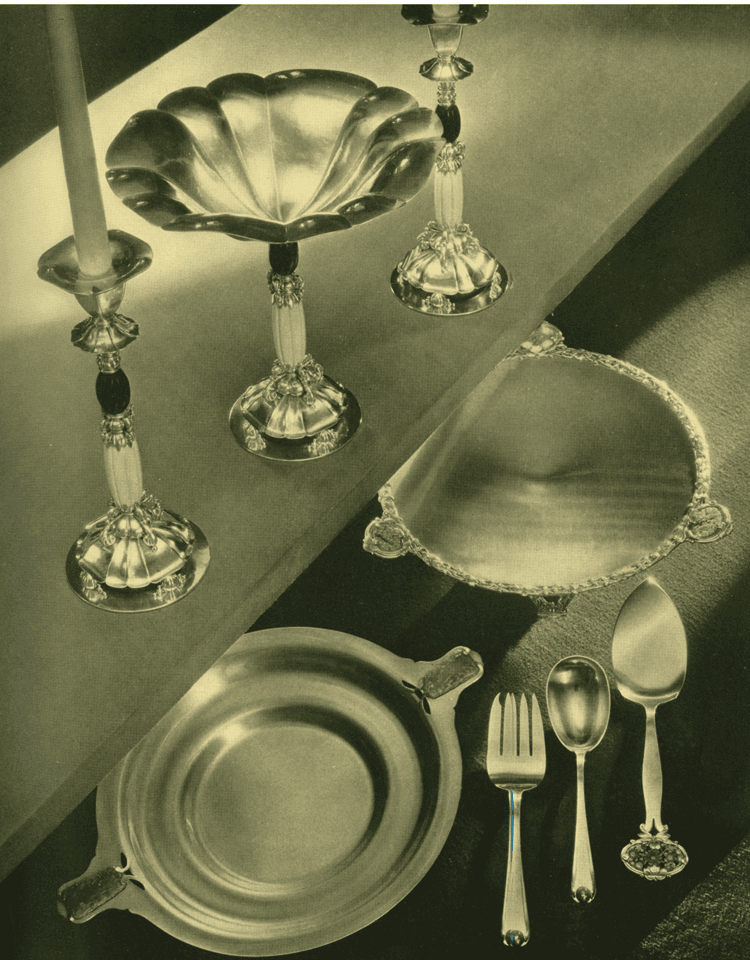

- Fig. 1: Console set, Erik Magnussen (1884–1961), designer, 1927. Sterling silver and ivory. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn. (compote) Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, by exchange (2002.34.1); (candlesticks) purchased with a gift from Jacqueline Lowe Fowler and the John P. Axelrod, B.A. 1968, Fund (2012.61.1.1-.2).

This archive article was originally published in the Summer 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

A Midwest auction in the spring of 2012 offering a pair of candlesticks by the émigré silversmith Erick Magnussen (1884–1961) presented the Yale University Art Gallery with a singular opportunity to complete a unique console set that he created in 1927 (Fig. 1).1 The compote from the set was purchased by the Art Gallery in 2002. This console set was heralded in its day for its exquisite craftsmanship and imaginative details. When Magnussen came to America in 1925 at age forty-one, it was with finely honed skills in metalsmithing and jewelry making. Although largely self-taught, he also had training in some of the leading workshops in his native Denmark and elsewhere in Europe. These skills are evident in both the design and execution of the compote and the candlesticks. Publicity about Magnussen in a March 1930 issue of Town and Country, noted that he had an international reputation, being “known in Berlin, Paris, and Rio de Janeiro.”

- Fig. 3: Cubic Coffee Service, Erik Magnussen (1884–1961), designer, Gorham Manufacturing Company American (1831–present), 1927. Silver with patinated and gilt decoration, ivory. Coffeepot: h. 9 1/2 in.; tray: 21 1/2 x 13 3/8 in. Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, The Gorham Collection, gift of Textron Inc. (1991.126.488).

From 1898 to 1901, Magnussen apprenticed at his uncle’s art gallery, Winkel and Magnussen, in Copenhagen, where he had his first exhibition in 1901. Also in Copenhagen he studied modeling with the Norwegian sculptor Stephan Sinding (1846–1922) and chasing with silversmith and sculptor Hans Christian Viggo Hansen (1859–1930). From 1907 to 1909 he worked as a chaser in the workshop of Otto Rohloff at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Berlin. In 1909 he returned to Copenhagen and opened his own shop after having sold his Grasshopper brooch to the Museum of Decorative Art in Copenhagen in 1907, a renowned piece of twentieth-century jewelry.2 Lacking the patronage to support himself as a silversmith, in 1912 he became the director of the department of arts and crafts at Bing and Gröndahl, where he designed porcelains decorated with gold and silver. In 1921 he worked for a period as a ceramist at the P. Ipsens Enke terra cotta factory, and in 1922, working in association with jeweler P. Hertz in Copenhagen, he took a grand prize at the International Exposition in Rio de Janeiro. Probably due to the faltering economy in Europe, in mid-life Magnussen came to the United States. When he arrived in New York on March 23, he identified himself as a sculptor, and was hired as a designer for Gorham Manufacturing Company in Providence, Rhode Island, where he had autonomous authority to create a line of modern tableware designs.3

Following the Paris Exposition of 1925, Americans with progressive taste were attracted to the styles of European modernism, and American manufacturers became acutely aware that they had no lines of modern designs to compete with European imports. Magnussen made a number of pieces in the latest European taste for Gorham, including works ornamented with semi-precious stones. One of his compotes evokes the work of the Parisian silversmith Jean Puiforçat in its use of radiating lines (Fig. 2).4 The Yale compote and candlesticks reveal the influence of Scandinavian design. As the metalwork scholar Peter Hinks has observed, “the decoration of beading and plump volutes is typical of Scandinavian arts and crafts,” and is readily observable in the work of the Danish silversmith Georg Jensen (1866–1935), who established a New York outlet in 1923.5 The carte blanche Magnussen had at Gorham to work independently in his own studio energized him to create the ultra deluxe console set. Shortly thereafter he channeled that energy and his innate ambition into a coffee service that brought modern art to American silver. The “Cubic” service, introduced by Gorham in November 1927 as “The Lights and Shadows of Manhattan” (Fig. 3), was a watershed moment for modern American design. Although Gorham promoted modernism with a coast-to-coast tour of the coffee service, its extreme styling found no Americans patronage even during the late 1920s boom economy. The service remained the property of the Gorham Manufacturing Company until it was given to the Museum of Art of the Rhode Island School of Design in 1991.

The Women Decorators’ Club in New York City became an important venue in 1928 and 1929 through which Magnusson’s silver was exhibited. In 1927, the Club, described as being founded “some years ago,” held its first public exhibition at the Grand Central Art Galleries of photographs of interiors designed by members, all of whom were women. In 1928 and 1929 the Club changed the character of its exhibition and displayed room settings. The “Lights and Shadows of Manhattan” appeared in a room setting by McBurney and Underwood in the 1928 Women Decorators’ Club exhibition at the Grand Central Art Galleries in New York City.6 In a further effort to develop taste for modern silver among Americans, Gorham also allowed Magnussen to produce special designs independently for distribution through the Women Decorators’ Club. As Helen Appleton Read reported in her Vogue review of contemporary silver, this venture was undertaken “in the belief that this organization would bring the right modern note before a clientele who would recognize its aesthetic merit.” Read illustrated a pair of compotes and a low bowl by Magnussen made for special distribution through the club.7 A compote like the one in Read’s illustration is marked “EM/STERLING/20/1927,” which indicates that the Magnussen silver made for special distribution through the Women Decorator’s Club does not have the Gorham marks (Fig. 4).8 On the pieces at Yale, the compote is marked “EM/STERLING/4/1927” and the candlesticks are marked “EM/STERLING/5/1927” (Fig. 5). The numerals “4” and “5” may be indicators that these pieces were Magnussen’s fourth and fifth independent projects that year.

When the Yale console set was made the form and its decoration were decidedly up-to-date. As Walter Rendell Story wrote in the New York Times in March 1928, “Console settings of sterling silver has become so popular that the usual three pieces—a pair of candlesticks and a bowl for flowers—have been developed by silverware designers so that almost any type of interior may have its appropriate ware.” In addition to the console set at Yale, Magnussen also made other ensembles of candlesticks and centerpiece bowls for Gorham in the 1920s.9 The sets often played off the luster of silver against the luxury materials of ivory, turquoise, and ebony. Magnussen also used carved ivory fluting for a series of covered compotes and candy dishes manufactured by Gorham in 1926.10 The ivory and ebony elements in the Yale compote and candlesticks also conform to the period’s taste for dramatic contrasts and highly accented design elements. Earlier in 1919, the song “That Black and White Baby of Mine,” by Cole Porter, satirized the celebrated interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe and the influence of her taste for black and white:

Now since my sweetheart Sal met Miss Elsie de Wolfe/The leading decorator of the nation/It’s left that gal with her mind simply full’f/Ideas on interior decoration. . . /. . . And she thinks black and white/She even drinks black and white/That black and white baby of mine.

Unlike Porter, Magnussen may have been celebrating “the first lady of interior decoration” by incorporating black and white materials in a set for exhibition at a club for women decorators.

The console set was slow to find a buyer. The candlesticks were exhibited by the Arden Studios at the Architectural League of New York in 1929, and later they and the compote appeared in a dramatic photograph by Sara Parsons in article an article by Augusta Owen Patterson in the March 1, 1930, issue of Town and Country (Fig. 6).11 Black Starr and Gorham, a leading retail outlet in New York City, is given as the source of the photograph, which indicates that three years after it was made, the console set was still for sale. The fact that the candlesticks are engraved “MKL,” but the compote bears neither a monogram nor an initial, and the oxidation differs on the ivory of all three pieces, suggests that the candlesticks went to one owner and the compote to another. The identities of these owners have yet to be established.

The history of the console set and the “Lights and Shadows of Manhattan” coffee service underscores the indifferent reception modern style silver received from mainstream Americans. The adverse economic climate that followed the market crash in October 1929 curtailed patronage for progressive styles in silver. Nevertheless, Magnussen found one enthusiastic client for his work—Marie-Louise Montgomery who became Mrs. James Osborn in 1929. In advance of her marriage, Marie-Louise shopped for objects to create a smart, modern home in which to live and raise her family. Although imported modern furnishings were available, she chose American-made objects in the modern vein, including silver by Magnussen. Her mother, Mrs. John F. Montgomery, provided funds for Marie-Louise to purchase a pair of candlesticks by Magnussen, although the particular Magnussen candlestick Marie-Louise purchased remains unknown. In writing to her mother in 1931 she expresses her great esteem for them, recounting how “the candlesticks make the room.” 12

Gorham’s efforts to introduce modern silver styles was commercially unsuccessful, and in 1929 Magnussen left the company to work for the New York branch of the German firm of August Dingeldein & Son. He opened a workshop in Chicago in 1932, and by 1934 was working in Los Angeles, after which he returned to Denmark in 1939.13 His legacy, however, are some of the most stunning and ambitious American silver objects in the deluxe modern mode.

Patricia E. Kane is the Friends of American Arts Curator of American Decorative Arts, Yale University Art Gallery.

The author acknowledges the assistance of W. Scott Braznell whose extensive files on Magnussen were invaluable in the preparation

of this article.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.

2. The brooch of silver, parcel gilt, amber and emeralds was illustrated in Time (September 20, 1982), 59.

3. Ancestry.com. New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.Year: 1925; Arrival; Microfilm Serial: T715; Microfilm Roll: 3625; Line: 15; Page Number: 21.

4. See, for example, the round silver serving dish in Françoise de Bonneville, Jean Puiforçat (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1986), 87.

5. Peter Hinks, “Metalwork,” in Gillian Naylor, et al., The Encyclopedia of Arts

and Crafts (New York: Dutton, 1989), 168. Also see, for example, Janet Drucker, Georg Jensen: A Tradition of Splendid Silver, rev. 2nd ed. (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2001), the ivory handle on the blossom teapot, p. 32, the floraform bases for bulbous sections of the candelabrum, p. 196, and the scrolls accented with shot on the candelabrum, p. 234, top of page.

6. “Interior Decoration at its Best: Four Rooms Assembled and Exhibited by the Decorators’ Club of New York,” Country Life (July 1928): 68.

7. Helen Appleton Read, “Twentieth-Century Decoration: The Modern Theme Finds a Distinctive Medium in American Silver,” Vogue 72 (July 1, 1928): 94, 98.

8. Sotheby’s, New York, November 21, 1981, lot 402.

9. See, for example, “Modern Silver Design: Erik Magnussen leads a Trend Toward Plainer Patterns,” Good Furniture 26 (June 1926): 291, fig. 1, and a set ornamented with turquoise that was exhibited at the 1929 Architectural and Allied Arts Exposition in Annual Report (Providence, R.I.: Gorham Manufacturing Company,1929); related candlesticks are illustrated in Charles H. Carpenter Jr., Gorham Silver, 1831–1981 (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1982), 262–63, fig. 281, and are now at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

10. Art Institute of Chicago, inv. no. 1984.1172; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, inv. no. 1999.254a-b; and Dallas Museum of Art, inv. no. 1990.230.A–B.

11. Augusta Owen Patterson, “The Decorative Arts,” Town and Country (June 1, 1929), 70.

12. John Adams to W. Scott Braznell, letter, May 8, 1981, citing notes from reading the Marie-Louise Osborn correspondence, then in the Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

13. In the 1930s Magnussen continued to exhibit in important exhibitions, see Illustrated Catalogue, Official Art Exhibition of the California Pacific International Exposition (San Diego, Calif.: The Palace of Fine Arts, 1935), part I, sup. 32; Contemporary Industrial and Handwrought Silver (Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum, 1937), n.p.; Silver: An Exhibition of Contemporary American Design by Manufacturers, Designers, and Craftsmen (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1937).