Modern Realism

The Sara Roby Foundation began collecting American art in the mid-1950s and over the next thirty years assembled a premier group of paintings and sculpture by the country’s leading figurative artists. A painter herself, Roby sought out art broadly defined as realist and artists concerned with the principles of form and design that she had learned as an art student, first in Philadelphia and later with Reginald Marsh and Kenneth Hayes Miller in New York. The resulting collection captures both the optimism and the apprehension of the years following World War II. Many of the works are poignantly human, others whimsical. Still others challenge us to decipher meanings embedded in complex, sometimes enigmatic scenes.

Sara Mary Barnes Roby was born in Pittsburgh in 1907. The daughter of a wealthy industrialist, she attended private schools in Philadelphia and was a student at Vassar College before beginning her art studies. Roby had a strong sense of social responsibility and wanted to help artists and educate the public, so she established a foundation “to foster, aid, and encourage in the United States of America the public appreciation, creation, enjoyment, and understanding of the visual arts.”

Championing realism was an assertive act at the moment when critics were celebrating abstract expressionism and promoting “action painting.” Roby refused to be bound by current trends, nor was she willing to be constrained by an orthodoxy of her own making. So, along with paintings by Edward Hopper, Paul Cadmus, and other contemporary realists, the foundation purchased abstract work by Stuart Davis, Louise Nevelson, and Mark Tobey. Roby and her advisors recognized that the beauty and spirituality as well as the tensions of modern life allowed for many kinds of realism. In 1959 an exhibition of the Foundation’s collection opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. It was the beginning of a twenty-five-year exhibition program that circulated the Foundation’s collection to museums throughout the country.

In 1937 Cadmus declared himself a satirical propagandist for the correction of moral evils. Possessing an acute eye for the telling glance, the inappropriate gesture, and the absurd expression, he adroitly caricatured individuals and social types alike. Night in Bologna is a provocative scene. A traveler with a suitcase seated at a café table observes a soldier in uniform, who looks toward a strolling woman. Each is bathed in a different color of light: the soldier in red for lust, the woman in yellow for greed, and the tourist in green for envy. The author once noted, “I leave out the mediocre, the in-betweens. I must select only the perfect petals, the most hellish.”

Will Barnet experimented with abstraction in the 1950s but in the early 1960s returned to the figure. Painting the human form, he said, allowed him to explore states of mind and human relationships. His foray into abstraction paid off in Sleeping Child. The linear simplicity of the feminine forms and softness of the gray-black palette speak to the universality of the bond between mother and child.

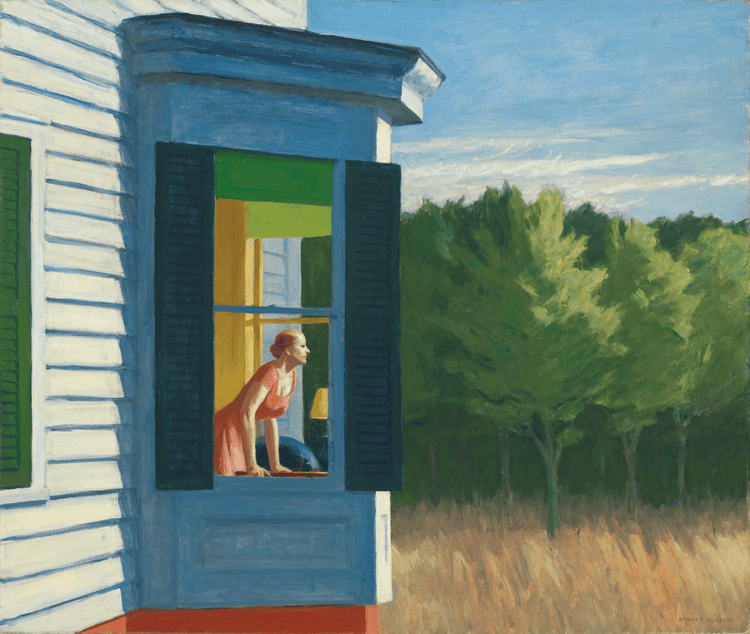

In Cape Cod Morning, a woman looks out a bay window, riveted by something beyond the pictorial space. She is framed by tall, dark shutters and the shaded façade of the oriel window. The brilliant sunlight on the side of the house contrasts with the blue sky, trees, and golden grass that fill the right half of the canvas. The painting tells no story; instead, the woman’s tense pose creates a sense of anxious anticipation, and the bifurcated image implies a dichotomy between her interior space and the world beyond.

Charles Burchfield used landscape forms as symbols to convey dreams, memories, and reminiscences of childhood. Night of the Equinox captures a violent storm in the backyard of his parents’ home in Salem, Ohio. Here, driving rain pours from ominous clouds, and fantastical trees dance in the electrified air. The artist remembered the experience as “One of the most exciting weather events of the whole year. What we called the spring equinoctial storm. It seemed as if terrific forces were abroad in the land.”

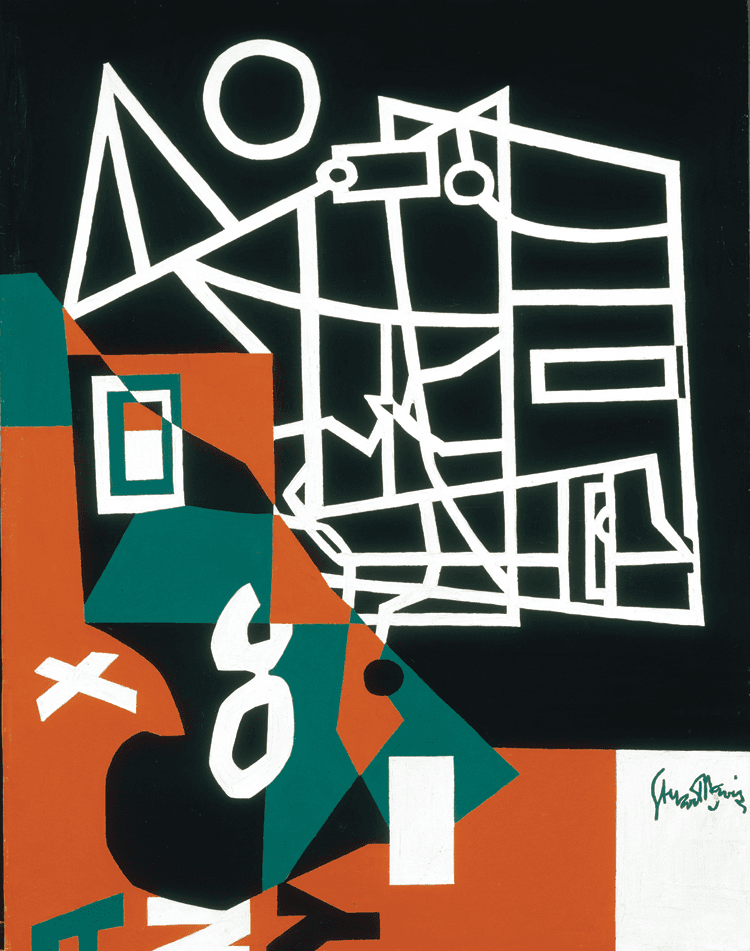

Although working with abstracted forms, Stuart Davis considered himself a realist and devised an artistic shorthand for this “memo” about Gloucester Harbor. Ship masts and wharf structures are schematically suggested by intersecting white lines below a white circle that floats like the moon against a night sky. The foreground is a tangle of overlapping red and green planes punctuated by letters and numbers. The word “any” at the bottom left refers to Davis’s belief that any subject can be transformed into art; the number eight, his reference to infinity.

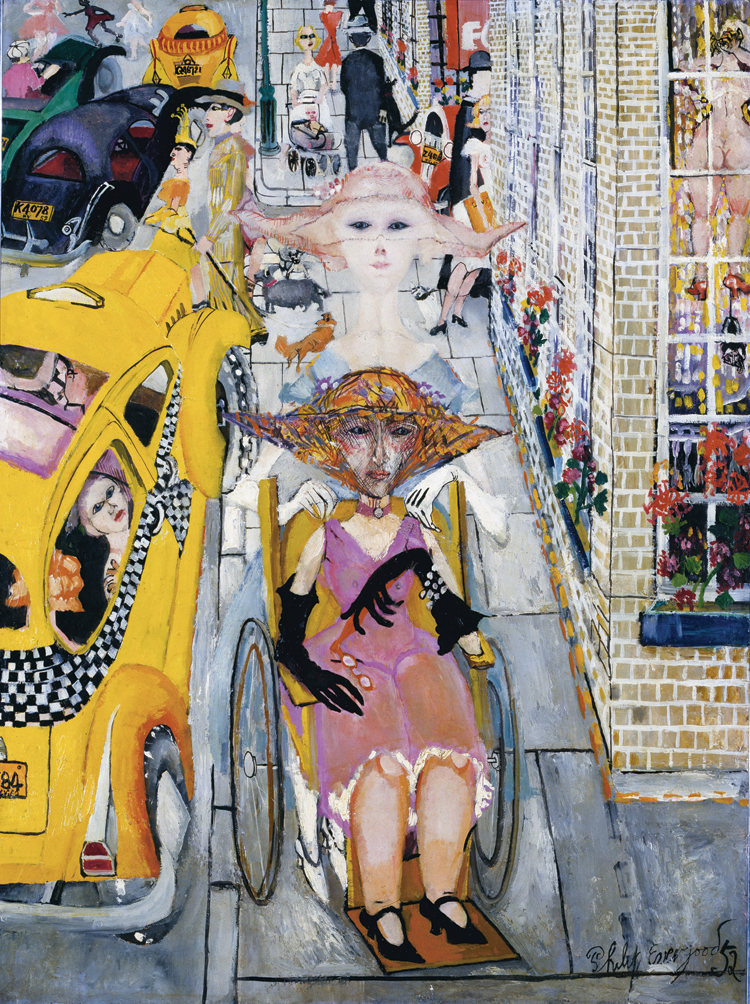

Evergood’s art reflected a deep commitment to social equality and sympathy for human frailty. Recollecting the genesis of Dowager in a Wheelchair, he wrote, “Once I saw a tragic old lady being wheeled on Madison Avenue. She was alive in spirit but her body was only half functioning. She wanted still to be young. A young, gentle, fascinatingly fresh companion was wheeling her. As I passed, spring was in the air, a delicate whiff of lilac perfume mixed with a faint background of crushed rose petals reached my nostrils & then my brain. I was disturbed. I stopped when they’d passed and followed their progress through the crowds with my eyes. Taxis & cars were too noisy. I lost sight of them in a few moments. I went sadly on my way with a vivid memory which lingered on. I consider the painting to be one of the very best I ever painted.”

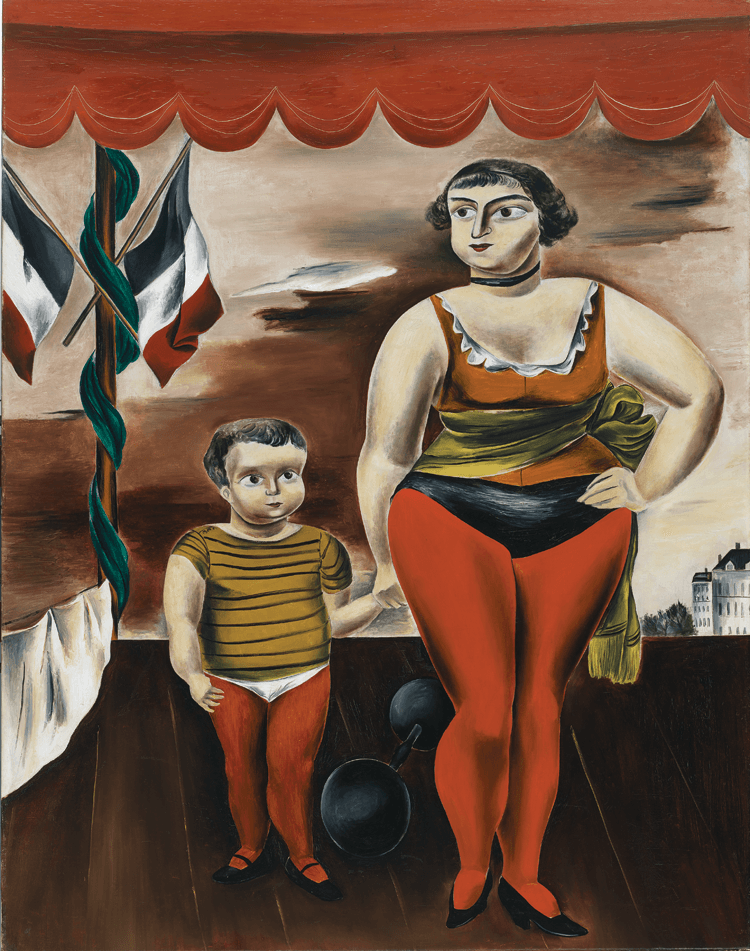

Kuniyoshi’s paintings often encoded his experience as a Japanese immigrant in the United States, where in the 1920s anti-Asian discrimination was pervasive, and restrictive immigration laws prevented him from becoming a citizen. (His wife, Katherine Schmidt, was disowned by her wealthy family when they married.) He painted Strong Woman and Child while in Paris, where the liberal environment and friendships with other artists, among them Alexander Calder, provided a sense of freedom and emotional support. The strong woman of the title is a circus performer who stands on a stage, French flags entwined at the backdrop. The mother figure, who may be a stand-in for Katherine, affirms her protective relationship with the child, who seems perhaps a symbolic portrayal of the artist himself.

During the forty years Kenneth Hayes Miller taught at the Art Students League in New York City, he encouraged a generation of American painters, including Reginald Marsh, Paul Cadmus, and Sara Roby, to find inspiration in contemporary life. Yet he also counseled compositional balance and the value of classic form. For his own work, Miller looked to the shoppers, salesgirls, strollers, and streetwalkers he encountered around Fourteenth Street and Union Square. In Bargain Hunters, he captured the crush of femininity on sale day. Although the women seem frozen in space, their eyes sparkle with the excitement of bargain hunting.

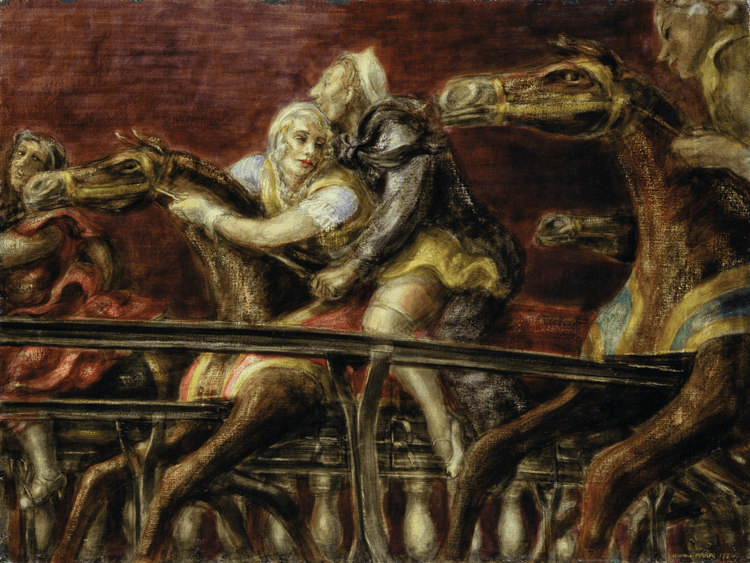

Marsh captured the gritty side of life in New York City and Coney Island. His subjects were often crowded together in the turmoil of humanity; his powerful emotive renderings providing audiences with palpable connections to those within the scenes. Captivated by the lure of women, Marsh’s work was often heavily sexualized, with women depicted as strong, but also vulnerable figures. Steeplechase Park was one of three amusement parks at Coney Island in Brooklyn. Here, Marsh shows a couple astride one of the mechanical horses that raced around the Pavilion of Fun on iron rails that, in places, were as high as thirty-five feet above the ground. The nested bodies of the sailor and girl exude the passion of young love, although the strained expression on the woman’s face may signal the transience of their affection.

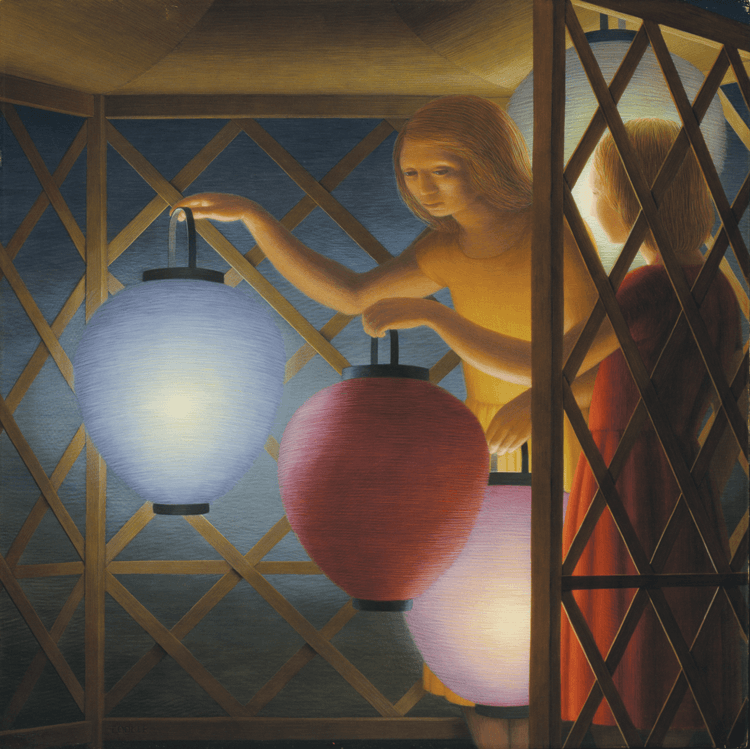

Like his friends Paul Cadmus and Bernard Perlin, Tooker painted in egg tempera. In the Summerhouse shows two young women surrounded by a lattice framework. The Japanese lanterns they hold cast a warm light on their arms and faces, illustrative of Tooker’s luminous imagery for which he is known. The nocturnal scene is gentle, the serene enclosure a refuge from the night. His narrative technique creates an evocative intimacy between the figures, welcoming the viewer to participate in their experience.

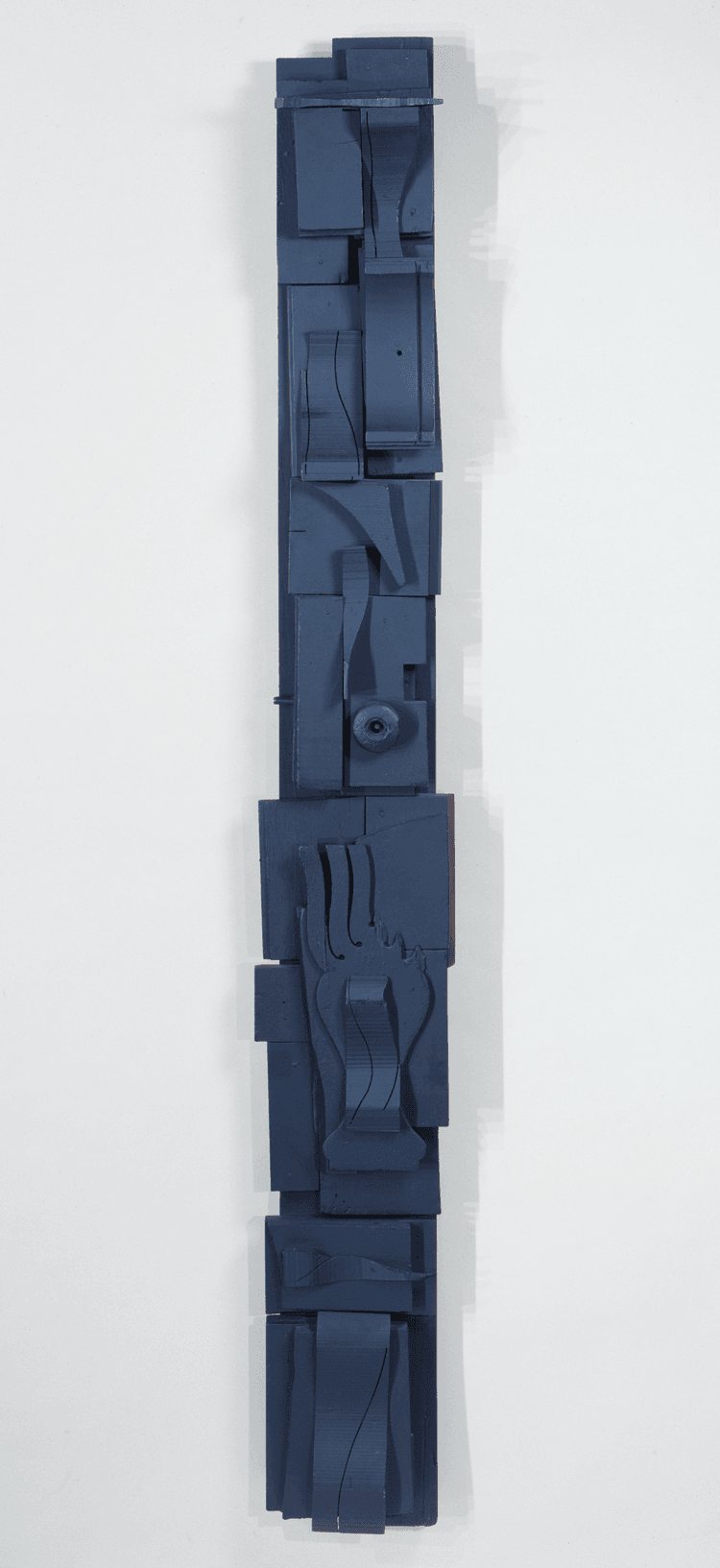

Louise Nevelson aimed at something that she called order, rightness, or spiritual essence. Early in her career, when materials and money were scarce, she roamed lower Manhattan looking for cast-off objects to use in her sculpture, and during a 1950 trip to Mexico, she became intrigued with the spiritual symbolism of pre-Columbian sculpture. Sky Totem is a flattened tower made from pieces of molding and scrap wood. The monochromatic black surface echoes the awe-inspiring totemic forms of ancient Mayan, African, and Northwest Coast cultures.

In 1985, Mrs. Roby and her foundation donated 175 paintings, drawings, and sculpture to the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Seventy paintings and sculpture from this collection were on view in the exhibition Modern Realism: The Sara Roby Foundation Collection at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Some of the most beloved works in the museum’s collection—such as Cape Cod Morning’ by Edward Hopper and Night in Bologna by Paul Cadmus—were part of this exhibition, which is a testament to the enduring relevance of the figurative tradition in American art. For information visit www.americanart.si.edu or call 202.633.1000.

Virginia Mecklenburg is chief curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.