A Brilliant Bit of Color: The Work of Walter Launt Palmer

.jpg) | |

Photograph of Walter Launt Palmer by Antonio Sorgato, Venice, Italy, 1885. Albumen silver print. Albany Institute of History & Art, Erastus Dow Palmer Papers (AQ 185). |

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932) has become known as the “painter of the American winter.” When one encounters his work today, it is usually a snow scene, which invariably displays his trademark blue shadows. Yet Palmer was a much more versatile artist, and his range of subjects — domestic interiors, European land and cityscapes, American woodlands, and snow-covered meadows — all reveal his ability to paint feeling and atmosphere into his physical settings.

Born in Albany, New York, to sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer and Mary Jane Seamans, Wallie, as he was known among family, grew up in a household where the arts flourished and artists such as Frederic Church, John Kensett, and Henry Kirke Brown were family friends. Church, in fact, tutored the young Palmer at his home, Olana, and later shared a studio with him in New York City at the Tenth Street Studio Building. Yet, despite his connections to the New York art community and his numerous travels to Europe, the Far East, Egypt, Greece, Mexico, Canada, and the American West, Palmer preferred living and working in his home community of Albany.

The Albany Institute of History & Art holds the largest public collection of Palmer’s works, as well as documentary archival materials given to the Institute by his daughter Beatrice. A Brilliant Bit of Color: The Work of Walter Launt Palmer, at the Institute through July 7, 2020, presents a broad overview of the artist’s life and work through paintings, watercolors, pastels, ceramics, and selections from the extensive Palmer manuscript collection. For information, call 518.463.4478 or visit www.albanyinstitute.org.

|

|

Faïence Cup. Decoration by Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), 1876. Glazed earthenware. Albany Institute of History & Art Purchase (2018.52). |

Palmer went to France for a second time in 1876, to continue his studies with the celebrated portrait painter and instructor Charles-Émile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, who first instructed the young American painter two years earlier while he was in Paris with his father, the sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer, and other family members. On May 14, 1876, Palmer wrote to his friend and fellow painter Lockwood DeForest that he was trying his hand at pottery at the “Fabrique de Faience.” This recently acquired faïence cup, painted with a realistic botanical design and signed and dated 1876, may be the only surviving example of Palmer’s foray into ceramics. The dark line drawing used to define the outline of the plant relates closely to three pen and ink botanical studies dated 1875 in the Albany Institute’s collection. Apart from these and an early still life of fern leaves in a ceramic jar, Palmer rarely focused such detailed attention on plants, favoring instead to paint or draw them as representative types in outdoor settings.

|

|

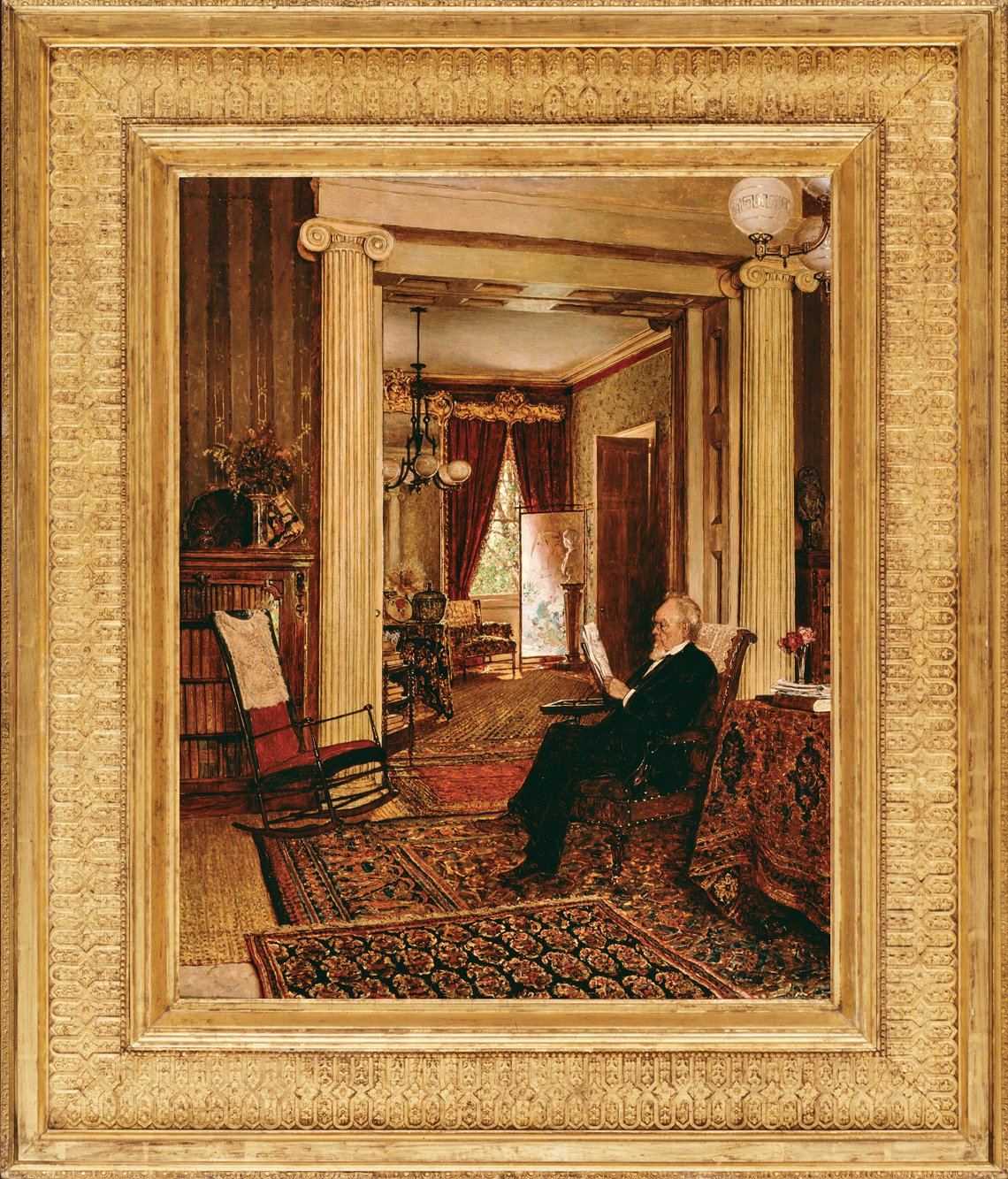

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Library at Arbour Hill, 1878. Oil on canvas, 25½ x 20¼ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of the heirs of the estate of Robert W. Olcott (1947.56.4). |

Although Palmer’s earliest paintings were winter landscapes, a subject he painted throughout his life, the first series to bring him recognition were his detailed views of domestic interiors. Palmer began painting house interiors in 1877, immediately after returning to the United States from his second period of study in Paris. This painting attracted favorable attention soon after its completion in 1878, both for Palmer’s meticulous attention to detail in the furnishings and for his perceptive and sensitive portrayal of the home’s owner, Albany banker Thomas Olcott, who sits reading in his library. Palmer received a commission for the painting from Olcott’s daughter, Mary Marvin Olcott, whose marble bust appears in the background near a painted Japanese screen in front of the parlor’s finely draped window. By including the bust, Palmer not only paid tribute to his patron but also incorporated a sculpted work by his father. The painting went on public view in June 1878 at Annesley and Vint Art Gallery in Albany.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Stanway Interior, 1881. Oil on canvas, 20½ x 18¼ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art Purchase (1967.9). |

Between 1877 and 1880, Palmer concentrated on painting interior views of American homes. Throughout these years he shared studio space at the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York with his teacher and friend, Hudson River School artist Frederic Church. Despite success with his American interiors and his close friendship with Church, Palmer made the decision in December 1880 to close up his studio and travel again to Europe. In Gloucestershire, England, Palmer found the opportunity to paint one of England’s great baronial halls, Stanway House, the Jacobean manor house belonging to Hugo Richard Charteris, 11th Earl of Wemyss and 7th Earl of March. Palmer’s view focuses on the magnificent oriel window in the great hall with a view of the church beyond. The building’s substantial proportions impart the feeling of airy spaciousness that his American interiors could not provide.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), The Garden Steps, 1886. Oil on canvas, 18 x 27 inches. Albany Institute of History & Art Purchase (1985.13). |

During his travels through Europe in 1881, Palmer visited Venice, a place that captivated and inspired him. Palmer’s interior paintings gradually declined during this decade due mostly to his constant complaint of eyestrain. In their place he turned to painting Venetian scenes and other landscapes. He also began to experiment with different mediums and with a looser handling of paint that was more impressionistic in style. The Garden Steps, however, follows a more academic approach, with tighter brushwork and its initial design being drawn in with brown tones, as Palmer recorded in his diary. He began laying in the “brown & tints” on February 27, and finished the painting a few weeks later on March 17.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Venetian Twilight, 1896. Watercolor, gouache, and crayon on composition board, 20 x 30 inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of Beatrice Palmer (1942.34.30). |

When Palmer exhibited his first major painting of Venice in Albany in 1882, it created a sensation. “It is a dreamy composition, naturally, and half closing one’s eyes it seems like a fairy delusion that might vanish with a breath,” wrote one reviewer for the Albany Express. Venetian Twilight, painted several years later, is every bit as dreamlike. “There is brilliant coloring in ‘A Venetian Twilight,’ in which the gold colored lights are pleasingly set off by the turquoise blue sky and water,” noted one reviewer when the painting went on view at the Avery Gallery in New York in December 1896. The work remained with Palmer and eventually passed to his daughter Beatrice, who donated it to the Albany Institute in 1942 along with several other paintings, sketches, photographs, and manuscript materials from her father.

|

|

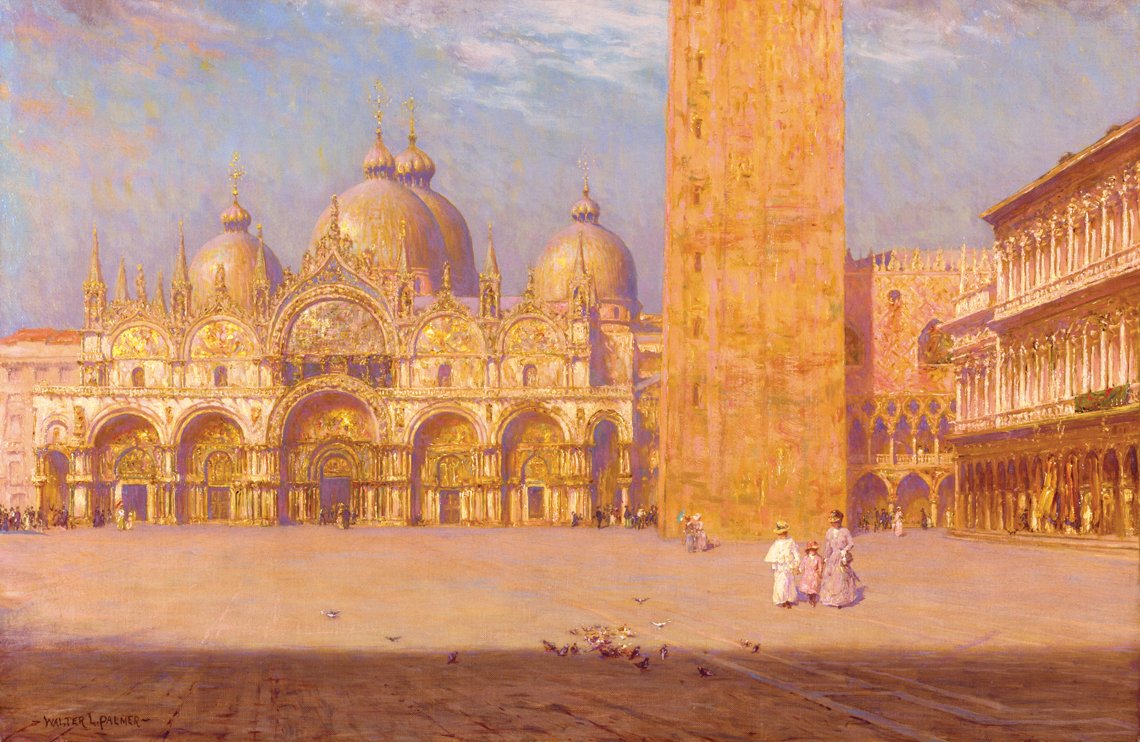

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), San Marco, 1895. Oil on composition board, 19 x 29 inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of Beatrice Palmer (1942.34.33). |

In 1895, Palmer produced two views of San Marco in Venice, a compact, vertical painting that displays the full height of the campanile, and the Albany Institute’s horizontal composition with a wider, more open view that imparts a grander sense of space. Here, Palmer included more of the Procuratie Nuove on the far right and he severely cropped the campanile, leaving it jutting off the top edge of the painting. His positioning of the campanile in this horizontal format divides the painting roughly into thirds, with two-thirds being given to San Marco on the left. For both paintings Palmer used the same color palette. When the vertical San Marco was shown in the National Academy exhibition in 1895, a reviewer in The New York Times remarked on its “brilliant bit of color.” Palmer’s use of blues and violets set against gold, green, and rose create a jewel-like impression. These same colors became something of a trademark for Palmer. He used them in other Venetian scenes and also in his popular winter landscapes, yet for each subject the colors create very different atmospheric effects.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), La Salute by Moonlight, 1895. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper mounted to composition board, 23⅞ x 17⅞ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of Elizabeth H. Odell (2001.12). |

This is one of Palmer’s most haunting Venetian paintings. It portrays the old domed Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute, situated on the Punta della Dogana near the end of the Grand Canal. The soft ripples of light reflected in the water and the evanescent plumes of pale violet mist illuminated by the veiled light of a full moon create a scene of near spiritual transcendence and serenity. When Palmer entered the work in the Boston Art Club’s 52nd Exhibition of Water Colors, it won Palmer the first prize of $250, and six years later, the watercolor was awarded the second-place silver medal at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Palmer painted other views of La Salute, and in 1902 the Albany Institute’s painting and three others depicting the venerable building at different times of day were shown together at Noé Galleries in New York. Art Amateur said of them: “The series of course calls to mind Monet’s famous series of Rouen Cathedral, but it is not every artist who can follow in Monet’s footsteps.”

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Wheatfield with Poppies, 1889–1890. Pastel on composition board, 22 x 31 inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of the estate of Catharine Gansevoort Lansing (1919.4.23). |

The wheat fields surrounding the town of Chantilly, north of Paris, had captured Palmer’s attention since his first journey to Europe during the years 1873 and 1874. Contained within a bound volume of sketches from that excursion, now at the Albany Institute, is a pen and ink drawing dated and inscribed “Chantilly/May 15, ‘74/near Paris,” which closely resembles the overall composition of this later pastel. Another pen and ink sketch of the same wheat field but with the addition of a lone female figure is pasted into a scrapbook the artist kept. That sketch became the model for an 1881 oil painting known as Wheatfield near Chantilly. The Albany Institute’s later pastel is a reworking of that landscape. The figure is gone; the cut and sheafed section of wheat has become smaller. But most noticeably, Palmer added bright red patches of corn poppies that enliven the landscape with color. At a distance the pastel landscape looks like a fine oil painting with quickly applied dabs and flicks of paint applied with a small or medium-sized brush. Only on closer inspection does it become evident that the landscape is built up from a rainbow palette of pastels, all applied with the deft hand of a painter.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Autumn Morning—Mist Clearing Away, 1892. Oil on canvas, 38¼ x 52¼ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of the estate of Dr. Leonard G. Stanley (1959.145). |

Early in 1892, Palmer debuted this, his largest canvas. It was an unusual subject for Palmer, but his move away from Venetian scenes and winter landscapes proved to be a good decision as the painting received critical approval in both Albany, where it went on view in February at Annesley’s Art Gallery, and in New York, at the National Academy exhibition. The landscape takes the viewer to the edge of the Delaware River, where low morning sunlight rakes across the terrain forming elongated shadows and shrouding the opposite hillside in a hazy violet mist. John G. Myers, owner of an Albany department store, lent the painting to the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, where it won a first prize out of the more than nine thousand pictures entered. The painting’s success must have brought some much needed joy into Palmer’s life, as he lost his wife, Georgianna, and newly born infant, Jessie, during childbirth in July 1892.

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), White World, 1932. Oil on canvas, 30¼ x 30⅛ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of Mrs. Ledyard (Dorothy Arnold Treat) Cogswell, Jr. (1955.14). |

Palmer’s snow scenes proliferated as the artist worked into the twentieth century. Eventually he painted little else. Palmer commented on his winter landscapes in an interview for the Boston Globe, in August 1923, while he was working at his summer studio in Gloucester, Massachusetts: “I don’t do anything else, really—haven’t for a long time. You know when you find the thing you can do best. It’s a good thing to stick to it.” White World was Palmer’s last painting, completed not long before his death in 1932. Like so many of his snow scenes, he painted a narrow slice of forest at dawn soon after a freshly fallen snow transformed the landscape into a magical world. Unlike his early winter landscapes, White World’s tangled mass of branches and saturated colors of blue and violet approach becoming an abstraction of a landscape; a view that may be rooted in reality, but one that sores to heights of imagination. In a 1910 article in Palette and Bench, Palmer advised artists to “paint from memory if you can, from nature if you must . . . Art is an interpretation, not an imitation, but unless equipped with a sound, thorough, scientific knowledge of his languages, an interpreter cannot hope to translate qualities the most subtle, the most intangible, the most precious.”

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Road to Olana, 1888. Water and gouache on paper, 13¼ x 17¼ inches. Albany Institute of History & Art; Gift of the estate of Miss Evelyn Newman (1964.31.40). |

Of all his prolific output—more than one thousand recorded works—Palmer’s snow scenes are his best known and admired, and Palmer himself has often been labeled the “painter of the American winter.” Most of his winter landscapes are uninhabited, but occasionally some reveal traces of human presence, as in this painting. Here, the deeply grooved tracks from sleighs lead the viewer up the carriage drive of the Hudson River home of Palmer’s friend and teacher, Frederic Church. Fir trees or hemlocks line the drive forming dense shadows illuminated occasionally with dappled sunlight. Palmer’s blue, violet, and green shadows attracted much attention during his lifetime.

W. Douglas McCombs is chief curator at the Albany Institute of History & Art, Albany, New York, and is the curator of A Brilliant Bit of Color.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.