“A Real Creator of Creators” How Mabel Dodge Luhan Catalyzed Southwest American Modernism

This archive article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

In February 1914, Marsden Hartley wrote to Alfred Stieglitz from Berlin: “Mabel Dodge is really the most remarkable woman I ever knew…a real creator of creators.” 1 In January, Mabel had written an introduction to Hartley’s exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery, 291, later published in the June 1914 issue of Stieglitz’s journal Camera Work. Hartley would be one of the first, and most important, of the numerous modernist artists and visionaries Mabel drew to Taos, New Mexico. While Indian artifacts in the Berlin Ethnographic Museum inspired Hartley’s first modernist works, in Taos, Hartley would engage with living Native American cultures. He would write a series of articles for national magazines touting Native Americans as the “first” and the only “original” American artists, and produced an extraordinary body of work that transformed his career (Fig. 1).

- Fig. 1: Marsden Hartley (1877–1943), Blessing the Melon: Indians Bring the Harvest to Christian Mary for Her Blessing, ca. 1918. Oil on canvas, 32-3/4 x 23-7/8 inches. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (1949-18-13). Hartley spent five months in Taos, at Mabel’s rented apartments in town, and seven months in Santa Fe, in 1918–1919.

American women patrons like Mabel Dodge Luhan (1879–1962) were as responsible for the careers of modernist artists like Hartley, and for shaping modernism, as were the critics, gallery owners, and museum entrepreneurs who have been given most of the credit. She was at the nexus of Southwestern modernism, which is marked by Anglo, Native American, and Hispano artists’ and patrons’ mutual influence on one another’s aesthetic ideals and cultural productions.2

Mabel Ganson grew up a “poor little rich girl” in one of the first families of Delaware Avenue, in Buffalo, New York, during the Gilded Age. Deprived of affection by her two unhappy parents, she tried to escape the stifling confines defined for wealthy Victorian women. Her first act of rebellion was turning her “Coming Out” party at Buffalo’s Twentieth-Century Club into a medieval pageant. Mabel took no interest in her first husband, Karl Evans, and she informed her second husband, Edwin Dodge, that she would marry him only if he provided her with a life of beauty. He did so by buying the magnificent Medicean Villa Curonia in Florence, Italy, in 1905. Here, Mabel Dodge created her first salon, hoping to revive the high point of European culture, the Italian Renaissance (Fig. 2).3

,-Buffalo-Mural.jpg)

- Fig. 5: Pop Chalee (Merina Lujan) (1906–1933), Buffalo Mural, n.d. Casein on canvas, 49 x 202 inches. Albuquerque International Airport, N.M. Merina Lujan was Tony Lujan’s niece. In the 1930s, Mabel encouraged her to attend the Dorothy Dunn School in Santa Fe, which produced many of the foremost Pueblo and Navajo easel painters.

- Fig. 6: Patricinio Barela (1900–1964), Death Cart/Muerte, 1931–1935. Wood. H. 37, W. 22, D. 41-1/2 in. The Harwood Museum of Art at the University of New Mexico, Taos, N.M.; Gift of WPA. Mabel was a patron of Barela’s and is believed to have encouraged him to carve larger pieces. During the 1930s, Barela was acclaimed in national exhibitions for his nontraditional and powerful expressionist woodcarvings.

By 1911, Mabel felt embalmed by the dead forms of Europe’s past. Meeting Gertrude and Leo Stein in Paris in April that year, she was introduced to their stunning modernist collection of Picassos, Matisses, Van Goghs, and Cézannes. The Steins stayed at the Villa Curonia twice the following year, during which time they converted Mabel to Modernism. Gertrude Stein’s synthetic-cubist word picture, Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia (1912), the only nonvisual work of art at the Armory Show of 1913, provided Stein with her first large-scale introduction to American audiences. During her last years in Florence, Mabel began to take on the roles of mentor and muse and became the most characterized “New Woman” of her time.4

With impeccable timing, Mabel returned to New York in November 1912. The number of radical ventures launched in the two years before the outbreak of World War I has never been matched in American history. In American Moderns, Christine Stansell suggests that the blank white walls of Mabel’s New York apartment at 23 Fifth Avenue, on the fashionable edge of Greenwich Village, “symbolized the blank canvas of modernism itself, its emptiness representing the world unpainted, unwritten, unthought, and entirely open to new interpretations. Her use of this space to house the period’s most famous salon in New York signified not only her readiness to host the new movement but also her desire and intention to shape and create it.” 5

Mabel took up the modernist credo with a vengeance, embracing free love, psychoanalysis, progressivism, anarchism, postimpressionist art, and political theater with equal enthusiasm, and placing herself as a student at the behest of the leaders of these movements. Alfred Stieglitz became her most important artistic “seer.” She befriended many of the artists in Alfred Stieglitz’s circle, including Georgia O’Keeffe, and was involved in the Armory Show, the most important exhibition of modern art to come to the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century, which opened February 7, 1913, at the 69th Street Regiment Armory building. She received one of the two honorary vice president titles given by the all-male board that planned the exhibition.

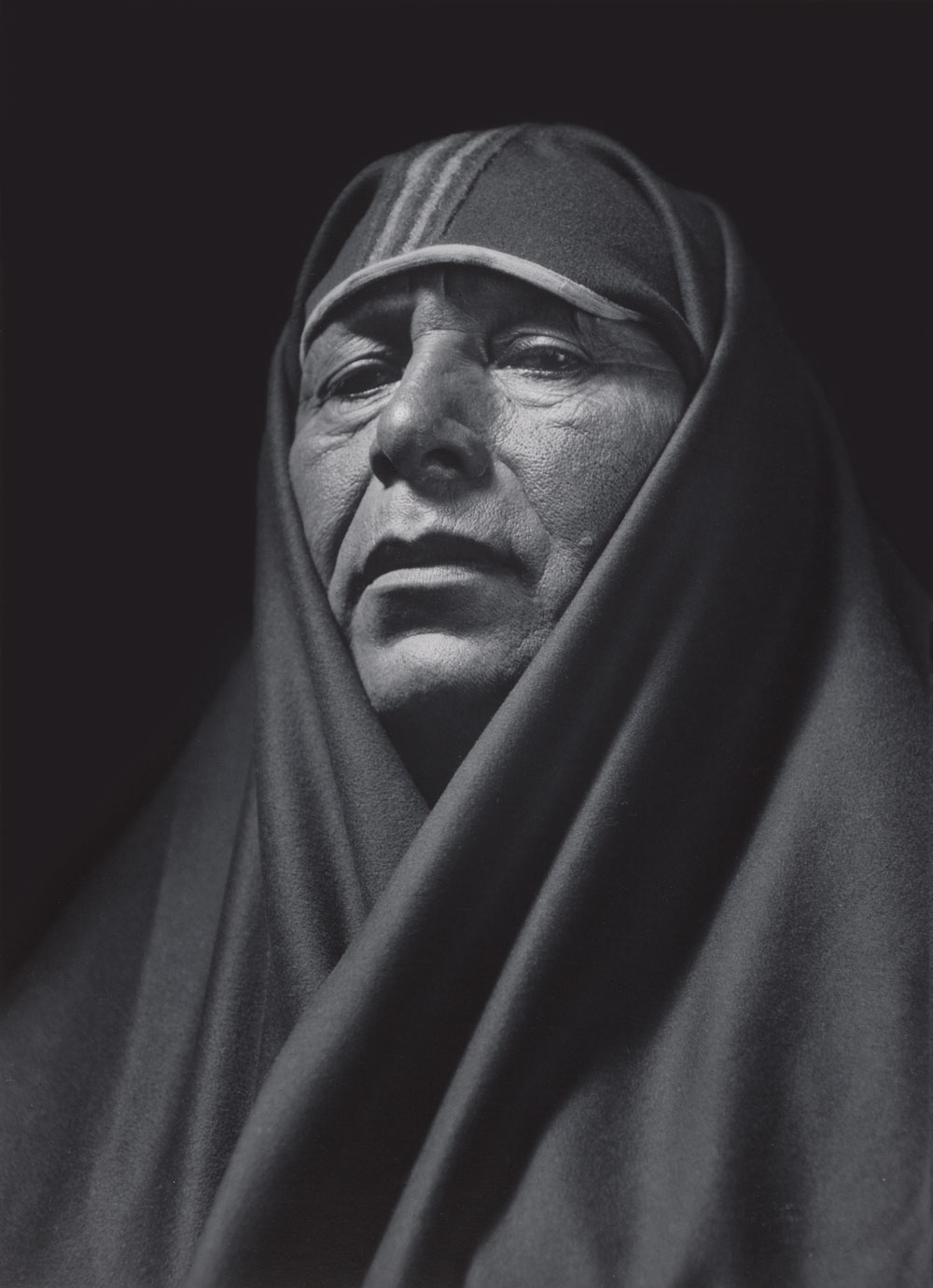

- Fig. 7: Ansel Adams (1902–1984), A Man from Taos, Tony Lujan, Taos Pueblo, 1930. Gelatin silver print, 175⁄16 x 13 inches. The Harwood Museum of Art of the University of New Mexico, Taos, N.M.; Gift of Mabel Dodge Luhan. ©Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. This photo was taken in Adams’ studio in San Francisco. It was part of his second professional portfolio, Taos Pueblo (1930), for which Mary Austin wrote the introduction. Austin was a noted literary figure, and a women’s and Indian rights activist, whom Mabel brought to Taos in 1919. She returned several times before settling in Santa Fe in 1924.

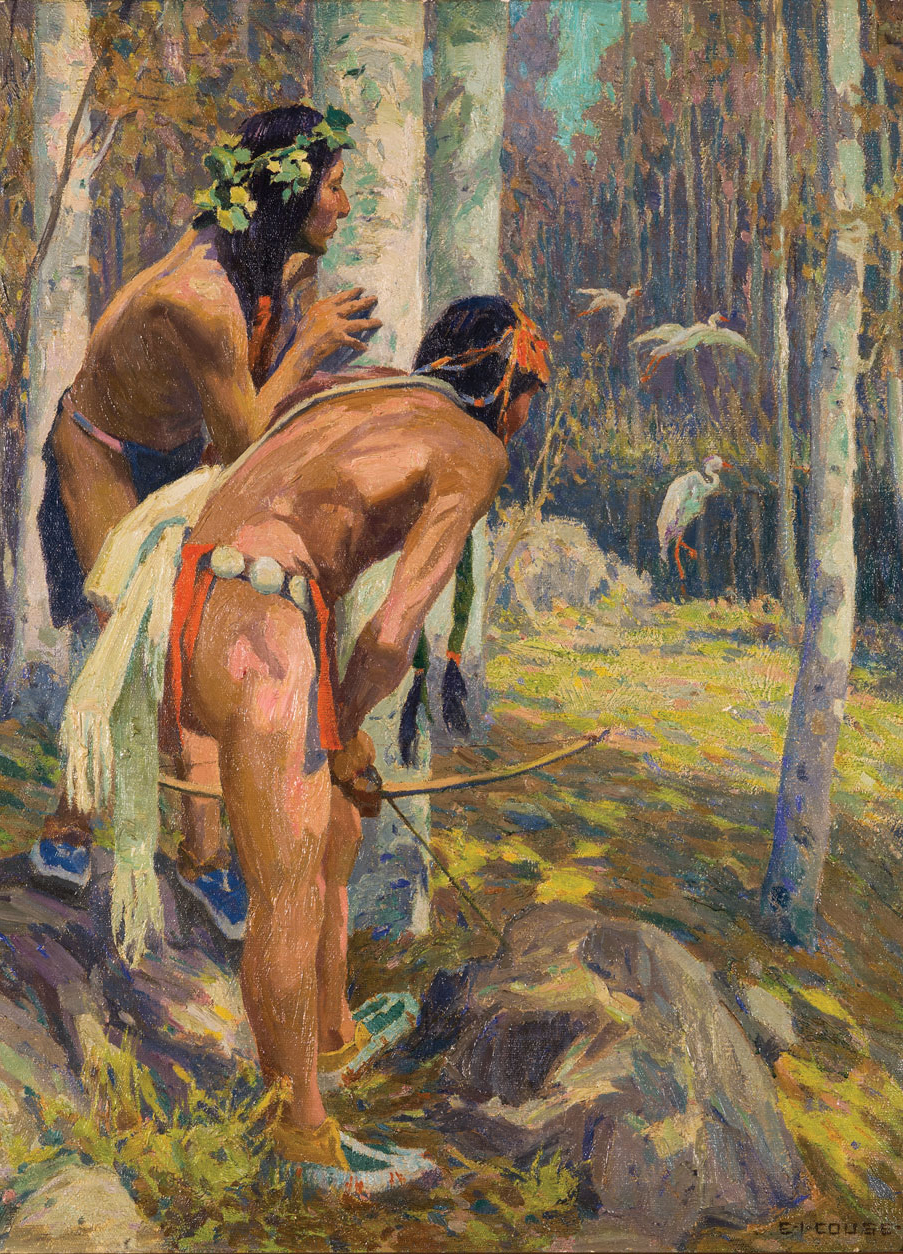

In January 1915, Mabel moved to Croton-on-Hudson in order to escape the hysteria of World War I, a “retreat” into nature that was prophetic of the move many American modernist artists would take to rural regions of the United States after the war. Mabel rented Finney Farm, where she brought some of her closest artist friends, including Marsden Hartley, and her new lover, postimpressionist painter Maurice Sterne. In April 1917, she married Sterne; a few months later, she sent him to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to gain new inspiration for his art. When asked later in life why she chose the remote outpost of Santa Fe, she said she had fallen in love with a painting of a Taos Indian by Irving Couse, whose work she likely saw during the November 1917 circuit exhibition of the Taos Society of Artists in New York City (Fig. 3).

From Santa Fe, Maurice wrote Mabel the letter that would alter her life and lead to Taos (population 3,000) and its environs becoming one of the centers of modern art, patronage, and Native American rights activism in the nation. “Dearest Girl,” he wrote her, on November 30, 1917, “Do you want an object in life? Save the Indians, their art-culture—reveal it to the world!” Over the next four decades, Mabel and her circle of artist friends put Taos on the map of modern American culture, creating a Paris West in the high desert. Without the circle Mabel had already established in New York, of course, this never would have happened (Fig. 4).

In Taos, Mabel took up Alfred Stieglitz’s call for the creation of a distinctive national culture rooted in an American “spirit of place.” She collected Pueblo easel paintings and Hispano religious art; organized some of the first exhibitions of these works in the country, and through her patronage and writing enabled them to enter the category of fine art (Figs. 5, 6). She drew some of Stieglitz’s most important acolytes to Taos in service to this vision: Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Paul and Rebecca Strand, and Georgia O’Keeffe. On January 1, 1918, she began building her seventeen-room Big House and five guesthouses, to which she drew some of the nation’s—and Europe’s—most “creative souls” over the next three decades. Sherry Smith sums up the role Mabel played: “She did not dabble in the region, she helped define it . . . She did not simply ‘play’ Indian, she married one.” 6 Tony Lujan became her fourth, and final, husband on April 18, 1923 (Fig. 7). (Mabel changed her last name to “Luhan” because her Anglo friends had difficulty pronouncing the Spanish jota.)

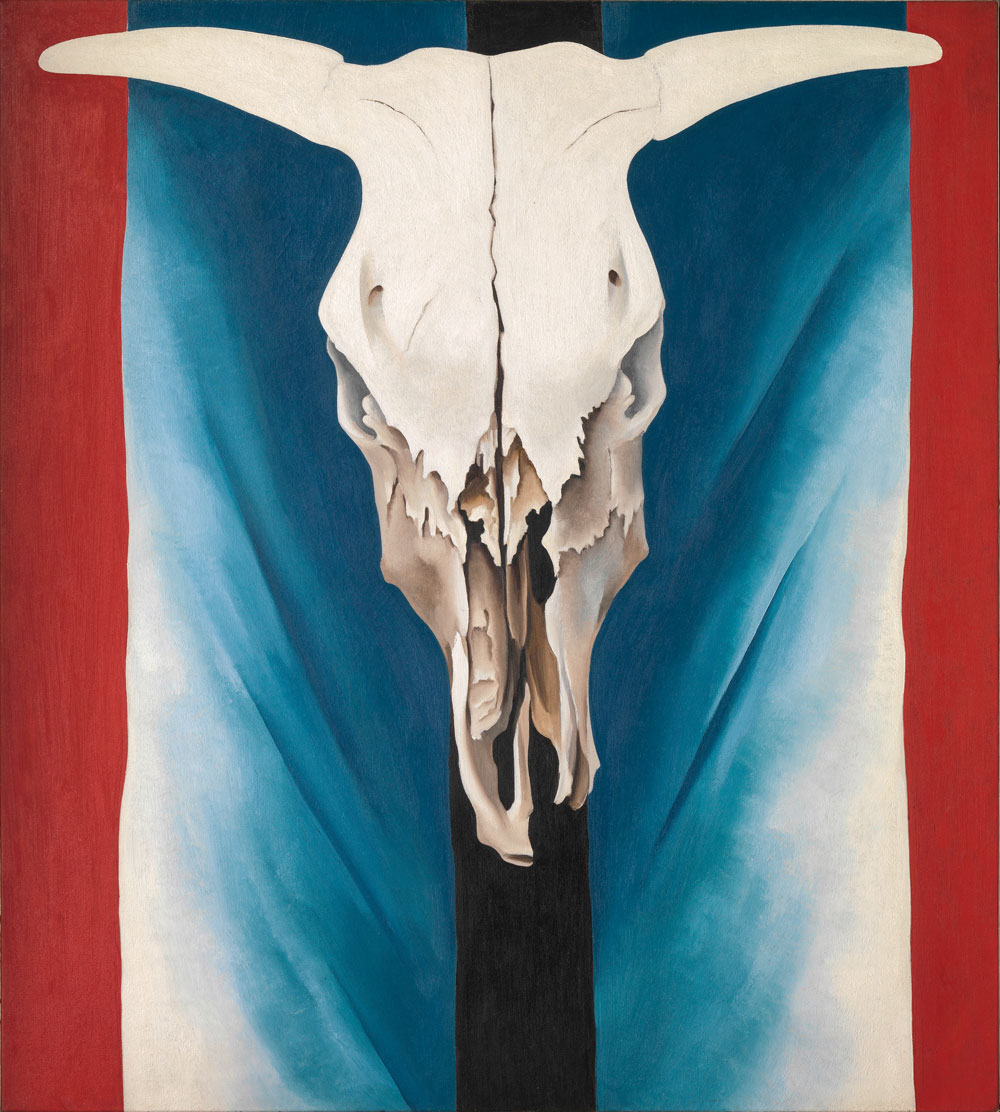

Many of the women artists Mabel drew to Taos—including Georgia O’Keeffe, Martha Graham, and Laura Gilpin—shared Mabel’s vision of the land as primal and liberating. That no one had mastered the spacious and thinly populated expanses of desert, mesa, and mountains of northern New Mexico was attractive to these women seeking to make their own imprint on American art and culture. O’Keeffe noted sardonically that while “the city men” back East were yearning to escape to Europe to write the Great American Novel, “I thought to myself, ‘I’ll make it an American painting’” (Fig. 8).7

- Fig. 8: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Cow Skull: Red, White, and Blue, 1931. Oil on canvas, 39-7/8 x 35-7/8 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1952 (52.203). O’Keeffe spent four months at the Lujan compound in the summer of 1929; six weeks, in the summer of 1930; and two weeks, in the summer of 1931.

Northern New Mexico was the place, Luhan argued, that would allow Anglo artists, writers, and reformers to reunite body and mind, spirit and matter, and in the process, discover the means by which their art and advocacy could do the same for American culture at large. Marsden Hartley hoped to replace the homogenized “melting pot” advocated by assimilationists with a national culture rooted in regional ethnic cultures. Maynard Dixon wrote “You can’t argue with those mountains—and if you live among them enough—like the Indian does—you don’t want to. They have something for us much more real than some imported style” (Fig. 9).8

Mabel established her estate, Los Gallos (The Roosters), with the utopian intention of altering human consciousness and human relationships through the built environment. For most who came, it served as a physical and spiritual oasis. Whether they established themselves permanently in northern New Mexico, or returned to the East or West coasts, the artists drawn by Luhan left Taos with their social ideals, their art, and themselves revitalized. And in so doing, they created a living legacy for Taos, which still remains a vibrant center for the arts.

- Fig. 9: Maynard Dixon (1875–1946), Watchers from the Housetop, 1931. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches. Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Ariz.; Museum purchase with funds provided by Western Art Associates (1971.15). Dixon and his photographer wife, Dorothea Lange, rented one of Mabel’s studios for nine months in 1931–1932.

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West, co-curated by Lois Rudnick and MaLin Wilson-Powell, is at the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, N.M., from May 22, 2016–September 11, 2016; at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, Albuquerque, N.M., from October 29, 2016–January 22, 2017; and at the Burchfield Penney Art Museum, in Buffalo, N.Y., from March 10, 2017–May 28, 2017. This essay is adapted from Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2016), available at www.mnmpress.org, or by calling 800.249.7737. For information on the exhibition, call 575.758.9826 or visit www.mabeldodgeluhan.org.

-----

Lois P. Rudnick is professor emerita of American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

All images are courtesy of Museum of New Mexico Press.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliatd with incollect.com.

2. For the broad range of Luhan’s mentoring, influence, and patronage in twentieth-century American art, see “A Real Creator of Creators’: How Mabel Dodge Luhan Catalyzed American Modernism,” in Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West, ed. Lois Rudnick and Malin Wilson-Powell (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2016).

3. For full biographical details, see Lois Rudnick, Mabel Dodge Luhan: New Woman, New Worlds (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984).

4. Ibid.

5. Christine Stansell, American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Making of a New Century (New York: Henry Holt, 2001), 106–107.

6. See Sherry Smith, Reimagining Indians: Native Americans through Anglo Eyes, 1880–1940 (New York: Oxford University Press), 187.

7. Georgia O’Keeffe, Georgia O’Keeffe: A Studio Book (New York: Viking Press, 1976), 58.

8. Marsden Hartley, Adventures in the Arts (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1921), 14; Maynard Dixon, Images of the Native American (San Francisco: Academy of Sciences, 1981), 36.