American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals

This archive article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Six miles off the coasts of southern New Hampshire and Maine, Appledore is the largest island in the Atlantic archipelago known as the Isles of Shoals. Childe Hassam (1859–1935), the foremost American impressionist of his generation, spent the three decades between 1886 and 1916 exploring Appledore. It was here that Hassam found a reliable and welcome retreat from urbanity as well as ongoing creative stimulation that inspired him to produce artistically new responses to beloved and familiar subject matter.

The exhibition American Impressionist: Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals, is the first in more than twenty-five years to examine Hassam’s sustained engagement with this storied site, and features forty-two of his finest interpretations of Appledore in oil and watercolor. The exhibition also represents a collective effort on the part of curators, geologists, and marine scientists to analyze and interpret Hassam’s responses to geography, geology, and meteorology, and his experiments with color, texture, and scale. Although the island’s cultural and surface topographies have changed dramatically over the last century, Appledore’s geology and the surrounding oceanic forces have remained relatively constant. These factors enabled the curators to corroborate Hassam’s painting sites and map them, leading to many new discoveries about Hassam’s paintings and his artistic practice.

So-called “diagnostic rocks”—easily identifiable markers that have not moved, eroded, or broken—can be identified in the paintings, as can intertidal zones of particular interest to marine scientists. The curators, working closely with the project’s marine biologist, determined how Hassam adjusted his position in relation to rocks and pools as he observed them, revealing how the artist often reframed, or manipulated the views, variety, and pattern of his rugged and watery surroundings. Collapsing and simultaneously highlighting distinctions between Appledore in Hassam’s day and Appledore now, enriches our appreciation of Hassam’s methods and deepens our understanding of his artistic range.

Text continues below images

With the 1848 opening of the grand hotel the Appledore House, vacationers began flocking to the island. Over time, the poet, prose writer, painter, gardener, and resident celebrity Celia Thaxter (1835–1894) further popularized the island, particularly with the publication of her celebrated book, Among the Isles of Shoals (1873). It was also Thaxter who first invited Hassam, the rising American art star, in 1886. During his first summers on Appledore, Hassam stuck close to the environs of the hotel and Thaxter’s cottage.

Hassam reveled in the view towards Babb’s Cove from the shaded piazza of Thaxter’s cottage. He routinely set up his easel there to paint the vista, which included the brilliant field of Iceland poppies cascading beyond the borders of her famous flower garden. As Thaxter wrote in 1894, “How beautiful they are, these grassy, rocky slopes shelving gradually to the sea, with here and there a mass of tall, blossoming grass softly swaying in the warm wind against the peaceful, pale blue water!”

Celia Thaxter’s garden was only fifty feet long by fifteen feet wide but contained at least fifty-seven varieties of flowers that thrived thanks to what she called her “advantageous method of grouping” and “love.” Hassam’s virtuosic garden watercolors inspired Thaxter to commission the artist to create “pictures and illuminations” for her landmark volume An Island Garden, published in 1894.

Hassam was drawn to the garden’s artful abundance, which he expressed in calligraphic brushwork and dynamic application of color. This work anticipates the exclamatory and poetical ways Thaxter described her garden in the 1894 volume: “What harmony of movement in all these radiant growths just stirred by the gentle air! . . . In the Iceland Poppy bed the ardent light has wooed a graceful company of drooping buds to blow, and their cups of delicate fire, orange and yellow, sway lightly on stems as slender as grass.”

In the wake of Thaxter’s death in 1894, Hassam took a five-year hiatus from Appledore. When he resumed annual trips in 1899 he began to study different areas of the island intensely and repeatedly. Except for 1910, when he was in Europe, Hassam faithfully visited Appledore each summer until 1916, usually unaccompanied. During this period, he pushed beyond the social and aesthetic zones of Thaxter’s cottage, her celebrated garden, and the commodious hotel complex. He was intensely prolific in 1907, the year he produced this painting of Sylph’s Rock, a large outcrop on Appledore’s northeast ledges of granitic gneiss rock transected by a trap dike. Hassam painted the rock’s south face from different viewpoints on at least three different occasions. To make the rock have the monumental appearance it possesses in this painting but not exactly in reality, he eliminated the foreground and substantially manipulated the angles so they would converge and appear as a single mass with great scale.

After 1899, Hassam gravitated to the geology of Appledore’s coves and the beauty of the encircling sea. In this painting, Hassam plunges the viewer into the scene by eliminating the foreground. Sylph’s Rock at the left edge of the painting sets up a diagonal leading from the craggy cliffs, down across the low ledges, the breaking waves, and the water out to Duck Island on the horizon.

In Among the Isles of Shoals, Thaxter described the low ledges such as those seen in Hassam’s painting as “swept by every wind that blows . . . barren, bleak and bare . . . mere heaps of tumbling granite in the wide and lonely sea.” Yet, the shoals proved not as inhospitable as first impressions might suggest. Visitors basked on those large rocks warmed by the sun, taking in the expansive views. For Hassam, the allure was to paint these elements of ocean and sky and find the colors in the “bleached rocks” Thaxter described—while eliminating the throngs of tourists from his compositions.

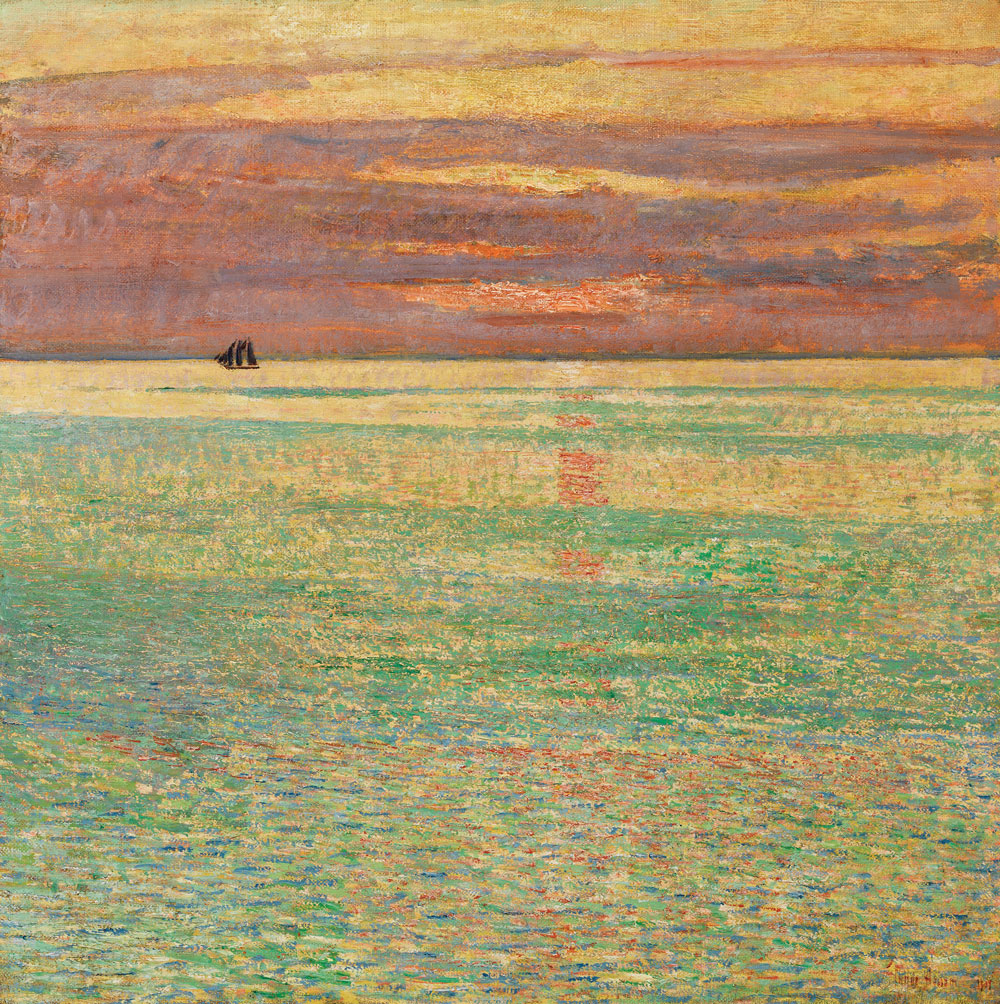

West Wind, Isles of Shoals instantly conveys the sort of blissful summer atmosphere that lured vacationers, celebrated artists and musicians, and the literati to Appledore, where they could be lulled by what Thaxter called the “framework of the sea.” During a memorable two-week stay on Appledore in September 1852, Thaxter’s friend Nathaniel Hawthorne recorded in his journal: “Here is another beautiful morning, with the sun dimpling in the early sunshine. Four sail-boats are in sight, motionless on the sea, with the whiteness of their sails reflected in it . . . The crickets sing, and I hear the chirping of birds besides.”

In an 1892 interview, Hassam stated, “The word ‘impression’ as applied to art has been abused, and the general acceptance of the term has become perverted. It really means the only truth, because it means going straight to nature for inspiration, and not allowing tradition to dictate to your brush . . . the true impressionism is realism.” Sunset at Sea is emblematic of the ways in which Hassam used fidelity to what he observed at Appledore to push his impressionistic technique and artistic practice. Hassam painted sunsets on many occasions, often on the lids of cigar boxes to quickly capture at small scale the fleeting fireworks of color for friends and patrons. But for this canvas, he chose a large, square format in which to compose horizontal bands and dashes of color into an aesthetic meditation on twilight.

Despite its title, this canvas actually pictures the north gorge—a trap dike that dramatically intersects another trap dike. The erosion of soft basalt rock “trapped” between walls of hard granite over millennia forms these narrow gorges called trap dikes that are cavernous at low tide. At high tide, the ocean water rushes from both sides into the central intersection. Nineteenth-century guidebooks called this geological marvel “Neptune’s Hall;” today, tongue-in-cheek, it’s nicknamed “Broadway and 42nd.”

Hassam’s frequent takes on “Broadway and 42nd” evolved over three decades, from illustrative in the 1880s, to far more experimental by 1912, the year he made this painting. Here Hassam looked directly into the gorge and set the scene against a high horizon line, hinting at the disorienting and powerful impact of the incessant tidal flows. In this work, the artist’s color choices and brushwork emphasized the constant movement of water and shifting effects of light and color on rocks and sea.

One of Hassam’s most prolific seasons on Appledore was the summer of 1912, when he sought out new and more challenging views around the island’s perimeter. Concentrating on watercolor, he embraced the medium’s characteristics and portability. The inlet at the mouth of Siren’s Cove and Devil’s Dance Floor on the northeastern edge of the island proved especially compelling to Hassam as a new subject.

What Hassam called this “beryl” green or “dark” pool of water inspired him to climb down the ledges to look closely at the inlet’s watery depths, and The Cove is one of four watercolors he made of this site. Hassam used the medium’s fluidity and transparency to express the varying effects and colors of reflections on the water in relation to the pool’s translucence. And for each nearly abstract painting, he slightly adjusted his vantage point at different tidal and light levels, then, reframed his composition to look anew at the range of tints and textures in the pool’s aqueous emeralds and sapphires and in the surrounding rocks’ coarse russets.

Text continued from above

Evident in Hassam’s colorful paintings of Appledore are the very intricacies of geological and marine form, texture, and light that today are areas of study for scientists at the Shoals Marine Laboratory, which has been Appledore’s main occupant for fifty years, as well as for contemporary photographer Alexandra de Steiguer. De Steiguer is winter caretaker of the Star Island Family Conference and Retreat Center on neighboring Star Island. The North Carolina Museum of Art and the Peabody Essex Museum commissioned de Steiguer to create a suite of black-and-white photographs for the exhibition’s accompanying publication, a selection from which will be on view. De Steiguer’s and the scientists’ profound familiarity with the Isles of Shoals resonates deeply with Hassam’s strong connection to the place and the importance of such ties over time to the creative process.

American Impressionist Childe Hassam and the Isles of Shoals is organized by the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina (on view through June 19) and the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts (on view July 16–November 6), in cooperation with the Shoals Marine Laboratory. For more information, visit www.pem.org or call 866.745.1876. An illustrated catalogue edited by Austen Barron Bailly and John W. Coffey, with contributions by Austen Barron Bailly, Kathleen M. Burnside, John W. Coffey, and Hal Weeks, and a photo essay by Alexandra de Steiguer, distributed by Yale University Press, accompanies the exhibition (www.pemshop.com).

-----

Austen Barron Bailly is the George Putnam Curator of American Art, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.