American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds

|

From their ancient origins in China and Greece to their nineteenth-century American peak, weathervanes have populated urban and rural landscapes around the world for millennia. Beginning in the 700s, churches throughout Europe topped their steeples with “weathercocks” symbolic of Christian faith. In the middle ages, vanes took their name and form from heraldic flags, or fanes, flown from castle towers as proud displays of coats of arms. Although fundamentally tools to show the direction of the wind, weathervanes have always been aesthetic objects designed to capture attention and signal pride and status. As omnipresent ornaments in Western architecture from the eighth to the early twentieth centuries, vanes also served as way-finders, offering cues to the activities taking place within the buildings they topped, while orienting inhabitants to the function of the architecture around them.

Over time, weathervanes have taken on complex layers of purpose and cultural meaning. In the United States, their forms have become significant markers of American identity. Weathervanes were often employed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to express political pride as well as social status. In the early twentieth century, these objects were “rediscovered” by folk art collectors, who saw them as icons of a uniquely American sense of artistry and ingenuity or revered them as symbols of a bygone era.

Brought down from their high perches and into the human realm, these objects reveal their full histories—as tools, symbols, and works of art. In their wide-ranging forms, expressive character, and weathered surfaces, vanes spark the imagination while communicating multiple aspects of their history. Considered as a group, weathervanes can be read as cultural texts, documenting some of the aspirations, achievements, and anxieties of American consumers.

|

|

Fig. 1: Marian Page, Weather Vane: Rooster, ca. 1939. Watercolor and graphite on paper rendering of actual vane. 1313⁄16 x 13¾ inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Index of American Design (1943.8.16458). Crafted by Shem Drowne (1683–1774) of Boston, Massachusetts, America’s first documented weathervane maker, this was the first rooster weathervane, or “weathercock,” known to have been made by an American rather than imported from Europe. Crafted for the New Brick Church on Hanover Street in Boston’s North End (where Drowne’s shop was located), the vane is more than five feet tall and wide. Dubbed “The Revenge Church” because it was built by dissenters of an existing church to protest a new minister, it is said that members chose a rooster to call attention to the Reverend Peter Thatcher’s first name and the biblical story of Peter’s betrayal of Jesus. Legend has it that “when the cock was placed upon the spindle, a merry fellow straddled over it and crowed three times to complete the ceremony.” In 1873, the vane was moved across the Charles River to top the First Church Congregational in Cambridge, where it can be seen today. Drowne’s best-known surviving vane is the grasshopper that still tops Faneuil Hall in Boston. |

|

Fig. 2: Ezra Ames and Bela Dexter, Heart and Hand, Chelsea, Massachusetts, 1839. Carved white pine with original paint, 21 x 39 in. Private collection. Photograph courtesy David A. Schorsch and Eileen M. Smiles. This unique weathervane is documented in a letter from the makers, found folded up inside of the hollow center of the heart section, along with several Boston newspapers from June 1839. The letter states that “This heart and hand was made by Ezra Ames and painted by Bela Dexter [and] it is destined to be a weathervane for Read Taft of Roxbury.” Taft was the proprietor of a Roxbury hotel where this vane may have served as a welcoming sign. |

|

Emblems of Identity & Historical Memory

While the earliest weathervanes used in America were imported from abroad, a local craftsmanship tradition soon sprang up. Boston was home to the first documented American weathervane maker, Shem Drowne (1683–1774), whose work included such iconic forms as the rooster seen here (Fig. 1). From early on, American weathervanes have carried associations with historical memory, at times even taking on mystical implications. In the words of nineteenth-century novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of Drowne’s vanes became an animate presence—a witness to events taking place on the streets below, like a “sentinel watch[ing] over the city.” Such imagery captures the sense of wonder historically evoked by these objects, which was often linked to an impulse to personify weathervanes. Examples such as a Heart in Hand (Fig. 2) and trumpeting Angel Gabriel (Fig. 3) have served as time capsules, carrying notes within them from makers or later stewards of these life-like objects—further suggesting the role they have played as keepers of history and memory, and presaging their treatment by early twentieth-century folk art collectors as symbols of a distinctive American artistic heritage.

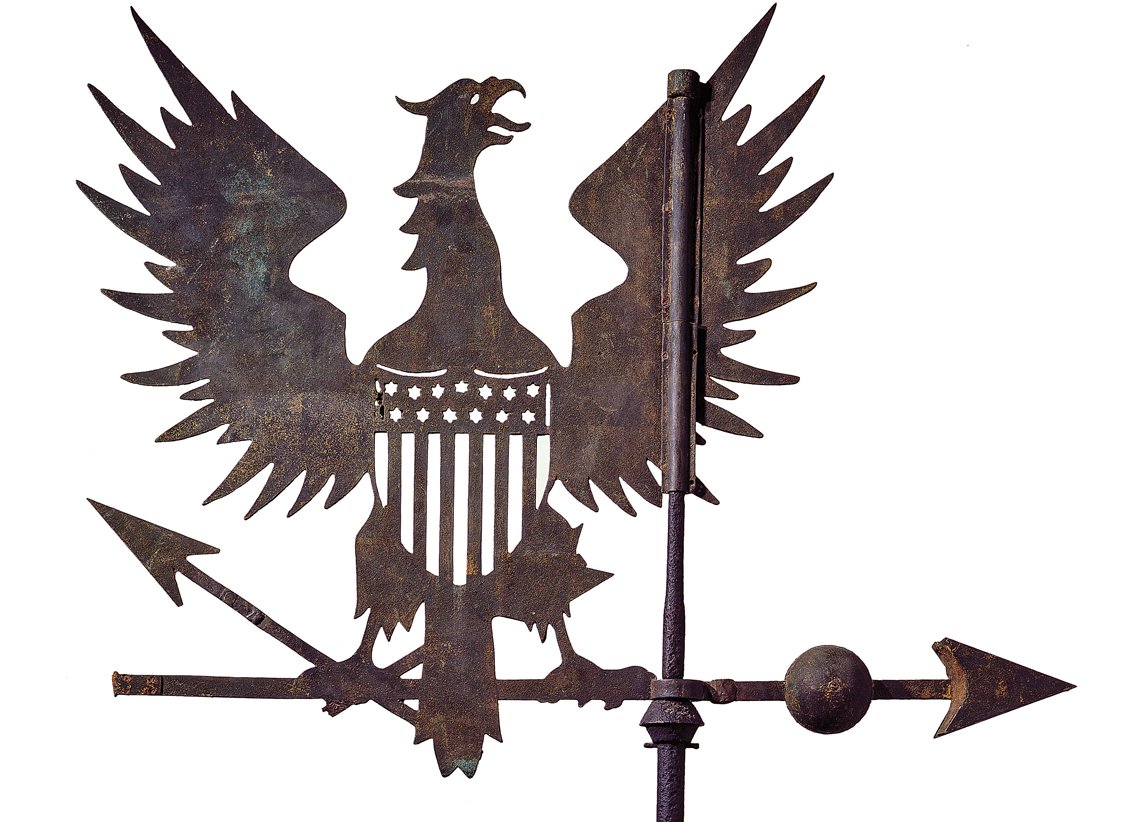

The original purchasers of American weathervanes chose themes that held symbolic meaning for them. Taking the form of eagles and other patriotic emblems, such vanes served as badges of political identity from the era of the young Republic well into the nineteenth century. A bold Eagle and Shield vane (Fig. 4) represents the exuberant patriotism of the early United States, while the Dove of Peace (Fig. 5) speaks to George Washington’s optimism for the new nation. Goddess of Liberty-form vanes (see Fig. 8) were made around the time of the Civil War but reflect the iconography of the Revolutionary era, capturing a continuity of national sentiment across generations.

|

|

Fig. 3: Gould and Hazlett, Archangel Gabriel, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1840. Gold leaf on iron and copper, 28½ x 71½ x 6 in. Collection of Kendra and Allan Daniel. Photograph by George Kamper. Beginning in the Middle Ages, Christian churches in Europe were often topped with symbolic weathervanes. The practice was brought to America by early settlers from the British Isles and the Netherlands. The use of the figure of Gabriel, the only angel named in the Bible, became popular in America during the great religious revival of the 1830s and 1840s. The body of this weathervane is sheet copper while the horn is three-dimensional. The vane was made for the Universalist Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and later moved to another church in the town. When taken down, a note inside the horn identified the makers. A nearly identical example attributed to the same makers topped a Belfast, Maine, church and is now in a private collection. |

|

Fig. 4: Eagle and Shield, Artist unidentified, possibly Boston or Canton, Massachusetts, ca. 1800. Cast bell metal, 36 x 43½ x 4 in. American Folk Art Museum; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Francis S. Andrews (1982.6.4). Photograph by John Parnell This patriotic Federal-era vane is made of bell metal, a type of bronze with a high copper-to-tin ratio, which has been used to cast bells since ancient times. The possible creator of this vane is Paul Revere (1735–1818), a silversmith, engraver, businessman, and bell maker. Revere cast hundreds of bells at his foundry in Boston between 1787 and when he and his son Joseph moved the foundry to Canton in 1804; this cast bell-metal vane may have been made at one of them. The vane’s design was likely inspired by the Great Seal of the United States, approved by Congress in 1782. |

|

Fig. 5: Dove of Peace, Joseph Rakestraw, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1787. Copper, iron, lead, gilt, and paint, 34¾ x 42½ in. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, transferred to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association through the generosity of John Augustine Washington III, 1860 (w-2492). George Washington commissioned this vane for the cupola of his mansion and chose its subject to symbolize his hopes for the new nation he would soon be leading as its first president. He provided specific instructions to the maker, writing to the architect Joseph Rakestraw that he “should like to have a bird . . . with an olive branch in its Mouth. The bird need not be large (for I do not expect that it will traverse with the wind and therefore may receive the real shape of a bird, with spread wings).” The vane is depicted above the cupola in Edward Savage’s circa 1787–1792 painting The West Front of Mount Vernon. Rakestraw fabricated the vane in Philadelphia in the late summer of 1787, while Washington was presiding over the Constitutional Convention. This original vane was replaced with an exact replica in 1993 and is now exhibited in the Donald W. Reynolds Museum at Mount Vernon. It was regilded and painted after it came inside for the last time. |

|

The Business of Weathervanes

Weathervane-making gained significant speed in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, when numerous manufacturers developed businesses, especially in Massachusetts and, later, in New York. During this period of broad industrial growth in the United States, models of business efficiency advanced quickly, and weathervane-makers developed new ways to keep up with the competition. Advertising broadsides and illustrated trade cards allowed vane-makers to showcase their wares, laying out the range of available options. Buyers could select vanes that met their needs based on price, size, and theme. Well-known makers such as J. Howard (Fig. 6), A. L. Jewell (Fig. 7), and Cushing & White (Fig. 8) vied with one another to provide original ideas while also offering popular forms such as roosters, horses, and other domestic and wild animals.

In the late nineteenth century, the high demand for weathervanes and the development of efficient manufacturing techniques brought about creative flights of fancy, spawning witches (Fig. 9), dragons, and other mythological figures. In an indication of the preoccupations of a rapidly industrializing society, weathervanes also took up motifs of innovation, exemplified by forms such as locomotives, cars, and planes (Figs. 10, 11). Throughout the course of the nineteenth century, weathervanes continued to take on various expressions of pride and identity. Forms such as eagles and representations of “Liberty” celebrated national sentiment, with the Statue of Liberty (Fig. 12) joining the earlier personification of the goddess recognizable from her staff and cap.

|

|

Fig. 6: Large Deer, J. Howard & Co., West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, ca. 1856–67. Molded copper and cast zinc, gilded 35 x 25 x 6 in. Collection of Kendra and Allan Daniel Photograph by John Currens. From at least 1850 to 1867, Jonathan Howard (1806–1889), his younger brother Charles Howard III (1817–1907), and Jonathan’s son John Williams Howard (1836–1865) apparently worked in various combinations in the manufacture of weathervanes in West Bridgewater, about twenty-fives miles south of Boston. By 1856, Charles returned to farming and the company changed from J. & C. Howard & Co., to J. Howard & Co., responsible for this large deer vane. Although it is not known who designed them or carved their patterns, the Howards’ products have long been considered the most elegant and refined of all manufactured weathervanes. This “Large Deer” vane is included in J. Howard’s price list of circa 1856, along with a small “swelled” deer. Large examples like this one wholesaled for seventeen dollars each. The vane was regilded long ago and its overall gold finish is close to the way it would have looked when it came out of the Howard shop. |

|

Fig. 7: Eagle, A. L. Jewell & Co., Waltham, Massachusetts, ca. 1860. Molded copper and cast zinc, 31 x 42 x 19 in. Collection of Barbara and John Wilkerson Photograph by Don Roman. In 1852, Alvin Leonard Jewell (1821-1867) founded the firm of A. L. Jewell, a metal-working business in Waltham listing weathervanes among the wares. Jewell and the Howards were among the first generation of commercial weathervane manufacturers in Massachusetts. Jewell’s innovative designs were copied by later manufacturers, though the occasional use of a die-stamp of his name and the copious line-cuts in print ads, illustrated price lists, broadsides, and trade cards he published help distinguish examples from his shop; he was also the first manufacturer to have his vanes photographed. Jewell continually added new designs to his line, which ultimately encompassed eighty different models. Jewell featured the powerful eagle form, shown here, which he made in two sizes, on his billhead and stationery as well as in his advertisements and broadsides. A distinguishing feature of Jewell’s vanes is the wide-open eyes on his cast heads, which are inscribed ovals that surround large convex pupils. |

|

Fig. 8: Goddess of Liberty, Cushing & White, Waltham, Massachusetts, ca. 1868–70. Molded copper and cast zinc with traces of old paint and gilt, 40¾ x 29¼ x 5¾ in. Collection of Michael and Patricia Del Castello. Photograph courtesy of Olde Hope Antiques, Inc. The firm of Cushing & White were among the successors to the first generation of weathervane manufacturers in Massachusetts. It was Leonard W. Cushing of Waltham who purchased the inventory, molds, and tools from the estate of A. L. Jewell in 1867; his partner was Stillman White and together they formed Cushing & White. This weathervane is A. L. Jewell’s design, which he patented on September 12, 1865 and which Cushing & White continued to use to produce this iconic form. A metal label attached to the vane’s lower left side has the patent date encircled by the names “Cushing & White.” |

|

Fig. 9: Witch Riding Crescent Moon (detail), W. H. Mullins, Salem, Ohio, ca. 1891. Copper, wrought iron, and wire. H. 99 in. Collection of Donna and Marvin Schwartz Photograph by Adam Reich. This is the only known authentic example of this large and complex weathervane design. The witch’s face and hands are iron, and her broom is made of tightly packed strands of wire. W. H. Mullins illustrated this form without directionals in his 1891 catalog and offered the elaborate finial for $160. In 1882, Mullins became one of the largest sheet metal companies in the United States, creating everything from weathervanes and outdoor statuary to entire building fronts; he later expanded into boats, launches, and automobile parts and bodies. He developed an innovative method of die-stamping copper, which was much more efficient than the hand hammering practiced by other manufacturers. |

|

Fig. 10: Touring Car and Driver, W. A. Snow Iron Works, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1910. Molded copper with traces of gilt. H. from bottom of wheels 18 in. Collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren. Photograph by Adam Reich. This remarkably detailed piece was mounted on the top of the Manor Crescent Building on Bedford Street in Lexington, Massachusetts, which served as a gas station and grocery store. Automobiles were still very much a novelty in 1910. This vane’s presence atop a gas station would have represented a striking addition to the local landscape. The complexity of the vane’s design and workmanship would have been invisible to the naked eye, however, in its perch above the building. W. A. Snow Iron Works manufactured stable fixtures, cow barn fittings, wrought-iron fences, outdoor seating, and more, including weathervanes. The 1894 catalog only devotes twenty of its 148 pages to vanes. Even so, the company continued to innovate. In addition to the standard racehorses, cows, roosters, banners, and scrolls, a company broadside published around 1910 includes an early touring car and driver, seen here, and a sulky with pneumatic tires. |

|

Fig. 11: The Blériot XI Monoplane, Artist unidentified, from the Poland Spring House, Poland Spring, Maine, ca. 1909–14. Copper, 10 x 57¼ x 55 in. Collection of Michael and Patricia Del Castello. Photograph by Michael Lynberg. Louis Blériot was a pioneering French aviator and engineer. This singular American weathervane is a carefully observed representation of the small, fragile monoplane that Blériot flew on July 25, 1909 for the first-ever airplane crossing of the English Channel. The fete electrified the world and made the pilot an international celebrity. The vane was probably made on commission for the Poland Spring House hotel in Poland Spring, Maine, where it was placed not long after Blériot’s epic flight. This vane is a unique sculpture, unparalleled in its scale and level of detail. Nothing else remotely like it is known. |

|

Fig. 12: Liberty Enlightening the World , J. L. Mott Iron Works, New York and Chicago, ca. 1885–92. Molded copper, gilded. H. 53 in. Collection of Donna and Marvin Schwartz. Photograph Courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc. © 2020. Libertas, the Roman goddess of freedom, was adopted by American revolutionaries such as Paul Revere and Thomas Paine; it became one of the United States’ most enduring symbols, depicted on currency and stamps as well as in paintings and sculptures. New York harbors’ Statue of Liberty would inspire many further iterations of Liberty’s personification in American visual culture, following its delivery from France in 1885 and its dedication in 1886. The J. L. Mott Iron Works was founded in 1828 by Jordan Lawrence Mott (1799–1866). His small iron works, located in the South Bronx, grew into a major industrial center and built him a fortune. His son, J. L. Mott, Jr. (1829–1915), expanded the business to include, among other things, “vanes, bannerets, and finials.” In an 1892 catalogue, in addition to usual and unusual horses, he also produced a number of gods and goddesses as well as contemporary figures such as baseball batters and female tennis players. |

|

Fig. 13: Curlew, Artist unidentified, Seaville, New Jersey, ca. 1874. Gold leaf on sheet metal with iron straps, 46⅛ x 92¼ x ⅜ in. American Folk Art Museum; Gift of Alice Kaplan, trustee (1977–1989) (2001.3.2). Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor. This unique and vastly oversized representation of a local shorebird species was made for the Curlew Bay Club in Seaville, New Jersey. The vane topped a two-story barn behind the clubhouse through the 1940s. Clubhouses and other sporting venues were often sites for thematic weathervanes that signaled the building’s purpose. |

|

Weathervanes as American Folk Art

Although demand for new weathervanes waned in the early twentieth century, around this same time, dealers and collectors began to recognize the appeal of these objects as artworks and to display them in art exhibitions. This interest formed part of a new movement to appreciate American “folk art”—works created outside the context of an academic art establishment. Collectors during this time championed American weathervanes as overlooked but significant forerunners in a national sculptural tradition—and also as symbols of an older, seemingly simpler time.

The passion for weathervanes as art objects would continue to grow throughout the century, reaching a plateau just before the 1976 bicentennial with the seminal show The Flowering of American Folk Art. That exhibition included the Curlew vane (Fig. 13) seen here, along with other icons of the folk art collecting tradition. Strikingly modern in its bold silhouette, this form exemplifies the allure of graphic simplicity for collectors of early American folk art.

American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds, on view at the American Folk Art Museum from June 23, 2021–January 2, 2022, is the first exhibition in decades to treat this topic comprehensively. Accompanied by a 256-page book by Robert Shaw, the show explores these objects’ rich layers of meaning through a display of remarkable American weathervanes crafted between the 1760s and 1914.

Robert Shaw is an independent curator and Emelie Gevalt is curator of Folk Art at the American Folk Art Museum, NYC

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|