D. Wigmore Fine Art Explores the Influence of Precisionism

Precisionist artworks are characterized by their sharp focus, unexpected viewpoints, and dynamic compositions -- attributes that could also be used to describe the current exhibition at D. Wigmore Fine Art in New York. A smart and deftly edited show, Adapting Precisionism: 1925-1946 not only explores the role of architecture in Precisionist paintings, but Precisionism’s profound influence on the evolution of modern art.

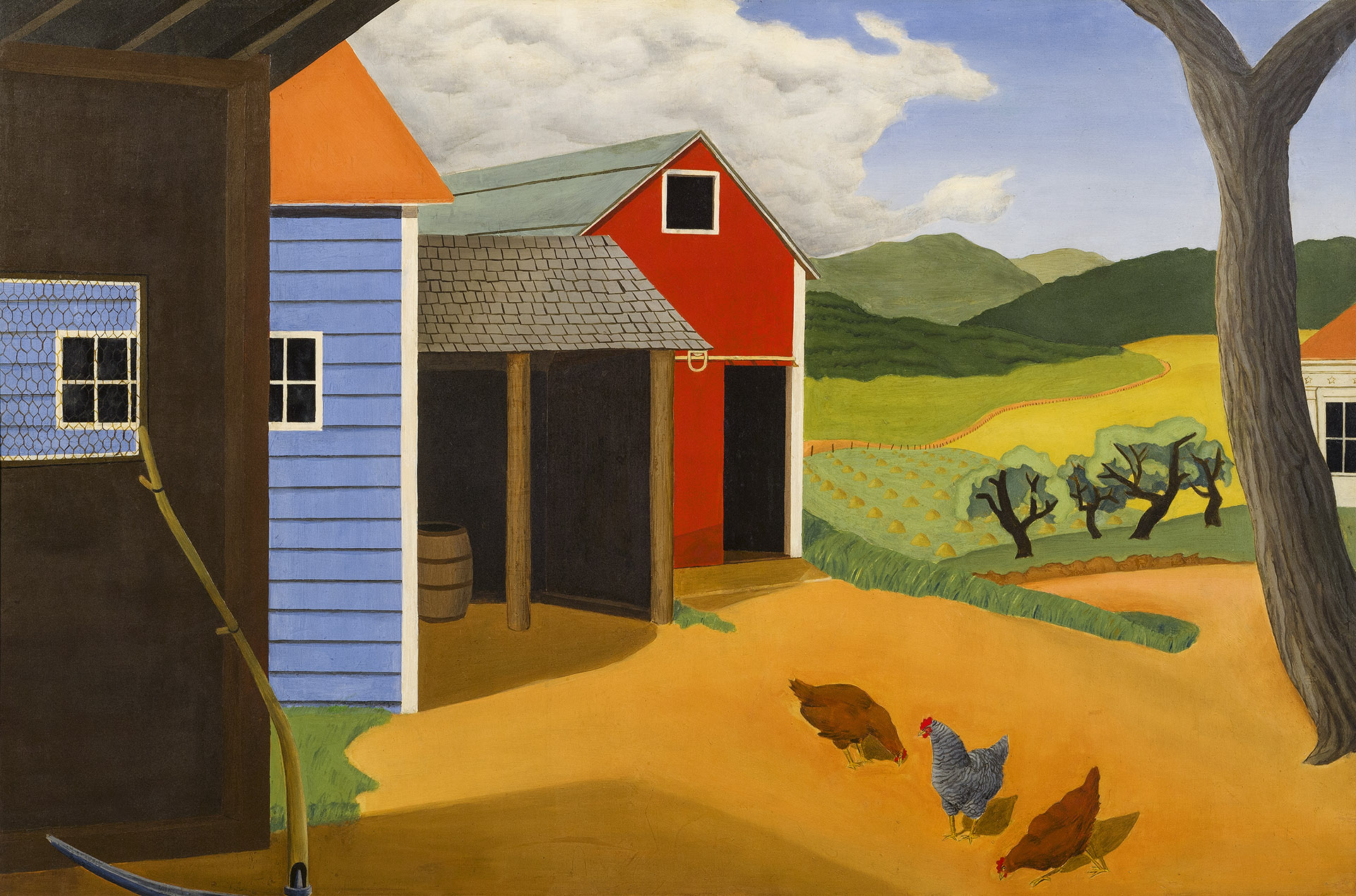

Driven by a desire to bring structure back to art -- a reaction to the formlessness that Impressionism had championed -- the Precisionists helped build the foundation of American Modernism. Inspired by Cubism’s fragmented compositions, photography’s experimental use of framing and lighting, Synchronism’s color harmonies, and the Italian Futurists’ reverence for modernity, the Precisionists adopted a crisp, clean style of representation that emphasized the geometric form and celebrated science and industry as assets to American culture. According to the exhibition essay by Deedee Wigmore, President of D. Wigmore Fine Art, “The Precisionist artists’ desire to find the structure underlying reality contributed to their focus on architectural and mechanical subjects.” From towering skyscrapers and sprawling factories to silos, grain elevators, and barns, the Precisionists turned to all forms of American architecture in order to establish this structure.

Though the Precisionists never formally organized or issued a manifesto, they began exhibiting together in New York at the Whitney Studio Club and the Charles Daniel Gallery during the 1920s. When the Charles Daniel Gallery, which represented Charles Demuth, Preston Dickinson, Charles Sheeler, Niles Spencer, Henry Billings, Peter Blume, Elsie Driggs, and Charles Goeller, closed in 1932, Edith Halpert’s legendary Downtown Gallery became the go-to place for Precisionism.

As the modern age rolled on, the vocabulary of the American art world changed rapidly, but the influence of Precisionism remained apparent. According to Wigmore’s essay, “a nationalism developed that desired an art with American subjects executed in a style capable of speaking to all Americans.” Soon, movements such as American Scene Painting, Social Realism, Magic Realism, and Surrealism took hold. Wigmore said, “Precisionism came to an end when the inspiration for a painting came from feelings rather than form. Surrealism began this and soon, a new American style developed -- Abstract Expressionism.”

The exhibition at D. Wigmore Fine Art explores the evolution of Precisionism, from its inception and development in the 1920s, to its influence on the Modernist movements of the 1930s and 1940s. In her essay, Wigmore writes, “Our exhibition aims to demonstrate that the continuation of Precisionism during the 1930s and 1940s can be identified in works maintaining both geometric forms and realistic representations of America in their subject matter.” The thirty works featured in Adapting Precisionism range from long-familiar, bucolic farm scenes by such artists as Allan Gould, Konrad Cramer, and Doris Lee, to O. Louis Guglielmi’s geometric cityscapes and Irene Rice Pereira’s near-abstract factory compositions. Together, these works draw connections between Precisionism and a range of modern movements, including American Scene Painting, Social Realism, Surrealism, and Constructivism.

Rather than being hung chronologically, Adapting Precisionism is organized thematically in groups of four or five paintings. According to Wigmore, “Each group has an architectural focus and reflects either an urban or rural setting. For instance, one group shows industry in a rural setting; another- the skyscraper and its inspiration, the grain elevator; and another- the convergence of folk art and architecture in abstracted compositions.” The biggest challenge, said Wigmore, “was organizing the exhibition into a narrative of evolution rather than revolution to help viewers understand the style’s outgrowth.”

Adapting Precisionism offers a sweeping and unexpected view of a hugely important, but often overlooked movement. By highlighting these pioneering works, Wigmore gives the Precisionists the recognition that they deserve and illustrates the important role that the movement played in bridging the gap between American realism and complete abstraction. Wigmore said, “I hope that the takeaway for viewers is that dozens of American artists who they have never heard of used an American-developed style called Precisionism to keep the door open for Modernism. Precisionism was about the search for architectural structure underlying reality, which eventually led American artists out of realism into pure geometric abstraction.”

Adapting Precisionism: 1925-1946 will remain on view at D. Wigmore Fine Art through July 31, 2015.