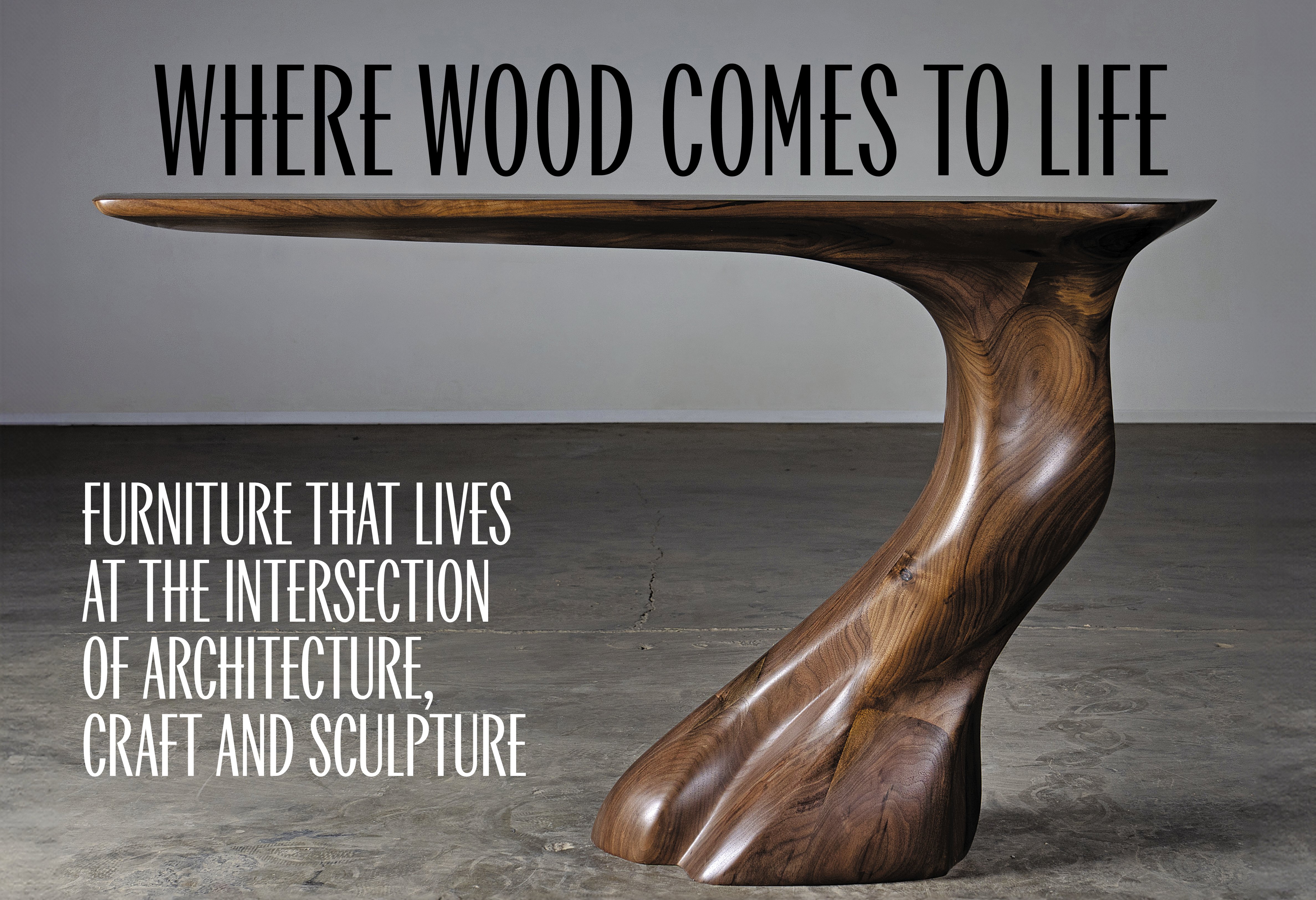

Where Wood Comes to Life: Furniture that Lives at the Intersection of Architecture, Craft and Sculpture

|

One of the most requested designs, the dramatic Frolic cantilevered console reveals fascinating wood grain swirling through its contours. |

by Benjamin Genocchio

All photos courtesy of Amorph unless otherwise noted

There is something animated, energetic, even warming about Amir Habibabadi’s biomorphic and amorphous furniture forms, which are eminently functional, yet futuristic, sculptural, and artist-driven.

Habibabadi is the creator behind Amorph, a boutique furniture brand and manufacturing company based in downtown Los Angeles. He is an architect by training and began making furniture prototypes in 2017, fresh out of SCI-Arc (Southern California Institute of Architecture in Los Angeles). “I loved architecture, but what excited me much more was creating unconventional, organic designs rather than following traditional styles,” he says. His years of academic study taught Habibabadi how to adapt computers and new industrial machinery for use in the design field. He started working with wood, which, he says, proved “perfectly suited” to creating the warm, organic forms he envisioned. He also experimented with casting pieces in bronze, but the process was expensive and time-consuming, and proved impractical for his highly customized workflow.

|

Amir Habibabadi |

His ambitious wooden forms quickly caught the attention of the design world. One of his earliest and most successful designs was the Gazelle dining chair, designed in 2017. “The idea was to create an elegant three-legged design that embodied the grace and beauty of a gazelle,” he says. “My focus was primarily on the back of the chair, as the front is often positioned against the table and isn’t as visible. From the outset, designers were constantly requesting these from me.”

|

The Agate console is a floating, wall-mounted design with hidden drawers for stashing secrets. |

Habibabadi has also done well with his gravity-defying, single-legged, cantilevered consoles, of which there are several different versions. Most popular has been the “Frolic” console table, with a distinctive tree trunk-like base, offered in solid walnut or ash in a wide range of stains. The “Aras” Console is another best seller, combining flowing curves with minimalist lines. “When installed, it looks like it is floating on the wall,” he says. Engineering was required to make each of these designs functional. “One of the challenges I had working on the Frolic console was to keep it stable,” he says. “It was a structural issue, because it’s not easy to build a console that stands on one leg but is fully balanced.” The base is engineered to be balanced with no weight inside. “I did it on a computer, then used a 3-D printer to make a small version just to check that it would stand up.”

Habibabadi says he is always thinking about how his designs can enhance interiors with unique and artful structures. “I want my pieces to stand out but also be functional.” He points to his Malva mirrors: “The frame here is not only holding the mirror inside a border, but it comes around and turns and invades the central space. Something cool happens as it turns, and that makes the experience of the mirror not only 2-dimensional but 3-dimensional on the wall.” Rooted in a deep passion for art and design, his work is fundamentally artistic — sculptural, expressive, and imaginative while embracing the utilitarian vision of an architect.

|

The Xena Cabinet’s rippling, fluid façade captures movement in form. |

|  | |

| Left: Hardware begone! A knot-form door handle emerges organically from the white oak door surface. Right: Amir has begun to experiment with custom architectural elements. This spectacular “spiderweb” staircase railing is a personal project in the designer’s home. | ||

|  | |

Left: Interior designer Nicole Hirsch juxtaposed warm, organic Chimera Stools against white lacquer cabinetry for an expansive waterfront residence in Boston’s Seaport area. Photo: Sarah Winchester Studios Right: The ever-popular Petra Console makes a bold impression in an entryway by R/Terior Studio, Los Angeles Photo: SEN Creative | ||

|  | |

Left: Amorph’s organic sculptural double doors installed at the late designer Amy Lau’s gallery and offices in the New York Design Center. Right: Custom-designed nightstands for Amy Lau’s bedroom, one of many projects on which they collaborated. Amir credits Amy with pushing his work to the next level. Photo: Thomas Loof | ||

Interior designers find this quality alluring and attractive. “Amir’s work is more than just furniture; it’s sculpture. From consoles to coffee tables to counter stools, every piece he has created for us transforms the room. I also appreciate the gorgeous wood stains and finishes he achieves, which is no easy feat. His pieces have brought such warmth and sophistication to our projects,” says designer Nicole Hirsch, based in Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Other designers share Hirsch’s admiration for the sculptural qualities of his work. “Amir’s work with Amorph strikes a chord with me because it comes from a place where architecture, craft, and sculpture intersect,” says furniture designer Tim Schreiber, who also trained as an architect. “You can feel that spatial intelligence in the way his pieces command a room: they transcend the notion of furniture altogether, emerging as focal points that define a space — pieces that capture attention instantly and set the tone for the entire experience through their bold presence and sculptural authority.” Schreiber also admires his craftsmanship. “Coming from a background as a cabinetmaker myself, I have always believed that the hand and the eye must remain close to the material, even when technology pushes us into new territories,” Schreiber adds. “Amir has a similar approach. His pieces are shaped by advanced digital processes, yet they never lose the tactile resonance of something handmade. Working in wood, his designs remain rooted in the designer’s vision rather than the machine’s limitations.”

|  | |

Left: The Agna Swivel Stool can be made in counter or bar height. Right: Graceful as its namesake, the Gazelle Chair was designed to be admired especially from the back. | ||

|

The Nala Bench has an open form that gives the seat a light, floating appearance. |

Habibabadi has a sort of love-hate relationship with wood, which he describes as “mercurial, full of surprises, good and bad.” The exterior of a slab, he explains, “very often doesn’t reveal what lies beneath.” But he has embraced this idiosyncrasy, which he now sees as giving every work “its own unique identity and individuality.” Working with wood also gives Habibabadi opportunities to collaborate closely with interior designers and explore unexpected iterations of his designs — recently, for example, he had a client ask him to adapt one of his cantilevered console tables into a long bench. “I never imagined something like that until they asked me.”

| |

With its unique, playful form, the Jolie Mirror is often used above a console in an entryway, where it makes a delightful first impression. |

Geometry is the template from which all his designs begin, and from there, he radically abstracts new shapes using advanced computer programs. Then he usually makes scale models in wood to check stability. Once he is satisfied with the design, a CNC machine cuts the final parts, which are then glued together to construct the piece. Next comes the time-consuming step of sanding the objects by hand to give the designs their sensual curves and rounded edges, before applying the finish coats of stain or lacquer. Habibabadi is known in the design industry for his fine lacquers and finishes — it is his trademark in a competitive industry. “The secret lies in hard work, specifically, the time-consuming hand techniques we use for our finishes. Also, the specialized materials, for example, we use auto body paint for our lacquers, which gives them a glossy and vibrant appearance.” He adds, laughing, “There is also some other, secret stuff I do, but I don't want to talk about that.”

Habibabadi handcrafts and finishes every one of his designs himself. It is a point of pride, he says. He believes part of being a successful maker today in the design world is having the ability to create and customize anything for clients. Everything he makes can be customized with colors and finishes, and custom dimensions. “I am driven to create one-of-a-kind, intricate pieces that spark curiosity — works that make people pause and wonder about the craft behind them, while commanding attention from the very first glance.” Habibabadi has a small team in his Los Angeles studio that performs various aspects of the process, including hand staining, polishing, grinding, and sanding to create the finished surface. His wife, Sarvenaz, works in the office, handling marketing and administrative responsibilities, and sometimes assists with small tasks in the shop. “She is an interior designer with wonderful taste, which brings an additional perspective to my designs.”

Amy Lau, the late New York interior designer, was an early fan, client, and mentor, he says. She commissioned custom pieces for many of her projects, purchased a pair of wavy-front nightstands from Habibabadi for her New York apartment, and a set of double doors for her gallery and office at the New York Design Center at 200 Lexington Avenue. They had begun planning a solo exhibition at her space in the New York Design Center for his new high-end design line, under Habibabadi's own name. “Amy was such an important person in my life and influential on my career,” Habibabadi says. “She admired my craftsmanship and felt that we could take it to the next level with a line of incredibly labor-intensive one-of-a-kind pieces that would really stand out in the market.” Habibabadi completed the designs and models, but with Lau’s passing, the show was canceled. He will be presenting a cabinet from the series this year at Design Miami in Miami with CASA AnKan gallery.

|

| Clockwise from top left: A biomorphic glass top reveals the hairpin curves and swooping lines of the Zen Coffee Table base, shown here in ebonized ash wood. The statuesque Roman Floor Lamp in ash with a saddle oak stain. The play of light and shadow on the organic form of Amorph’s Helen Table Lamp. The marble-topped Abbi Side Table will fit most anywhere – the perfect drink table. |

Habibabadi is still planning to launch his new line of higher-end designs. They are a more labor-intensive and extreme version of what he is doing, he says, with radically undulating surfaces made of new, experimental materials such as papier-mâché embedded in wood. “I am currently building a cabinet for the show in Miami. Each door takes me about 2 weeks to finish and sand. It is time-consuming, exacting work.”

Habibabadi sees the new designs as the more artistic part of his practice as a designer. The price point is higher because the designs are complex to execute and incur additional labor, particularly in the finishing processes. One of legendary designer Tapio Wirkkala’s carved wall installations from the 1960s, using bent plywood, serves as inspiration for the undulating curved surfaces of the new cabinet he is working on. “Tapio Wirkkala used plywood that at the time was also used for aircraft bodies, celebrating the glue lines of the plywood as an additional pattern on the surface,” he says. Habibabadi created his own type of plywood by combining white oak with colored paper. “It allows me to introduce color and also play with surface textures. By gradually changing the color of the papers, I can get an ombré surface effect.” He has also begun working on a new line of sculptural wooden doors. The design features elegantly integrated sinuous handles that emerge organically from the door slab. “They illustrate how my work is expanding beyond furniture design into architectural elements. While I’ve designed only two doors so far, my goal is to shape features that seamlessly merge form and function — pieces that are not just functional but are architectural statements, carrying the language of my furniture into the built environment.”