Dietrich American Foundation: The Gottschall Family of Fraktur Artists

|

by Lisa Minardi

| |

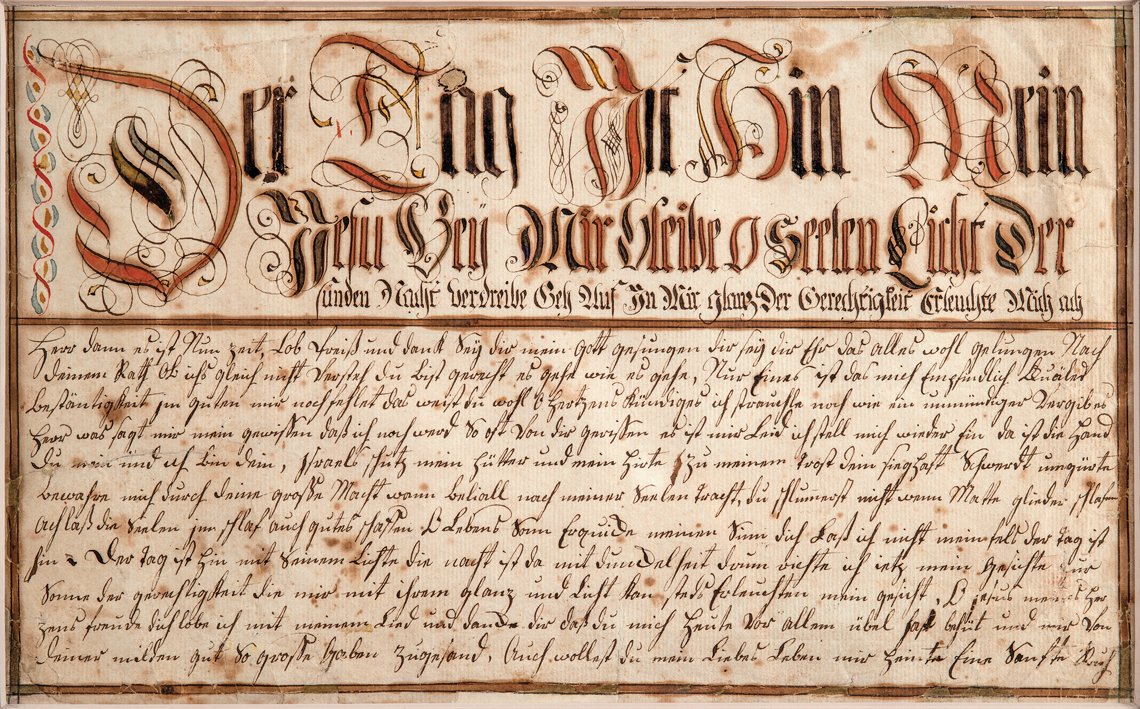

Fig. 1: Religious text attributed to Jacob Gottschall (1763–1845). Skippack Township, Montgomery County, Pa., ca. 1795. Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 13 x 8⅛ inches. The Dietrich American Foundation (7.9.HRD.342). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Pennsylvania German art is one of the largest portions of the Dietrich American Foundation’s collection. Representing the breadth of artistic and religious traditions of German settlers in southeastern Pennsylvania, these objects had a highly personal appeal to founder H. Richard Dietrich Jr., due in part to his own ancestry. In 1767, German immigrant Adam Dietrich arrived in Philadelphia on the Britannia. By 1779, he was a prosperous farmer and landowner in Berks County, Pennsylvania. Two hundred years and seven generations later, his descendant H. Richard Dietrich Jr. began to collect Pennsylvania German decorative arts. Today the Dietrich American Foundation owns more than 125 examples of Pennsylvania German fraktur, or decorated works on paper, in addition to furniture, woodcarvings, and paintings made by some of Pennsylvania’s most talented German-speaking craftsmen. Thanks to a partnership between the Foundation and Historic Trappe, many of these objects are now on view at the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies in Trappe, Pennsylvania. The Center will re-open to the public later this year following a year-plus closure for COVID-19 and building renovations; visit HistoricTrappe. org for more information.

Historic Trappe is located in the scenic Perkiomen Valley region of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, settled in the early-to-mid 1700s by diverse groups of Pennsylvania German immigrants including Lutherans, German Reformed, Dunkards, Mennonites, and Schwenkfelders. The area is noted for its agricultural and industrial heritage, with abundant streams and forests that supported a number of early milling operations, tanneries, and ironworks. Its artistic legacy is equally noteworthy, including outstanding examples of fraktur, redware pottery, painted and inlaid furniture. This article highlights the work of the Gottschall family of fraktur artists.

|

Fig. 2: Vorschrift (writing sample) signed by Martin Gottschall (1797–1870). Franconia Township, Montgomery County, Pa., ca. 1815–1818. Watercolor and ink on laid paper, 7¾ x 12¾ inches. The Dietrich American Foundation (7.9.1360). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

THE GOTTSCHALL FAMILY

| |

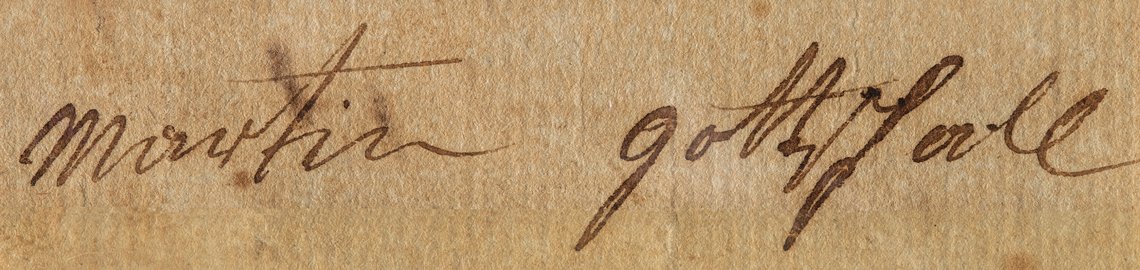

Fig. 3: Signature of Martin Gottschall on verso of the fraktur illustrated in figure 2. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Two generations of Mennonite schoolmasters-turned-farmers in the Gottschall family produced some of the most visually striking and iconic examples of Pennsylvania German fraktur.1 The earliest example in the Dietrich collection is a spectacular drawing with a profusion of flowers along with two large, colorful peacocks and a pair of women in striped dresses (Fig. 1). Made by Jacob Gottschall (1769–1845), this fraktur is one of the few known examples of his artwork to survive. Born in New Britain Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, Jacob Gottschall was named after his great-grandfather Jacob Gaedtschalk (1670–1763), who emigrated from Germany in 1702 and was ordained by the Germantown Mennonite meeting as the first Mennonite bishop in America. In 1780, Jacob Gottschall (age eleven) was a student of Johann Adam Eyer (1755–1837) at the Perkasie school. Eyer was a talented fraktur artist whose work influenced generations of students who learned to copy both his artwork and handwriting. Jacob Gottschall was surely one of Eyer’s most talented protégés; the boldly drawn peacocks with elongated necks and tails on this fraktur echo birds on fraktur made by Eyer. This drawing likely dates to about 1792, when Jacob Gottschall (then twenty-three years old) began to teach school at the Skippack Mennonite meetinghouse. The fraktur was likely made for one of his students; it descended in the Nice family of Skippack Township. The text at the bottom of the fraktur encourages readers to decorate themselves simply in Christ—in contrast with the gaily adorned female figures flanking the text—and alludes to the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (Matthew 25:1–13), in which only the five wise virgins who took oil with them to refill their lamps were admitted to the kingdom of heaven. The five foolish virgins who brought only their lamps had to go in search of more oil and were left out.

Jacob Gottschall’s tenure as a schoolmaster and fraktur artist was short-lived. In 1795, he married Barbara Kindig and they settled near Morwood in Franconia Township, Montgomery County. In 1804, Jacob became a minister for the Franconia Mennonite congregation and in 1813 a bishop. Together he and Barbara raised eleven children—including two sons who followed in their father’s footsteps and became schoolmasters and fraktur artists. Unlike their father, however, the brothers remained steadfast bachelors.

Martin Gottschall (1797–1870) was the second child of Jacob and Barbara Gottschall. He likely taught at the Salford Mennonite meetinghouse school from 1815 to 1818, based on a series of Vorschriften, or writing samples, made during those years that are thought to be his work. Only one signed example is known, which was acquired by the Dietrich American Foundation in 2017 (Fig. 2). Typical of the Vorschriften form, the fraktur begins with several lines of ornate German Fraktur lettering before transitioning to German script for the rest of the text. It lacks the usual alphabet and numeral systems that were typically included at the bottom; these pieces were often given to children who were learning to write so that they could practice copying the letters. The fraktur is signed on the back in German script by Martin Gottschall (Fig. 3). Fraktur are rarely signed, making this example an important clue that will enable future researchers to identify additional examples of Martin Gottschall’s work.

|

Fig. 4: Drawing of three women attributed to Samuel Gottschall (1808–1898), Franconia Township, Montgomery County, Pa., 1835. Watercolor and ink on wove paper, 6 x 8½ inches. The Dietrich American Foundation (7.9.HRD.1791). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Eleven years younger than Martin, Samuel Gottschall (1808–1898) was the eighth child of Jacob and Barbara Gottschall. Samuel taught at the schoolhouse erected on his father’s property during the mid-1830s—coinciding with his production of fraktur, most of which is dated 1834 or 1835. The Dietrich American Foundation owns three examples of his work, all dated 1835. The best-known example is a striking drawing of three women (Fig. 4) that reflects a clear familiarity with the earlier work done by Jacob Gottschall in the 1790s. While both father and son drew the women in vertically striped dresses and with hands on their hips, Samuel Gottschall’s women are rendered in astonishingly bold fashion, with thick black outlines that provide a sharp contrast against the paper background. This piece exemplifies Samuel’s use of jewel-tone pigments and his technique of “pooling” the watercolors to create a mottled effect. He also used a thick binder, probably gum arabic, which over time gives a shiny, crystalline look to the colors.

|  | |

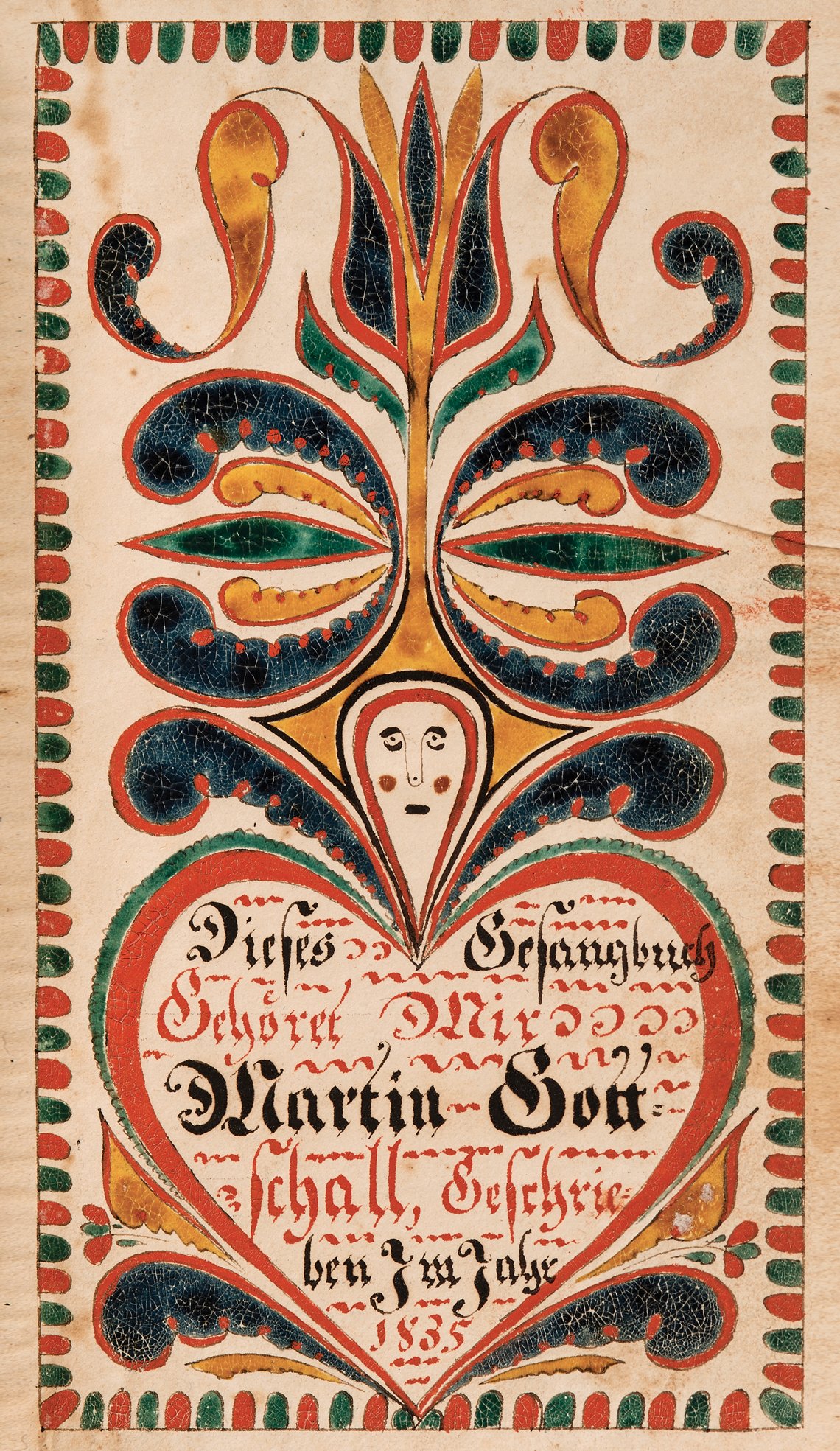

(left) Fig. 5: Bookplate for Martin Gottschall attributed to Samuel Gottschall (1808–1898). Franconia Township, Montgomery County, Pa., 1835. Watercolor and ink on wove paper, 6¼ x 3¾ inches. The Dietrich American Foundation (7.9.1323). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. (right) Fig. 6: Religious text attributed to Samuel Gottschall (1808–1898). Franconia Township, Montgomery County, Pa., 1835. Watercolor and ink on wove paper, 6½ by 4¼ inches. The Dietrich American Foundation (7.9.1294). Photo by Gavin Ashworth. | ||

| |

Fig. 7: The Seven Rules of Wisdom, attributed to Samuel Gottschall (1808–1898). Franconia Township, Montgomery County, Pa., 1834. Watercolor and ink on wove paper, 12½ x 7½ inches. Historic Trappe (2020.016.0005). Photo by Michael E. Myers. |

Some of Samuel Gottschall’s fraktur art was made for family members rather than his pupils. He may have kept the drawing of three women for himself, as it remained in the Gottschall family until 1998, when the foundation acquired it from descendant Katharine Steele Renninger (1925–2004), a noted Bucks County artist. Samuel Gottschall also produced a number of bookplates, including one for his brother Martin (Fig. 5). Made for a hymnal printed by Michael Billmeyer of Germantown in 1811, the bookplate is decorated with an abstract face and tulip springing from a heart that is inscribed (translation): “This songbook belongs to me Martin Gottschall, written in the year 1835.” One of Samuel Gottschall’s last known fraktur is a religious text that he produced on November 18, 1835 (Fig. 6). Above the date, he inscribed it with a grim rhyme: “Bey aller deiner Freud und Lust, Gedenke dass du sterben Must” (translation): “Amid all your joy and pleasure, remember that you must die.”

Samuel Gottschall was also a weaver; his account book covering the period from 1830 to 1836 survives and documents that he produced linen, tow (a coarse linen), and woolen cloth. In 1838, he gave up both teaching and weaving to embark on a new, more lucrative pursuit—milling. Samuel erected a sawmill along the Branch Creek, which flowed through a property in Franconia Township that he co-owned with his brother William Gottschall. Two years later, Samuel added a clover mill and in 1842 he built a house and barn. He evidently prospered, as in 1879 he encouraged the establishment of the Souderton Mennonite congregation and donated both a house and two rows of horse sheds to serve the meetinghouse.

An earlier example of Samuel Gottschall’s work, dated 1834, was recently donated to Historic Trappe and will be on view later this year at the Center for Pennsylvania German Studies (Fig. 7). It is entitled Die Sieben Regeln Der Weisheit (The Seven Rules of Wisdom) in reference to Proverbs 9:1 “Wisdom has built her house, she has hewn out her seven pillars.” Formerly in the collection of antiquarian and author Cornelius Weygandt of Germantown, Pennsylvania, this unusual example of Samuel Gottschall’s work incorporates design motifs found in his more typical fraktur within a grid consisting of seven horizontal rows and five vertical columns.

The Gottschall family produced an exceptional body of fraktur art that continues to astonish and delight viewers today. Additional examples of their work are in the collections of the American Folk Art Museum, Free Library of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Mennonite Heritage Center in Harleysville, Pa., and the Schwenkfelder Library & Heritage Center in Pennsburg, Pa.

The Dietrich American Foundation and Historic Trappe’s Center for Pennsylvania German Studies will present an occasional series of articles in these pages, featuring new research on objects made in southeastern Pennsylvania from the Dietrich collection. This article is the fifth in a series featuring the Dietrich American Foundation’s collection. The Dietrich American Foundation is delighted to present these articles as a type of crowd sourcing exercise, where responses and information shared by readers can inform the research. New information gleaned will be provided over the course of the series. As is always the Foundation’s mission, we are excited to share findings and stories about people, places, and history that are revealed through our research. Contact details are in the author bio below. For information about the Dietrich American Foundation, visit dietrichamericanfoundation.org.

1. On the Gottschall fraktur artists, see Mary Jane Lederach Hershey, This Teaching I Present: Fraktur from the Skippack and Salford Mennonite Meetinghouse Schools, 1747–1836 (Intercourse, Pa.: Good Books, 2003), 107–110, 112–113, 146–154, 170–171. See also Clarke Hess, Mennonite Arts (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 2002), 113, 122–123.

Lisa Minardi is the executive director of Historic Trappe and a contributing author to In Pursuit of History: A Lifetime Collecting Colonial American Art and Artifacts, ed. H. Richard Dietrich III and Deborah M. Rebuck (Yale University Press for the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Dietrich American Foundation, 2019). Please send comments/queries to info@historictrappe.org.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|