Edward Hopper Hours of Darkness

|

|

any of Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) most admired paintings are night scenes. An enthusiast of both movies and the theater, he adapted the device of highlighting a scene against a dark background, providing the viewer with a sense of sitting in a darkened theater waiting for the drama to unfold. By staging his pictures in darkness, Hopper was able to illuminate the most important features while obscuring extraneous detail. The settings in Night Windows, Room in New York, Nighthawks, and other night compositions enhance the emotional content of the works —adding poignancy and suggestions of danger or uneasiness.

The Nyack, New York, born Hopper trained as an illustrator before transferring to the New York School of Art, where he studied under Ashcan School painter Robert Henri (1869–1929). Near the beginning of his career, he revealed an interest in night scenes. On his first trip to Europe in 1906–07, he was fascinated by Rembrandt’s Night Watch (1642) in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam; writing to his mother that the painting was “the most wonderful thing of [Rembrandt’s] I have seen, it’s past belief in its reality — it almost amounts to deception.” In several early paintings, Hopper depicted rooms and figures in moonlight. Thereafter, he showed scenes illuminated by artificial light.

Painting darkness is technically demanding, and Hopper was constantly studying the effects of night light. Emerging from a Cape Cod restaurant one evening, he remarked upon observing some foliage lit by the restaurant window, “Do you notice how artificial trees look at night? Trees look like theater at night.”1

Contemporary critics recognized both the theatrical settings of Hopper’s paintings and the challenge of painting night scenes. In reviewing an exhibition that included Drug Store and Night Windows, New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell exclaimed, “How brilliantly Hopper lights his stage!”2 A Chicago journalist declared that Hopper’s Night Windows “is interesting as composition and as an experiment in that difficult feat, the painting of nuances of night light.”3

Hopper’s greatest night scenes, Nighthawks, Automat, and Office at Night, considered icons of American art, are included in an exhibition that concentrates on Hopper’s work between the two world wars, the period of his greatest achievement. On view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through August 19, 2007, the show will then travel to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Art Institute of Chicago.

|

|

Night Shadows, 1921. |

In the 1910s Hopper turned to etching and achieved his first success. His prints were purchased by collectors, earned critical acclaim, and won prizes in exhibitions. Striving for strong dark-light contrasts, he used the whitest paper he could buy locally and sent to London for intense black ink not found in the United States. Prints such as Night on the El Train, Evening Wind, Night in the Park, and particularly Night Shadows, were among his most sought-after etchings. Both the deep darkness and the unusual viewpoint create dramatic tension in Night Shadows. A solitary figure in an unidentified city walks toward the shadow of an unseen lamp post. The possible danger lurking in the darkness, the barrier-like shadow across his path, and the isolation of the figure lend an ominous air to the image.

|

|

Night Windows, 1928. |

The majority of Hopper’s nocturnes depict New York City. In Night Windows he created a view through a window into a neighboring apartment, which suggests a scene on an illuminated stage watched by an audience in a darkened theater. The woman in her pink chemise stoops in a rather inelegant pose, unaware that she is being observed—a theme appropriated from Degas, an artist Hopper admired. A breeze blows a curtain through the window on the left. A contemporary critic explained the appeal of the painting: “It is one of those glimpses into other lives which one suddenly catches from the window of a passing El, and it crystallizes superbly that momentary sense of the mystery and intensity of the thousands of lives pressing close to each other, all oblivious to the revelations of undrawn blinds, which spell New York more than the soaring spires of skyscrapers.”4

|

|

Room in New York, 1932. |

In Room in New York, a man, dressed in business attire, appears to have just come home from work. Having removed his jacket, he settles in his chair to read the newspaper. In contrast, the woman wears evening clothes; her listless gesture indicating boredom. The gulf between the figures is further indicated by a closed door in the wall behind them, and tension is amplified by the claustrophobic setting. Hopper seems to be “on the verge of telling a story,” as John Updike put it, but the story has no obvious outcome, and the artist, in his description of the painting, remained noncommittal: “The idea was in my mind a long time before I painted it. It was suggested by glimpses of lighted interiors seen as I walked along city streets at night, probably near the district where I live (Washington Square) although it’s no particular street or house but is really a synthesis of many impressions.”5

|

|

Office at Night, 1940. |

A voluptuous secretary and her handsome young boss work overtime in an otherwise deserted office. The secretary’s heavy make-up, tight dress, and pose emphasize her sexual availability. She seems poised to pick up the paper that has fallen to the floor and to initiate some contact with her boss, but he ignores her, resolutely concentrating on the papers he holds. The night breeze blowing the window shade provides the only movement in the scene. Although the two figures are linked by the patch of light cast by the street lamp onto the wall, their future interaction is uncertain. The unresolved drama of Hopper’s scene resonated with contemporary viewers still adjusting to the presence of women in the workplace.

|

|

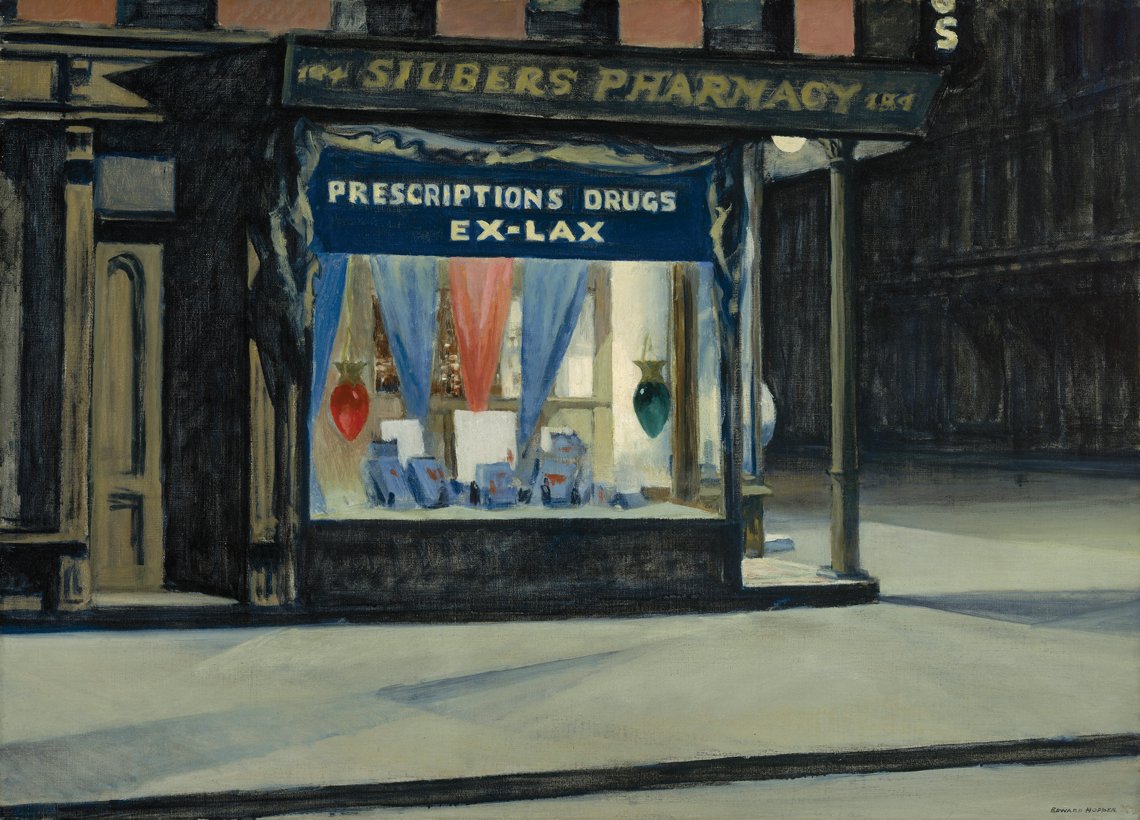

Drugstore, 1927. |

This night scene with its deserted, shadowy streets intersected by the brightly-lit, colorful window of Silber’s Pharmacy, is compelling, despite the absence of people. Hopper’s inclusion of the advertisement for Ex-Lax seemed indelicate to some. The lamp near the drug store’s corner entrance casts triangular shadows on the sidewalk. The drug store window, with its red and blue bunting and red and green vessels filled with colored water, provides welcome illumination against the inhospitable darkness. Drug Store seems a stage set on which the viewer might project his own drama. Fifteen years later, Hopper reprised the composition in Nighthawks, adding an intriguing cast of characters. The same empty streets, wedge-like building forms, glowing interiors, reflections of light on the sidewalk, and commercial advertisements produce an unsettling effect in both paintings.

|

|

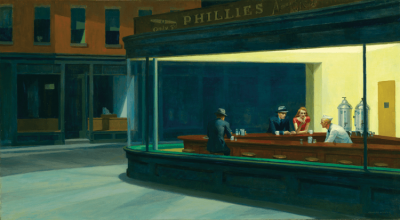

Nighthawks, 1942. |

Hopper created his masterpiece, Nighthawks, in the six weeks following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He explained that Nighthawks “was suggested by a restaurant on Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet. Nighthawks seems to be the way I think of a night street … I didn’t see it as particularly lonely. I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”6 A committed realist, Hopper made seventeen preparatory sketches of the coffee urns, the objects on the counter, and the figures, using such details to make the scene more persuasive. The four figures taking refuge in the brilliantly lit diner seem to exist in uneasy relation to one another — Hopper gives no indication of why they are there or what brought them together. The counterman appears to be addressing the man next to the woman dressed in red. The nighttime setting intensifies the evocative mood of the painting and the ambiguity of the drama.

|

|

Gas, 1940. |

In September 1940, Hopper’s wife, Jo, wrote to his sister Marion, “Ed is about to start a canvas—an effect of night on a gasoline station.” Gas, which Hopper painted in his Truro, Massachusetts, studio, was one of his few night scenes set in the country. Not finding any one filling station to his liking, he made studies of several stations and combined them. Fellow artist Charles Burchfield admired Hopper’s choice of titles, “so provocative in their terseness … Gas, to a less discerning artist, would have come out as Gas Station or Gas Station Attendant. The solitary word ‘gas’ seems to express the whole impact of that commodity on American life.”7 In fact, Hopper’s paintings do reflect the changes that the automobile was making in rural America, as roads, gas stations, and motels were built across the country. His primary aim, however, was to explore the effects of artificial light at dusk. Light streams out of the station house illuminating the three gas pumps. The lamp on the Mobil Gas Company Pegasus sign casts pools of light on the ground and nearby tree. The brightly-lit station seems a last welcoming oasis along a road to impenetrable darkness.

|

|

Rooms for Tourists, 1945. |

Although Hopper generally created his night pictures by combining his observations of several scenes, Rooms for Tourists is a portrait of a single place, an inn in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Its mellow atmosphere is a departure from the unsettling mood of many of Hopper’s night scenes. He produced the painting from sketches made over several evenings working by the dome light in his parked car. He told a reporter, “Mrs. Hopper thought I should let the landlady know what I was doing out there, but I didn’t want to intrude.”8 Hopper had first painted this type of unprepossessing vernacular architecture in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in the 1920s, when he depicted the architectural details of dwellings, usually in brilliant sunlight. Here, he returned to the subject and set himself an especially complex pictorial challenge: to render the inn at night.

This article was associated with an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Art's Boston, Edward Hopper, on view from May 6–August 19, 2007; it was also on exhibit at the National Gallery of Art from September 16, 2007–January 21, 2008, and then at the Art Institute of Chicago from February 16–May 11, 2008.

1. Brian O’Doherty, “Portrait: Edward Hopper,” Art in America 6 (1964): 80.

2. Edward Alden Jewell, “Group of Five and Other Art Shows Visited,” New York Times, section 10 (January 27, 1929): 19.

3. Inez Cunningham, Chicago Herald and Examiner (Nov. 12, 1932), quoted in Half a Century of American Art, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1939, exh. cat., p. 24.

4. Mary Morsell, “Hopper Exhibition Clarifies a Phase of American Art,” The Art News 32 (Nov. 4, 1933): 12.

5. Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: A Catalogue Raisonné, vol. 3 (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with W. W. Norton, 1995), 220–221.

6. Katharine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice (New York: Harper& Row, 1960), 134.

7. Charles Burchfield, “Hopper: Career of Silent Poetry,” Art News 49 (March 1950): 17.

8. “Traveling Man,” Time (January 19, 1948): 59.

Janet L. Comey is a curatorial research associate in the department of Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Art, Boston.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|