Glassmaking America’s First Industry

Winter Antiques Show Loan Exhibition Corning Museum of Glass

|

|

By Jane Spillman

The Corning Museum of Glass has the largest and most comprehensive public collection of American glass in existence, with more than 20,000 pieces ranging in date from the mid-eighteenth century to the present day. Unlike cabinetmaking and silversmithing, glassmaking did not prosper during the first two centuries of American settlement, primarily because glassmaking required three types of knowledge and skill: the ability to construct a furnace that could maintain a temperature of at least 2,300 degrees; a knowledge of glass recipes; and proficiency in glassblowing; capabilities rarely found in a single person. Sand and other raw ingredients, ceramic pots for melting these materials, and wood for firing the furnace were additional necessities that were easier to obtain. Because the east coast of America was heavily forested, the colony’s London financiers were prompted to erect a glasshouse at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1608. The glasshouse failed twice and was then abandoned. Although no description of the glass survives, we know that samples were sent back to London.

|  | |

Left, Fig. 1: Wine bottle with seal of Richard Wistar. Wistarberg Glassworks, Salem County, N.J., ca. 1745–1755. Blown. H. 9.3 in. Gift of Miss Elizabeth Morris Wistar, 86.4.196. Richard Wistar was the son of Caspar Wistar who started the glasshouse in 1739. He inherited his father’s responsibilities in 1752 and operated the factory until it was closed in 1780. The glasshouse specialized in the production of bottles, although it also made window glass and a few tablewares. Right, Fig. 2: Covered tumbler engraved with Tobias and the angel. New Bremen Glassmanufactory of John Frederick Amelung, Frederick, Md., 1788. Blown, engraved “Happy is he who is blessed with Virtuous Children. Carolina Lucia Amelung. 1788.” OH.11.9 in. 55.4.37. This tumbler was a gift to Amelung’s wife, Carolina Lucia. It illustrates the story of Tobias, from the apocryphal Book of Tobit, who is guided by an angel as he carries the fish that will cure the blindness of his father, Tobit. The shape is of German origin, and the glass was undoubtedly intended for display, not for regular use. | ||

After several other false starts, the first successful colonial glasshouse was built by Caspar Wistar in Salem County, New Jersey, in 1739 (Fig. 1).1 Windows and bottles were regarded by early settlers as the most important glass products. Glass tableware was a luxury and could be imported from England and the Continent. Several other glasshouses were started during the eighteenth century, but the British discouraged manufacturing, preferring that the colonies should supply raw materials to the mother country and then purchase the resulting goods. Wistar’s factory operated almost sub rosa, as did two others in operation in eastern Pennsylvania just before the American Revolution. The new nation promoted manufacturing, causing the glassmaking industry to expand rapidly in the nineteenth century.

The earliest glasshouse in the new United States was the New Bremen Glassmanufactory in Frederick, Maryland, founded in 1785 by John Frederick Amelung, a skilled glassmaker who had emigrated from Germany along with other glass workers who brought their families and equipment with them. Although Amelung’s business went bankrupt in 1796, quite a few pieces that can be attributed to his glasshouse survive. He produced a number of signed glasses (Fig. 2), and several of his unsigned engraved objects are easily recognizable.

Glassmaking crossed the Allegheny Mountains in 1797, when Albert Gallatin (later President Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of the treasury) started the first glasshouse in western Pennsylvania. One of the most successful and longest-lived factories in Pittsburgh was operated by the Bakewell family and their several partners between 1808 and 1882. Bakewell, Page and Bakewell was arguably the most important of the Midwestern glasshouses. The first flint glass factory in the United States, it made a wide selection of tablewares (Fig. 3) and containers. In 1818, the Bakewell glasshouse filled President James Monroe’s order for a set of glassware, and it also produced a service for President Andrew Jackson.

|

Fig. 3: Footed bowl, Bakewell, Page and Bakewell, Pittsburgh, Pa., ca. 1815–1835. Mold-blown, with applied foot; engraved in three-leaf and daisy pattern. D.9.7 in. 94.4.9. The mold provided the shape of the bowl and the panels on the base; the glassblower then applied the funnel foot. The engraved pattern is believed to be unique to the Bakewell glasshouse and can be found on nearly two dozen sugar bowls, creamers, celery vases, and lamps. |

To make it more quickly and inexpensively, glass began to be blown into full-size, multipart metal molds that gave both pattern and shape to the finished object. This was a technique that had been developed by the Romans, but had fallen out of use in medieval times until it became popular again in the early nineteenth century. Chiefly employed for bottles and flasks, the method could also be used for patterned tablewares. Whiskey flasks with decorative patterns (Fig. 4) were extremely popular from about 1815 to 1850. More than six hundred designs of whiskey flasks made by various glasshouses have been catalogued and are eagerly sought by collectors today.

It was not until the 1820s, when the idea of mechanically pressing glass into molds was conceived, that the American glass industry achieved its greatest success. We do not know who first patented this process, but patents for improvements to the technique were granted to several glassmakers, including Deming Jarves of the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company (Fig. 5).

|  | |

Left, Fig. 4: Flask with portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette on one side, Stebbins and Stebbins, Coventry, Conn., 1824–1825. Blown in full-size mold. H.7.3 in. 60.4.87. This flask was undoubtedly made during Lafayette’s triumphal tour of the eastern United States in 1824–1825. The marks “S. & S.” and “COVETRY/CT” give us the name of the glasshouse. The fact that the company continued to use the mold even though the glassmaker misspelled the name of the city underscores the expense involved in its making. Hundreds of identical flasks could be blown in the same mold quite rapidly. Right, Fig. 5: Candlestick. Boston and Sandwich Glass Company, Sandwich, Mass., 1829–1830. Mold-blown stem; applied foot made from a pressed toddy plate. H. 8.7 in. Purchased in part with funds from the Gladys M. and Harry A. Snyder Memorial Trust, 2007.4.34. This candlestick matches a drawing made by Deming Jarves in a letter to his factory superintendent, in which he suggested making candlesticks with pressed bases. Pressing was then a new technique, initially employed in the manufacture of furniture knobs, small plates, lamp bases, and other flat pieces. The technology developed rapidly and within a year it was being used to make very elaborate objects. | ||

|

Fig. 6: Tableware in the “Comet” pattern, Boston and Sandwich Glass Company, Sandwich, Mass. and M’Kee & Brother, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1860–1870. Pressed. OH. (tallest) 13.7 in. Gift of E. S. Chace, 68.4.12–.23. This pattern, whose name may refer to the mid-nineteenth-century appearance of the Swift-Tuttle comet, is illustrated in the 1860 M’Kee trade catalogue. Models were found at Sandwich, indicating that it was probably made in both factories and perhaps in other glasshouses as well. The pattern seems to have been very popular and many examples survive. |

The glass pressing process spread quickly. In 1829, English writer James Boardman attended an exhibition of American manufactured goods in New York City. In his America, and the Americans (London, 1830), he commented “the most novel article was the pressed glass which was far superior, both in design and execution, to anything of the kind I have ever seen in London or elsewhere. The merit of its invention is due to the Americans and it is likely to prove one of great national importance.” Boardman’s prophecy would prove accurate. The pressing industry continued to grow rapidly, permitting American makers of glass tableware to compete successfully with European manufacturers. By the 1840s, many shapes and patterns were being produced, and housewives were being persuaded that they needed matching sets of table glass (Fig. 6). Following the introduction of natural gas as a furnace fuel in the 1870’s, the production of pressed glass tableware increased markedly in Ohio and western Pennsylvania.

Throughout the Northeast, the main centers of production were in southern New Jersey, upstate New York, and New England. The glass was brownish or greenish in color (for bottles) and pale aqua (for windowpanes). Blowers in the window and bottle glass industries were permitted to make pieces to sell or to take home at the end of their shifts (Fig. 7).

|

Fig. 7: Sugar bowl and cream pitcher. Redford Glass Company or Redwood Glass Works, N.Y., 1835–1850. Blown, with applied decoration; coins enclosed in stems. H. (sugar bowl), 10.7 in. (pitcher) 6.5 in. 55.4.157, 131. Each stem encloses a silver U.S. half dime. The coin in the creamer is dated 1829, and that in the sugar bowl is dated 1835. There is another 1829 coin in the hollow knop of the sugar bowl’s lid. The Redford Glass Company, near Plattsburgh, New York, and the Redwood Glass Works, near Watertown, New York, were in operation from 1831 to 1852 and from 1833 to 1877, respectively. Both factories made window glass and were started by John S. Foster, an experienced glasshouse superintendent. This pair of objects was probably made by a glassblower on his own time as a gift for his mother or wife. The dates on the coins may indicate a birthday or anniversary. |

|  | |

Left, Fig. 8: Kerosene parlor lamp. T. G. Hawkes and Company, Corning, N.Y., 1890–1900. Blown, cut. H. 24.7 in. Gift of Helen Chambers in memory of Marvin W. Chambers, 82.4.9. Thomas G. Hawkes (1846–1913) came from Ireland to New York City in 1863 and moved to Corning five years later, where he started his own successful glass cutting firm in 1880. The firm, which was in business until 1962, was not associated with a glasshouse, instead, it designed and cut blanks purchased from various places. This lamp, with a nonmatching chimney, is shown in the second edition of the Hawkes’ sales brochure, produced around 1900, where it is labeled as cut in the “Odd” pattern. In the late nineteenth century, many homes had an expensive lamp in the center of the parlor table, where at night the family gathered around it to read. Right, Fig. 9: Burmese lamp, Mt. Washington Glass Company, New Bedford, Mass., about 1885–1895. Blown, enameled. H.19.1 in. Gift in part of William E. Hammond, 79.4.91. Exotic names for decorative glass were popular in the late nineteenth century. The Mt. Washington Glass Company named the elaborate coloring of this glass Burmese, even though it was in no way related to that country. | ||

|

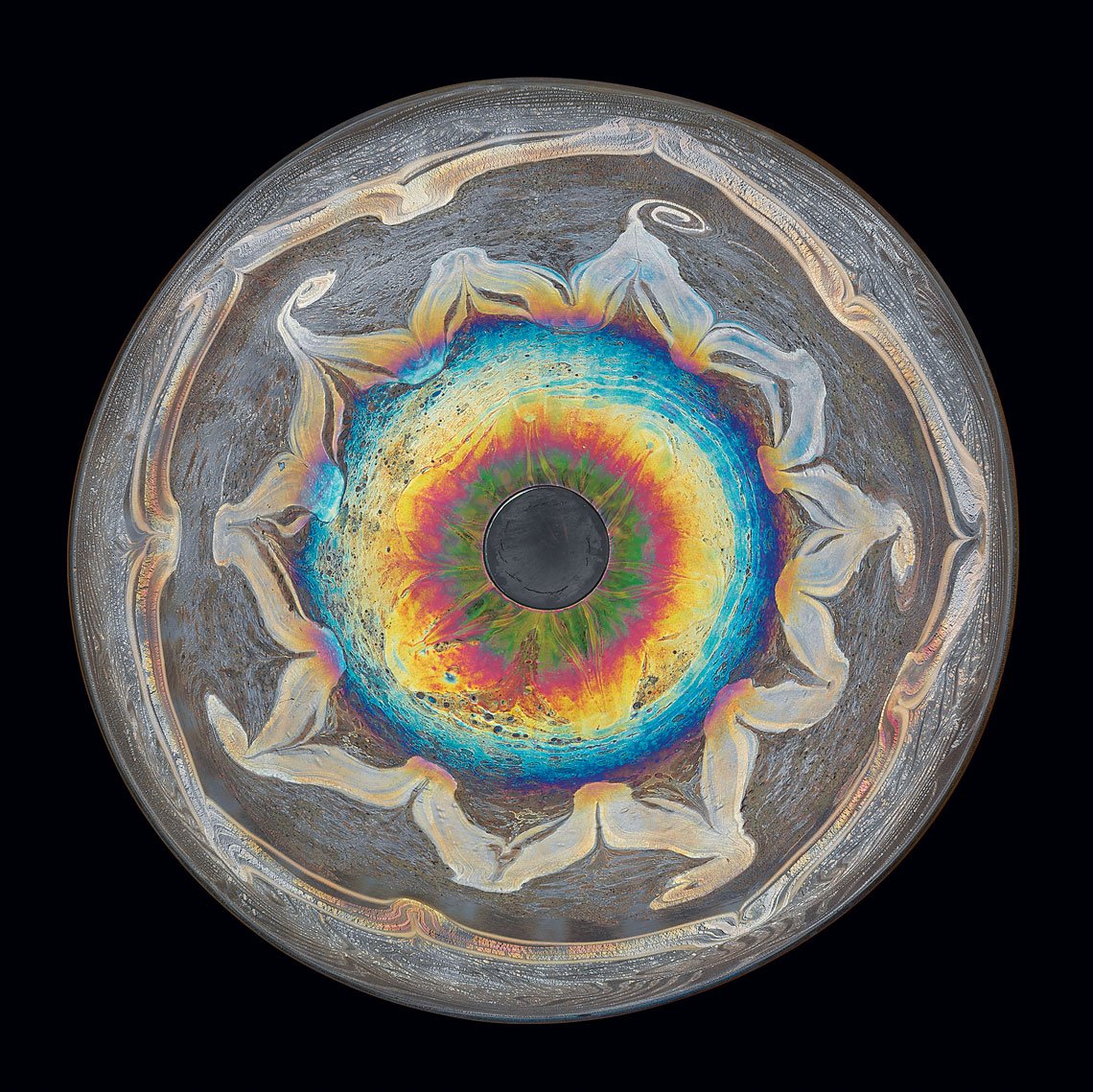

Fig. 10: Cypriote plaque. Tiffany Studios, Corona, N.Y., about 1896. Blown. D. 17.6 in. 2006.4.160. Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) developed the use of opalescent glass in stained glass windows, winning a prize at the 1889 world’s fair in Paris, where he displayed them. In 1893, Tiffany began to make blown glass objects, creating designs in iridescent glass that were very influential. |

| |

Fig. 11: Intarsia vase, Steuben Division, Corning Glass Works, Corning, N.Y., ca. 1920–1929. Blown, with encased design. H.6.9 in. Bequest of Gladys Welles. 69.4.221. Frederick Carder (1863–1963) was trained in England and came to the United States in 1903 to set up Steuben. During his thirty years as director, Carder developed a great number of designs, shapes, and color techniques—more than any other glassmaker in the country. He considered Intarsia, which had a design encased between two layers of glass, the most difficult of the techniques he developed. |

Cut and engraved glass was also popular in the mid-nineteenth century, but the time-consuming technique involved made the results very expensive. It was made almost exclusively on the East Coast, where there was a market for more costly glassware and was initially copied from European styles, especially English and Bohemian pieces. By the 1870s, glassmakers here had developed their own style of what was termed rich cut glass (Fig. 8), employing very thick blanks and very deep cutting, the results causing the glass to sparkle in artificial light. Cutting shops opened all over the country, and for about the next twenty-five years, cut glass was one of the most popular wedding gifts.

In the 1880s, Victorian glassmakers began to produce elaborate colored and decorated pieces called art glass and intended for display in parlors. The Mt. Washington Glass Company in New Bedford, Massachusetts, was one of the principal producers of heavily advertised and brilliantly colored art glass with such exotic names as Burmese (Fig. 9) and Crown Milano. Other significant makers were Hobbs, Brockunier and Company in Wheeling, West Virginia, and the New England Glass Company, which moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to Toledo, Ohio, and became the Libbey Glass Company in 1888.

Partly as a reaction against these highly decorated wares, Louis C. Tiffany began to produce opalescent stained glass windows and then tableware, lamps, vases, and other objects (Fig. 10) in the Art Nouveau style. Colorful, but much less formulaic, Tiffany’s studio in Corona, Long Island, started a trend in decoration that remained popular until the 1920s and was adopted by other glasshouses. Steuben Glass Works in Corning, New York, was one of the most innovative of these glasshouses. It was directed by Frederick Carder, who developed many new colors, designs, and techniques (Fig. 11). In the 1920s and 1930s, hand production of everyday glassware was phased out as machines were used to make a wide range of wares.

Today, glass artists work in studios, and they produce everything from small beads to large sculptures. Practical wares, including windows, bottles, and table glasses, continue to be made in factories by machines. The American glass industry has continued to evolve with new technologies and designs.

1. All of the objects illustrated in this article are in the collection of the Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York.

The late Jane Shadel Spillman was Curator of American Glass at The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, New York and the author of numerous books and articles on glass and its use in the home.

This article was originally published in the 9th Anniversary (2009) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA was affiliated with Incollect.com.