Grandma Moses: American Modern

Few Americans needed a map to locate “Grandma Moses Country” in the 1950s. For the literal, it could be plotted as that corner of the United States where New York adjoins Massachusetts and Vermont. For most people, though, it was a landscape of the imagination—an idealized and geographically indeterminate place of hill and dale planted with tidy houses and barns and populated by hard-working yeoman families. It proved easy to find. Grandma Moses images were ubiquitous in post-World War II America, apart from her paintings, appearing in housewares, greeting cards, magazine advertisements, on television, and in the movies. Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses"(1860–1961) herself served as a national icon. Her public image as a farmer’s wife, all but cast in amber from the nineteenth century, amplified popular understanding of her work and lent authority to her vision of a rural past for an increasingly urban nation.

HOMEMADE MODERNISM

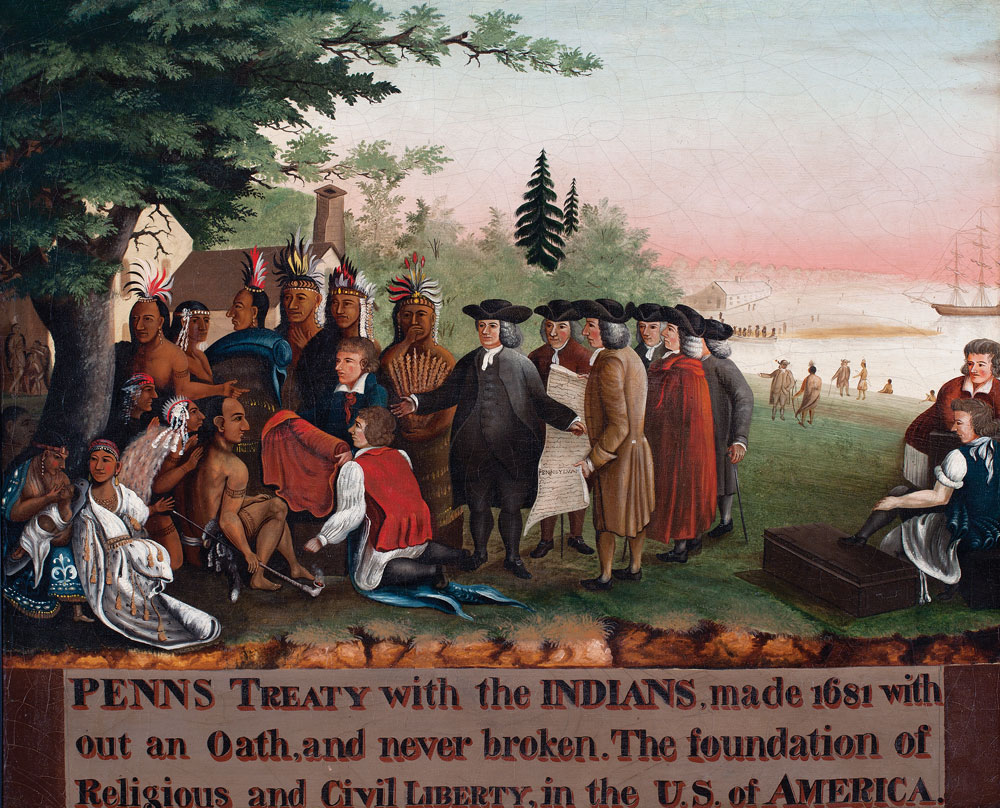

Between 1936 and 1938, the Museum of Modern Art in New York organized three exhibitions—Cubism and Abstract Art; Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism; and Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America—in a series intended “to present in an objective and historical manner the principal movements of modern art.” 1 The first two exhibitions represented undisputed leading lights of modernism, such as Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Marcel Duchamp, and Paul Klee. Masters of Popular Painting, on the other hand, featured the work of mostly little-known painters—from both Europe, such as Camille Bombois, Séraphine Louis, Henri Rousseau, and Louis Vivin, and America, including Edward Hicks (Fig. 1), John Kane, Joseph Pickett, and Horace Pippin—all of whom who had little or no formal training in the arts and created their work beyond the boundaries of the “art world” of their time and place. The three projects distill MoMA’s early exhibition programming. From its inception in 1929, MoMA had what the art historian Thomas Crow has recently called “a dual commitment” to European modernism and the art of the “common man” in America. It was from within this complex historical nexus of “folk art” and modernism that Moses was catapulted to international fame on the eve of World War II.

In 1939, the year after Masters of Popular Painting, MoMA presented two exhibitions that are revealing in their juxtaposition. From October 18 to November 18, the museum debuted three of Moses’ paintings to an art world audience in an exhibition, Contemporary Unknown American Painters, curated by the influential collector and dealer Sidney Janis. This was an exclusive “members’ only” show, then a common practice at MoMA. Overlapping slightly with this exhibition was a public one, Picasso: Forty Years of His Art, on view November 15, 1939, through January 7, 1940, the largest retrospective of Picasso’s work to date, featuring more than three hundred works. While the overlap of these two exhibitions may have been purely coincidental, the relationship between the work of Moses and Picasso, as well as other modernists, was definitely not inconsequential or superficial. Moses’ work and the debates that have surrounded it since her first outing at the Galerie St. Etienne in New York serve as a nearly perfect litmus test for understanding the complexity, politics, and contradictions of modern art in America from the late 1930s until her death in 1961.

MODERN / PRIMITIVE

In the decade after her introduction to the art world, Moses went from being an unknown farm wife in rural upstate New York, who happened to paint, to an international artist celebrity. In 1950 an exhibition of fifty of her paintings, organized by Otto Kallir, the director of the Galerie St. Etienne, under the auspices of the U.S. Information Service, made her work available for the first time to a hungry European public. The tour began in Vienna, at Kallir’s former Neue Galerie, where he had been one of the earliest champions of Austrian Expressionists such as Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and Oskar Kokoschka, before traveling to the Netherlands, Germany, and Switzerland, and finishing up in Paris, the “birthplace” of modern art, at the Musée National d’Art Moderne. While Moses had entered the art world through no less an arbiter of taste than MoMA, over the course of the 1940s, her overwhelming commercial success made her work suspect to the majority of American art critics, who by and large bemoaned the European tour of Moses’ works. By 1950 American critics had widely embraced abstract expressionism, claiming it to be the first American victory in an international war over artistic supremacy. However, in the aftermath of the horrors of World War II, which Europe experienced more directly than America, the French critics and public ate Moses’ pictures up. As one American in Paris summarized the French response to Moses’ work: “She is bound to mean the most to everyday people living in an unhappy world who, during the few minutes they look at Grandma’s pictures, drink in her memory of a happy world.” 2

MODERN HAPPINESS

In the United States, the paintings of Grandma Moses engendered a sense of community in an era marked by widespread perceptions of alienation—the very landscape of abstract expressionism. As the “American Dream” came to be defined as life in a single-family dwelling on the outskirts of an urban center, a sentimental mythology of domesticity evolved as an answer to the pervasive anxiety engendered by the demographic relocation to the suburbs. Moses, understood in her lifetime as a memory painter, an artist from an earlier era and rural place, provided an ideology of hearth and home for the new patterns of life in suburban America. Often taken in her day to be sui generis and apart from the times in which she lived, the popularity and authority of Moses’ artistic vision derived not from her singularity but rather from her role as heir to myriad traditions in American visual culture.

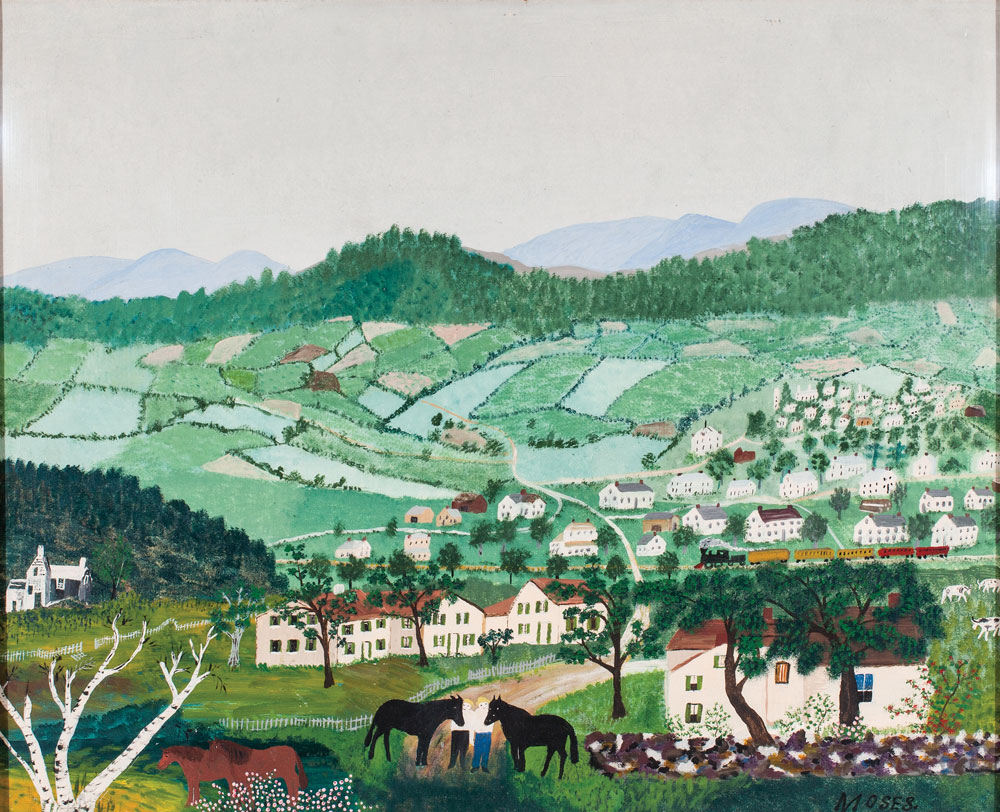

Consider the painting Cambridge (Fig. 2). Painted in 1944, during the depths of World War II, with the United States fully mobilized in Europe and Asia, Cambridge depicts a valley settlement in upstate New York, just northwest of Bennington, Vermont. Sheltered between the viewer and the distant mountains is a village rife with implication for the period as well as references to the American scene of the previous century. Moses invites the eye by creating a break in the stonewall at foreground and providing a narrative path—literally a winding road—that leads us between an evocative meeting of two black horses, their bridles held by a pair of men in straw hats. From this initial, liminal moment, Moses presents a prosperous landscape of white houses punctuated by a steam engine (yet another black horse, iron now) pulling a train, and up onto a checkerboard hillside of tidy fields. It is a scene of harmony and contentment, grounded in agriculture and architecture, with symbols of commerce readily at hand to reference larger worlds beyond the verdant mountains. It is the very ideal of small-town America that rose to prominence in the popular imagination in the 1930s and became institutionalized in the national landscape by the 1950s.

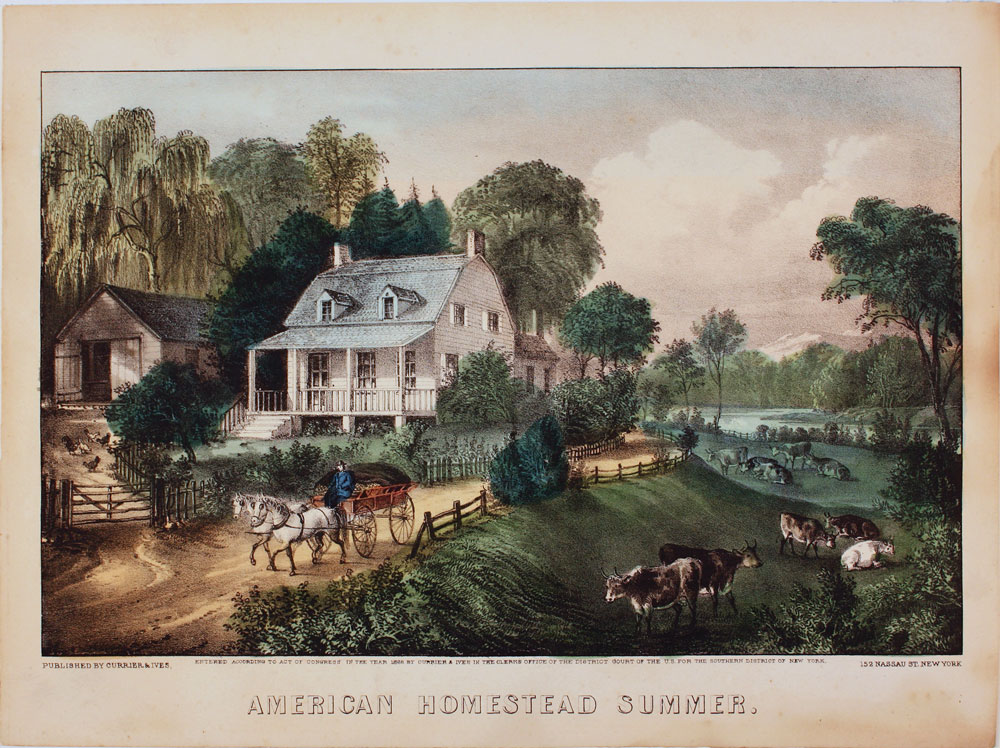

Idealization of small-town life has a long tradition in American culture. As industrialization and urbanization transformed the American economy and dramatically altered the landscape in the course of the nineteenth century, giving rise to bustling factories in busy cities, a new ideal emerged in the collective imagination—that of the yeoman family living autonomously in a house of their own. Trading in an age-old Jeffersonian concept—witness the paintings of Thomas Cole (Fig. 3) and so many of his followers in the 1830s and ’40s who saw the promise of the young nation realized in a land of cabins in the wilderness or the writings of Henry David Thoreau—the idea of the detached house in the country was inextricably linked to modernity. As city life became normative, an industry sprang up to reacquaint Americans with the virtues of country life, real or imagined. Longing for the countryside picked up steam after the Civil War, so much so that a chromolithograph of The Old Homestead by Currier & Ives became de rigueur in the new middle-class interior by the turn of the century. Fifty years later, Grandma Moses’ ability to recombine such imagery lent authority to her work, making a coda out of sentimental Victorian visual culture.

BORROWING FROM THE PAST

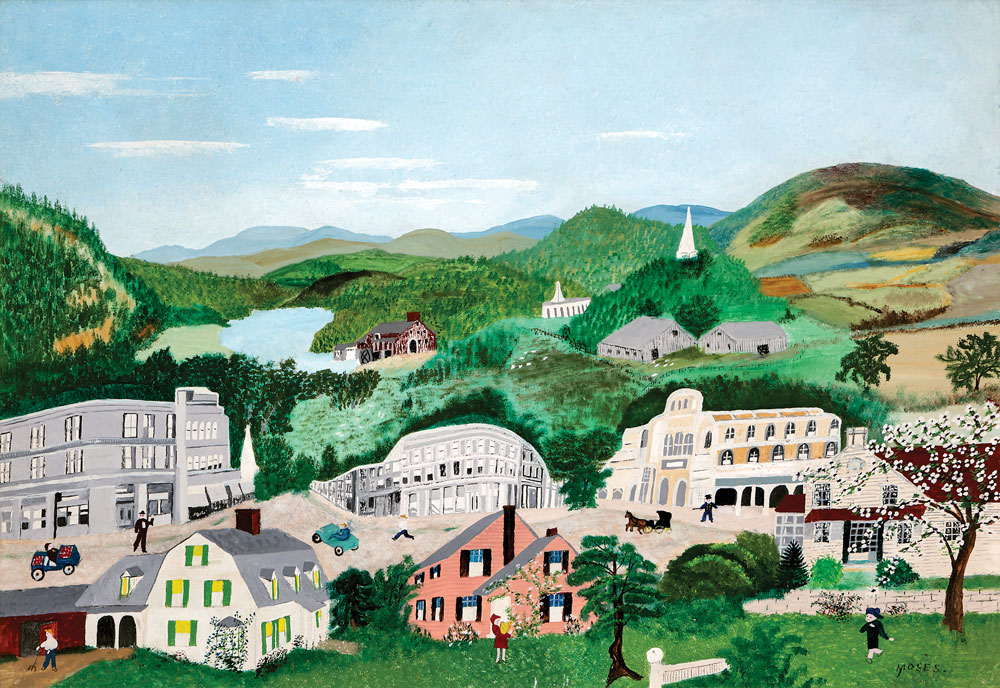

Moses was ecumenical, even omnivorous, when it came to borrowing existing imagery for her work. A postcard featuring a panoramic fish-eye photo of prominent buildings in Bennington’s commercial center (Fig. 4) serves as the compositional spine for Moses’ Bennington of 1945 (Fig. 5). Though the buildings are heavily distorted by the fish-eye effect of the photograph, difficult to identify even for longtime Bennington residents, Moses nonetheless transferred the image quite directly to her painting, even maintaining the black-and-white image’s grisaille color scheme. She seemingly improvised the rest of the scene, undoubtedly drawing heavily on other unidentified sources, making it even harder to decipher as Bennington, except for a few potentially identifiable landmark structures, such as the old stone blacksmith’s shop, the Old First Church, and the Battle Monument. While it has long been recognized that Moses drew inspiration from Currier & Ives chromolithographs and the art dealer Jane Kallir has documented her use of other popular imagery, the full extent of this practice in Moses’ work is difficult to fully grasp, as this aspect of her artistic process is nearly invisible in the finished product. However, thanks to the survival of at least two substantive caches of her “secret” source materials, now in the archives of Galerie St. Etienne in New York, we can begin to cobble together a picture, much as Moses herself did, of a sophisticated creative process. Some Moses paintings, such as The Old House at the Bend of the Road (Fig. 6) and Thanks Given Day are based directly on Currier & Ives lithographs with expected adjustments to color and the substitution or addition of a new figure or tree here or there (Fig. 7). More frequently, Moses cobbled her paintings together from many sources, rarely identifiable, into cohesive, balanced wholes. The real magic in Moses’ work is the fact that she is able to pull together such disparate images into cohesive, reassuring wholes, as though they were her own memories.

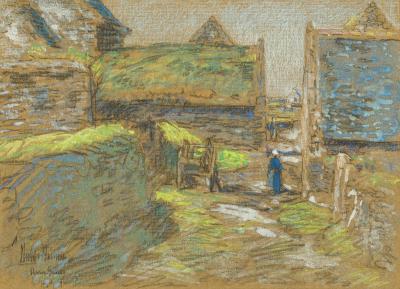

- Fig. 8: Paul Sample (American, 1896-1974), Beaver Meadow, 1939. Oil on canvas, 40 x 48-1/4 inches. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire; Gift of the artist, Class of 1920, in memory of his brother, Donald M. Sample, Class of 1921 (P.943.126.1).

Grandma Moses created visually sophisticated paintings that melded her memories of growing up in a preindustrial America with her more recent experiences in an increasingly modernized, homogenous America, saturated as it was with printed images that often drew upon nostalgic tropes of a romanticized golden age. Built on a foundation of selective memory—that of the artist’s as well as the viewers of her work—and the associative power of popular imagery, her paintings have become iconic images in America’s collective consciousness. Moses’ paintings have been providing viewers with an eternally longed for “promised land” ever since they made their way beyond the boundaries of Washington County, New York, nearly eighty years ago.

Grandma Moses: American Modern is co-organized by Shelburne Museum and the Bennington Museum with major loans from the Galerie St. Etienne. The exhibition features more than 60 paintings, works on paper, and related materials by Moses, alongside nineteenth-century masterworks as well as twentieth-century “folk” and modernist contemporaries (Fig. 8). Grandma Moses: American Modern will be on view at the Bennington Museum July 1 through November 5, 2017; it was previously on view at the Shelburne Museum from June 18 2016 through October 20, 2016. The exhibition is accompanied by a scholarly catalogue published by Skira Rizzoli Publishing. For information, visit www.benningtonmuseum.org or www.shelburnemuseum.org.

Thomas Denenberg is the director at Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vt.

Jamie Franklin is the curator of collections at the Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vt.

Click here for a related article on Folk art in Vermont.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. AFA is a division of incollect.com.

2. Karal Ann Marling, Designs on the Heart: The Homemade Art of Grandma Moses (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 225.