Investing in Antiques: Decoys

|

There are two types of decoy collectors: hunters and connoisseurs. So says Gary Guyette of Guyette and Schmidt, Inc., the country’s largest antique decoy auction firm. Until the late 1980s, with few exceptions, the profile of the decoy collector, he says, was male and if not a hunter himself, had connections with duck hunting through family or region. In the 1990s, connoisseurs of folk art began to join the ranks of collectors.

|

Third-generation hunter and collector Jeremy Kellogg lives in Clayton, New York, home of the oldest decoy show in America. This small hamlet is situated on the St. Lawrence River bordering New York and across from Canada, and is a mecca for hunters and outdoorsmen. “Hunting gets in your blood,” he says. “The ritual of getting up and out at four a.m. in sub-freezing weather—looking out over your spread [the area in which up to 200 decoys are spread out as a lure]—there is nothing like it.” For Kellogg and hunters like him, collecting decoys is an extension of their passion for hunting. Their collections represent memories of a beloved sport.

Susan and Jerry Lauren, by contrast, are not hunters; they are connoisseurs of folk art, a class in which they count decoys. “I collect the best representation of any one category which stirs my emotions,” says Jerry. “When we purchase an object we purchase not for investment, but for its purity and unique artistic merits.”

|

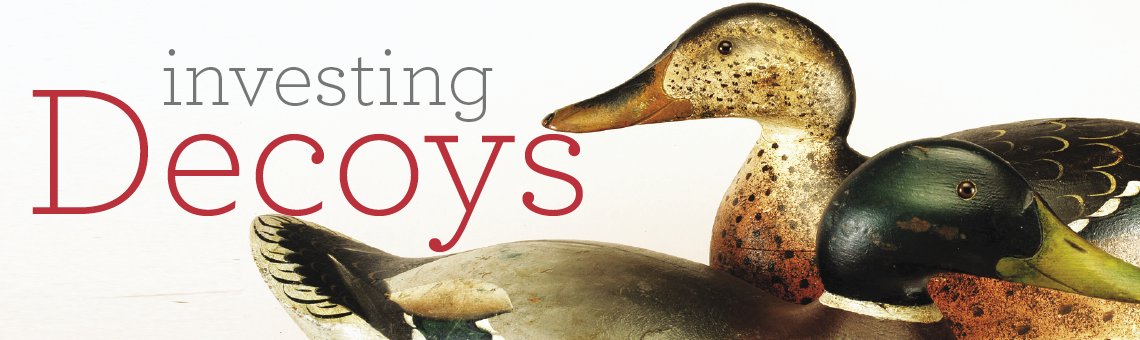

Fig. 1: Lothrop Holmes (1824–1899), Merganser drake decoy, circa 1875. Collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren; Photograph courtesy of Fred Giampietro. |

|

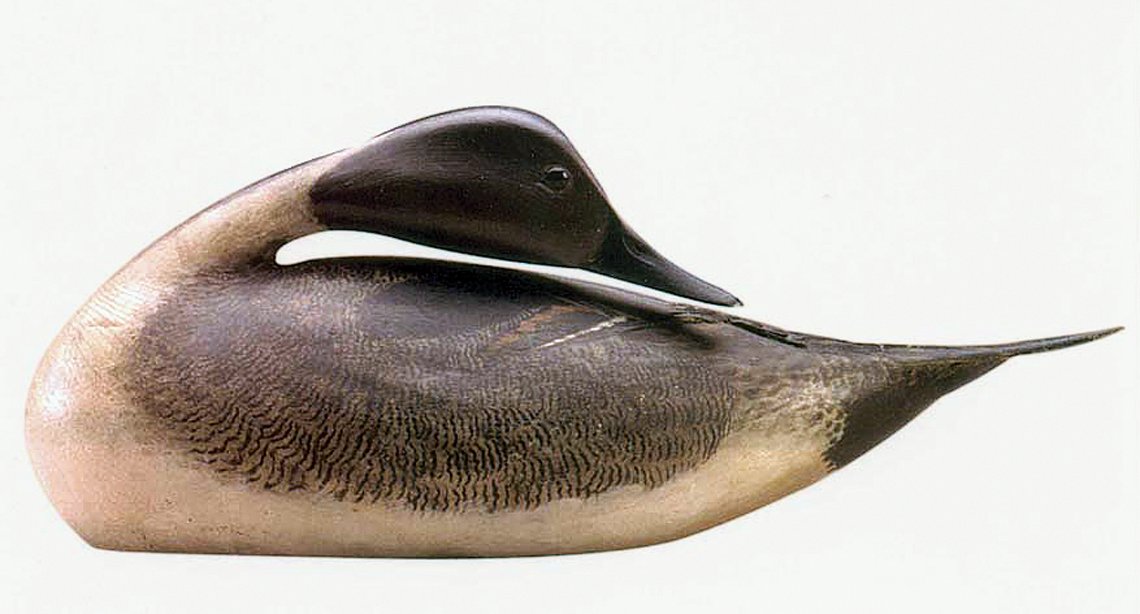

Fig. 2: Lothrop Holmes (1824–1899), Merganser hen decoy, circa 1875. Private collection; Photograph courtesy of Guyette and Schmidt. |

The Laurens acquired a decoy meeting that criteria at last year’s Winter Antiques Show (Fig. 1). Folk art dealer Fred Giampietro of New Haven, Connecticut, who sold them the decoy, describes this Lothrop Holmes merganser drake as, “One of the greatest masterpieces of American folk art. The fact that this piece is a decoy is beside the point.” He adds, “There was a lot of pre-opening excitement on this piece and Susan and Jerry were the first to make it to my booth. Within minutes the savvy pair purchased the Lothrop Holmes for $550,000.” In January earlier this year, Christie’s, in association with Guyette and Schmidt, set a new world record with the sale of a Lothrop Holmes merganser hen for $856,000 (Fig. 2).

Most decoys are not signed or dated. The only markings were usually added by hunters for identification purposes. According to Stephen O’Brien, a leading private broker of antique decoys, “Finding decoys made prior to the civil war is extremely difficult. A few areas like Nantucket, Long Island, and parts of New Jersey can date makers as early as 1840, but certainly the heyday of decoys carvers was from 1880 to 1930.” It was the insatiable demand of the markets that decimated certain species of waterfowl; some to the brink of extinction. As a result, in 1918 The Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed rendering the sale of any hunted birds illegal. In 1930 spring hunting was banned making autumn and winter the only seasons for hunting. These restrictions began the decline of carved wooden decoys for market hunters, but decoys continued to be made for sporting hunters. Carvers continued making decoys up until the 1960s when plastic decoys became more prevalent. Commercial hunting of wild fowl today is illegal and ducks served at restaurants are farm raised.

“In the early days collectors were for the most part isolated,” says Guyette. “Scattered throughout the country, no one really knew of the others.” That changed in 1963 when early collector Hal Sorenson established his magazine, Decoy Collectors Guide, which helped unify collectors. They began congregating once a year at Richard Bourne’s summer decoy auction held in Hyannis, Massachusetts. The auctions became social events with collectors bringing their families and staying at the Craigville Motel. “In the evenings, while the kids swam in the pool, the collectors would barbecue, barter, and trade,” adds Guyette. These auctions introduced new collectors to the market throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. O’Brien adds that another early influence was Adele Earnest and her ground breaking book The Art of the Decoy: American Bird Decoys (1965), the same year that William J. Mackey, Jr. published American Bird Decoys. These two books are considered the early bibles for decoy collectors. O’Brien notes, “Adele certainly had ‘an eye,’ and was largely responsible for bringing decoys into the mainstream of American folk art.”

|

Fig. 3: William Bowman Curlew, Long Island, New York. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Guyette and Schmidt. |

|

Fig. 4: Elmer Crowell (1862–1952), Preening pintail drake. Private Collection; photography courtesy of Guyette and Schmidt. |

The $10,000 mark was broken at a the Bourne auction in 1973 of William J. Mackey, Jr.’s decoy collection. Hunter-collector James McCleery purchased a William Bowman Curlew from Long Island, New York, for $10,500 (Fig. 3), setting a new record for any decoy. Up until then most collections represented a particular region or breed, but Dr. McCleery collected the best from all categories. His collecting style helped make decoys a recognized art form. In 2000, when Guyette and Schmidt, in association with Sotheby’s, sold Jim McCleery’s collection, the Bowman curlew sold for $464,500, making the compounded annual rate of return 15.07 percent.

1986 was the year sales figures for decoys broke all records, attracting media attention in the process, according to decoy expert and dealer Russ Goldberger of RJG Antiques in Rye, New Hampshire. That year Richard Bourne sold a wood duck by Joseph Lincoln for $205,000 and a new record was set at a Richard Oliver auction with the sale of an Elmer Crowell preening pintail drake for $319,000 (Fig.4). That record stood until 1997, when Christie’s sold a running curlew by an unknown maker for $395,000. The same Elmer Crowell preening pintail that broke a record in 1986, sold again at Christie’s for $801,000 in 2003, the year Christie’s showcased decoys during Americana week, thereby formally integrating them with Americana. The records keep climbing. This September, the same Crowell pintail drake entered the scene once again, becoming the first million dollar duck decoy ever sold, brokered by dealer Stephen O’Brien and bringing $1.13 million (see Noteworthy Sale, below; Fig. 4); concurrently, O’Brien sold a Crowell sleeping goose for the same record price (Fig.5). Of the landmark sales the Boston dealer said, “I have always loved A. E. Crowell’s work, he combined elaborate and precise carving details in his earliest decoys, coupled with unsurpassed paint patterns; his very best painted sculpture captures the essence of each species.”

|

Fig. 5: A. E. Crowell (1862–1952), Sleeping Canada goose, circa 1917. Courtesy of Stephen O’Brien Fine Arts. O’Brien sold this decoy in a private treaty sale this September for $1.13 million. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 2000 for a record $684,500; previously it sold at Skinner in 1981 for $48,000. The compounded annual rate of return to date is 12.41%. |

|

Mason Premier Mallard drake and hen decoy pair, circa 1910. Courtesy of Russ and Karen Goldberger, RJG Antiques. Many fine decoys are available at prices other than those that set records. This pair is valued at under $30,000. |

Experts agree that the two master carvers were Lothrop Holmes (1824–1899), the Kingston, Massachusetts, craftsman who carved only for his own use, and A. Elmer Crowell (1862–1952), of East Harwich, Massachusetts, who began carving full-time as a business in 1912. Of the pair whose work holds down most of the top price records, Crowell was the more prolific. When asked about the criteria used to determine a masterpiece, Goldberger cited condition, overall form, rarity of species, and, ideally, unusual poses such as sleeping or feeding. All those interviewed for this article agreed that there is room for growth in the field of decoy collecting. Buying the best you can afford, they say, over time, will bring the best return on your investment.

|

|

Noteworthy Sale

Stephen O’Brien, Jr. Fine Arts

Preening Pintail Drake Decoy

Carved and painted wood, ca. 1915

A. Elmer Crowell (1862–1952), East Harwich, Ma

Sold for a record-setting $1.13 million

Courtesy Stephen O’Brien, Jr. Fine Arts, Boston, Ma

Sales History:

– Sold in 1986 at Richard Oliver auction, ME, for $319,000

– Sold in 2003 at Christie’s, NY, for $801,500

– Sold in 2007 in private treaty sale through Stephen O’Brien, Jr., for $1.13 million

“Dealers and collectors have been guessing which decoy would be the first to reach the million dollar mark,” says decoy broker Stephen O’Brien, Jr. With his sale of this drake, and a concurrent sale of a Canada goose, also brokered by O’Brien, the answer lies with both birds—each sold for $1.13 million.

When sold at Christie’s in 2003, deputy chairman John Hays called the decoy “the most important bird in America…by the best maker.” Similar praise was echoed by Decoy Magazine editor Joe Engers, “Without a doubt, the [Crowell] pintail drake is the most familiar decoy in the world.”

Commenting on the burgeoning decoy market, O’Brien said, “Waterfowl decoys are a uniquely American art form that have moved to the forefront of the folk art market. Both buyers and sellers have recognized their potential and prices are beginning to climb. The Crowell pintail drake is one of the most iconic and famous decoys of all.”

Nancy N. Johnston is a private consultant and broker for antiques and art, and a regular contributor to Antiques & Fine Art Magazine.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|