Japanese Art 1910–1940 Japan’s Traditional and Modern Worlds Collide at Thomsen Gallery

|

Yamamoto Chikuryōsai II (ac. ca 1929–55), Handled Serving Basket, ca 1920. Bamboo and rattan. |

|

Japan’s Traditional and Modern Worlds Collide at Thomsen Gallery

By Benjamin Genocchio

Japanese Art 1910–1940

Thomsen Gallery

March 16 - June 2, 2023

9 East 63rd Street

New York, NY 10065

Thomsen Gallery, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York, is well-known for its exceptional selection of fine Japanese paintings and other works of art including ceramics, bamboo baskets and lacquer. Thomsen tends to have objects from the past, occasionally drifting forward to the present but focused for the most part on exquisite examples of Japanese artistry through the centuries.

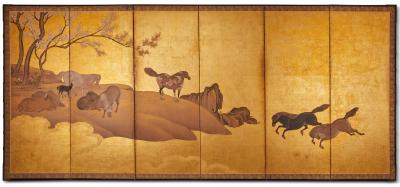

A current exhibition, on view through June 2, happily provides ample evidence of his aesthetic preference with an exquisite collection of folding screens and hanging scrolls from the Taisho era (1912–26) and early Showa era (1926–89), as well as bamboo baskets and gold lacquer boxes, also from the Taisho and Showa eras. The objects cross freely between decorative genres of art and design.

|

Kono Yoshimine (ac. Showa era), Young Girl with Autumn Plants, 1930s. Signed Yoshimine saku (made by Yoshimine) and sealed Yoshimine. Six-panel folding screen; ink and mineral colors on paper with silver leaf. |

|

Clockwise from left: Iizuka Rōkansai (1890-1958), “Moon Rabbit” Flower Basket, mid-1930s; Iketani Hiroko (Woman painter ac. Taisho-early Showa eras, early 20th century, Hydrangea in Rain, 1920s–30s; Set of Writing Box and Document Box with Poem Cards, ca. 1920. Maki-e gold lacquer on wood; Kōda Katei (1886-1961), Document Box with Poem and Bush Clover, 1930s. Maki-e gold lacquer on wood with metal and shell inlays. |

| |

Yamaguchi Sōhei (1882-1961), Spring Evening, mid-1920s. Hanging scroll; ink, color, shell powder and gold on silk, in silk mounting. |

Historical artworks executed in traditional formats and materials often emphasize technical perfection, and Japanese culture excelled like no other in this regard. This is undoubtedly the case for the domestic objects included in the show, the intricate gold lacquer boxes in particular, such as a set of writing boxes and document boxes with poem cards, from circa 1920, made of maki-e gold lacquer on wood.

This same quality is visible in several important screen and scroll paintings on display which have a secondary, perhaps more important story to tell. Thomsen wanted to highlight this period in Japanese art and culture for reasons he explains in a text accompanying the exhibition. “The Taisho era, and early Showa era, specifically the modern pre-war era of 1910–1940, was a time of great change for Japan and its arts,” he writes. “Superb works were created for the domestic market, in contrast to the export-oriented output during the Meiji era (1868–1912).”

Changes were apparent in the paintings during this period. Though Taisho and early Showa era paintings were still painted using the traditional media of ink and mineral pigments and mounted as folding screens or hanging scrolls, Thomsen points to the evidence of experimentation with new themes and perspectives. “They shifted from stylized depictions of nature to naturalistic botanical studies. Making trips abroad, many painters incorporated foreign elements from their travels into their work.”

Probably the most important work in the exhibition is a pair of folding screens exhibited at the 6th Bunten National Art Exhibition in Tokyo in 1912. They are by Gōda Ippō (born circa 1875, death date unknown), titled “Itabeigiwa” which translates as “By the Fence”, from 1912, in ink and mineral colors on silk. Here the artist closely, precisely depicts a garden fence with birds and plants, recording elements of the wood and natural decay.

|

Hasegawa Chikuyū (1885-1962), Deep in the Woods, 1930s. Pair of two-panel folding screens; mineral colors on paper. |

| |

Okajima Tesshū (b. 1890), Hydrangea and Turkeys, 1920s. Oversized two-panel folding screen; ink, mineral colors, gofun, and gold wash on paper. |

“While the fence provides overall structure,” Thomsen says, “the chief subject, given pride of place on the right-hand screen, is a young shrub of Paulownia, a plant more often seen in earlier Japanese art in stylized form as part of a crest used by several leading families as well as the imperial house. Here, by contrast, it is shown as it appears in real life, having already flowered, its larger leaves now beginning to decay, while tiger lily and a cereal crop, perhaps maize, flourish to either side.”

The surface of every leaf is very carefully and naturalistically painted — a marvelous technical achievement in and of itself. The close-up nature of the composition is quite striking, with much of the painting dedicated to the ultra-realistic, minute depiction of a panoramic fence that limits the viewer’s field of vision and forces us to focus on a narrow, shallow space. This foreshortening of perspective points to an artistic awareness of new, modern European avant-garde painting styles.

There is so much to contemplate in this very large painting, each screen is 61½ x 69 inches, together filling an entire wall area. To maintain a seamless visual continuity across so large a space represents an astonishing technical achievement and places this painting among the best examples of the artist’s work available on the open market.

It is also worth drawing some attention to a painting by Kono Yoshimine, “Young Girl with Autumn Plants,” from the 1930s, a six-panel folding screen made of ink and mineral colors on paper with silver leaf. The depiction of a young girl was unusual in pre-modern Japanese art, Thomsen says, which again locates this work, culturally, as a more formally ambitious composition produced for a domestic Japanese market.

|