Louis Kahn: Building in Light

How does one mount an exhibition dedicated to architecture? Are not buildings meant to be occupied, inhabited, lived in?

This month, the Kimbell Art Museum, in Fort Worth, Texas, will attempt to answer this question by staging a show dedicated to the work of Louis Kahn (1901–1974), widely considered one of the most influential American architects of the twentieth century. “Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture,” which runs from March 26 to June 25, brings together an assortment of drawing, photographs, architectural models and films. Taken together, these materials are testimony to the unorthodox style of the Estonian-born architect, who resisted the principles of modernism espoused by Mies van der Rohe and other adherents of the International Style. Instead, Kahn attended to the spiritual qualities of a building—“what the building wants to be”—by bringing structural elements into view. This was controversial at times, as when he designed a ceiling of exposed concrete in a tetrahedronal pattern for the Yale Art Gallery, which opened in 1953.

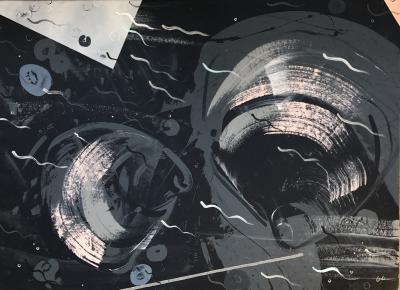

This landmark exhibition, which was previously at the San Diego Museum of Art, will be accompanied by a selection of pastels made by the architect during a three-month period in 1950-1951 when he resided at the American Academy in Rome. These works manifest a concern with the fusion of architecture and light, the way that ancient sites in Italy, Greece and Egypt are illuminated at various times of the day. This, in turn, informed the architect’s design for the Kimbell Art Museum, a cross-shaped configuration of lead-roofed, post-stressed concrete vaults with “narrow slits to the sky” to admit natural light. Once again, Kahn defied the prevailing wisdom of the day, which held that artificial light was best suited to the gallery space. When asked about his design philosophy, the rumpled builder—known for his bow ties and a shock of white hair—often resorted to cryptic pronouncements like, “The creation of art is not the fulfillment of a need but the creation of a need,” or, “The sun never knew how great it was till it hit the side of a building.

The exhibition at the Kimbell Art Museum, which was organized by Vitra Design Museum, in Weil am Rhein, Germany, is arranged in six thematic categories: “City,” on the architect’s relationship to his adopted hometown of Philadelphia; “Science,” on his curiosity in the structural laws of the natural world; “Landscape,” on the dialogue between building and place; “House,” on the home as a starting point for understanding architecture in general; “Eternal Present,” on his engagement with classical architecture, beginning with his three-month stay at the American Academy in Rome; and, finally, “Community,” on the social significance of his buildings.

In the final analysis, the builder invented his own language, one that transcended the classical vocabulary of the Beaux Arts tradition and the rectilinear simplicity of modernism. Kahn was not wedded to any one architectural style, but devised each building to suit a particular place and purpose. Nowhere is this more evident than with his design for the Kimbell Art Museum, which opened in 1972. As then-director Richard Brown remarked at the time, it was “what every museum has been looking for ever since museums came into existence.”