Major Survey of Work of Richard Hambleton Takes us Beyond the Shadowman

_0.jpg) |

Richard Hambleton, Untitled (Jumping Shadow Diptych), 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 96 inches. |

A Major Survey of the Work of

Richard Hambleton Takes us Beyond the Shadowman

by Benjamin Genocchio

Conventional wisdom holds that the street artist Richard Hambleton lived his life in the shadows of the art world, for the most part living and working unrecognized and unknown. That is not the full story, far from it, as a visually diverse, expansive and impressive retrospective exhibition at Chase Contemporary in Soho seeks to show.

The first misnomer surrounding Hambleton is that he was a street artist. He worked in public, initially, in his native Canada and then when he moved to New York full time in the late 1970s creating photographs of himself and famously chalk outlines of bodies on the pavement to simulate actual police crime scenes. 620 of them were executed between 1976 and 1979 in San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, Victoria, Vancouver, Banff, Regina, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Chicago and New York.

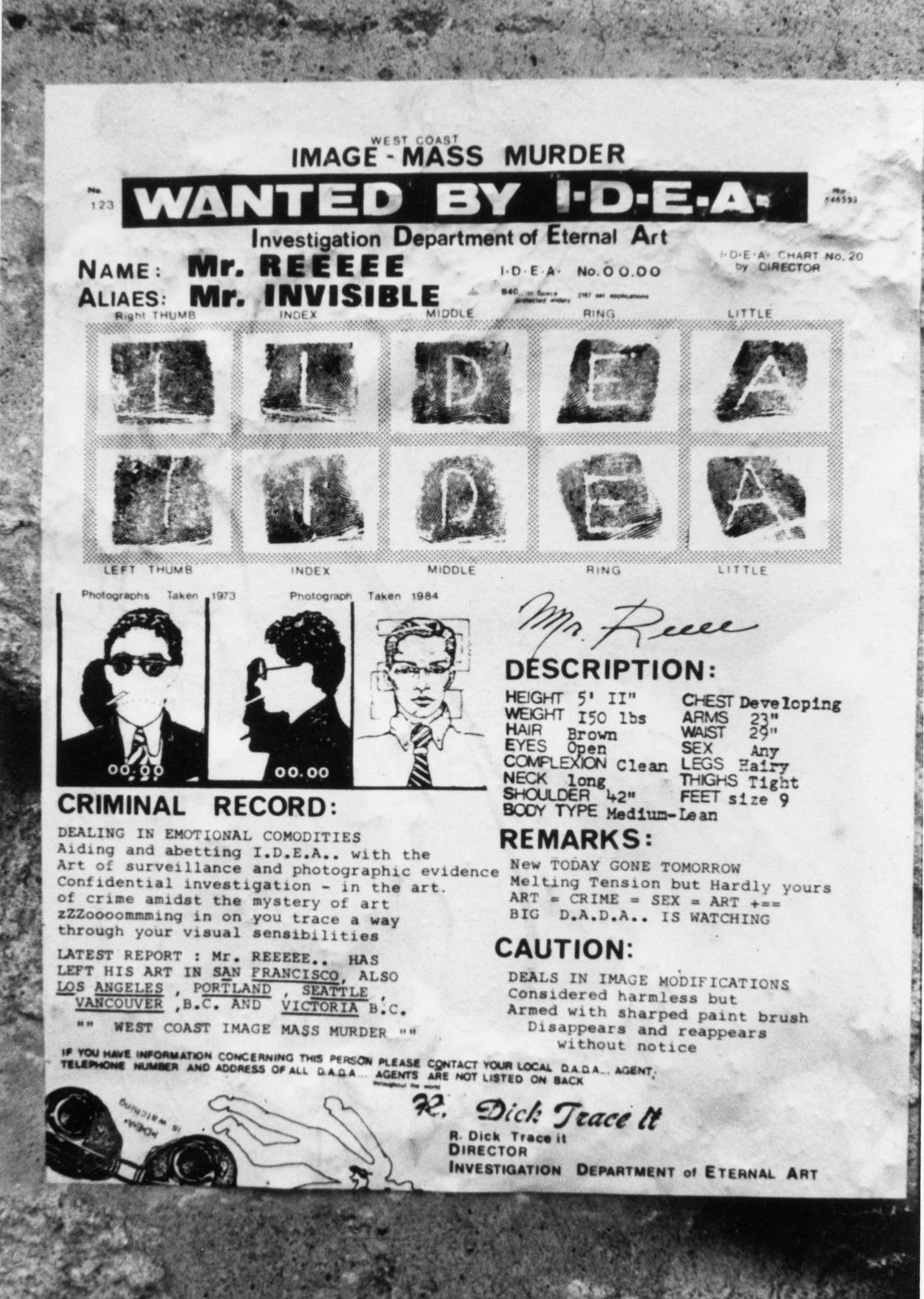

| .jpg) | |

| Left: Richard Hambleton, Image Mass Murder, c. 1976-1979. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 5 inches. Right: Richard Hambleton, Image Mass Murder, c. 1976-1979. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 5 inches. | ||

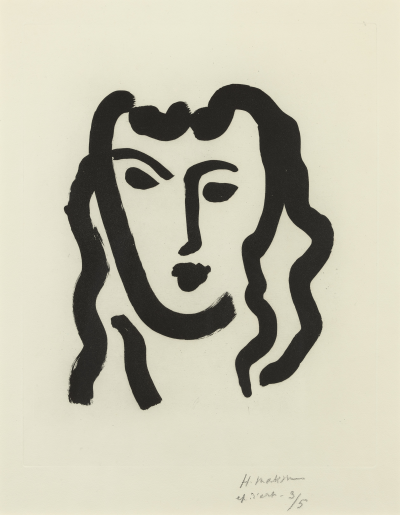

Works from the Image Mass Murder series are on show here for the first time and provide a timely reminder of Hambleton’s origins as a conceptual artist with a strong social conscience — the series, made under the pseudonym Mr. Ree, reflects on gun violence, in particular spiraling murder rates across the United States and Canada. They also introduce the silhouette as a thematic trope, which the artist was quick to transition into his Shadowman paintings and for which, today, he is justly famous.

Hambleton liked to work at night, roaming the streets from dusk until dawn looking for material for his photographs and later, beginning in the early 1980s, public paintings of shadow figures on the Lower East Side and in Soho. These early shadow figures are part of the Nightlife series and garnered the artist great recognition, even fame. Between 1981 and 1984 he participated in more than 40 group exhibitions worldwide according to an excellent scholarly catalog produced for the show, including, in 1984, the prestigious Venice Biennale. The shadowman had come out of the shadows.

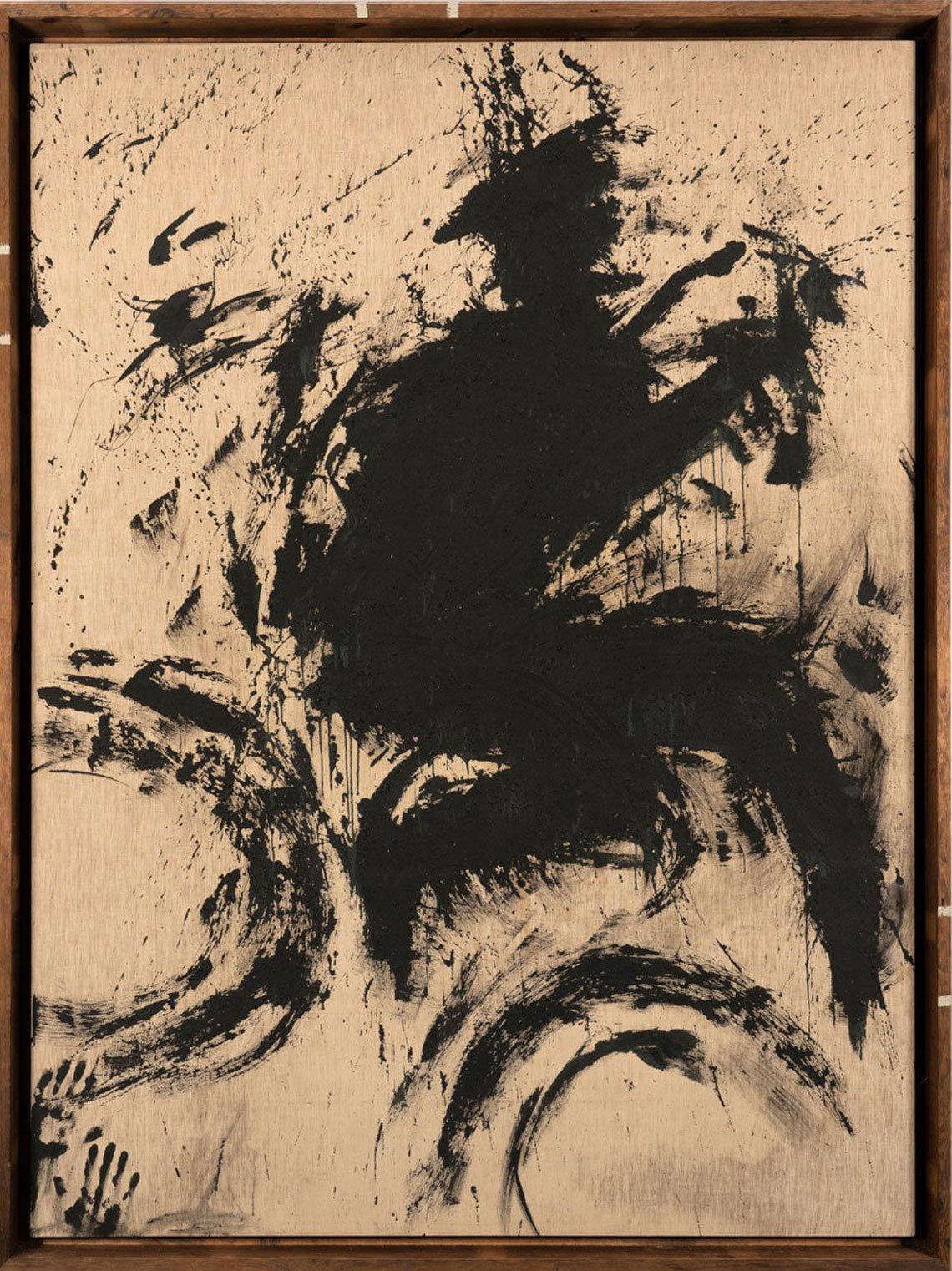

The initial shadowman figures were black, clandestine and strange — even menacing in appearance. There was always something raw, gestural, energetic, performative about them, beginning with the act of them being done at night. But it is also visible in the expressive brushwork. Performance painting is one way to describe his output in the studio, which encompassed painting shadow figures on everything from found or appropriated objects, from doors and street signs to magazine covers, paper, and eventually stretched canvas on a monumental scale to simulate a wall or pavement.

|  | |

| Left: Richard Hambleton, Wanted by I.D.E.A. (Image Mass Murder), c. 1976-1979. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 5 inches. Right: Richard Hambleton, Mr. Reeee (Image Mass Murder), c. 1976-1979. Gelatin silver print, 7 x 5 inches. | ||

| |

| Richard Hambleton, Shadow Rider, circa 1985. Acrylic and sand on linen, 87 x 64.5 inches. |

Examples of early shadow man paintings on diverse supports are included in the exhibition including Shadow Rider, circa 1985, a shadow self-portrait of the artist riding a bicycle made of black acrylic paint mixed with sand on linen. It’s a stunning painting, the first work you see when you enter the exhibition, and points not only to the autobiographical nature of much of Hambelton’s artwork but to the way in which he sought to invoke emotions, feelings and experiences, in this case riding a bike.

The performative dimension to Hambleton’s paintings is again visible in subsequent shadowmen works, including Untitled (Jumping Shadow Diptych), 1997, a fun and dynamic painting of a crouching, dancing shadow figure in silver paint on black that is really one of the best paintings I have seen in a long time, and also Dancing Shadow Triptych, again from 1997, in which we see the artist seemingly making a formal and thematic reference to the work of Henri Matisse, in particular Dance, 1910.

.png) |

| Richard Hambleton, Dancing Shadow Triptych, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 68 x 108 inches. |

|

Richard Hambleton, Mutiny, 1985. Acrylic on canvas, 82 x 266 inches. |

References to art history abound in Hambletons’ paintings, not just to Matisse but to Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, and in particular Barnett Newman, whose signature formal vertical block of color, known as the “zip” mark, can be found in quite a few of his paintings in the current show, including the monumental seascape Mutiny from 1985, a 22 foot long seascapes showing crashing waves that celebrates the power of nature. It is part of a series of moody sublime landscape paintings from the 1980s that Isabel Sullivan, writing in the exhibition catalog, links to romanticism.

Kicking Shadow Man, from 1997, is another amazing, massive painting that holds a single wall in the gallery and that is destined no doubt to someday decorate the home of an astute collector — it’s so energetic and lively, with a figure flying through space. Critics have also pointed to the artist’s admiration for Barbara Kruger, who used the framing device of blocks of rectangular color as photographic borders for her imagery and which from time to time, as here, can also be seen in Hambleton’s paintings.

|

| Richard Hambleton, Kicking Shadow Man, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 48.43 x 211.81 inches. |

.jpg) |

Richard Hambleton, Wind Shadow, 2001. Acrylic on canvas, 51 x 79.5 inches. |

The performative aspect of the work continues pretty much throughout Hambleton’s career, evident in a late piece like Wind Shadow, 2001, in which the shadowy man figure looks like he is spinning inside a clothes dryer trying to get out. But there are also more subtle and subdued shadow man portraits, like Standing Shadowman, from 1999, or Untitled Standing Shadow, from 2017, in which the figure, with an exploding head, resembles Jean-Michel Basquiat’s self-portraits and has drawn a comparison between the two artists both in terms of their humble street and graffiti art origins and use of dark, phantom-like imagery that many critics associate with psychological pain. Some of this is certainly true, both were artists who lived troubled lives.

| .jpg) | |

| Left: Richard Hambleton, Standing Shadowman, 1999. Acrylic on found door, 80 x 30 inches. Right: Richard Hambleton, Untitled Standing Shadow, 2017. Acrylic on canvas, 80 x 30 inches. | ||

For Hambleton, much as for Basquiat, New York’s vibrant nightlife was a constant source of fascination and entertainment and both of them experimented with drugs, often to their detriment. Basquiat died at 27, of an overdose, Hambleton at 65 in late 2017, though by then his work had become increasingly defined, rarefied stylistically. Nonetheless, his drive to create, his early, performative paint handling along with the signature raw, gestural energy of his paintings never really dimmed.

|

Richard Hambleton: Beyond the Shadowman

Chase Contemporary, 413-415 West Broadway, New York

Through May 29, chasecontemporary.com

|

Richard Hambleton, Stop Sign, 2017. Acrylic on aluminum, 24 x 24 inches. |