Mary Way and Betsy Way Champlain: Evaluating the Shared Artistry

Mary Way and Betsy Way Champlain

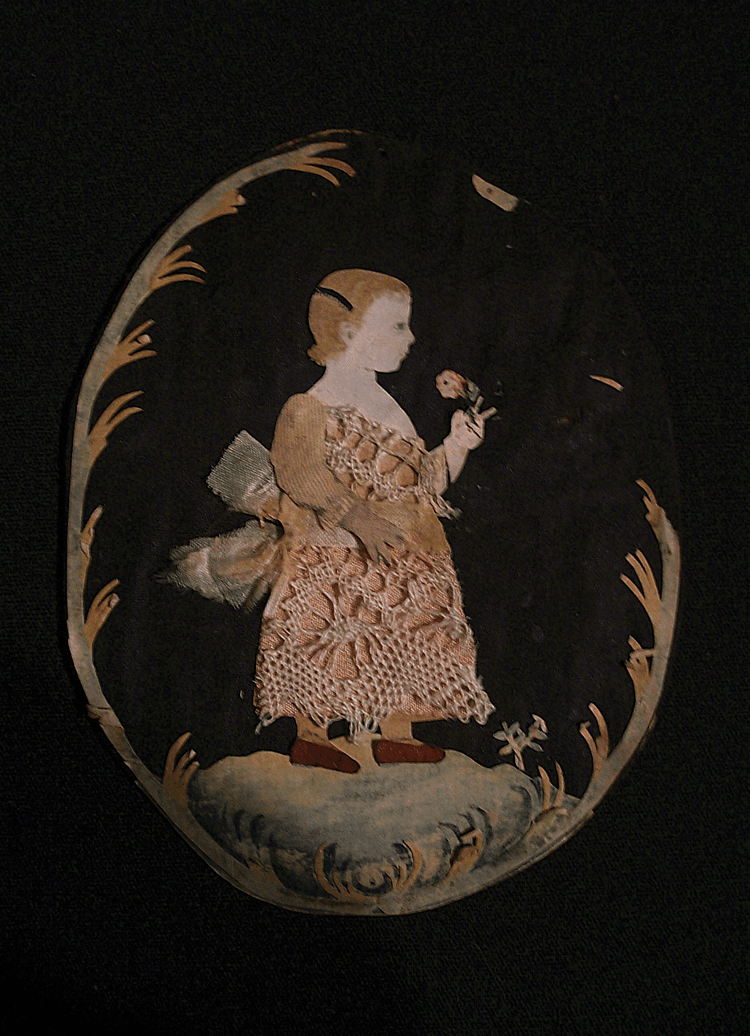

The Connecticut artist Mary Way (1769–1833) was largely forgotten until 1992 when her unique American “dressed” portrait miniatures were featured in a magazine article, where its author William L. Warren described them as: “cutout paper profiles attached to fabric backgrounds, with facial features carefully rendered in water color and with pieces of fabric pasted on the background to represent clothing.” 1 To date, American “dressed” miniatures have been associated with the hand of Mary Way.2 However, it turns out that her similarly gifted, but far less documented, sister Betsy Way Champlain (1771–1825), was in all likelihood equally involved in developing this distinctive style of decorated miniature.

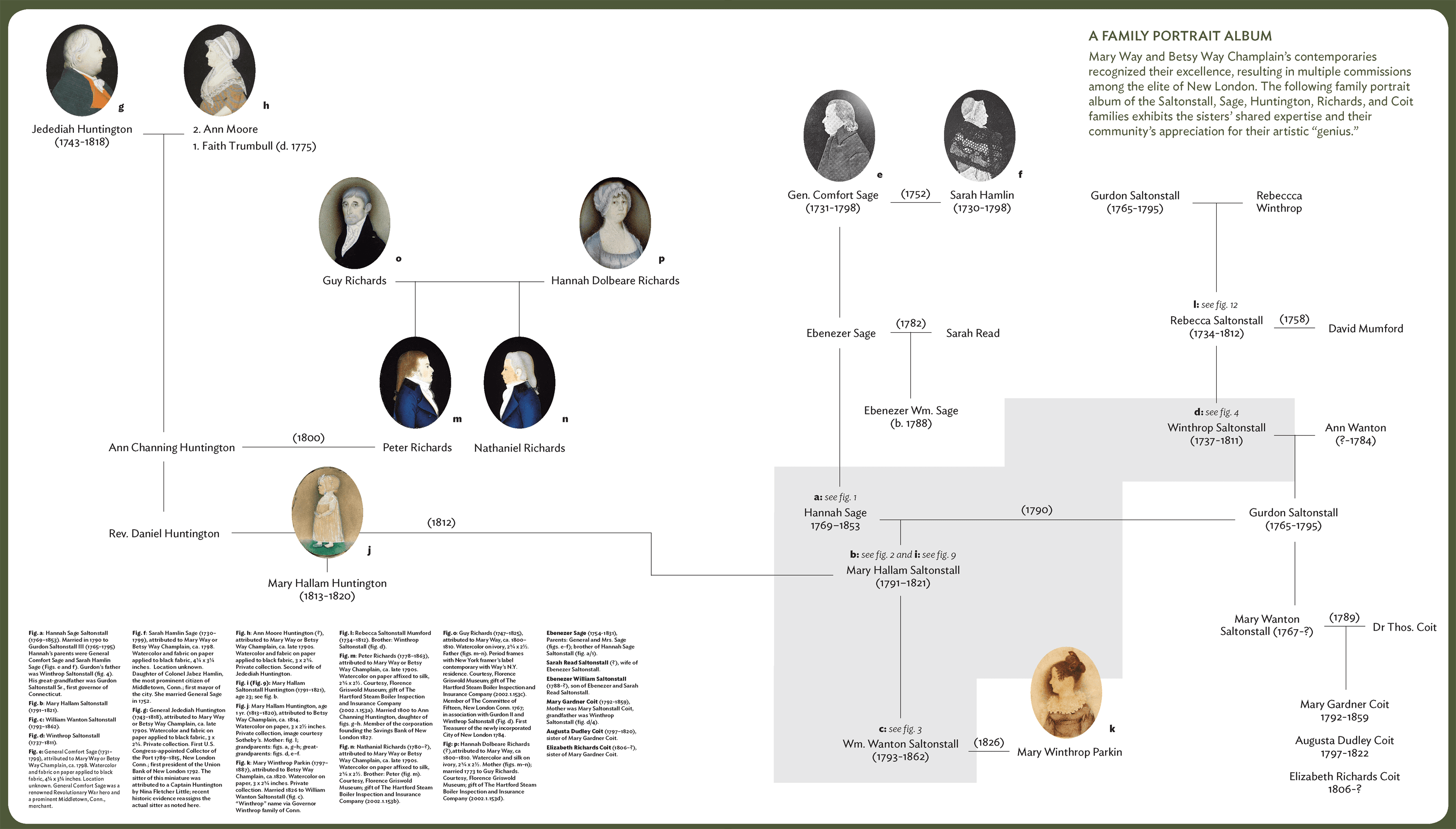

The sisters, working in New London, Connecticut, from the 1790s to the early 1800s, created an extensive body of work consisting of “dressed” portraits, as well as more traditional portraits painted on paper or ivory. Many commissions arose from within interconnected and extended members of the elite of New London County society. Although information about the sisters’ formative years continues to be elusive, newly discovered data in conjunction with information provided in available Way Family correspondence3 allows for an evaluation of Way and Champlain’s work, apparent shared stylistic development, and roots for their potential training.

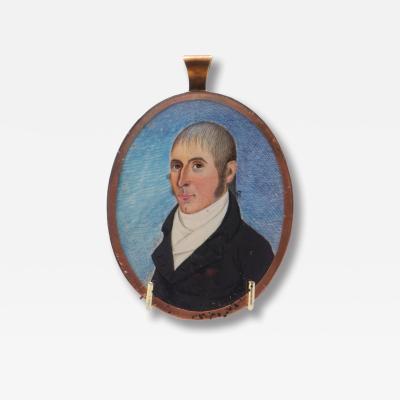

At the centerpiece of this study is a family grouping of four previously unknown dressed miniature portraits, recently discovered at auction. The group consists of Hannah Sage Saltonstall, her children Mary Hallam and William Wanton Saltonstall, and her father-in-law, Winthrop Saltonstall (Figs. 1–4). Research into these portraits has led to two paths of discovery. The first was prompted by evidence arising from evaluation of the miniature of Hannah Sage Saltonstall, which reveals a definite association with Betsy Way Champlain through her husband George Champlain, strongly suggesting a sisterly collaboration. A second path, based on a genealogical study of the core group of four miniatures, has revealed a direct kinship between four generations of five prominent Eastern Connecticut families, unrelated to Way and Champlain, who sat for the sisters. These sixteen known images (of twenty-two recorded genealogically connected family portraits4 ), all attributed to Way and Champlain, confirm the mastery of these two artists.

“A FIRST-RATE GENIUS" AND "THE PAINTER GENERAL”

Mary Way, after living within a close family network and presumably sharing the artistic spotlight with sister Betsy, left New London for New York City in 1811 at age forty-two, unmarried and hoping to refine her artistic technique and promote her professional status. Her reputation developed over the next nine years, during which time she was under the artistic guidance of several professional artists, including Henry Williams and John Wesley Jarvis, and exhibited at the American Academy of the Fine Arts.5 Mary made her own assessment of her talents in a letter to her sister early in her New York City experience: “…this was in some measure owing to vanity, or that self-conceit you know is a family disorder, as well as my ignorance of the art…I have seen but few equal, and none superior to my own—concluding therefore I had nearly arrived at perfection, [I] very modestly set myself down as a first rate genius.” Alas, Mary was forced to return to New London when progressive blindness due to glaucoma necessitated her return in 1820 to be cared for by her family. Betsy, meanwhile, had remained in New London, where she raised her family and continued to paint miniature portraits until her death in 1825. In the same letter, Mary also confirms the significant artistic success of her younger sister: “There [in New London] you are the Painter General.”

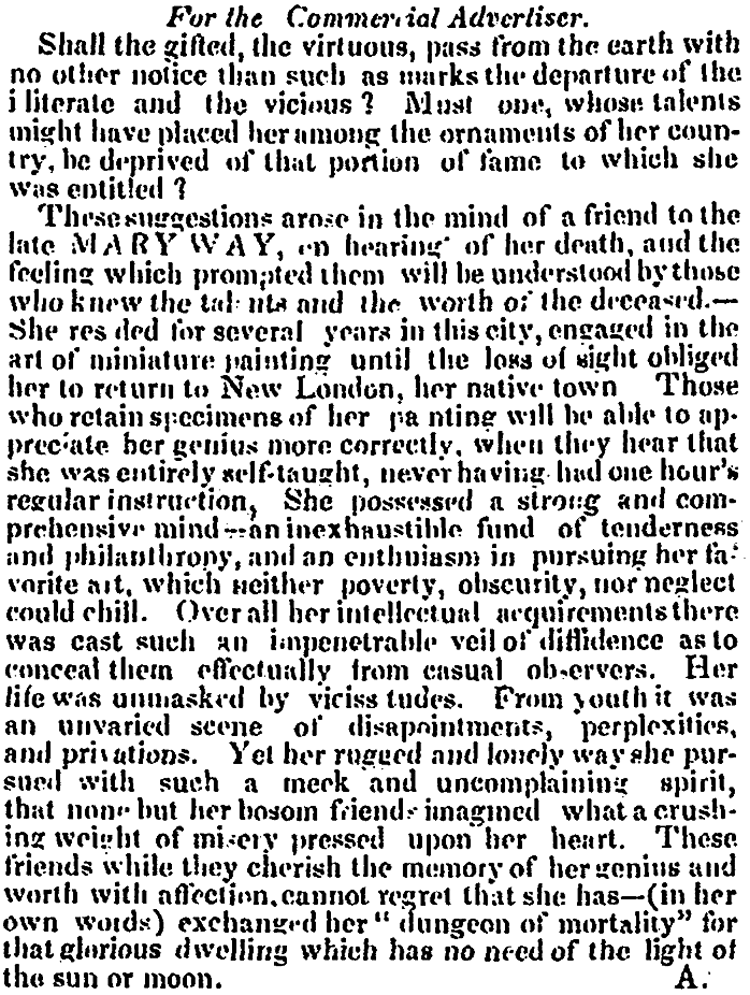

There is no documented information as to Mary or Betsy’s early training while in Connecticut. The only period reference to date is in an 1833 obituary for Mary, written by an as yet unidentified acquaintance (Fig. 5). This first-hand description notes she “was entirely self-taught, never having had one hour’s regular instruction.” By extension, Betsy Champlain would therefore also be considered to have been self-taught. While a review of late-eighteenth-century New London history does not reveal a local source for formal art training, the sisters likely attended a female academy where they would have attained the basic skills of needlework and painting (See Huber article, which follows). The definition of “formal training,” as used by the author of the obituary, may have been directed to Mary’s having no training with an academic artist; the author not considering a female academy of the same status nor having knowledge of her later experience in New York.

Both Way and Champlain developed an identical miniature-portrait style where a watercolor-painted head, or head and torso, was applied to a contrasting silk background and “dressed” with applied clothing. In addition to this distinctive approach, they also painted miniature portraits in the more traditional manner of portraiture on cardboard or ivory.

Using the signed Mary Way likeness of her cousin and New London newspaper editor Charles Holt as an example (Fig. 6), author William Warren outlined (in part) the specific treatment of eye, nose, and mouth evidenced in the dressed as well as the standard miniatures attributed to Mary Way:

• Scissor work shows well-crafted articulation of nose, curl of the lips, chin, and brow. Cut edges are free of adhesion to underlying fabric, giving an almost three- dimensional impression.

• Painstaking rendition of the face in watercolor.

• Eyebrows close-set to the eye. Wide-open stare with vertically narrowed ovoid lens fronting a well defined triangular sclera area. Delicate upper lashes. Concisely delineated upper and lower eyelid.

• Distinctive handling of the inner ear anatomy resembling a saxophone or ear-trumpet.6

• Dark wash used between the nose and the top lip and on the chin to indicate the subject’s beard.

• A fine line delineation between compressed upper and lower lips.

• Well-defined hair, with explicitly rendered curls for women. A white wash over hair suggesting graying hair and/or a powdered effect.

• Variable tinting and shading of facial tones.

• Highlights done with white lead on skin and on shear painted clothing.

COMPARISON

The portrait of Charles Holt was the first identified Mary Way piece and is the only miniature known to be signed by her. Subsequent examples with applied fabric have all been credited to her hand. However, with the exception of an applied velvet “chapeau bras” or cocked-hat, it is more correctly a scissor-cut miniature portrait adhered to a silk background and not a true fully “dressed” miniature.

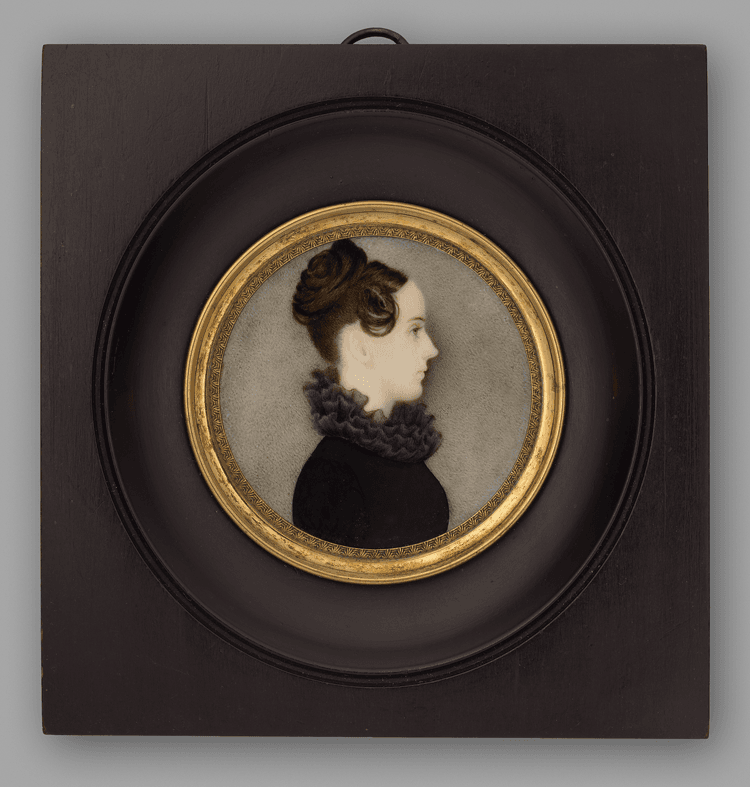

In comparing the Holt portrait by Mary Way to the miniatures of New London native Charles Briggs (Fig. 7), his wife Eliza (Fig. 8), and Mary Hallam Saltonstall Huntington (Fig. 9), each confidently attributed to Betsy Way Champlain,7 it is evident that the sisters used the same facial modeling techniques, described above, with equal proficiency. While a contrasting shade of silk was utilized to offset and highlight the cutout figure of Holt, a similar contrasting hatched halo effect was used on ivory for Charles and Eliza Briggs and on paper for Mary H. S. Huntington. Both sisters also integrated white lead paint highlights in representing shear fabric or under fabric in many of their painted portraits of women.

Similarities between the sisters’ techniques appear to exist as early as the 1790s or possibly before, and raise the question: Who did what—either individually or together—before Mary’s move to New York.

A dressed miniature identified as painted by “Miss Way,” presents just such a conundrum—as well as being the only dressed miniature identified with this designation. The sitter was “Mrs. Lizy Champlain,” Betsy Way Champlain’s mother-in-law.8 The backing has the notations “Miss Way,” “E. Champ,” “Mrs Lizy,” “By Miss,” and “Miss.” The sitter’s outfit suggests a dating as early as 1790. The “Miss Way” references might suggest the single Mary Way as artist, but it seems more likely to have a daughter-in-law or daughter-in-law-to-be perform the commission. If completed just prior to Betsy Way’s wedding in 1794, she could just as well have completed it as “Miss Way.” “E. Champ” may refer to her mother-in-law, or to Betsy after her marriage, since she did sign her married correspondence “E. Champlain.” If the portrait was completed prior to Betsy’s wedding, “By Miss,” and “Miss” could also suggest that the sisters collaborated on the piece.

The four portraits of the Saltonstall family (figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) provide further suggestive evidence of sibling collaboration. Winthrop Saltonstall (fig. 4) and his grandchildren (figs 2–3) are standard dressed miniatures; however, the portrait of daughter-in-law (and the children’s mother) Hannah Sage Saltonstall (fig. 1) is different. Though this portrait features all of the painted characteristics outlined above, it is not “dressed”—the almost full figure image is instead composed of cut paper adhering to a silk background. All four works have the same frames, and along with the portraits of Hannah’s parents, General Comfort Sage and his wife Sarah Hamlin Sage (Figs. e and f), all have the same format, framing, and likely dates of production.9 The close family connections, styling, and framing consistency between these portraits suggest a group commission. The name of Betsy’s husband, “George Champlain” (Fig. 10) is written on the inside back of the oval card securing the black silk background of the Hannah Sage Saltonstall miniature (fig. 1). Betsy Way was married to George Champlain in 1794, predating this grouping of six miniatures by three to four years, since both General and Mrs. Sage died on the same day (March 14, 1799); presumably the commission was completed prior to this date. Did Mary borrow this oval card from her sister? Could the sisters have collaborated on this multi-image commission? It is at least likely that Betsy Champlain painted this, the only non-dressed figure in the related group of six family members.

Mary Way’s first advertisement as an instructor of “reading, writing, plain sewing, [?], and many other kinds of embroidery” was in a November 10, 1796 advertisement in the Connecticut Gazette, published in New London. A similar New London advertisement appeared in 1809, and again two years later when Way was active in New York City. When Way placed her first notice in 1796, she identified her business as being at the residence of a Mrs. Truman. A dressed miniature identified as Deborah (Davis/Dennis) Truman (1720–1801), and a dressed miniature likely to be one of her sons, are both set within the same style of frame10 and share the identifiable Way/Champlain characteristics. A third miniature (Fig. 11) portrays the same woman, who, based on the facial similarities of the other miniature, is also Mrs. Truman. Her “outfit” in both her portraits is comprised of tiffina (thin gauze muslin) for the shawl and head piece, with lead white overpainted detailing. Due to the business association between Way and Truman, it seems apparent that the three dressed miniatures can be firmly attributed to Mary Way, though without such associations, an attribution to a specific sister would not be possible.

Recently located information concerning the “dressed” miniature portrait of Rebecca Saltonstall Mumford (Fig. 12), sister of Winthrop Saltonstall of the previously referenced core group, was described by family genealogist Mary (Webb) Cooch in her 1919 edition of Ancestry and Descendants of Nancy Allyn (Foote) Webb…: “Copy of a miniature painted by Mrs. Champlin of New London, Conn. The peculiarity of this picture is that the muslin and brown satin are real fabrics laid upon the background, and the folds, shadows and ribbons are painted on them.” Comparison of this piece to the portrait of Mrs. Truman (fig. 11) reveals identical handling of the “dressed elements” with the painted enhancements on the Saltonstall miniature even more elaborately rendered. This 1919 reference is the earliest printed recognition of the Way/Champlain style. And most importantly, this pre-1800 image is firmly attributed to Betsy Way Champlain (presumably by information available to the author at the time) placing both she and her sister as equal participants in production of an unique American miniature style.

ARTISTIC EVOLUTION

Presuming the sisters learned the basic skills of needlework and painting at a female academy, the genesis of their artistic bent might have been their own family. Their father, Ebenezer Way II, was trained as a shipbuilder, although there is no record documenting that he practiced this craft. He ultimately became the New London postmaster and a merchant. There, he married Mary Tabor in 1766; she died shortly after Betsy Way Champlain’s birth in 1771. Ebenezer did not remarry until 1783. His unmarried sister Hannah filled this twelve-year span and was “…all the mother I ever knew,” wrote older sibling Mary Way in an August 1825 letter. Aunt Hannah was much beloved by the Way sisters and possessed a degree of proficiency in the use of needle-and-thread, as evidenced in family letters: “…Aunt Hanna…does she still continue to make artificial flowers…” and “…was there ever such a good old soul as she [Aunt Hannah]? I thought I should have laughed myself to death at her little housekeeping mats. They are without exception the prettiest little devils I ever saw, and have made me shed quarts of tears over them.”

There is convincing evidence that grandfather Ebenezer Way I was a trained tailor.11 He was widowed in 1777 and did not remarry. Both of the sisters spent time at the “family mansion,” a farm purchased by Ebenezer I in 1736. There, it is possible that both young ladies had access to fabric, and learned a degree of proficiency in tailoring. There was a precedence for dressed miniatures in England, but the girls would have needed access to such. So, Aunt Hannah and their grandfather may have been the ones to spark the concept of “dressed” miniatures that developed into a Way/Champlain tradition.

A single reference to schooling reveals that both Way and Champlain may have had some education typical for young ladies of the period: “…when we were at singing school they was singing a remarkably fine tune with which we was both delighted.” In the eighteenth century, education for adolescent women consisted of “academy(s) for young ladies” which were either “boarding or day schools.” 12 As previously noted, no such school has been discovered to have existed in New London at the time. However, needlework expert Carol Huber (See Huber article) has noted that a unique piece produced at the Lucy Carew School in nearby Norwich reveals characteristics of the sisters’ style and suggests that one or both of the sisters were associated with the school. A classically styled Way/Champlain dressed miniature of Lucy’s cousin by marriage, Polly (or Molly) Carew (1772–1855), previously attributed to Mary Way by William Warren in his 1992 article, lends further support to a Carew connection.13

The dressed image of Polly strongly encourages consideration for an earlier Carew connection. Polly is a teenager in the portrait, suggesting a production date of 1790 or earlier “making this probably one of the earliest examples of her (Mary Way’s) work,” according to William Warren. Polly’s maternal grandfather John Huntington (1745–1815) of Norwich was the business partner of Lucy Perkins Carew’s husband Daniel. She was cousin to Lucy Perkins Carew via both her mother Mary Huntington Carew’s (1739–1814) lineage14 as well as through her father Eliphlet Carew (1740–?). Thus Polly (Molly) represents a direct and early connection between the Way sisters and Lucy Perkins Carew. In view of their similar ages, it is intriguing to speculate that adolescent Polly, Mary and Betsy may have developed a friendship while attending a Carew day school, and that this early instruction enabled a foundation for the developing Way sisters’ talent.

Even this earliest example of one of the sisters’ work possesses the confidence, skill, and meticulous attention to detail that would come to define a Way/Champlain hallmark style, evolving over the next thirty-five years into the sophisticated artistry apparent in the ivory portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Briggs (figs. 7–8). It is this style and distinctive excellence that made Way and Champlain sought-after professionals in a time when opportunities for women were limited. As each image has come to light and takes its place in an ever evolving portrait album, we are learning more about the story of these uniquely talented “self-taught” sisters who created their own stunning American art form.

Brian Ehrlich is an independent researcher. The author gives thanks to Deborah Child, Carol and Stephen Huber, the Liverants, Butch Berdan, and Lara and Pamela Ehrlich.

Published in the Autumn 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, in tandem with InCollect.com. The digitized version of the entire issue is available on www.afamag.com.

2. The tradition of miniatures decorated with applied fabric has a tradition in late eighteenth-century England. The Way sisters are the only American miniaturists who handled the craft as a career.

3. Way-Champlain Family Correspondence, 1792–ca. 1904. American Antiquarian Society; gift of Ramsay MacMullen, 2005. See his publication: Sisters of the Brush (Past Times Press, New Haven, Conn., 1997). The family papers are the source for all quoted material in the article, unless noted otherwise.

4. Details on the six other family portraits may be found as follows: Sage/Saltonstall family: see MacMullen, Sisters of the Brush, notes to Chapter 2, end note 2. Coit Sisters: MacMullen, 35, and notes to Chapter 3, end note 6. The locations of these miniatures are currently unknown, but MacMullen had access to images of the Sages/Saltonstalls and access to family letters that discuss the Coit sisters.

5. See entry on Mary Way, in Carrie Rebora Barratt and Lori Zabar, American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met, 2010), 76.

6. Personal discussion with the late Robert Thayer, Americana Dealer and Antiquarian.

7. Robin Jaffe Frank, in Love and Loss (Yale University Press, 2000), attributes the ca. 1820 portraits of Charles Briggs and his wife Eliza “Bassal Meiller” to Mary Way. By 1820, however, Mary Way was blind in one eye with significant impairment in vision in her other eye. She was not painting at this time. Betsy, however, was fully active as an artist in New London.

The image of “Mary Hallam Saltonstall Huntington”(fig. 9) descended in the Sage-Saltonstall Family; sold at Litchfield Auction Gallery, 1991. Hand written note on the back states the portrait is of “Mrs. Sallie Sage, wife of General Comfort Sage of Middletown.” The subject’s clothing and hair style date to the early 1800s, therefore this is not an image of Sarah “Sallie” Sage, who is actually figure f, or her daughter Hannah Sage Saltonstall (fig. 1). The only age appropriate person with this direct line of descent is Mary H.S. Huntington (fig. 9). The associated Betsy Way Champlain miniature of Mary’s daughter, Mary (Fig. j), dating to circa 1814, strongly suggests mother and daughter were painted at the same time. The family was residing in North Bridgewater Mass. However, both Mary’s and husband Daniel’s families were in New London where Betsy Way Champlain likely painted the portraits. There is no data for a N.Y.C. connection, where Mary Way was residing in 1814; thus these portraits are connected with Betsy.

8. MacMullen, figs 2, 18; endnote 5.

9. The six miniatures have a sight-size of 3¼ x 4 inches, with the same tin-stamped decoration applied over oval wooden frames. Five of the pieces are mounted on a black fabric background with red fabric utilized for the image of Winthrop Saltonstall.

10. The identified dressed miniature of Mrs. Truman along with a dressed miniature

of one of her two sons, are in the collection of the New London County Historical Society; his image is illustrated in the Warren article, page 549. Prior research in 1996–1997 identified the sitter of the female portrait as Deborah Davis/Dennis Truman, based in part on the associated “young man” with the same format and framing. The birth dates of Deborah’s two sons match the projected adult age of this male who is likely one of the two. The Way sisters’ aunt-by-marriage was Mary Way Truman, but she and her family had moved to Sheffield, Mass., between 1748 and 1753, where they were residing at the assumed dating of the three miniatures.

11. “Way Hill Road, Waterford” The Day (Newspaper), June 10, 1936. “The Diary

of Joshua Hempsted” (New London County Historical Society, 1999), 453.

12. Davida Tenenbaum Deutsch’s “John Brewster, Jr.: “An Artist for the Needleworker” in The Clarion (Fall 1990, Vol. 15, No. 4): 46.

13. For an image of Polly Carew, see Magazine Antiques (October 1992): 542.

14. Simon Huntington (1629–1681), married to Sarah Clark, produced three sons. Son Joshua Huntington (1698–1741) married Lucy Perkins Carew’s great-aunt Hannah Perkins (1701–1745). Son Ensign James Huntington (1680–1729) was great-grandfather of Polly Carew. Polly and Lucy Perkins Carew were cousins by marriage.