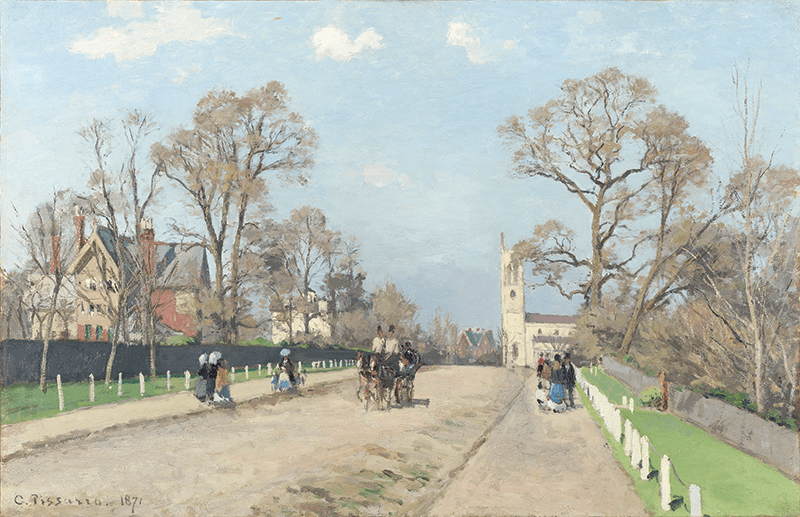

Paul Durand-Ruel: Champion of the Impressionists

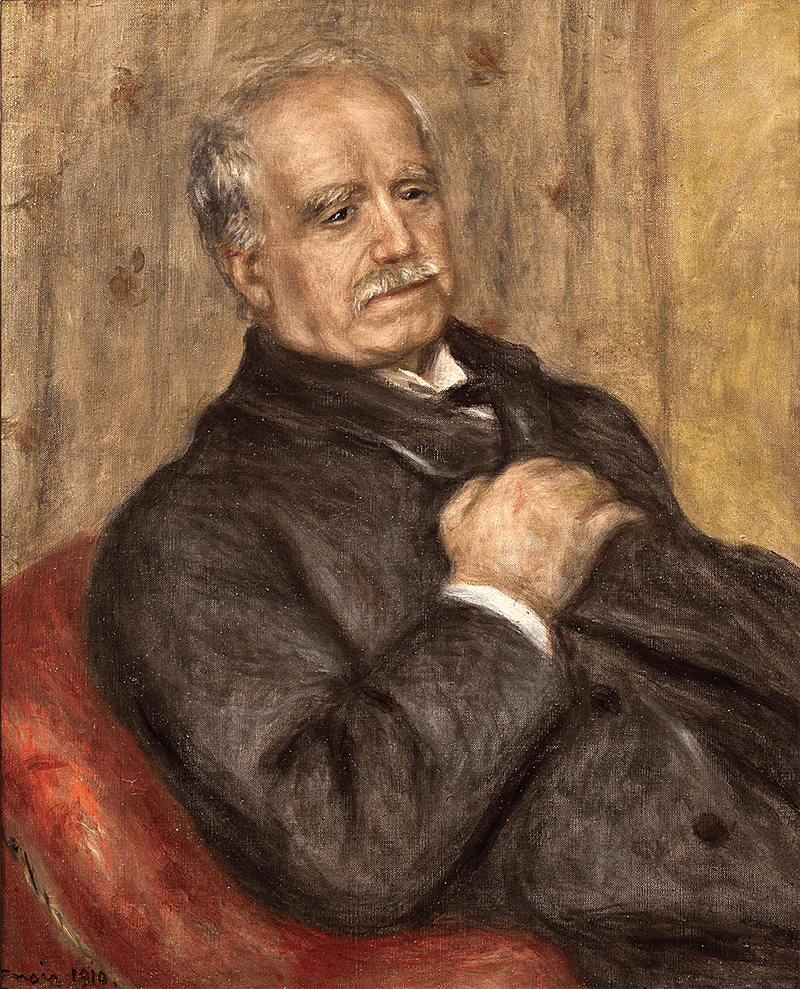

- Fig. 1: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Paul Durand-Ruel, 1910. Oil on canvas, 2513⁄16 x 217⁄16 inches.

Courtesy of Archives Durand-Ruel

© Durand-Ruel & Cie.

Durand-Ruel was nearly seventy-nine years old and finally enjoying success in selling Impressionist works when his friend Renoir painted this sensitive portrait.

In 1924, at age eighty-three, Claude Monet was asked to recount the difficult early years when he and his fellow Impressionists were ridiculed for their loose brushwork, lack of finish, and modern subject matter. “We would have died of hunger without Durand-Ruel, all we Impressionists,” he said. “We owe him everything.” 1 He was referring to the Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922), who for fifty years tirelessly promoted the canvases of Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and other leading artists of the French modern school. Ironically, the art dealer (Fig. 1) whose adept marketing brought acclaim to the Impressionists is less known today than the artists he championed, a circumstance that an exhibition in Philadelphia seeks to redress.

Durand-Ruel’s deep conviction in the work of the Impressionists led him to buy more than 5,000 of their canvases and kept him on the verge of bankruptcy for decades. A staunch royalist and Catholic, whose first career choice had been to become a missionary, Durand-Ruel seemed an unlikely advocate for a group of innovative artists whose political and religious beliefs were far different from his own. In 1865, the thirty-four year old inherited his parents’ art gallery in Paris and its respected stock of paintings by such Salon favorites as William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier. While these artists provided a stable income, Durand-Ruel made his first risky investments with the lesser known Camille Corot, Gustave Courbet, Theodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Eugène Delacroix. The bold colors, plein air painting techniques, and sometimes controversial subject matter of these artists meant that their paintings required patience and hard work to sell, but Durand-Ruel realized significant profits with them and earned a reputation for selling works of quality and inventiveness. He might happily have devoted his entire career to promoting these artists were it not for a series of unexpected encounters in the early 1870s.

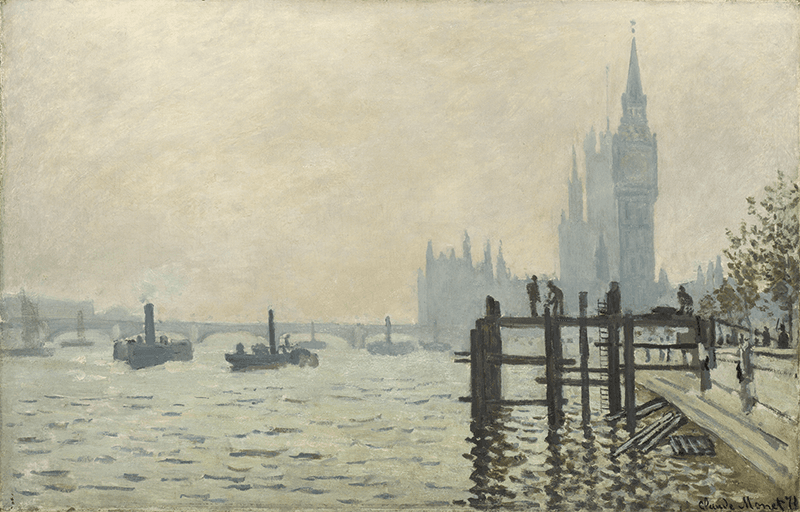

- Fig. 2: Claude Monet (1840–1926), The Thames below Westminster, ca. 1871

Oil on canvas, 18½ x 28¾ inches.

Courtesy of The National Gallery, London: Bequeathed by Lord Astor of Hever, 1971.

The canvases that Monet painted in London in 1871 are noted for their small size and powerful broken brushwork that startled contemporaries accustomed to more highly finished works.

- Fig. 4: Alfred Sisley (1839–1899), The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne, 1872.

Oil on canvas, 19½ x 25¾ inches.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Ittleson Jr., 1964. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY.

Durand-Ruel purchased this dazzling summer scene from Sisley in August 1872, among the earliest works he acquired from the artist.

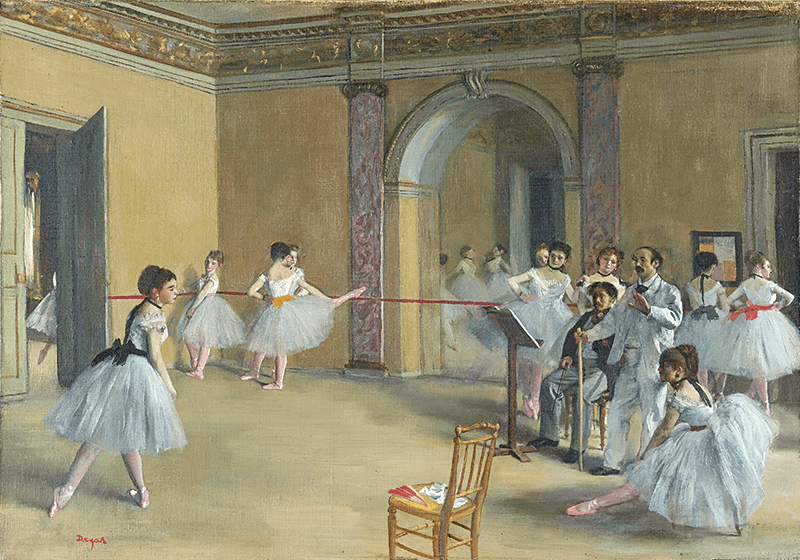

- Fig. 5: Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917), The Dance Foyer of the Opera at the rue Le Peletier, 1872,

Oil on canvas, 12⅞ x 18¼ inches.

Courtesy of Musée d’Orsay, Paris: Bequeathed by Count Isaac de Camondo, 1911. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Photo: Hervé Lewandowski.

Recognizing the appeal of Degas’ dance subjects, Durand-Ruel acquired this work from the artist for a substantial 2,500 francs in August 1872.

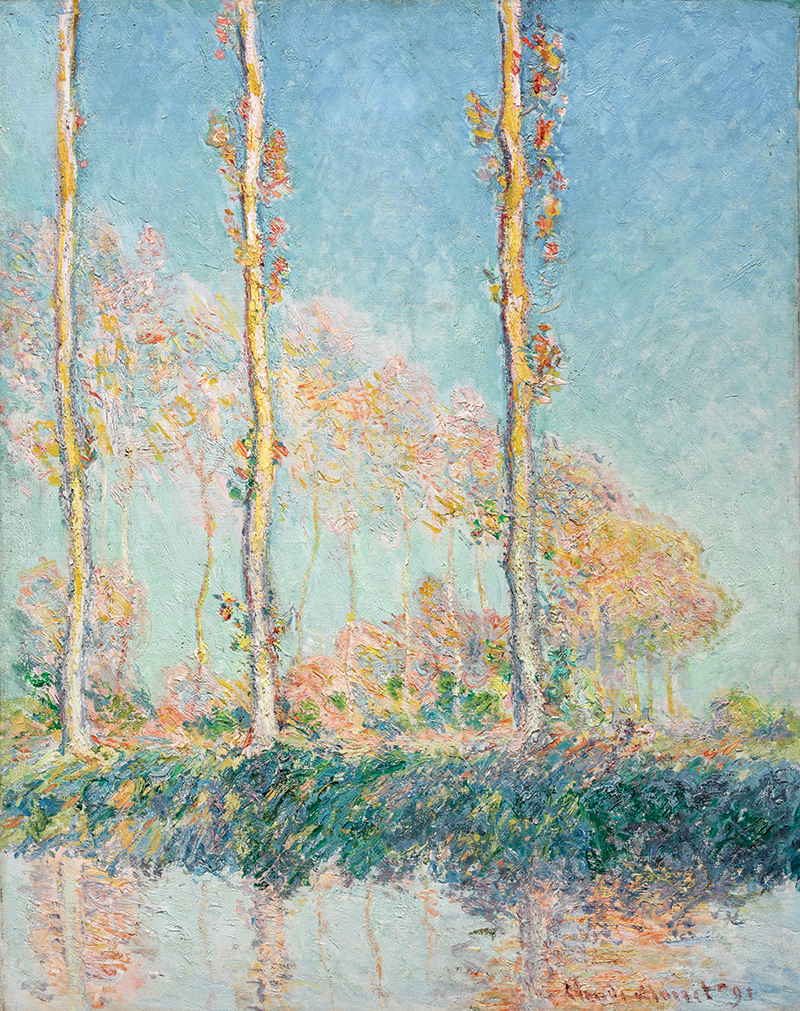

In September 1870, Napoleon III was defeated by the Prussians at Sedan, in northern France, forcing Durand-Ruel to send his wife and children to the safety of southwestern France, while he and much of his gallery stock went to London. Hoping to profit from Britain’s more stable political climate, he opened a gallery on New Bond Street. Among his fellow refugees from Paris was the landscape painter Charles Daubigny, who introduced the dealer to Claude Monet, saying, “This artist will surpass us all.” 2 Monet, too, was spending the war in London, painting images of urban life along the River Thames with a beauty and boldness (Fig. 2) that captivated Durand-Ruel, who immediately began to acquire them. Monet’s good fortune reached the ears of Camille Pissarro, who days later left a painting at the Durand-Ruel Gallery. The dealer asked him to name his price for it and send others (Fig. 3). Durand-Ruel began slipping Impressionist paintings into his exhibitions, providing the artists with critical income and a venue for their works.

Durand-Ruel’s association with the Impressionists broadened on his return to Paris in late 1871, when he met Renoir, Sisley, and Degas (Figs. 4, 5), buying as many as twenty or thirty canvases from them a year. At the same time, Durand-Ruel discovered the work of Édouard Manet, whose dramatic lighting and references to older Spanish and Dutch masters were often underscored by unsettling modern subjects such as a pivotal naval battle of the American Civil War (Fig. 6). In January 1872, Durand-Ruel bought twenty-three canvases from Manet’s studio for 35,000 francs, an extraordinary windfall for the artist in a period when the average French worker made 900 francs a year. It was a courageous gamble for Durand-Ruel at a time when there was no established market for Manet.

- Fig. 6: Édouard Manet (1832–1883), The Battle of the U.S.S. “Kearsarge” and the C.S.S. “Alabama,” 1864.

Oil on canvas, 54¼ x 50¾ inches.

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art: John G. Johnson collection, cat. 1027.

A critical battle of the American Civil War occurred off the coast of France in June 1864 when a Union warship sank a Confederate raider.

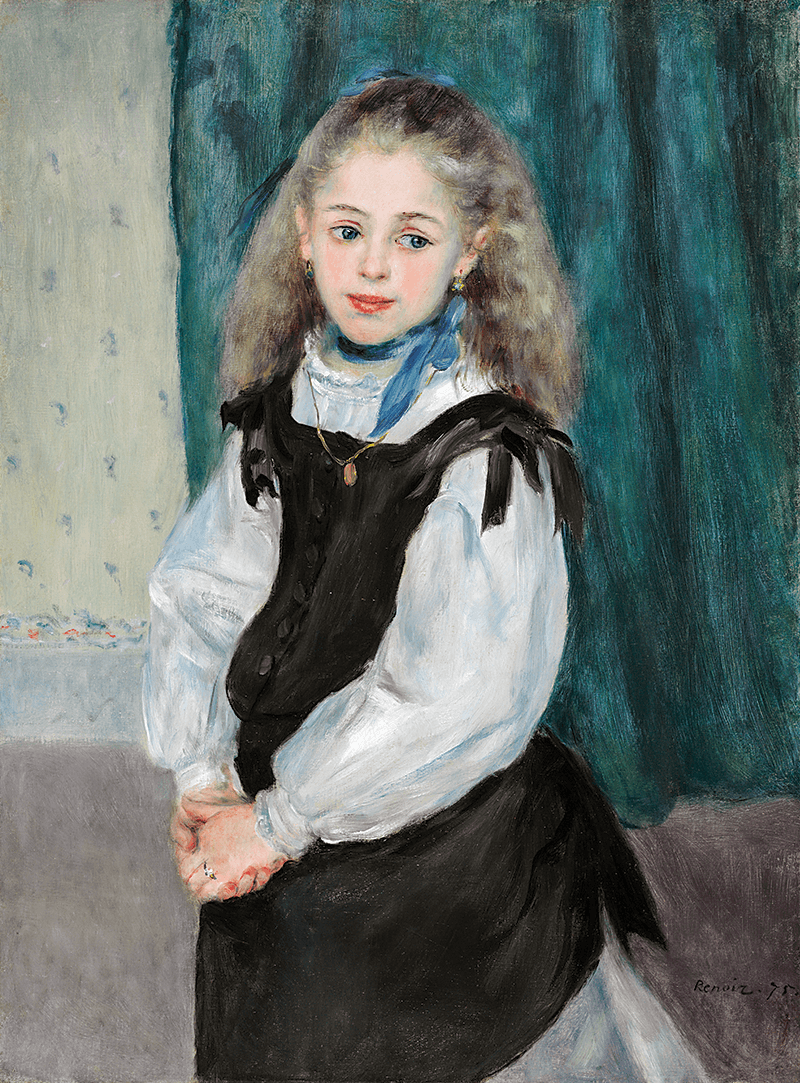

- Fig. 7: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875.

Oil on canvas, 32 x 23½ inches.

Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny, 1986-26-28.

Unable to acquire many Impressionist paintings in the mid-1870s, Durand-Ruel instead offered the group his gallery as a venue for their second Impressionist exhibition in 1876.

- Fig. 9: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Road at La Cavée, Pourville, 1882.

Oil on canvas, 23¾ x 32⅛ inches.

Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Bequest of Mrs. Susan Mason Loring, 1924.

Monet’s recent landscapes from Normandy formed a significant part of his first solo exhibition in Durand-Ruel’s Gallery where critics admired their compositions.

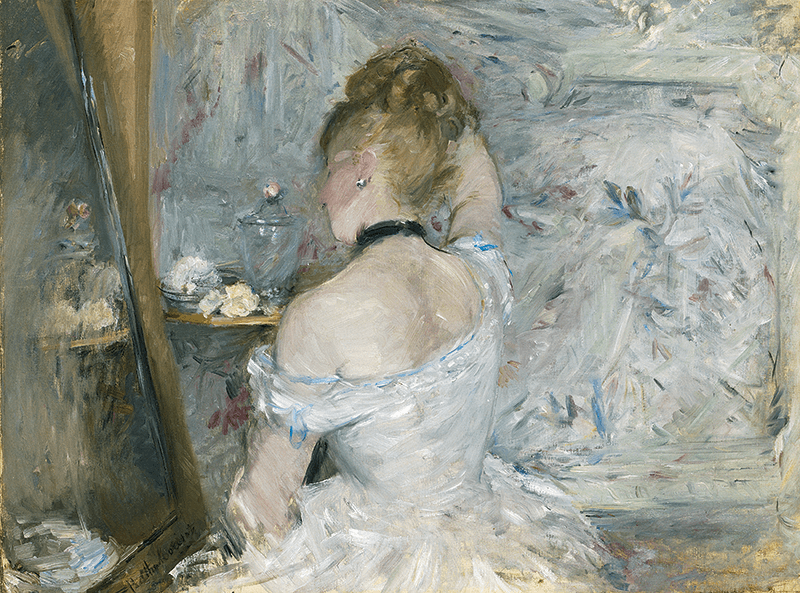

- Fig. 11: Berthe-Marie-Pauline Morisot (1841–1895), Woman at Her Toilette, ca. 1875–1880.

Oil on canvas, 23¾ x 31⅝ inches.

Courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago: Stickney Fund.

Exhibited in New York in 1886, Morisot’s sensuous view of a woman adjusting her hair was acquired there by American artist William Merritt Chase.

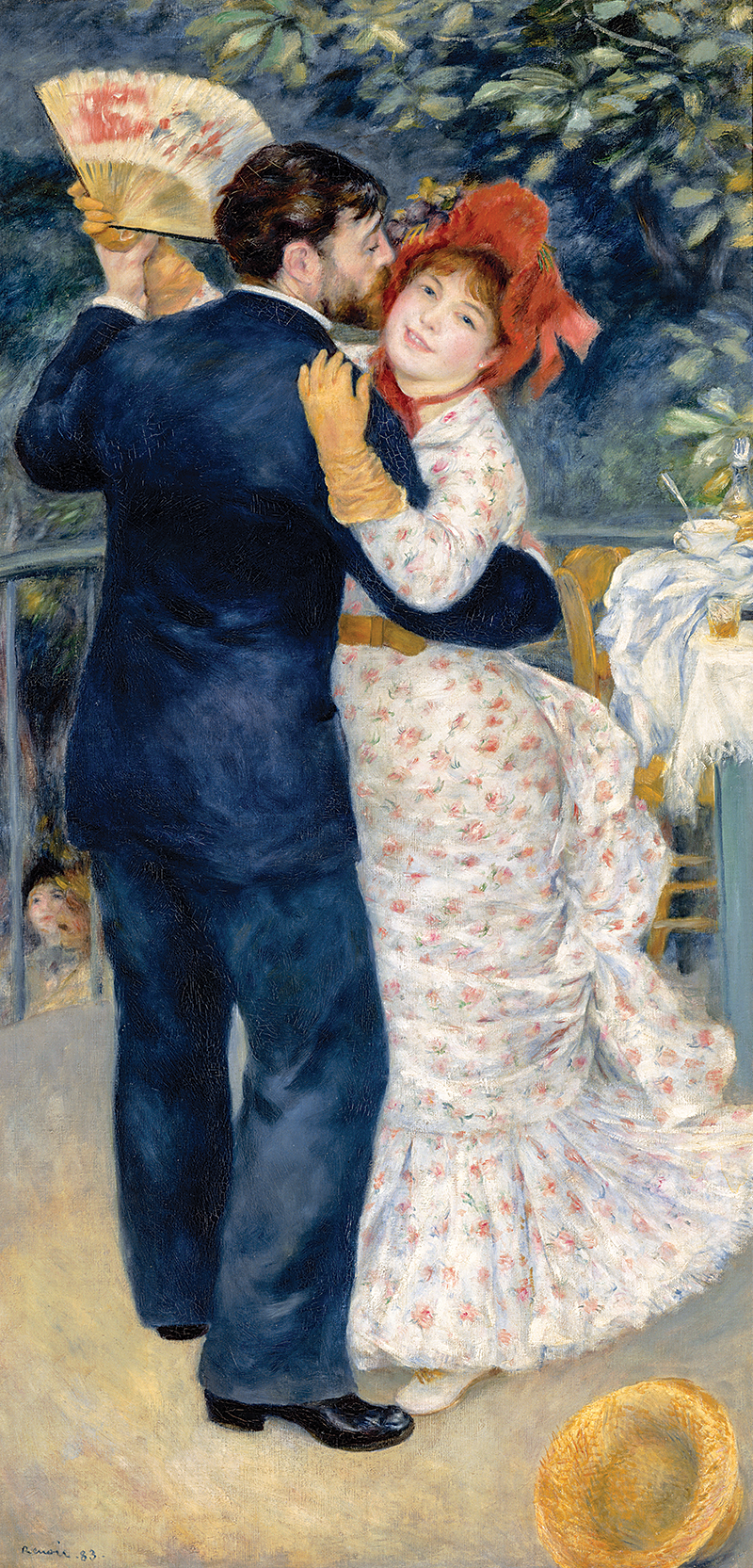

- Fig. 8: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Dance in the Country, 1883. Oil on canvas, 70-⅞ x 35-7⁄16 inches.

Courtesy of Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY / Photo: Hervé Lewandowski.

Durand-Ruel’s private apartment, a place where he entertained clients, contained some of the finest Impressionist canvases from his stock, including this pair of dancers by Renoir.

In the mid-1870s, an economic crisis forced Durand-Ruel to halt his large-scale Impressionist purchases. He turned his attention to promoting the Impressionists in other ways, developing business strategies that set the foundation for the modern art market (Fig. 7). Ambitious exhibitions, auctions, gallery lectures, and publications became defining aspects of his gallery’s practice. During this period, Durand-Ruel developed close personal ties with his artists, offering advice and encouragement, commissioning work from them for his home, and collaborating with them on new ways of exhibiting their work (Fig. 8). This facet of the dealer’s activities came to the fore in the 1880s, when he launched a series of shows, each lasting about three weeks, that focused on the work of a single artist and were usually accompanied by a catalogue. The exhibition devoted to Monet in March 1883 is a vibrant example of the way in which dealer and artist collaborated: Monet was initially reluctant to exhibit his work alone, perhaps fearful of the criticism he might have to bear on his own. But Durand-Ruel persuaded the artist that it could establish his critical reputation, and he helped Monet assemble more than fifty representative paintings (Fig. 9). Though no works sold, exhibition reviews were favorable and the public began to recognize Monet’s unique talent. Solo exhibitions, widely imitated by rival galleries, became a Durand-Ruel Gallery trademark (Fig. 10) and remain common today.

Usually associated with Paris, the home of his principal galleries, Durand-Ruel was a cosmopolitan figure who relentlessly pursued opportunities in Austria, Russia, Belgium, England, Germany, and the United States. A first wave of expansion occurred around 1870 when he traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia; opened the gallery on New Bond Street, London; and began to exhibit work in Brussels. The collapse of the Union Générale bank and with it the Paris Stock Exchange in 1882 sparked further difficulties for Durand-Ruel but also inspired a new series of ventures in foreign markets.3 To an exhibition in Boston in September 1883, he sent eighty academic and romantic paintings, among which a handful of Impressionist works were interspersed. A month later, the Berlin dealer Fritz Gurlitt displayed twenty-four paintings by Manet, Degas, Monet, Mary Cassatt, and Berthe Morisot from Durand-Ruel.

The gallery’s expansion to America, initiated in the spring of 1886 with an historic exhibition of 289 Impressionist paintings at the American Art Association and the National Academy of Design in New York (Fig. 11), was followed a year later by the opening of a satellite gallery on Fifth Avenue. The American branch persisted for more than six decades and proved vital to Durand-Ruel’s business. “Without America, I would have been lost, ruined,” he later said.4 In America, he discovered a select but bold group of collectors, among them, Alexander Cassatt in Philadelphia, H.O. and Louisine Havemeyer in New York, and Bertha and Potter Palmer in Chicago. Well-respected individuals, their purchases of works by Degas, Monet, and Renoir helped to turn the tide in favor of Impressionism. When the Anglo-German collector Harry Kessler met Durand-Ruel in Paris in November 1903, he asked how the dealer had achieved success with Impressionism. Durand-Ruel explained that through “bluffing” he had demanded $1000 for Monets in New York in 1886. Although he hardly sold any, he was able to claim in France “that he had sold Monets for $1000 in America, and that gave the French collectors courage. It was then that the turnaround took place.” 5

With persistence and agility, the gallery promoted Impressionism throughout Europe and America and was able to win over the skeptical. The Durand-Ruel Gallery lent paintings to expositions and world’s fairs in St. Louis, Chicago, and New Orleans, borrowed rooms from fellow dealers such as J. Eastman Chase in Boston, Thurber’s Art Gallery in Chicago, and Gillespie’s Galleries in Pittsburgh for short-term exhibitions, and temporarily turned hotel rooms in Denver, Chicago, and Pittsburgh into exhibition spaces. In nearly all these places, Durand-Ruel showed works by Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, and Degas to receptive audiences, often benefiting from the enthusiasm of artists like Cassatt (Fig. 12), John Singer Sargent, and William Merritt Chase, who bought Impressionist works themselves and encouraged others to do the same. By the mid-1890s, hundreds of Impressionist canvases could be found in American collections and increasingly in its museums, thanks to Durand-Ruel’s efforts. Thus, he was able to write in 1911: “My madness had been wisdom.” 6

Discovering the Impressionists: Paul Durand-Ruel and the New Painting can be seen at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from June 24 to September 13, 2015. It features more than ninety paintings and sculpture once part of the dealer’s stock. It recreates pivotal exhibitions and key moments in the Impressionist movement with canvases by Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Manet, Cassatt, Morisot, and others. Organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, The National Gallery, London, and the Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay, the exhibition has been seen by audiences in Paris and London.

Jennifer A. Thompson is The Gloria and Jack Drosdick Associate Curator of European Painting before 1900 and the Rodin Museum, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

2. M. de Fels, La Vie de Claude Monet (Paris, 1929), 130.

3. Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs of the First Impressionist Art Dealer, ed.

Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 155.

4. Royal Cortissoz, Personalities in Art (New York, 1925), 269–70.

5. Diary entry for November 30, 1903, Harry Kessler, Journey to the Abyss: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler, ed. Laird M. Easton (New York: Knopf, 2011), 313.

6. Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs, xi.