The American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

|

|

Frank Lloyd Wright room built for Mr. and Mrs. Francis W. Little, Wayzata, Minnesota, 1912–1914. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art; purchase, Emily Crane Chadbourne Bequest, 1972 (1972.60.1). |

|

by Morrison H. Heckscher

Art may be eternal, but what it means to people isn’t, and that’s why each generation displays it differently. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which first exhibited the arts of colonial America precisely one hundred years ago, is once again in the midst of transforming the way it shows the nation’s artistic patrimony.

In 1909, on the occasion of New York State’s Hudson-Fulton Celebration, the museum mounted a temporary display of furniture, silver, ceramics, and family portraits that spoke to the Colonial Revival’s romanticism of the American past. In 1924 it opened an American Wing, a permanent three-story home for period rooms and their furnishings that signaled a desire to inculcate new European immigrants with traditional Anglo-American values. And in 1970, in honor of its own centennial, the museum mounted19th Century America, broadening the scope of its collections with a focus on aesthetic quality. That exhibition was a dry run for the addition to the American Wing in 1980, which served to incorporate permanent displays of paintings and sculpture as well as later nineteenth-century decorative arts. Today, nearly forty years later, the combined structures, together with the collections they house, are being rethought for twenty-first century audiences.

|

Rendering of the Charles Engelhard Court, The New American Wing. Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates, 2008. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

Five years ago in these pages I outlined the changes then being contemplated: reconfiguring the Charles Engelhard Court to better showcase the art therein; reordering two centuries of historic interiors into a coherent chronology; designing all new galleries for paintings; and otherwise improving visitor experience.1 I also mentioned that the American Wing had a “curatorial staff of unsurpassed ability and experience.” It is thanks to the wholehearted engagement of these, my colleagues in this effort, that as of May 19, 2009, the Charles Engelhard Court and the full run of period rooms (from 1680 Massachusetts to 1915 Minnesota)––now transformed to show to best advantage the museum’s holdings of American sculpture and decorative arts––are once again open to visitors. (The paintings galleries will reopen in 2011.) In the following pages the responsible curators will comment on aspects of the new installations: Amelia Peck on period rooms in general; Peter Kenny on the new New York Dutch Room in particular; Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen on the stained glass and (with Adrienne Spinozzi) a new gift of ceramics; Beth Wees on silver and jewelry; and Thayer Tolles on marble sculpture.

1. Heckscher, “The American Wing of The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” in Antiques & Fine Art, vol. IV, no. 6 (Fourth Anniversary, January/February 2004): 234–235.

Morrison H. Heckscher is the Lawrence A. Fleischman Chairman of the American Wing.

|

|

by Amelia Peck

| |

Fig. 1: Samuel Hart Room, Ipswich, Massachusetts, 1680. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Munsey Fund, 1936 (36.127). |

The American Wing’s nineteen furnished period rooms provide an unparalleled tour of American domestic architecture and interior design from the seventeenth century (the Hart Room, 1680 [Fig. 1]) to the twentieth century (the Frank Lloyd Wright Room, 1912–1914 [see page 134]). The motivation for the recent renovation of many of the earlier rooms was to encourage visitors to see the Wing’s interiors in chronological order so they can make visual and historical connections as they enter each space. The entire tour of rooms, spanning three centuries, cannot be experienced at any other museum, but the layout of the American Wing, as redesigned in 1980, made the path hard to follow. The addition of a new glass elevator will now bring visitors directly to the third floor to begin their tour, and new signage will make the walk through our American interiors and decorative arts galleries more lucid and coherent.

In addition to rationalizing the visitor experience, many other changes, some obvious, some “behind the scenes” were made. We removed five rooms that were deemed of insufficient architectural interest or integrity. Two eighteenth-century period rooms (the Verplanck Room, 1767 [Fig. 2], and the Marmion Room, 1756), moved from the American Wing’s 1924 core in 1980, were returned to their rightful places in the chronology. A new room, from the 1751 Daniel Peter Winne house near Albany, New York, has been added (see page 139).

New research has led to changes in the appearance or interpretation of several of the rooms. After extensive paint analysis, the Hewlett Room, the Verplanck Room, and the Alexandria Ballroom were repainted using historically accurate oil paints applied with historically accurate methods. Research into family documents and the use of the science of dendrochronology (tree ring dating) proved that the Hart Room (1680) was actually about twenty years younger than we thought it was, thus proving it belonged to Samuel Hart, rather than his father, Thomas.

|

Fig. 2: Verplanck Room, New York, 1767, with new interactive computer label system. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, by exchange, 1940 (40.127). |

Important updates to the air handling and fire suppression systems will favorably affect the visitor experience as well as the conservation and preservation of the rooms and objects. And in an innovative program debuting in the American Wing, touch-screen computers (see fig. 2) will allow visitors to access information about the objects displayed, the architecture of the house that the room came from, the original owners of each room, and the history and installation of the room after it came to The Metropolitan Museum.

Amelia Peck is the Marica F. Vilcek Curator, Department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

|

Fig. 1: View of Van Rensselaer Hall, Albany, N.Y. constructed 1765–1769. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. William Bayard Van Rensselaer in memory of her husband. |

|

A New York Dutch Room for the American Wing

by Peter M. Kenny

| |

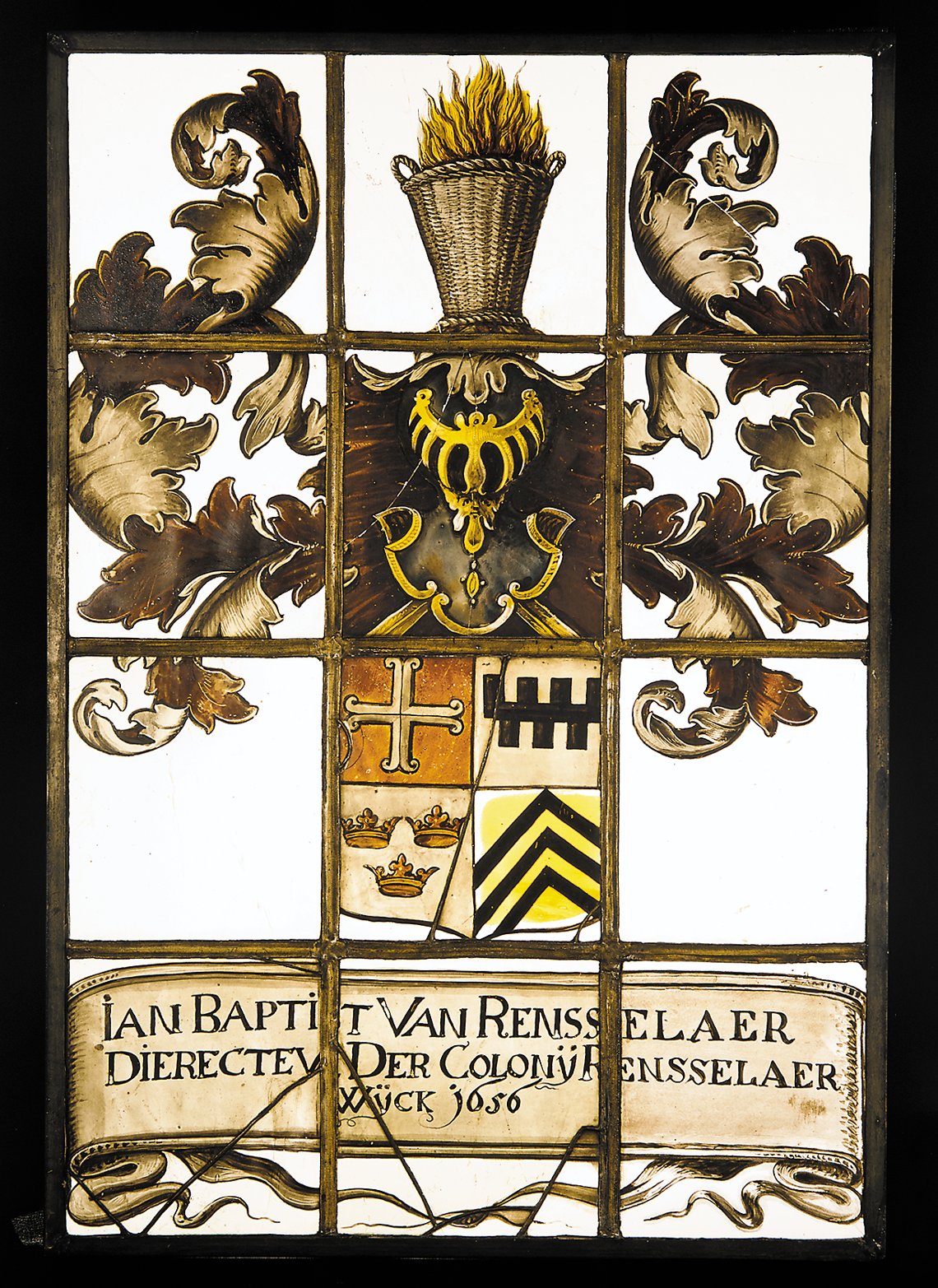

Fig. 2: Painted window made by Evert Duyckinck (ca. 1620–ca. 1700) New York City, ca. 1656. Decorated with the Van Rensselaer coat of arms, 22⅜ x 15½ inches. This window was a gift in 1656 to the Dutch Reformed Church of Beverwyck (later Albany) from Jan Baptist Van Rensselaer (ca. 1629–1678), director of the manor of Rensselaerwyck. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair. |

Since 1928 the American Wing has been home to Van Rensselaer Hall, one of the finest colonial interiors in America (Fig. 1). It was once part of the English Palladian style country house built by Stephen Van Rensselaer II on the manor of Rensselaerwyck in 1769. This enormous estate surrounding the city of Albany, established by a Dutch West India Company charter in 1629, was managed from afar by Kiliaen Van Rensselaer (1595–1646), the first patroon, who sent his sons to direct its activities (Fig. 2).1 In the mid-1600s, hundreds of settlers from throughout the Low Countries of Europe came to settle at Rensselaerwyck.

Among the earliest was Pieter Winne, also known as Pieter the Fleming, from Ghent, who arrived in the early 1650s. In 1653 he married Tanneke Adams, from Leeuwarden in the province of Friesland in the Netherlands, who bore him twelve children.2 Honorable, industrious and energetic, Winne farmed, ran a sawmill, engaged in the fur trade, and was appointed to five terms as a magistrate on Van Rensselaer manor between 1672 and 1690.

Winne and his family were favored tenants on the manor. Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, son of the founder of Rensselaerwyck, was tutor to Winne’s youngest son, Daniel Pietersz (ca. 1675–1757). When young Daniel inherited his father’s life-tenancy on the land, his home, and his sawmill, he was granted additional land upstream, where, in turn, his son, Peter Daniel (1699–1759) and grandson, Daniel Peter (1720–1800), built homes; the former circa 1725 (the house still stands in present-day Bethlehem, New York, about five miles south of Albany) and the latter in 1751; Daniel Peter’s home was part of the last generation of houses built in the time-honored anchor bent framing tradition of the New York Dutch (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3: View of the New York Dutch room, Albany County, N.Y., from the Daniel Peter Winne house, 1751. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Emily Crane Chadbourne fund (2003). |

Threatened with imminent destruction in 2002, the 1751 Daniel Peter Winne house was purchased by the historic preservation firm of J. M. Kelley Limited, Niskayuna, New York, and subsequently sold to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.3 Superbly documented and meticulously dismantled, the main dwelling chamber was reconstructed on the third floor of the American Wing by the Kelley firm under the supervision of the curatorial staff, where it now joins two splendid English-style framed seventeenth-century New England rooms from Ipswich, Massachusetts, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Temporarily closed while phase three of the American Wing renovation project is underway, the Van Rensselaer’s Hall will reopen early in 2011, only a few short steps from the main dwelling chamber of the New York Dutch house occupied by Daniel Peter Winne. If only one of the Van Rensselaer patroons could return today, he might just say, “I remember the Winnes well,” and tell us tales of their days on the manor of Rensselaerwyck.

1. Samuel George Nissenson, The Patroon’s Domain (1937; reprint Octagon Books, New York, 1973), 28. For more on Rensselaerwyck see www.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/na/rensselaerswyck.html. Note that the name has various spellings.

2. Biographical information on Pieter the Fleming and later generations of the Winnes is derived from research reports commissioned in 2003 from Peter M. Christoph of the New York Historical Manuscripts Project, and now in the curatorial files, department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

3. The original house consisted of two main rooms. The Met retained the main dwelling chamber and donated the framing for the other original room, a smaller room without a jambless fireplace, to the New York State Museum in Albany, where it is currently in storage.

Peter M. Kenny is the Ruth Bigelow Wriston Curator of American Decorative Arts and Administrator of the American Wing.

|

|

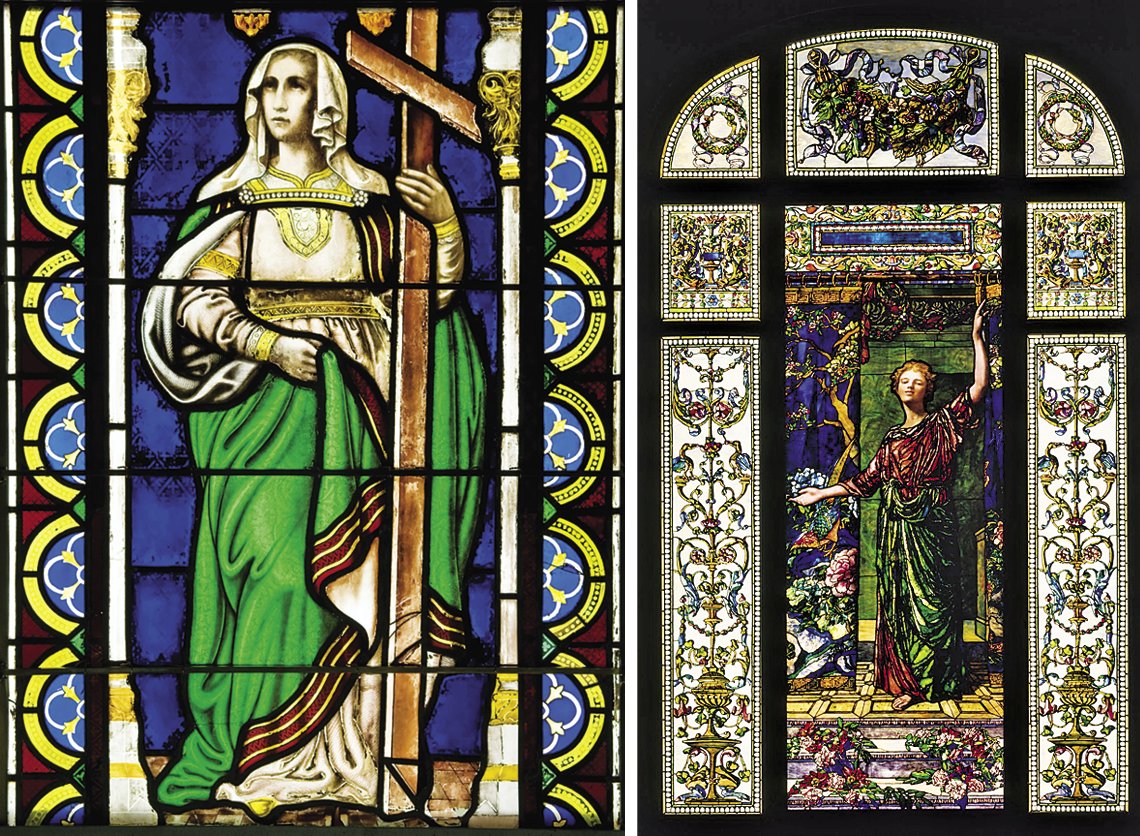

| Left: Fig. 1: Faith and Hope (detail), Henry E. Sharp (active ca. 1850–ca. 1897), New York City, 1867–1869. Painted and stained leaded glass, 168 x 86 in. Gift of Packer Collegiate Institute Inc., 2002 (2002.232.1). Photography courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: Fig. 2: Welcome, John La Farge (1835–1910), New York City, 1909. Painted and leaded opalescent glass, 156 x 96 in. Anonymous Gift, 1944 (44.90). Photography courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

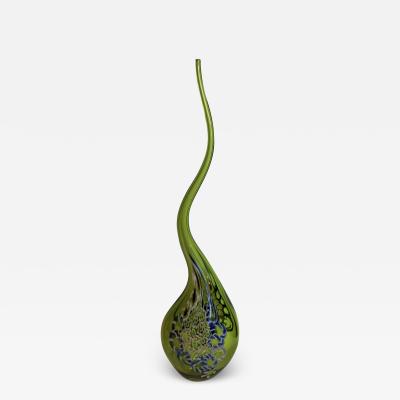

by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen

The new Charles Engelhard Court features the country’s most comprehensive collection of American stained glass dating from the mid-nineteenth to the early-twentieth century. The earliest is the organ loft window by William Jay Bolton and his brother John Bolton for Holy Trinity Church (now St. Ann and the Holy Trinity), in Brooklyn, New York, the Gothic Revival structure designed by Minard Lafever and completed in 1846.

In the early 1850s, Henry Sharp (active ca. 1850–ca. 1897) joined America’s fledgling stained-glass industry that was beginning to flourish in New York. He provided windows for Renwick and Sands’ newly built St. Ann’s Episcopal Church, another grand Gothic Revival structure in Brooklyn, completed in 1867. Faith and Hope, seen here in this detail of one of the figural panels (Fig. 1), is typical of the period in its use of richly colored glass: the brilliant green of the damask robe of the figure displayed on a deep blue background, and the elaborate costume details in silver stain.

John La Farge (1835–1910) and Louis Comfort Tiffany pioneered a totally new kind of window, with new subject matter and a new kind of opalescent glass. The courtyard showcases masterpieces from their two studios. Completed a year before La Farge’s death, Welcome was one of the crowning achievements of the artist’s multifaceted career (Fig. 2). Commissioned in 1908 by Mrs. George T. Bliss for the grand stairway of her New York town house at 9 East Sixty-eight Street, the large allegorical figural panel is framed by decorative panels of garlands and Pompeian ornament. The maiden in classical garb draws back an exotic portiere, a replication in glass of a Chinese textile that originally hung in the Bliss home. When the window was finished in November 1909, La Farge immodestly exclaimed to Mrs. Bliss, “I think it is the finest piece of glass ever made.”

|

Left: Fig. 3: Window from the James A. Patten House, George Washington Maher (1864–1926) and Louis J. Millet (1856–1923), Evanston, Ill., 1901. Leaded glass, 50¼ x 21⅜ in. Gift of American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation, in honor of Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, 2008 (2008.535). Photography by Joseph Coscia Jr., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: Fig. 4: Windows from the Avery Coonley Playhouse, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), Riverside, Ill., 1912. Leaded glass, zinc came, 86¼ x 28 x 2 in. Purchase, the Edgar J. Kaufmann Foundation and Edward C. Moore Jr. Gifts, 1967 (67.231.1–.3). Photography courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

A new mezzanine level in the courtyard suggested the installation of three significant windows of the early twentieth century. With ample use of transparent glass, they will now — as originally intended — look out to a verdant landscape. The most recent acquisition is a panel dating to about 1901 by George Washington Maher (1864–1926) and Louis J. Millet (1856–1923) for the James A. Patten house in Evanston, Illinois (Fig. 3). Maher, a leading practitioner of the Prairie School of architecture, designed the exterior and every element of the interior of this grand house; this panel is one of three Maher designed for the great room. He espoused the “motif rhythm” theory, repeating one element — in this case the thistle — in varying degrees of proportion, detail, and materials.

The Maher window joins three Prairie-style panels by Purcell and Elmslie, considered the second most important firm of the Prairie School after Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), and iconic windows by Wright from the Avery Coonley Playhouse in Riverside, Illinois (Fig. 4). A marked contrast to Wright’s early designs derived from nature, the Playhouse windows are purely geometric in composition and feature bright, mostly primary colors. The unusual design, which Wright later referred to as a “kinder-symphony,” may have been inspired by a parade; the colored glass simulates a haphazard, yet controlled, arrangement of balloons, confetti, and flags. These windows join other superb examples seen in a new light in the new Charles Engelhard Court.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen is the Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wang Curator of American Decorative Arts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

|

Fig. 1: Cornelius Kierstede (1674–ca. 1757), two-handled bowl, New York City, 1700–1710. Silver. H. 5⅜, Diam. 1313⁄16 in.; 25 oz. 19 dwt. (806.9 g). Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Samuel D. Lee Fund, 1938 (38.63). |

|

by Beth Carver Wees

Visitors to the reinstalled balcony overlooking the Charles Engelhard Court will discover airy display cases containing silver, ceramics, glass, pewter, and jewelry, newly arranged in a chronological sequence that underscores stylistic affinities. Beginning on the east side with colonial silver, the sequence continues onto the west balcony, where objects dating from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are installed alongside windows that afford a splendid view of Central Park.

| |

Fig. 2: Tiffany & Co. (1837–present), designed by Paulding Farnham (1859–1927), Adams vase, New York City, 1893–1895. Gold, amethysts, spessartites, tourmalines, freshwater pearls, quartzes, rock crystal, enamel. 19-7⁄16 x 13 x 9¼ inches; 352 oz. 18 dwt. (10977 g). Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Edward D. Adams, 1904 (04.1). |

The Met’s exceptional collection of domestic and presentation silver surveys the history of this precious metal in America. One masterful early example is the six-lobed bowl (Fig. 1) of 1700 –1710 marked by Cornelius Kierstede (1674 – ca. 1757), a New York silversmith of Dutch descent. This so-called brandywine bowl, ornamented with luxuriant flowers chased in repoussé, reflects the influence of Dutch design and customs in colonial New York. Following Dutch practice, it was used on ceremonial occasions such as the kindermaal, when neighborhood women gathered to welcome a newborn baby. Filled with raisins and brandy, it was circulated among the guests, who served themselves with a silver spoon.

In preparation for reinstallation, a number of the American Wing’s most important objects underwent careful study and conservation. One of those, the gold, enamel, and gem-set Adams vase (Fig. 2) is exhibited once again in all its splendor. Commissioned as a testimonial to Edward Dean Adams, when he retired as board chairman of the American Cotton Oil Company, the vase is modeled on the bell-shaped cotton flower, its rock crystal cover suggesting cotton bolls. Some eighty-five craftsmen contributed to this exquisite object, which was designed by Paulding Farnham (1859–1927), director of Tiffany & Company’s jewelry division. It was exhibited at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle and was presented in 1904 to The Metropolitan Museum. Set with approximately two hundred semiprecious American gemstones, the vase is one of the jewels of the American Wing’s holdings.

|

Fig. 3: Florence Koehler (1861–1944), pin, necklace, and comb, Chicago, ca. 1905. Gold, sapphire, emeralds, pearls, and enamel. Pin L. 2¾ in.; necklace L. 14 in.; comb W. 4¾ in. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Emily Crane Chadbourne, 1952 (52.43.1–.3). |

Two new balcony cases devoted entirely to American jewelry provide a rich overview of this field of artistic creation. Much of the earliest jewelry is small, personal, and of a sentimental nature, related either to death and mourning or to courtship and marriage. Later examples reveal the sophisticated artistry of American jewelers, such as the Arts and Crafts designer Florence Koehler (1861–1944), who made an outstanding suite of jewelry (Fig. 3) around 1905 for Emily Crane, daughter of the Chicago industrialist Richard T. Crane. Koehler’s interest in Renaissance sources is especially evident in the brooch, with its four rectangular emeralds and clusters of pearls framing an oval cabochon sapphire. A gem-set gold ring, originally part of this suite, has recently been acquired by the museum and is reunited with the other pieces for the first time in nearly sixty years. It is one of hundreds of examples of superb metalwork now on view in the new American Wing.

Beth Carver Wees is curator in the department of American Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

|

Marble Sculptures in the Charles Engelhard Court

by Thayer Tolles

| |

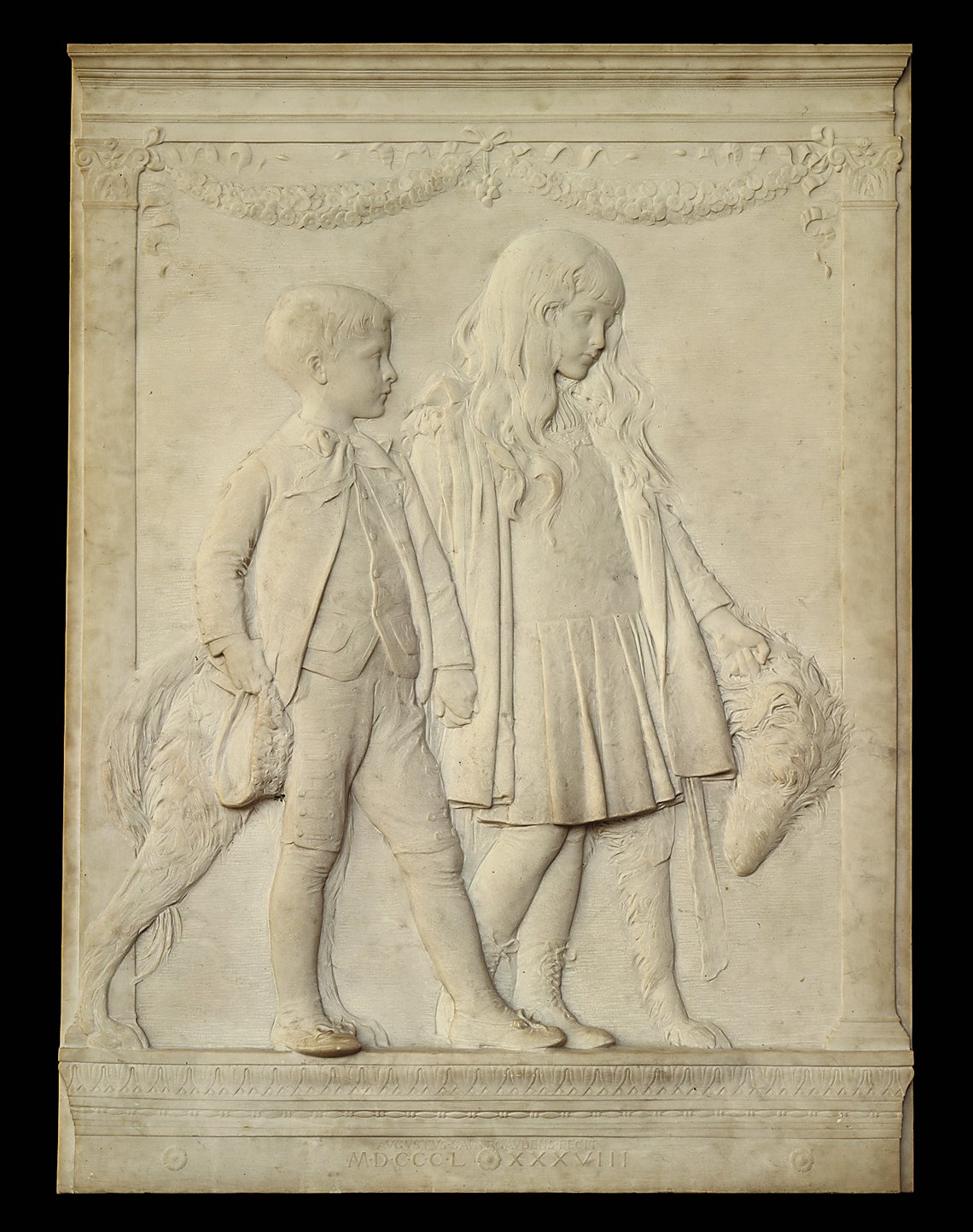

Fig. 1: Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), The Children of Jacob H. Schiff, modeled 1884–1885; carved, 1906–1907. Marble. H. 68⅞, W. 51 in. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Jacob H. Schiff, 1905 (05.15.3). |

For centuries, the abundant quarries of the Apuan Alps in Italy, especially at Carrara, have yielded fine-grained blocks of white marble that have been transformed into figurative statuary. American neoclassical sculptors who relocated to Florence and Rome in the mid-nineteenth century to be near these quarries relied on skilled Italian craftsmen to carve, drill, and polish this stone into ideal subjects and portrait busts from their intermediary plaster models. While these Americans developed international reputations, their loyal studio practiciens almost always remained anonymous. The newly installed Charles Engelhard Court features several examples of full-size marble groups completed abroad under these circumstances, including Hiram Powers’s California (1850–1855; carved 1858), which in 1872 became the first American sculpture to enter the collection.

By the late nineteenth century, bronze had surpassed marble as the preferred medium for the expressive Beaux-Arts aesthetic, but marble retained its symbolic hold as an ennobling, permanent material redolent with associations to a glorious classical past. In a reversal from previous carving practices that brought artists to the stone’s geographic source, hand-selected blocks of marble were shipped from Italy to the United States. American marble carving was dominated by the Piccirillis, six Italian brothers who immigrated and set up a flourishing studio practice, first in Manhattan, and after 1890, in the Bronx. They are responsible for the production of five marble sculptures in the Engelhard Court (Figs. 1-3).

When The Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned replicas of three bas-reliefs of children from Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907) in 1905, museum officials and the artist opted for marble despite the fact that bronze was the dominant material in his oeuvre. The Piccirillis completed The Children of Jacob H. Schiff (Fig. 1) shortly after the artist’s death, with finishing touches by his assistant Frances Grimes. Here the ability of marble to assume the texture of patterned fabric, curling hair, even wiry dog fur is expertly rendered in varying degrees of high and low relief.

|

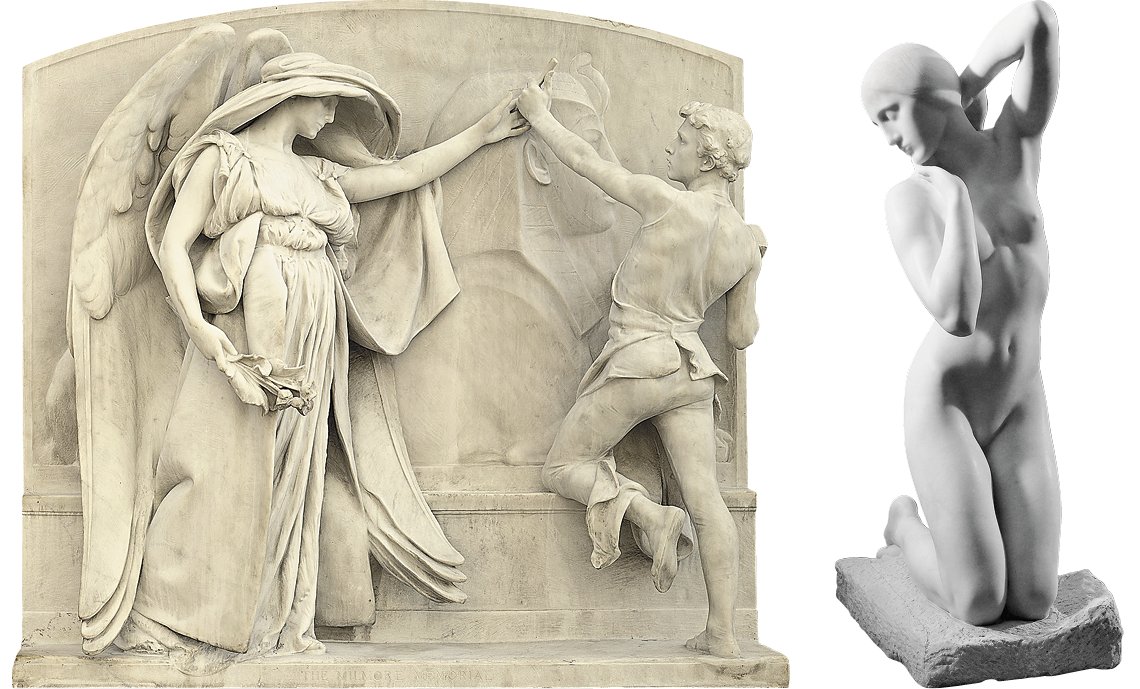

Left: Fig. 2: Daniel Chester French (1850–1931). The Angel of Death and the Sculptor from the Milmore Memorial, modeled 1889–1893; carved 1921–1926. H. 93½, W. 100½, D. 32½ in. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of a group of Museum trustees, 1926 (26.120). Right: Fig. 3: Attilio Piccirilli (1866–1945). Fragilina, modeled and carved 1923. Marble. H. 48½, W. 15½, D. 25 in. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Rogers Fund, 1926 (26.113). |

Daniel Chester French (1850–1931) had a longstanding relationship with the Piccirillis, who carved all his major sculptures after 1900; so when museum trustees commissioned marble replicas of his memorials from Massachusetts cemeteries, they again turned to the brothers. The Piccirillis first completed the heroic-scale Mourning Victory from the Melvin Memorial (1906–1908; carved 1912–1915), which in 1915 was installed at the top of the museum’s Great Hall stairs. Later, between 1921 and 1925, they carved The Angel of Death and the Sculptor from the Milmore Memorial (Fig. 2) from a block of Carrara marble, with French adding his own surface refinements. Poignant elements such as the poppies symbolizing eternal sleep and the angel’s intervening hand are accentuated in this technical tour-de-force. Today the Melvin and Milmore monuments share pride of place on the main level of the Engelhard Court, flanking Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Laurelton Hall loggia.

The Piccirilli brothers earned great respect for their carving skills, and several were also celebrated as independent sculptors. Attilio Piccirilli’s (1866–1945) Fragilina (Fig. 3) features an attenuated form and abstracted ovoid head that distinguishes his own ethereal style from that of his contemporaries. Purchased for the museum in 1926 at French’s recommendation, it is on display for the first time in the Engelhard Court, where visitors can now enjoy up-close, 360-degree access to the museum’s monumental marbles and appreciate the talents of the sculptors and carvers who collaborated to produce them.

Thayer Tolles is associate curator in the Department of American Paintings and Sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Early Summer 2009 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|