The Story of the Saturday Evening Girls

And Their Paul Revere Pottery

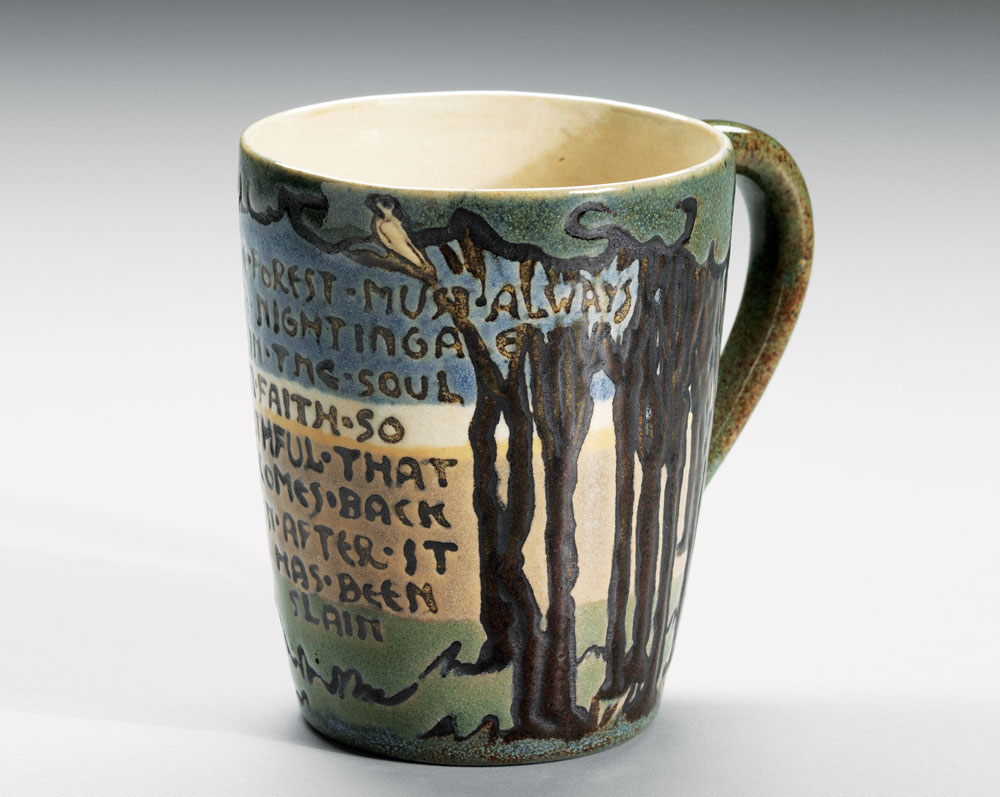

It is said that every object tells a story. A mug given to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, quite literally tells one (Fig. 1); inscribed on the side of the mug are the words: “In the forest must always be a nightingale & in the soul a faith so faithful that it comes back even after it has been slain.” A thicket of trees creating a dark canopy at the mug’s rim and a small bird, presumably a nightingale, perched on a branch illustrate the narrative. Where did this verse come from and why is it written on the side of this mug? Investigation into these questions reveals more stories; these broader narratives feature a young immigrant woman in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Boston and the reform efforts of the period that shaped her life and the lives of generations to come.

Inscriptions painted onto the base of the mug read: “S.E.G./12–14” and an “S.” surmounting a “G.” (Fig. 2). S.E.G. stands for the Saturday Evening Girls, a club for young immigrant women living in Boston’s North End at the turn of the twentieth century. The club was established in 1899 as a library reading club that met once a week under the guidance of librarian and reformer Edith Guerrier. Guerrier had been working for several years at the North Bennet Street Industrial School (NBSIS), a community charitable institution turned settlement house, when she was appointed the librarian of the North End branch of the Boston Public Library, located in the reading rooms of the NBSIS. Combining the missions of both organizations, Guerrier established a reading club to fill a void she saw in social and educational opportunities for girls. The group gathered on Saturday evenings for discussions of classic literature and for lectures by prominent Bostonians, soon adopting the name the Saturday Evening Girls (SEG).1

Attending the weekly meetings were the daughters of working-class Italian and Jewish immigrants living in the densely populated tenements of the North End. Their fathers were street peddlers, tailors, shopkeepers, and laborers, and their mothers worked in local sewing or dressmaking factories, or at home. The majority lived in crowded quarters, often sharing small apartments with extended family members and boarders.2

The “S.” and “G.” on the base of the mug are the initials of the mug’s maker, Sara Galner (Fig. 3). In 1901, at the age of six, Sara emigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the United States with her mother and younger sister Sophie to join her father and older siblings who had left two years earlier in search of economic opportunities and religious tolerance. The family eventually settled on Salem Street, a Jewish enclave in the North End. Sara’s father, Benjamin, worked as a butcher and her mother, Rebecca, stayed home to care for their six children and the household.3

Sara attended one of the local elementary schools, the Hancock School on Perameter Street. Through the public school curriculum, many students were introduced to the NBSIS, if they had not been familiar with its charitable mission already. A leader in educational reform, the NBSIS ran several joint programs with the local schools, offering vocational skills training for boys and girls. In 1885, the Hancock and Eliot elementary schools allowed students to take classes in “industrial education” at NBSIS during school hours; in 1891, when the Boston school board mandated manual training, the NBSIS expanded its program to fulfill those needs. These classes not only offered practical training, but had a secondary motive to “Americanize” children, promoting the children’s intellectual and moral capabilities and instilling in them a “patriotic” work ethic.4

The NBSIS also offered after-school activities for all ages. Sara Galner joined any class she could, as long as it was free. She took folk dancing, sewing, and cooking, and frequented the NBSIS girl’s reading room run by librarian Edith Guerrier.5 Few girls were encouraged by family members or the community to educate or even think for themselves, but Guerrier promoted their interest in books and ideas. Sara loved the reading room, despite her parent’s disapproval. Later in life, she said, she was “admired and criticized by my family” for her intellectual curiosity and desire to “improve” herself. She hid her books from her parents in her coat and read by the firelight after finishing her chores.

Guerrier recruited Sara and other girls for her SEG club from her reading room attendees. As its popularity increased, Guerrier expanded the library club into several groups based on age, each with its own curriculum meant to supplement school studies. In addition to core course work, the girls could explore folk dancing, dramatics, music, and other arts. The success of these groups, each named after the day of the week they met, attracted the attention of Helen Osborne Storrow, a noted Boston philanthropist who was particularly interested in the education and empowerment of girls. Storrow’s involvement with the library clubs was not limited to monetary donations; she spent time with the girls, leading folk dancing classes, and encouraging genteel behavior. Her dedication led her to build a summer camp, first in a small rented cottage in Plymouth, Massachusetts, before building a permanent camp in Wingaersheek Beach, West Gloucester, in 1906. The weeks in West Gloucester introduced Sara, and the other girls, to nature and rural life, a far cry from their lives in the North End.

Sara attended school through the age of fourteen, as required by law, graduating in 1908. Few immigrant families encouraged their daughters to pursue a high school education. However, Sara had impressed her teachers so much that school officials tried to persuade the Galners to allow Sara to continue her studies, even offering to pay the equivalent of what she would make working. Benjamin Galner refused the offer and Sara found a job working as a stock girl at R.H. White’s department store before securing a position as an assistant in a dressmaker’s shop on Boylston Street. There she procured fabrics, ribbons, buttons, and other supplies for her employer. Her eye for color and quality, in addition to a talent for negotiation, made her a favorite and trusted employee. And, despite her family’s disapproval, Sara enrolled at the Central Evening High School, no doubt inspired by her experiences with and support from her fellow SEGs. Records indicate that Sara took classes in English composition and German. Even with these many commitments—work during the day, school at night, and chores at home—Sara continued to be active in the SEGs and their various clubs.6

In 1907, Guerrier approached Storrow with the idea of establishing a retail pottery to give club members a way to earn their camp dues and additional funds. The philanthropist encouraged her to pursue the idea. With the help of her friend Edith Brown, an artist and illustrator, Guerrier began to develop a pottery business. Storrow purchased a building at 18 Hull Street in the North End to house the pottery and library clubs, and to provide an apartment for Guerrier and Brown on the top floor. Due to its proximity to the Old North Church, from whose steeple Paul Revere received his lantern signals before his famous ride, they named the enterprise the Paul Revere Pottery (PRP).7 The name also emphasized the American nature of the pottery’s wares, and by association, its workers (Fig. 4).

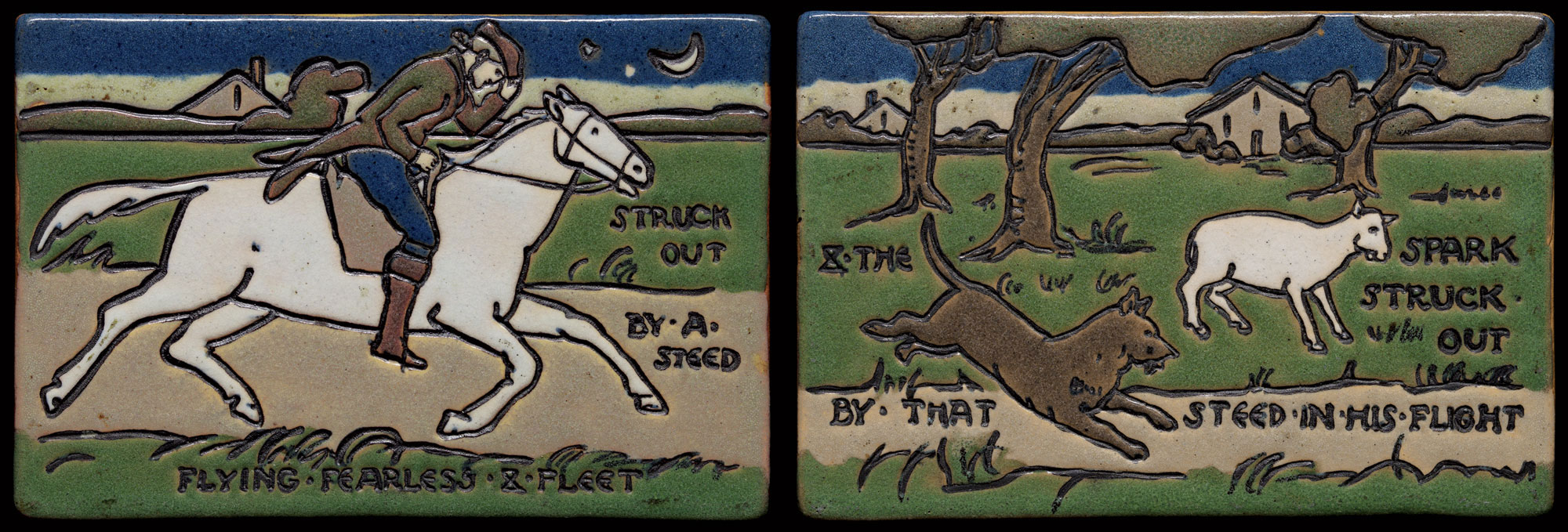

The new enterprise settled into its home in the basement of 18 Hull Street. An English-trained ceramicist, the only male in the organization, monitored the kiln. Club members took on the responsibilities of making and decorating the pots, caring for the workrooms, and staffing the Bowl Shop, a retail store on the first floor. Edith Brown, now the director and head designer of the PRP, developed the playful designs to decorate the wares. Drawing on her training at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and her experience as a children’s book illustrator, she produced stylized images of animals, birds, flora, and rustic scenes outlined with heavy black lines (Fig. 5). Her abstract style reveals her familiarity with the Arts and Crafts design reform movement and is similar to one of the movement’s leaders, English illustrator Walter Crane, among others.

Many Bostonians were intrigued by the reform ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, which was not only an aesthetic style, but a lifestyle philosophy that encouraged handcraftsmanship, the integration of art into everyday life, and healthy working conditions for artisans. They believed that creating art could improve a person both morally and spiritually.8 The Saturday Evening Girls Club and their Paul Revere Pottery are excellent examples of Arts and Crafts ideals in practice in America: poor, immigrant girls created beautiful pots by hand while working in clean workrooms for decent hours and decent pay. Each worker had flowers for inspiration at her station, volunteers would read classical literature, plays or newspapers, and each artist was allowed to sign her own work. A round, lidded box decorated with an abstracted lotus pattern is signed by both Sara Galner and her friend Fanny Levine, who must have collaborated on the piece (Fig. 6).

Sara Galner began her association with the pottery by decorating a few pots to pay her club dues. In about 1911 Edith Brown asked Sara to work full time, praising her quick and accurate work skills. Sara declined, claiming that she could not work for the pottery’s salary of four dollars per week, since she earned more at the dressmakers’ shop. Brown made a counteroffer and Sara successfully negotiated a salary of seven dollars per week, not only for herself, but for the other girls as well.

Already a proven businesswoman, Sara quickly stood out as one of the more talented decorators. Her steady hand, attention to detail, and sense of color are evident in the objects she produced. She worked on standard designs composed by Brown, such as the green or blue wares with a border of stylized trees, but regularly made them her own by lavishing more attention to the outline of the tree’s bushy crowns (Fig. 7). Sara also decorated special commissions, such as the simple bread and milk children’s sets that were among the pottery’s best selling wares (Fig. 8).

Sara’s expertise, however, was in floral designs. Her delicate and careful rendering of flowers, such as the irises on the covered beaker (Fig. 9) or the daffodils on the low vase (Fig. 10), suggests that she studied the plants in books, or perhaps from life. The “forest and nightingale” mug was made in December 1914, over three years after Sara joined the pottery full time. It is related to a set made by Edith Brown for Guerrier in December 1911, perhaps with Sara’s assistance. The verse comes from Chantecler, written in 1910 by French playwright Edmond Rostand. The play, whose characters are all barnyard animals, was performed in Boston to great fanfare in late 1911 through 1912. Perhaps Chantecler was read to the potters as they worked, painting images in Sara’s romantic mind that she translated into her pottery.

Sara Galner continued to work for the PRP, as a decorator and a sales clerk, until her marriage to Morris Bloom in 1921. Although the SEG club no longer met weekly after the start of U.S. involvement in World War I in 1917, and the pottery closed in 1942, Sara maintained her tight bonds with her fellow SEGs, especially the potters, until her death in 1982. Sara and Morris Bloom raised three children in whom the SEG values continue to thrive to this day.

More than 130 ceramic works decorated by Sara Galner were given to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, by Sara’s son, David L. Bloom and his family. Through this donation, made in the memory of his mother, Dr. Bloom and the museum hope to raise the artists of the Paul Revere Pottery out of anonymity. To celebrate this generous gift and to honor Sara Galner, the museum will display some fifty examples, including the forest and nightingale mug, in a special installation on view through March 2007. For information visit www.mfa.org or call 617.267.9300.

-----

Nonie Gadsden is the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Art of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This issue was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2 . Kate Clifford Larson, “These girls were quite ordinary. In their ordinariness, they proved extraordinary. The Saturday Evening Girls” (unpublished paper), 2001, 46–47.

3. Interview with David L. Bloom, son of Sara Galner Bloom, June 27, 2005; Passenger Manifest, The Zeeland, May 27, 1901, 240–241, The Statue of Liberty-Elis Island Foundation, Inc. available at www.ellisisland.com; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Decenial Census of the United States, 1910, Massachusetts, Suffolk County, Reels 615–616.

4. Kelly H. L’Ecuyer, “To Help Them Towards Industrial Salvation: Vocational Education at the North Bennett Street Industrial School” (unpublished paper), 2003, 8–20.

5. Video interview of Sara Galner Bloom by Barbara Kramer, 1976. Video courtesy of David L. Bloom. Source for all subsequent quotes and information about Sara Galner, unless otherwise indicated.

6. Interview with Betty Revis, daughter of Sara Galner Bloom, September 20, 2005; Boston Public Schools, Evening High and Trade School Student Records, 1909–1912, City of Boston Archives, Boston, reel 4.

7. Meg Chalmers and Judy Young, The Saturday Evening Girls: Paul Revere Pottery (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd.), 2006.

8. Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Thames and Hudson), 2004, 11.