Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings

|

Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings, was an exhibition at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento in celebration of the artist’s one hundredth birthday through one hundred works. Best known for his tantalizing paintings of desserts, Thiebaud has long been associated with Pop Art, though his range was far more expansive. Born November 15, 1920, in Mesa, Arizona, Thiebaud spent most of his childhood in Long Beach, California, and, for a time, southern Utah. He came to the Sacramento region of California with the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1942, having been stationed at Mather Field. Following his service, he worked in Los Angeles in the commercial art realm before deciding to pursue a career as a studio artist. In 1949, he enrolled at San José State College (today San José State University), taking both art and education courses. In 1950, he transferred to Sacramento State College (today California State University, Sacramento).

In 1960, Thiebaud started teaching at the University of California, Davis. Two years later, the Allan Stone Gallery in New York held a successful exhibition of his still lifes of food and commonplace objects, a watershed moment that launched his career. Not wanting to become pigeonholed as a still-life painter, Thiebaud subsequently focused on depicting people and landscapes. The latter came to include urban San Francisco views, and, subsequently, rural Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta scenes. All the while, he continued to explore the food subjects that made him famous. Based in observation and convincingly executed, Thiebaud’s art looks real and often feels comfortingly familiar, qualities that have made it beloved and led most viewers to describe it as “realist.” At the same time, extended looking evidences its unreality. Thiebaud filters his subjects through his memory, knowledge of art history, and imagination. Most of his finished works are manipulations of reality, capturing as much about what he knows or feels about a subject or place as its physical appearance.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), The Sea Rolls In, 1958. Oil on canvas, 36½ x 47 in. Crocker Art Museum Purchase, 1958.5. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

In 1957, after Thiebaud returned to California from a year-long teaching sabbatical in New York, he went to see the exhibition Contemporary Bay Area Figurative Painting at the Oakland Art Museum (now Oakland Museum of California). The groundbreaking show included paintings by David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn, and nine other artists who had moved beyond Abstract Expressionism to reengage with the visible world. Thiebaud made sketches of some of the paintings on view, which influenced his own abstract and representational work that followed—such as this seascape.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Pies, Pies, Pies, 1961. Oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of Philip L. Ehlert in memory of Dorothy Evelyn Ehlert, 1974.12. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Nearly everything Thiebaud depicts is either man-made, mass-produced, or somehow processed. In his still lifes, for which he is most famous, food is rarely straight from the garden, orchard, or farm but is, rather, manipulated and often laid out cafeteria-style, in orderly rows and display cases. He also tends to showcase a single type of food, such as pie or cake, a departure from the random assemblies of disparate objects so often depicted in the still lifes of art-historical tradition. “I’m interested in foods generally which have been fooled with ritualistically,” he explains, “displays contrived and arranged in certain ways to tempt us or to seduce us or to religiously transcend us.”

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Boston Cremes, 1962. Oil on canvas, 14 x 18 in. Crocker Art Museum Purchase, 1964.22. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Thiebaud’s food subjects represent the typical fare of snack counters, cafeterias, and diners across the United States. These works are also nostalgic, evoking personal memories for the artist. “It’s just very, very familiar,” he explained. “I spent time in food preparation, I sold papers on the streets, and I went into Kresses or Woolworths or Newberrys, to see the eccentric display of peppermint candy. They’re mostly painted from memory—from memories of bakeries and restaurants—any kind of window display . . . there’s a lot of yearning there.”

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book, 1965–1969. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wayne Thiebaud, 1969.21. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

After realizing critical and commercial success with his still-life paintings, Thiebaud decided to pursue new subject matter so as not to become associated with just one genre. He successfully applied for a grant from the University of California, Davis, that allowed him to take time off from teaching and paint figures. He pursued this endeavor over the course of the 1964–1965 academic year. At first he tried to work from memory, as he had in his still lifes, though the results were unsuccessful. He then turned to models, which helped him get the facts right. He started with friends and family, who would pose patiently and for free; he later hired models. Thiebaud’s wife, Betty Jean, posed frequently.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Pastel Scatter, 1972. Pastel on paper, 16 x 20⅛ in. Courtesy of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

In this work, Thiebaud created an exercise for himself: to draw pastels with pastels. Working from memory, he adjusted the pastels’ sizes and positions by intuition, considering the effect that they would have on the background and leftover empty spaces. He did not aim to accurately foreshorten or diminish the sizes of the pastels, opting instead to focus on the interplay among the pieces, “scattering” them in varying directions and rhythmic groupings that he punctuated with colorful fragments.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Street and Shadow, 1982–1983/1996. Oil on linen, 35¾ x 23¾ in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist’s family, 1996.3. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Street and Shadow is a cityscape, though the buildings and cars are less prominent than the asphalt roadways. As evidenced by the abundance of tire marks, the streets are clearly well traveled, yet there are no moving cars, just a few that are parked. At this quiet moment—likely very early in the morning, as the buildings cast long shadows—only a dog traverses the street.

|

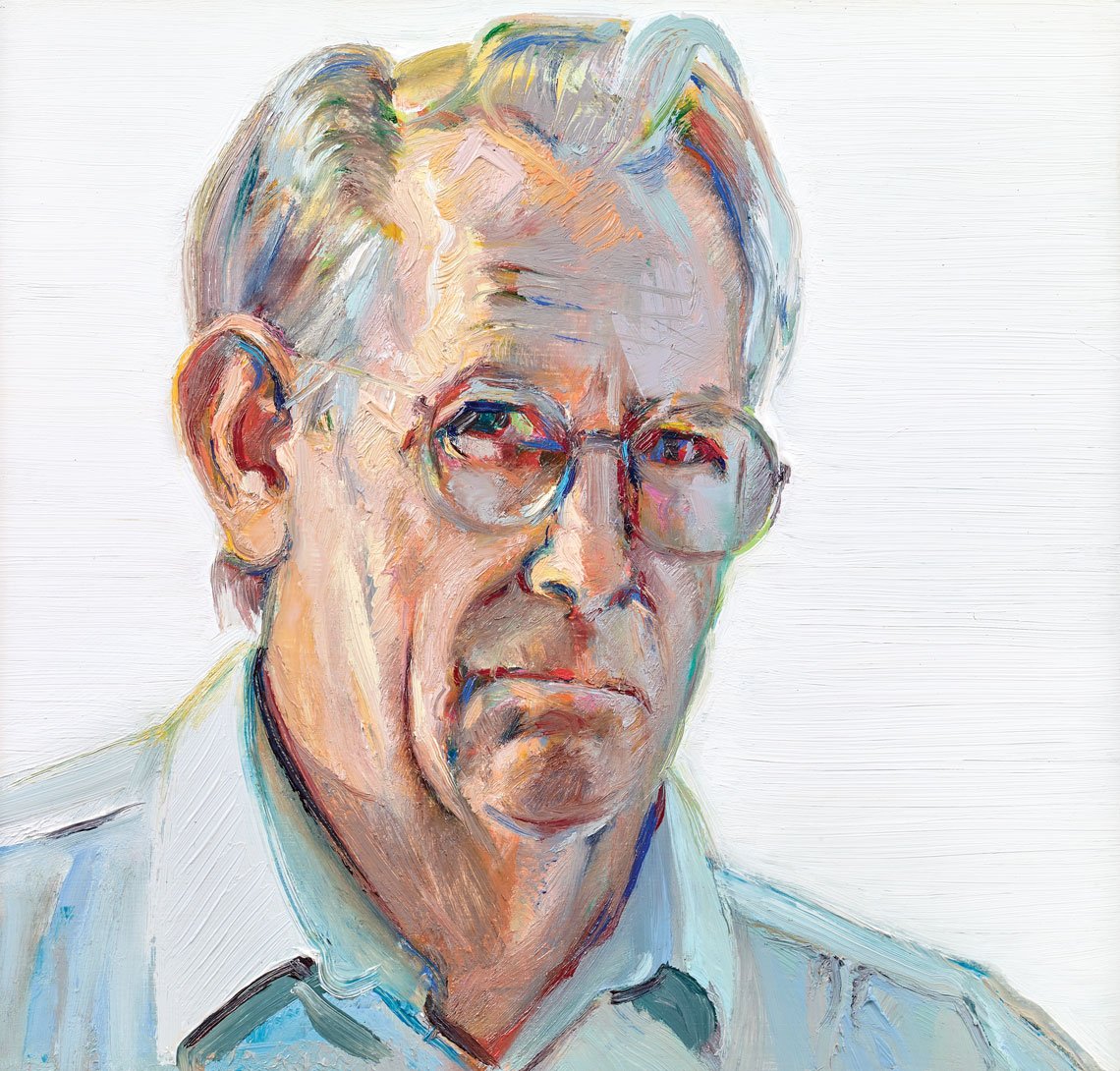

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Self-Portrait (4 Hour Study), 1989. Oil on board, 11½ x 12 in. Collection of Paul LeBaron Thiebaud Trust. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Thiebaud, like many artists, created multiple self-portraits over the course of his career. As indicated by the title, he produced this one in four hours. Thiebaud generally painted these portraits for his own edification, as they challenged his technical skills and served as a means of self-exploration, documenting how he changed over time.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Potrero Hill, 1989. Graphite on paper, 10⅜ x 8-11/16 in. Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist’s family, 1995.9.18.a. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Thiebaud began his series of street- and cityscapes in the early 1970s after he bought a second home in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood. He began his investigation of the steep terrain by painting more than twenty works from various intersections, hoping to capture the drama of the urban landscape. Initially, he had trouble obtaining the effects he desired, until an art critic advised him that artist Edward Hopper produced city views from a combination of sketches assembled back in the studio. Thiebaud consequently stopped painting and started drawing, creating hundreds of sketches that he would ultimately revise and reconstruct, combining what he could see with what he wanted to convey: a feeling or idea of the city that could affect viewers on a visceral level.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Cow Ridge, n.d. Etching hand-worked with colored pencil, 8-15⁄16 x 11⅞ in. (plate); 14-15⁄16 x 17-1⁄16 in. (sheet). Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist’s family, 1995.9.42. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Early in his career, Thiebaud worked as a cartoonist. Here, the steep, diagonal hill borrows from cartooning, as does the subtle humor of the narrative. Only two of the three animals in this hand-colored etching are cows. The third, following behind, is a bull. The latter, it seems, has amorous intentions, as he and the two females each have an abstracted heart on their hides.

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Valley Farm, 1993. Softground color etching and aquatint hand-worked with color pencil, 21½ x 15⅞ in. (plate); 27¼ x 19¾ in. (sheet). Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist’s family, 1995.9.51. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

Many of Thiebaud’s landscapes are almost entirely invented, drawing more from his imagination and memory than from nature. He also sought inspiration in non-traditional sources, such as George Herriman’s comic strip Krazy Kat, the antics of which were often set in a fantastical southwestern landscape. Thiebaud admitted that many of his own landscapes come out of Krazy Kat—“clouds, mesa, and things.” For Thiebaud, the introduction of humor and cartoon strategies into the long (and in California, especially, revered) tradition of landscape painting was one more way to breathe new life into an old subject. As Thiebaud put it, “Cartoons allow the silly to sit with the sublime.”

|

Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Park Place, 1995. Color etching hand-worked with watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, graphite, and pastel, 299⁄16 x 20¾ in. (sheet/image). Crocker Art Museum, gift of the artist’s family, 1995.9.50. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

By manipulating perspective and scale, deemphasizing some sections and inflating the importance of others, and combining three dimensional and flat passages, Thiebaud’s street- and cityscapes are blatantly unreal, even surreal, in scope and combination. And yet, at the same time, these scenes just manage to retain a sense of believability. Thiebaud stated, “That dialogue between what was actually there and what was made up became the basis of the entire series.”

|

| Wayne Thiebaud (1920–), Bumping Clowns, 2016. Oil on linen, 24 x 36 in. Peress Family Collection. © 2020 Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y. |

One of Thiebaud’s last series of paintings depicted circus clowns. This particular work also drew inspiration from his love of tennis, which, even as he neared 100, he still played. Twin brothers and professional tennis players Robert Charles “Bob” Bryan and Michael Carl “Mike” Bryan (known as the Bryan Brothers) are famous for their chest bump—an affectionate, fraternal gesture between doubles partners. The clowns in this painting mimic a similar but more comedic gesture as they bump noses.

He died on December 25, 2021, at the age of 101.

Organized by the Crocker Art Museum: Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings was shown at the following venues: Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, Calif.: until January 3, 2021; Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio: February 6–May 2, 2021; Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tenn.: July 25–October 3, 2021; McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Tex.: October 28, 2021–January 16, 2022; Brandywine Conservancy & Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, Pa.: February 5–May 8, 2022.

Scott A. Shields, Ph.D., is Associate Director and Chief Curator of the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, Calif.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.