Three Bucks in the Fontainebleu Forest

-

Description

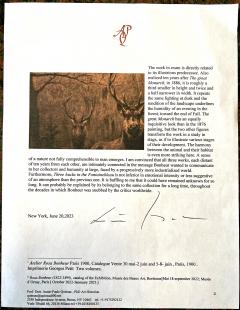

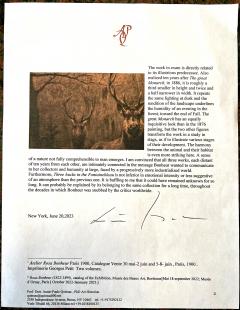

We are grateful to Annie-Paule Quinsac for confirming the authenticity of this painting.

Rosa Bonheur: Three Bucks in the Fontainbleau Forest, erroneously Stags or Monarchs in the forest

Oil on canvas, 29 x 24 inches [74 x 61cm], signed and dated lower left, Rosa Bonheur 1886

The discovery of this painting, a reinterpretation of Bonheur’s most iconic work Le roi de la Foret, [Monarch in the forest]is a significant event in the artist’s scholarship. In forty years of study, I was not aware of its existence and did not find any reproduction of it throughout my extensive reading. Bought by the present owner at the Stamford Winter Auction in 2008, it had been the property of a certain Captain [ name illegible] until January 29, 1920, or from that date {?}. The label on the back of the canvas reads: “Collection of Captain J.H.Gaucis Jan.29,1920”. [the handwriting on the label is extremely unusual; my deciphering of it induces me to propose this last name, Latvian in origin] […]

This work could not have been offered among the 95 paintings that compose the catalog section titled “Stags, Hinds, Roebucks,” [ NN.320-415] in the catalog of the Rosa Bonheur Posthumous Sale organized by the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, which included over two thousand pieces kept in the studio and not sold during her life time : it does not correspond to any of the description or measurements given in these catalog entries. The number 5527inscribed in red on the back of the canvas could refer to the painting having be handled by the Knoedler Galerie, Paris and New York, which after Bonheur’s death, that of Ernest Gambart (1814-1902and George Petit, (1856-1920) was instrumental in the continued diffusion of her work in the US, maintaining her prices that had crashed elsewhere in Europe.

Despite difficulties in tracing the provenance history, the attribution to Rosa Bonheur, cannot be denied. Stylistic and iconographic characters are typical of her expressive means in the late 80’s. Also, it cannot be questioned that the calligraphy of signature and date is hers.

The work depicts three male deers- or bucks- of different age, in a trail, deep in the forest at twilight, just after sunset toward the end of Fall. The two big ones, have stopped in their track, facing the beholder frontally; the small one, in profile, seems ready to move in another direction. The umbrella term deer, or the more specific one buck {male deer} could both be used as title to this painting, rather than stag, which implies an old majestic senior male deer, considered the King of the forest also called Monarch. In the Cervidae family, the number of points of a deer’s antler is one of the indicators of age, along with body mass and overall size. In our painting, the most prominent stag is massive and has a twelve points antler – qualifying as Monarch. The one immediately behind him exhibits an eight points antler and appears strong and imposing as well does not possess but not his companion’s poise. It is a mature stag. The last one, slender, shoulders not quite muscular yet, with barely six points to his antler, could not be more than two years old. The intensity of expression of the two older stags and their presence in the landscape which is rendered as their stage, are characteristic of Bonheur’s rapport to animals and nature.

The painting’s varnish has deteriorated and forms a film that will need to be removed through a cautious cleaning. It is particularly important that the transparent haze that evokes the humidity of the forest at that crucial moment of the light be preserved. It contributes to the painting vibrance.

Since 1860, when Rosa Bonheur moved to the Chateau of By, which she had bought with her companion Nathalie Micas, the Fontainebleau Forest which was at a stone through of her property, became ground of studies and the Cervidae a common subject. By then, she would already sketch en plein air, and months or years later, create paintings from start to finish in the studio using the visual material collected while walking through nature or observing animal in their milieu.

Her first image of the Great Monarch in the forest, represented frontally and in a similar forest background is the 1868 painting Le cerf de Saint Hubert [Hubertus’ Stag], an illustration of the legend of Saint Hubertus in which she included a cross between the stag’s antlers. As the story as it, Hubertus was a passionate hunter and would often forget his religious duties to go hunting. On a certain Sunday in the depth of a forest, where he had ventured alone, he began to pursue a stag The animal faced him and while a cross appeared between his antlers, the voice of God was heard, directing him to repent ad respect all animals. Rosa Bonheur was herself a hunter but also a spiritualist, influenced by the Saint Simonian creeds and by spiritism. She believed that certain animals had a soul. I personally think that magnificent monarchs and the St Hubertus’ legend had both a symbolical meaning for her.

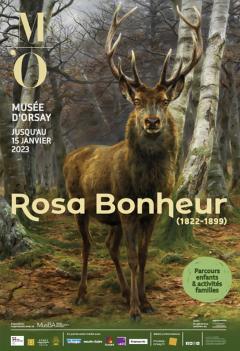

Ten years later, 1878, reusing the same setting, she produced one of her most iconic paintings, Le roi de la foret,( The great Monarch). While in the last thirty years of her life, she rarely sent pieces to international exhibitions, trusting her dealers to represent her in all venues, and having accumulated enough of a fortune to be totally independent from the fluctuations of the art market, she exhibited that work at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, indicating by this choice that she considered it one of her major life’s accomplishments. Ernest Gambart, the most sensitive of her dealers, chose the painting for one of the three bronze plaques to be inserted in the base of the monument which he donated to the town of Fontainebleau to be erected in her memory (1904). In this work too, a celestial light seems to be coming from the left of the composition. Very recently the painting was exhibited in occasion of the Retrospective Rosa Bonheur at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and illustrates the catalog cover.

The work in exam is directly related to its illustrious predecessor. Also realized ten years after The great Monarch, in 1886, it is roughly a third smaller in height and twice and a half narrower in width. It repeats the same lighting at dusk and the rendition of the landscape underlines the humidity of an evening in the forest, toward the end of Fall. The great Monarch has an equally inquisitive look than in the 1876 painting, but the two other figures transform the work in a study in stags, as if to illustrate various stages of their development. The harmony between the animal and their habitat is even more striking here. A sense of a nature not fully comprehensible to man emerges. I am convinced that all three works, each distant of ten years from each other, are intimately connected in the message Bonheur wanted to communicate to her collectors and humanity at large, faced by a progressively more industrialized world. Furthermore, Three bucks in the Fontainebleau is not inferior in emotional intensity or less suggestive of an atmosphere than the previous one. It is baffling to me that it could have remained unknown for so long. It can probably be explained by its belonging to the same collection for a long time, throughout the decades in which Bonheur was snubbed by the critics worldwide.

Dr. Annie-Paule Quinsac

New York, June 20,2023 -

More Information

Documentation: Certificate of Authenticity Origin: France Period: 19th Century Materials: oil on canvas Condition: Good. work has been relined but there is a heavy layer of demar varnish that is making the work dark. Varnish should be removed and work will will sing with detail Creation Date: 1886 Styles / Movements: Realism, Barbizon/Tonalism Incollect Reference #: 169683 -

Dimensions

W. 24 in; H. 29 in; W. 60.96 cm; H. 73.66 cm;

Message from Seller:

You'll find an eclectic group of art works at Robert Funk Fine Art. 45 years of experience has shaped Director Robert Funk's multi-perspective approach to presenting art. As an undergrad in painting, he studied with great teachers such as first-generation abstract expressionist Robert Richenburg and hyper-realist painter Janet Fish. In Graduate School he worked with famed critic E.C. Goossen and went on to work as a Photographer, New York Advertising Art Director, and Art Collector.