Fairy Tale in Technicolor: The Photography of Mark Shaw

|

|

In this 1955 photograph from Mark Shaw (1921–1969), top right, a model with alabaster skin reclines against a bed of ivy. She is wearing a Dior dress embroidered with gold—and ruby lipstick to match.

-

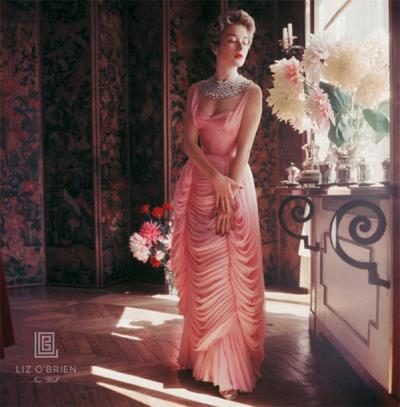

Mark Shaw, Courtyard Chanel Red Velvet, 1955/2017. From Liz O’Brien (New York).

This photograph, now being offered by Liz O’Brien (New York) in conjunction with the Mark Shaw Photographic Archive, was originally taken for a cover story in the September 5, 1955 issue of LIFE magazine, the preeminent publication dedicated to American public life at the time. In the text that accompanies the photo shoot, the writer opines, “For fashion professionals at the fall collections, it seemed like the old Paris. The French designers were not attempting to enforce new shapes [but] were presenting a big showcase of beautiful and splendid clothes. These pictures give Americans a first chance to see in color the gay, rich and varied new Paris fashions.”

In effect, Shaw had staged a fairy tale in Technicolor, assembling a cast of immaculately-dressed models to gambol in the streets of the Marais. “He was teasing an American audience, giving them a little taste of how aristocrats lived,” says Juliet Cuming, director of the Mark Show Photographic Archive in East Dummerston, Vt., and wife of David Shaw, the artist’s only child. “His whole schtick was not just showing the beautiful clothes, but showing the beautiful clothes on location and really putting all of this stuff into context. He was selling Americans the idea of Europe as this beautiful, historical, classy place.”

The collection of photographs on offer at Liz O’Brien sheds new light on the artist’s creative process, presenting images that never made it to publication, such as “Red and White Satin Balenciaga Gown in Paris Courtyard”, or “Courtyard Chanel Red Velvet.” Many of these outtakes were too inventive to appear in the pages of LIFE, which was known for running anodyne photographs “that were so conventional that they pleased almost no one,” says Cuming. “Some historians have pointed to Mark as one of the first modern photographers. Before him, it was a formal, stiff medium. His photographs have a more candid, relaxed feel. It probably seemed a little strange at the time for him to take these photos, but now it totally works.”

-

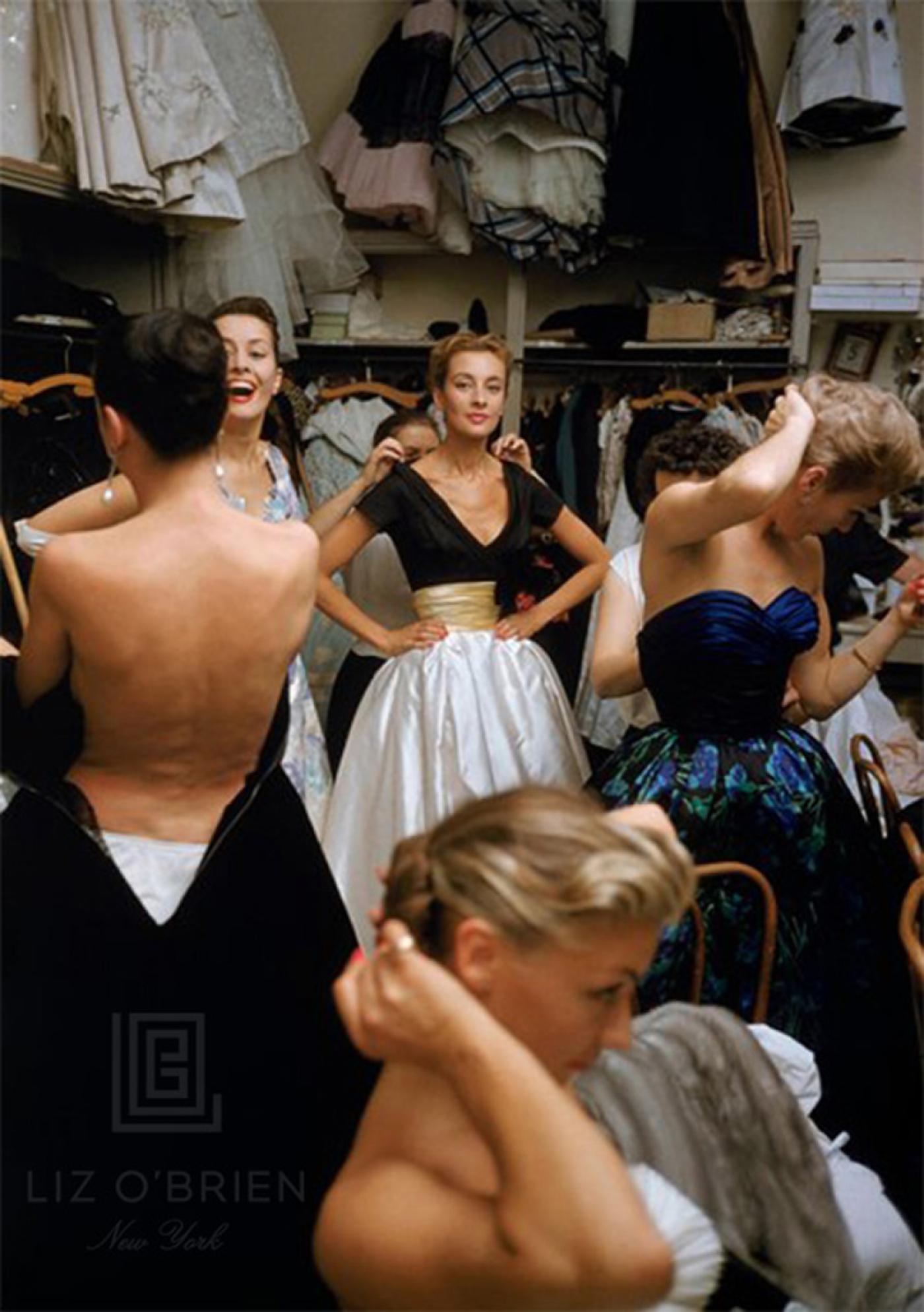

Mark Shaw, Backstage Balmain Blue Train, 1954/2017. From Liz O’Brien (New York).

-

-

Mark Shaw, Backstage Balmain Black Top, 1954/2017. From Liz O’Brien (New York).

Apart from his photographs of Chanel-clad waifs in the city’s medieval quarter, Shaw took numerous shots of models in a state of undress backstage at a 1954 Pierre Balmain show. It is tempting to view these photographs as a behind-the-scenes look at the construction of spectacle, not unlike Edgar Degas’ paintings of ballerinas from a privileged vantage point backstage. But, unlike Degas, who set out to chronicle modern life in late-nineteenth-century France, Shaw almost certainly knew that his backstage photos were too risqué to be viewed by the public.

“We can’t forget, this was the early 60s,” says Liz O’Brien, who was introduced to David Shaw through a mutual friend and was drawn to the artist’s work by his shots of fashionable dress in the context of lavish interiors. “Even ten years ago, photographs of girls getting changed would have been considered a little racy. But, for him to do this at that time was very forward-looking.”

Born Mark Schlossman, the artist was raised in humble circumstances in a working-class New York City household. He was often sick as a child but exhibited an aptitude for photography at an early age. “There are different stories about how Mark Shaw got his camera,” says Cuming. “One story that has circulated is that he was so ill as a child that he was given a camera to entertain him because he could not go out and play with the other kids.”

Shaw enrolled in college with the intention of becoming an engineer and later served as a pilot in World War II, taking reconnaissance photographs from the cockpit. On his return home, he began taking photographs for Harper’s Bazaar under the tutelage of Alexey Brodovitch and swiftly ascended to the top echelon of American fashion photographers. “He had the ability to get along with a very wide range of people, and that was the key to his success,” says Cuming. “He could banter as easily with the seamstresses as with their most high-profile clients. He was everybody’s friend.”

Shaw is best known to the general public as the chronicler of Camelot, taking shots of Jacqueline and John F. Kennedy on behalf of LIFE. Following his death in 1969, much of his work was put into storage, where it remained for forty years. The prints now available at Liz O’Brien are made to order in limited editions on Hahnemϋhle photo rag paper. Each print is accompanied by a letter of authenticity and signed and numbered by David Shaw.

To see more work by Mark Shaw, please click here.